Civil Unions in the City on a Hill: The real legacy of “Boston Judges”

In his recent call for a constitutional amendment banning homosexual marriage, President Bush declared to the American people that “the union of a man and woman is the most enduring human institution, . . . honored and encouraged in all cultures and by every religious faith.” He warned that “marriage cannot be severed from its cultural, religious and natural roots” without dire social consequences, and he placed much of the blame for the current threat on “activist judges.” Without a constitutional amendment, “every state would be forced to recognize any relationship that judges in Boston . . . choose to call a marriage.” The president’s supporters have echoed his sentiments in countless op-ed pieces and letters to the editor, upholding the sanctity of marriage and its unchanging traditions in the face of challenges by gay-marriage advocates.

The outcry against gay marriage rests on the assumption that marriage is a “natural” institution rooted in timeless religious and cultural practices. But President Bush and his supporters have got their history wrong, at least with respect to religion, government, and marriage in Massachusetts. The Puritan colonists who founded Massachusetts might not have welcomed same-sex households, but they were not afraid to use the power of government to redefine marriage. And they surely would have agreed with today’s gay-marriage advocates that the state and its concern for fairness, not the church and its concern for sanctity, should govern the social rules for joining two people in perpetual union.

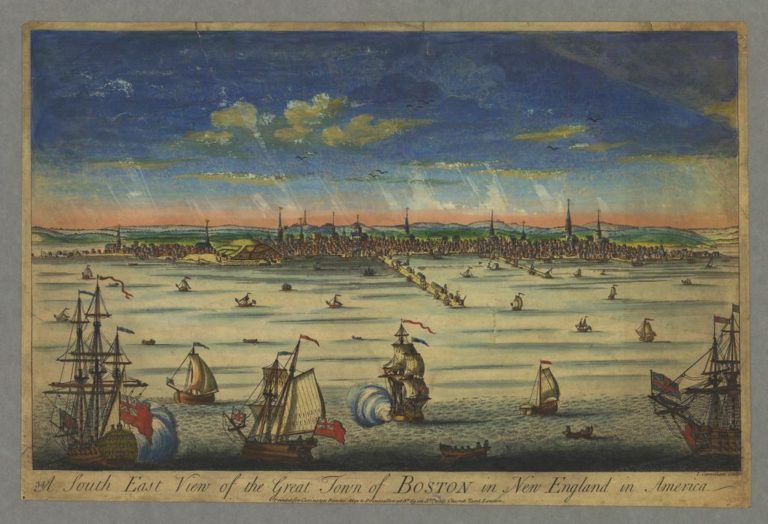

The English Puritans who founded Massachusetts in 1630 formed a society as committed to religion as any in history. But for them, marriage was a civil union, a contract, not a sacred rite. In early Massachusetts, weddings were performed by civil magistrates rather than clergymen. They took place in private homes, not in church buildings. No one wore white or walked down the aisle. Even later, when it became customary for ministers to preside at weddings (still held in private homes), the clergy’s authority was granted by the state, not the church.

Massachusetts’ founders insisted on civil unions, not as a reluctant compromise with the state, but as a direct outgrowth of their religious beliefs. Puritans were dissenters from the Church of England, which like the Catholic Church treated marriage as a sacrament. In England, the king was “defender of the faith,” bishops sat in the House of Lords, and the Church of England had legal authority over all religious matters, including marriage. Puritans strongly opposed this system. They wanted to adhere strictly to the Bible in shaping their forms of worship, but as they read it, the New Testament offered no precedent for bishops, ecclesiastical courts, and royal control over religion. What’s more, they held that the Bible sanctioned only baptism and communion as sacraments, since these were the only sacraments that Jesus took part in himself.

Marriage remained important to Puritans (it was often used as a metaphor for the divine love between believers and God), but they wanted to remove it from the realm of sacred authority, leaving only the sacraments under church control. This radical change was impossible to achieve in England, where the unified church and state used its power to persecute dissenters. But when they migrated to Massachusetts, the Puritan founders were free to shape their new society according to their beliefs. As a result, Massachusetts had no bishops, no ecclesiastical courts. The state regulated all aspects of the marriage process, from “publishing the banns”–an announcement of the intent to marry that was an early predecessor to the marriage license–to the marriage ceremony, the giving of dowries, property and inheritance rights, and in rare cases, divorce.

Early Boston’s Puritans would not have sanctioned gay marriage, because they would not have had the conceptual categories to make sense of the idea. They condemned and occasionally punished homosexual behavior as a sin, a deviation from the procreative function of sexuality. But in this light, homosexual behavior was not categorically different in their eyes from other forms of sexual transgression, from premarital sex to masturbation. Sexual behavior was something a person did, an action of the moment, not a form of identity or a defining characteristic of a person’s nature. Race, by contrast, was a category that New England’s Puritans often did regard as a form of identity, a defining characteristic that separated Europeans from Africans or Native Americans. In this respect, they were no different from most people of that era. And yet Puritans like Samuel Sewall, a judge on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and author of the first antislavery pamphlet in America, abhorred the laws barring interracial marriage. He fought to grant legal recognition to the marriages of slaves and free people of color. Sewall stands at the beginning of a proud tradition in which Massachusetts judges used the court’s power to decide cases in favor of equal rights for all. In Sewall’s view, all people “are the Sons and Daughters of the First Adam, the Brethren and Sisters of the Last Adam, and the Offspring of God; They ought to be treated with a Respect agreeable.”

Massachusetts history reminds us that what we commonly call marriage today was initially, and quite deliberately, constructed as a form of civil union. Although marriage was a fundamental aspect of these highly religious people’s lives and the foundational element of their social order, its regulation was separate from the church. The Puritan founders understood marriage as a social institution that needed adjustment according to changing circumstances, and they left the state to do this important work.

In every region of colonial North America, devout believers fought over how to define true religion, and where to draw the line between church and state. In some of the smaller and initially more homogeneous colonies like Massachusetts and Connecticut, religious uniformity was enforced by the state. But taken collectively, no single religion in colonial America ever had the power to decide for everyone, everywhere, what was sacred. As a practical matter, the traditional practice of state-enforced religious uniformity proved to be unworkable in the new American republic. It was this de facto diversity that the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution enshrined in federal law.

Different religious communities have long maintained different standards governing who can marry, whether interfaith marriages are permissible, what the obligations of marriage entail, and when or if divorces can be granted. We should not forget that the English Reformation began in 1529 with a conflict between Henry VIII and Pope Clement VII over whether Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon could be annulled. Henry said yes, Clement said no, and in that dispute a new religious tradition, with new ways of defining the relationship between church and state, was born. The idea of legalized homosexual marriage is no doubt innovative. Some religious traditions reject it, while others support it. But the same was true of past adjustments to the legal definition of marriage, such as the recognition of interracial marriage. The traditions pioneered by Boston judges–a legacy that removed marriage from church control–have made these legal adjustments to social changes possible. A policy wherein all marriages are considered as civil unions would be consistent with America’s strongest traditions regarding civil liberties, equal rights, the separation of church and state, and the freedom of religion.

Further Reading:

On the history of marriage in the North American colonies and the United States, see Nancy F. Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation (Cambridge, 2000); Richard Godbeer, Sexual Revolution in Early America (Baltimore, 2002); Ann Marie Plane, Colonial Intimacies: Indian Marriage in Early New England (Ithaca, 2000); Roger S. Thompson, Sex in Middlesex: Popular Mores in a Massachusetts County, 1649-1699 (Amherst, 1986); and the Amici Curiae Brief of the Professors of the History of Marriage, Families, and the Law, filed in the case of Goodridge v. Dept. of Public Health, 798 N.E. 2d 941 (2003).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.3 (April, 2004).

Mark Peterson, who teaches history at the University of Iowa, is at work on a book about the history of Boston in the Atlantic World.