Caroline’s Clothes: The Life and Loss of an Antebellum Woman

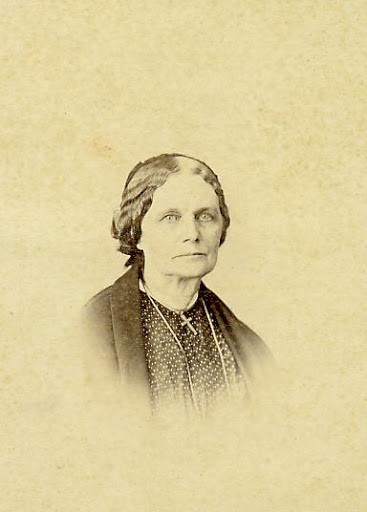

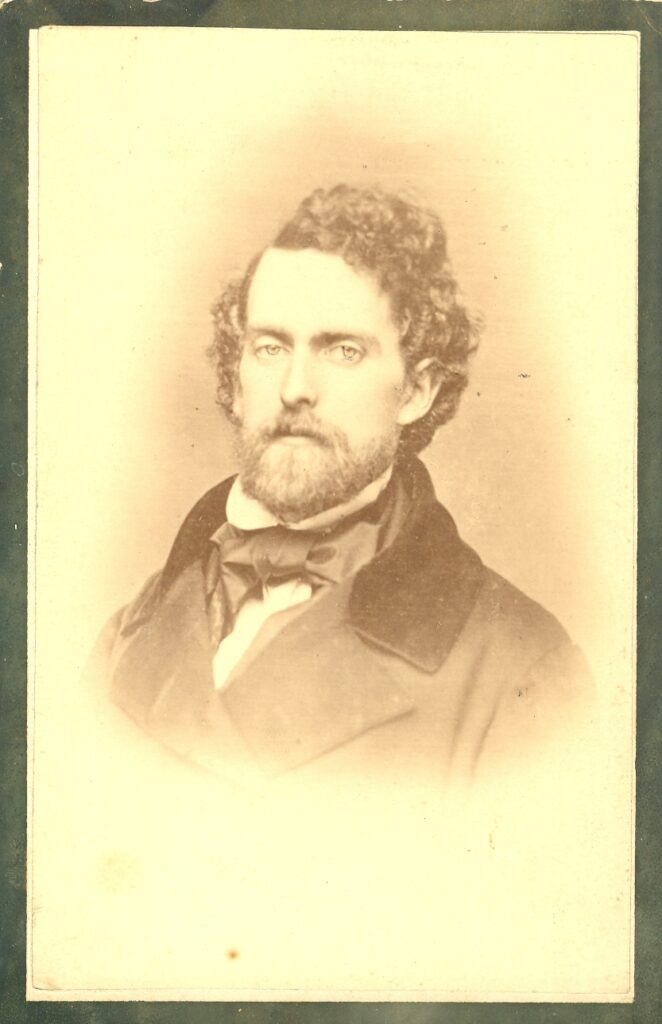

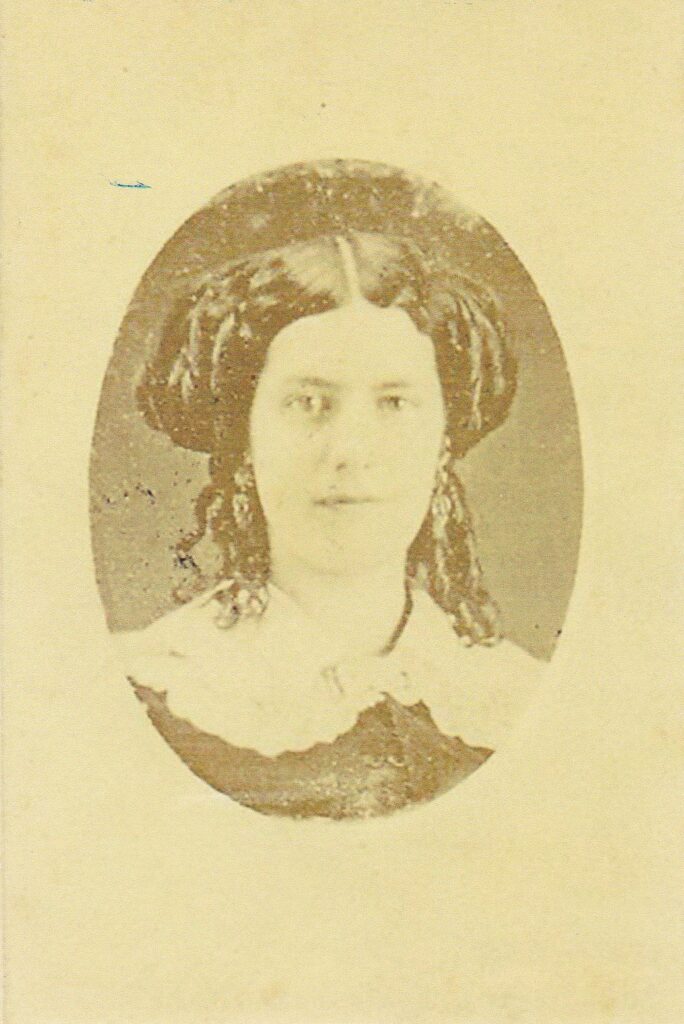

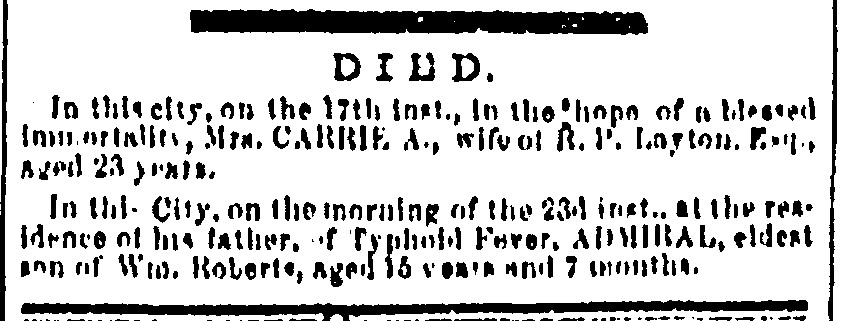

In Chatham Center, New York, it is said that the ghost of Caroline Sutherland Layton, a beautiful young woman who died in the 1850s, can sometimes be seen in her wedding dress walking the fields and picking flowers near her childhood home.

Caroline’s wedding gown happens to be in the historic textile collections of the Illinois State Museum, and her ghost tale was the first thing I learned while researching its provenance for an upcoming exhibition. It wouldn’t be the last. Caroline’s story, teased out of her artifacts and a few fleeting written references, represents a powerful, if brief, window into the life of a woman whose trajectory was all too common in her time: someone who married, moved west, and died young. In Caroline’s case, all of this happened within twelve months.

Analyzing these garments and the scant historical record against the backdrop of her social and historical context produces a poignant view of a westward migrant. It shows how she invested emotional, social, and physical work in building a life and family in a new state. Like many young brides who went west with their husbands, Caroline gambled the comfort of the familiar on the promise of the new. And like many young brides, Caroline lost that gamble, dying young despite her advantages of class and wealth.

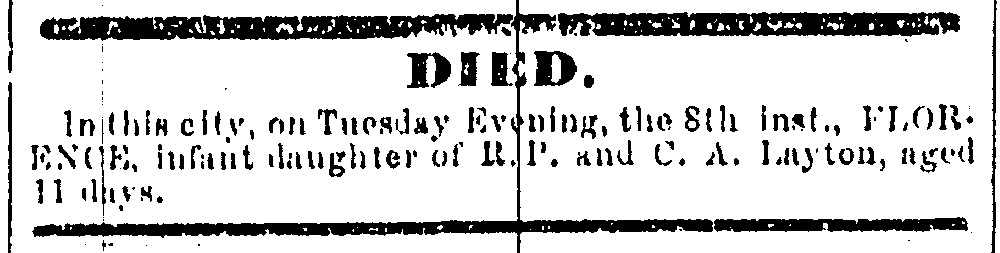

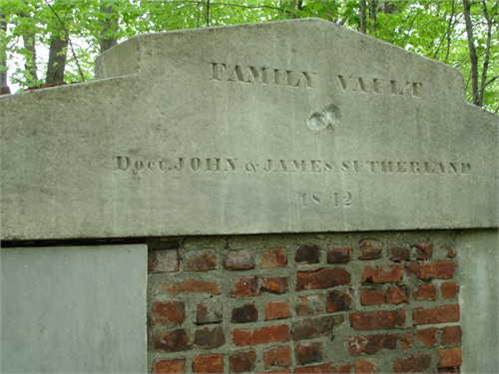

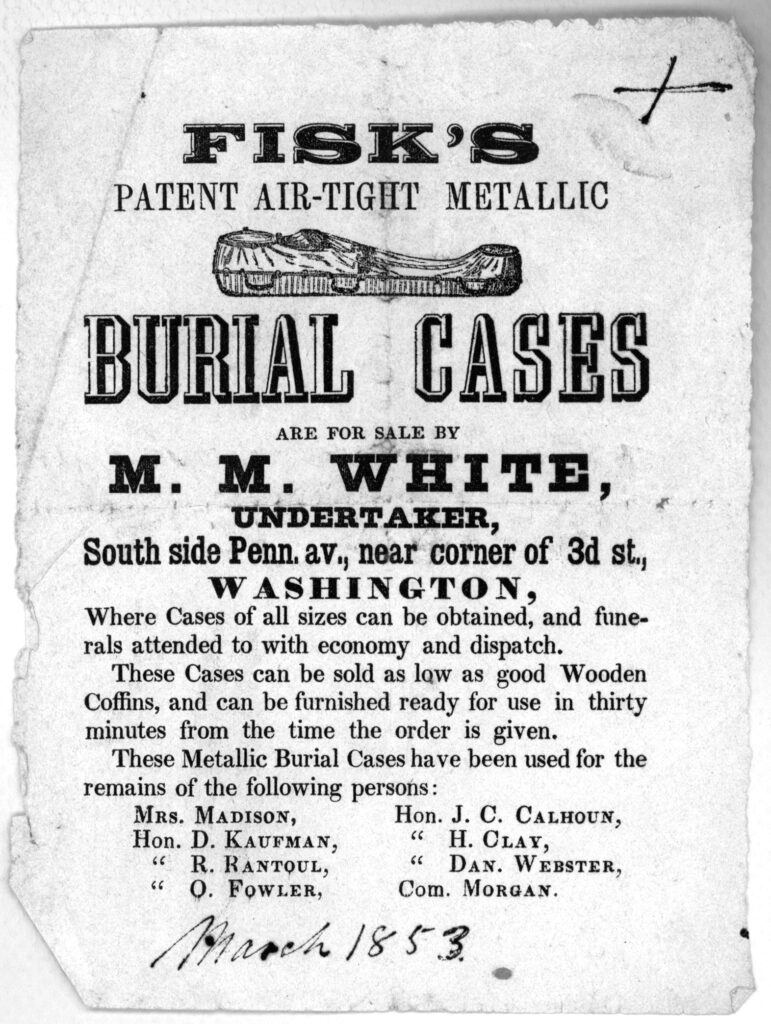

Like countless other women, Caroline is remembered only as a brief footnote in the historical record. No family letters by, to, or about her survive. She appears only in the 1850 federal census, an 1851 school catalog, and three newspaper tidbits between 1856 and 1857. Beyond that, she is remembered only as a ghost story, and because of a macabre postscript to her life: in the 1930s, her family vault crumbled, and curious trespassers found Caroline’s iron coffin within. Visible through a glass faceplate, Caroline’s body was in a remarkable state of preservation, appearing unchanged by time. Word quickly spread through town, and scores of locals hiked out to the burial vault to gaze at her features. A newspaper article called her the “vision in the vault,” and the story of her extraordinary postmortem appearance passed into local legend.

Fortunately, something more tangible than a legend remains of Caroline. A small collection of her personal garments was preserved by her family for more than a century and a half. Initially sent back to New York with her remains after her death, they were brought to McLean County, Illinois, with her mother and brother when they relocated there in the late 1850s. They passed down through generations of her brother’s descendants until 2019, when they were donated to the Illinois State Museum.