Civil War Veterans and the Limits of Reconciliation

By the summer of 1881, news of the recently discovered Luray Caverns in Virginia’s famed Shenandoah Valley had spread throughout the East Coast. Hundreds of curious visitors read accounts of the spectacular grottoes and began to flood the small farming town to see what was being touted as one of the world’s geological wonders. The Union veterans of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, were no exception—but theirs was not to be a sightseeing adventure alone. In June, the Carlisle post of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) wrote to the prominent men of Luray proposing an excursion of the ladies and gentlemen of Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley to the caverns. They suggested “a friendly exchange of greetings” with “yourself and other surviving members of the Confederate army.” There was no need for “ostentatious show” or “expensive reception.” Rather, they merely desired a “friendly hand-shaking.” “We will furnish a band of music,” the GAR post gladly wrote. “If you think favorably of meeting us there, with as many comrades as you can conveniently muster, we should be pleased to form the new acquaintances.”

On July 21, nearly 2,000 people, most of them Confederate veterans from the Shenandoah Valley, gathered at the newly opened Luray train station to greet 600 Pennsylvanians—their former enemies. Lieutenant Andrew Broaddus, Confederate veteran and editor of the local paper, delivered an address calling upon the veterans of both sides to forget the war, reminding them “that only cowards bear malice, and that brave men forgive.” He ardently believed that partisan leaders continued to employ political issues to “keep down the cry of peace that comes from every section,” but hoped that this meeting would do much to end such sectional animosities. In language that would prove representative of Blue-Gray reunions for decades to come, GAR Post Commander Judge R. M. Henderson concurred with Broaddus, but added that the veterans should “forget everything except the lessons of the past.” Veterans might gather on the former fields of battle to ceremoniously shake hands over the proverbial bloody chasm, but as Henderson observed, they would not surrender their cause.

Rather than fostering a memory of the war that erased the causes and consequences of the conflict, Blue-Gray “love fests” often created a deeper attachment to the respective Union and Lost Causes.

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, such affairs helped convince Americans on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line that the horrors of war and the upheavals of Reconstruction were behind them. The creation of the first national military parks, popular magazines, plays, and even political campaigns encouraged northerners and southerners to embrace their former foes in the spirit of brotherly love and American progress. In recent years, historians such as David Blight, Nina Silber, and Timothy Smith have interpreted these gestures as evidence of a new national memory of reconciliation that triumphed over earlier memories of the war. Forgotten was the Union Cause with its emphasis on preserving the republic and ending slavery, they argue. Buried were the disputes over the war’s causation. Instead, northerners appeared to buy into the Lost Cause sentiments that extolled the battlefield bravery and valor of all (white) soldiers. Reconciliation, these scholars contend, offered both a white-washed memory of the war and a vision of sectional healing on Confederate terms.

This vision of sectional harmony premised on amnesia about the war’s causes, however, was not shared by most veterans. Instead, the majority adamantly defended their own cause as righteous and just while refuting that of their opponent as without merit. Rather than fostering a memory of the war that erased the causes and consequences of the conflict, Blue-Gray “love fests” often created a deeper attachment to the respective Union and Lost Causes. While they might occasionally meet in the spirit of reconciliation as they did at Luray in 1881, neither Union nor Confederate veterans were willing to forget—much less forgive—all that had happened. True, heart-felt feelings of reconciliation were rare indeed.

To understand the role of Reconciliationist sentiment in shaping the memory of the Civil War, it is helpful to recognize the various memory traditions of the conflict. The Lost Cause, a romanticized interpretation of the war in which Confederate defeat was presented in the best possible terms, emerged even before the soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia had stacked their weapons and signed paroles. On April 10, 1865, Robert E. Lee read his General Order No. 9 to his men at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. In it, he lauded the loyalty, valor, and “unsurpassed courage and fortitude” of “the brave survivors of so many hard-fought battles” and assured his men that the surrender was through no fault of their own. Instead he insisted that the army had been “compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.” By the 1870s, through the efforts of elite white southern women of the Ladies’ Memorial Associations who helped establish Confederate cemeteries and the first Memorial Days, as well as such former Confederate leaders as Jubal A. Early, most white southerners had embraced the Lost Cause. Defenders of this version of the war’s history repeatedly maintained that states’ rights, not slavery, had caused the conflict and held that most slaves remained faithful to their masters even after emancipation. They claimed that Confederate soldiers had fought honorably and bravely and that the South had not been defeated but overwhelmed by insurmountable odds (and therefore was destined to lose). They maintained that, throughout the war, southern white women remained loyal and devoted to the cause. Finally, they heralded Robert E. Lee as the epitome of a southern gentleman and the greatest military leader of the war.

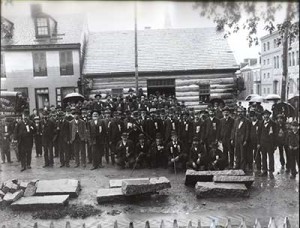

White northerners likewise began to memorialize their cause in the postwar period. But instead of women, the Union army performed the burials while veterans’ organizations, such as the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), orchestrated Memorial Days. As former Confederates sought to explain their defeat, the triumphant North needed to elaborate on what victory meant for the nation. Most northerners celebrated the Union Cause, which argued that the war had been fought to preserve the republic from secessionist fanatics who threatened the Founding Fathers’ vision, and therefore, the future viability of democracy. Many of those who espoused the Union Cause included emancipation of the slaves within the accomplishments of victory, but others, such as Frederick Douglass, believed that emancipation was the most important cause and accomplishment of the war, and as such, espoused an Emancipationist memory.

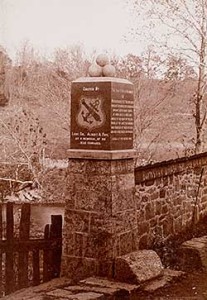

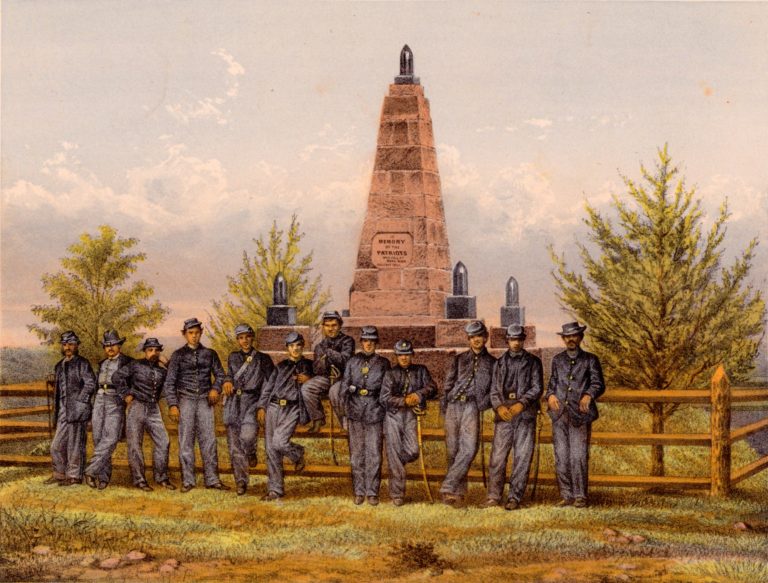

By the early 1870s, these were the three clear memories of the war: the Lost Cause, Union Cause, and Emancipationist Cause. After federal troops withdrew from the South in 1877, a fourth memory of the war appeared: Reconciliation. In the 1880s and 1890s, a heightened spirit of national reconciliation peaked in the United States. Union and Confederate veterans commenced participating in joint Blue-Gray reunions, while popular magazines such as The Century increasingly valorized the battles and leaders of the war. In the 1890s, extolling the bravery of former foes would reach its zenith at the first national military parks—Chickamauga and Chattanooga, Gettysburg, Antietam, Shiloh, and Vicksburg—created through the joint efforts of Union and Confederate veterans. But when the two groups met at Blue-Gray reunions, they agreed to remain silent on the divisive political issues that had caused the conflict as well as the turmoil of Reconstruction. Instead they commiserated about the severity of camp life and marches while commending each other for their bravery on the field of battle. For Reconciliation to flourish, white northerners and southerners had to reach a compromise predicated upon the exaltation of military experience and the insistence that the causes of the war as well as the postwar consequences, namely Reconstruction, be ignored.

But this reverence for Reconciliation was never complete, nor was it without qualifications. Union veterans continued not only to espouse their allegiance to the Union Cause (and in many cases, emancipation) at monument dedications and Memorial Days, they also maintained that theirs was the only good and noble cause. In southern periodicals and at Confederate reunions, former rebels persisted in their tributes to the Lost Cause. The Blue-Gray reunions and Reconciliationist rhetoric did not mean that animosity between the former foes had vanished. Instead, sectional animosity continued to linger, a fact made evident in the former Confederate capitol in the mid-1890s, during the so-called heyday of Reconciliationist sentiment.

On May 30, 1894, tens of thousands of former Confederates gathered in Richmond for the unveiling of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on Libby Hill. It was not the monument itself that would cause so much friction; rather, it was the words of the day’s orator, Rev. R. C. Cave, that sparked a national debate and stirred the embers of sectional animosity, violating the unspoken truce of Reconciliation. In the course of his address, Cave spoke the standard lines about soldiers’ bravery and devotion common at every monument dedication, be it Union or Confederate. But he went further that day, delivering what many northern writers described as a eulogy for the Confederacy. Appomattox had not been a divine verdict against the South, he argued; instead it had been the triumph of the physically strong. Going beyond the traditional Lost Cause message of overwhelming northern resources, he intoned that “brute force cannot settle questions of right and wrong.” “The South was in the right,” he maintained, noting that “the cause was just; that the men who took up arms in her defense were patriots.” And yet he still went further, denouncing the character, motives, and actions of the North and suggesting that it was southerners, not northerners, who had been more devoted to the Union. “Against the South was arrayed the power of the North, dominated by the spirit of Puritanism,” he intoned, “which … worships itself and is unable to perceive any goodness apart from itself, and from the time of Oliver Cromwell to the time of Abraham Lincoln has never hesitated to trample upon the rights of others in order to effect its own ends.” When he was finished, newspapers reported that the crowd leapt to their feet in thunderous applause.

As news of Cave’s remarks made its way northward, a storm of denunciation flowed from every corner of the nation. From newspapers in Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Portland, Oregon, came headlines of “Unreconstructed Rebel” and “The Rebel Yell is Heard: Treason Preached at Richmond’s Monument Unveiling.” The Washington Post declared Cave’s statements out of place in this “era of reconciliation,” reminding southerners that Union soldiers had recognized the “valor, the devotion, and the fine manhood of the Confederates” and tried to spare “them every possible humiliation in their defeat.” Surely the South would denounce such brazenly treasonous speech, the paper observed. A handful of southern papers did dismiss Cave’s remarks as ill-conceived and hardly representative of the South, but many southern newspapers either reprinted his speech without any commentary or explicitly endorsed him. And each time they did, northern papers responded in turn. With each salvo, the conflict continued to escalate.

The Richmond Times rushed to defend Cave and to reject claims of northern magnanimity at Appomattox—part of the foundation for reconciliation. “What did that ‘affectionate’ and ‘magnanimous victor’ next do?” the paper asked, “He subjected people of the South to a rule of thieving carpetbaggers, voted into place by a population of ignorant, semi-barbarous slaves and sustained in place by the bayonets of that ‘affectionate and magnanimous enemy.'” By invoking the “evils” of Reconstruction, the Richmond paper had broken the precarious compromise implicit in the Reconciliationist memory of the war. Similarly ignoring the compromise, the Chicago Daily Tribune fired back, attacking both Confederate soldiers’ honor and their cause: “They were not defending their common country,” the Tribune declared, “They were trying to disrupt it … The Confederates fought for the perpetuity of slavery and the destruction of the National Union.” The paper went on to forcefully declare, “[the Confederate] cause was wrong.”

The real battle, however, erupted not between newspapers but among veterans. In early June 1894, the Columbia Post GAR of Chicago wrote to the Lee Camp of Confederate Veterans in Richmond; the letter was republished in northern newspapers. Two years earlier, the Columbia Post had travelled to the former Confederate capital, where they enjoyed “the hospitality and generous welcome” of the Lee Camp. But upon hearing of Cave’s oration they were outraged. The Columbia Post informed the Lee Camp that on the very day Cave had delivered his oration, they had joined with Confederate veterans in Chicago to decorate the graves of Confederate prisoners of war without mentioning the cause of the conflict or its final settlement. Certainly, they felt, the Lee Camp that had so graciously hosted them would not endorse Cave’s statements. “If the sentiments uttered by Rev. Cave … and [the] ‘tremendous applause’ from the audience assembled there, be the true sentiments of the average ex-Confederate veteran,” they noted, “then will it indeed be hard to ever heal the breach between ‘brothers of one land,’ engendered by that awful conflict, and the generous action of our Union veterans seems truly wasted.” Invoking Reconciliationist sentiment as a way to contest Cave’s combative Lost Cause rhetoric, the Union veterans noted that, “While anxious to look with pleasure upon these reunions in your sunny South land, we cannot but regret such disloyal sentiments as these, and must protest in the name of the fallen of both sides.” In the estimation of the GAR, the Confederate veterans’ insistence on defending Cave’s statement displayed a new surge of rebel disloyalty, more than thirty years after secession.

Upon receiving the letter, the Lee Camp was at first unsure how to respond. Some favored tabling the discussion in order to avoid a national controversy, while others remained indignant. But continued newspaper coverage stirred the debate, with one southern paper referring to the Chicago GAR post as “a lot of hoodlums, cattle, and vulgarians.” Soon other Confederate organizations began to rally behind Cave. The Southern Women’s Historical Society of St. Louis sent the reverend their “heartfelt thanks,” while the Pickett Camp of the United Confederate Veterans voted to remove the photograph of a Federal officer from its camp walls.

Finally, in July—more than a month after the unveiling—the Lee Camp responded to the Columbia Post. Expressing shock at the post’s response to Cave’s speech, the Confederate veterans observed that while they did not suspect “any purpose on your part to provoke sectional controversy or add fuel to the dying embers of sectional hate; but such seems to be its natural tendency.” The Lee Camp proclaimed itself unable to understand how Cave’s words could be interpreted as “disloyal” and affirmed his contention that Appomattox had settled the military questions but not the Constitutional ones. “Physical might cannot determine the question of legal or moral right,” they observed. They noted that both sides had erected monuments to their respective causes, and that they too had laid flowers on the graves of their former foes. But most importantly, the camp noted that Cave had not spoken on Memorial Day or a monument unveiling at a battlefield in which both sides were meant to be honored. Instead, “his oration was delivered at the unveiling of a monument to the private soldiers and sailors who died in behalf of the Southern cause, in resistance to an armed invasion of their native land, and in defense … of their personal liberties and constitutional rights.” It was therefore right, they argued, that “he should also refer to and vindicate ‘the cause for which they fell.'”

This was the crux of the matter. Confederates believed that they were free to observe, defend, and memorialize their cause when speaking only to other Confederates. For them, the Lost Cause was the primary memory of the war. When they came together at Blue-Gray reunions or battlefield dedications, they were willing to embrace Reconciliation and remain silent on the issues of causality and consequence. But when honoring their cause among their brethren, they would not be silent. And the same held true for Union veterans. They, too, espoused not only the righteousness of the Union cause—and in many instances, Emancipation—at GAR functions and monument dedications, but they readily held that the Confederate cause had been wrong and without moral worth.

Perhaps it is not surprising to find Confederates defending their cause or Union veterans doing likewise. But the commotion caused by Cave’s remarks and other such incidents force contemporary Americans to reevaluate our understanding of Reconciliation and larger patterns of Civil War memory. They reveal that even though Reconciliationist sentiment might have reached its apex in the 1880s and 1890s, it was never complete nor uncontested. Nor was it the dominant interpretation of the war. Instead, veterans and civilians from both sides tenaciously clung to their own cause, whether that was the Union, Lost, or Emancipationist. Attention to continued divisiveness among veterans also reminds us that Reconciliation was not solely based upon a white-washed memory of the war, as historians have argued. In this case, as in countless others, northerners had not forgotten (or agreed to forget) that slavery caused the war. This was not the issue that stirred so much antagonism; rather, it was the GAR Post’s insistence that rhetoric such as Cave’s was disloyal. Reconciliation was therefore built on a compromise much more tenuous than the veterans who met at Luray in 1881 predicted, and much more complicated than historians have so far acknowledged.

The battles that ensued in the decades after the war were more than just semantics, boasting, or even nostalgia. Instead, veterans of both sides employed competing memories of the war, its causes, and its consequences to advance their own personal and political agendas. At monument dedications, GAR post meetings, or Confederate reunions, veterans revived the animosities of 1861-1865 for reasons ranging from rousing partisan furor in the name of political power to fear that their sacrifices were being forgotten by the next generation. Union veterans simultaneously recalled their pride in the American flag and their loathing of the slaveholding oligarchy when they waved the bloody shirt. Former Confederates defended their actions as sanctioned by the Constitution and rejected the notion that Union soldiers had marched off to war to free the slaves. In the process of remembering and defending their respective causes, the veterans of both sides ensured that Reconciliation would not come to dominate the landscape of Civil War memory—at least during their lifetimes.

But where do we stand 150 years after the war? So far, the sesquicentennial has left us with a mixed legacy with which to judge war memory. Countless journalists, event organizers, and other public figures have embraced Reconciliation, resurrecting the images of the Blue-Gray love fests. There was no right or wrong cause, they argue—northerners and southerners both believed they were right. Others have emphasized Emancipation, using commemorations to correct what they perceive as versions of the war that focus only on white combatants, highlighting instead slavery as the war’s primary cause as well as the contributions of African Americans to both emancipation and the overall war effort. Still others have feared offending either those who still promote the Lost Cause or those who advocate an Emancipationist memory, electing to forego any observance of the 150th anniversary. Hence there is no national sesquicentennial commission, and only a handful of state commissions devoted to marking this moment in American history.

It is too soon to tell exactly what the sesquicentennial’s overall impact will be on the course of Civil War memory. But several issues remain clear. First, Reconciliation never was, nor has it ever been, the predominant memory of the war. Try as they may, Americans have never succeeded in finding a memory of the war that absolves all parties of blame and is palatable to northerners and southerners, white and black, men and women. Second, slavery was not forgotten by the war generation—not by white Union veterans, Confederates, or African Americans. To somehow “discover” that slavery was at the center of the conflict is patronizing to those men and women. Finally, it is clear that the Civil War is far from forgotten. Indeed, it seems likely that for decades and perhaps generations to come, Americans will continue to grapple with questions of the war’s memory, of what to commemorate and what to condemn.

Further Reading

On reconciliation, see Nina Silber, Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865-1900 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1993); David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American History (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); Timothy B. Smith, The Golden Age of Battlefield Preservation: The Decade of the 1890s and the Establishment of America’s First Five Military Parks (Knoxville, Tenn., 2008).

The literature on the Lost Cause is voluminous. Readers might begin with Gary W. Gallagher and Alan Nolan, eds.,The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History (Bloomington, Ind., 2000); and Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South (New York, 1987).

For historians who have discussed the Union cause at length, see Gary W. Gallagher, The Union War (Cambridge, Mass., 2011); and John R. Neff, Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation (Lawrence, Kansas, 2005): 8-10.

On the Emancipationist Cause, see Blight (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); and Kathleen Clark, Defining Moments: African American Commemoration & Political Culture in the South, 1863-1913 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2005).

This article originally appeared in issue 14.2 (Winter, 2014).

Caroline E. Janney is associate professor of history at Purdue University. She is the author of Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation (2013) and Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause (2008).