Toward Meaning-making in the Digital Age: Black Women, Black Data and Colored Conventions

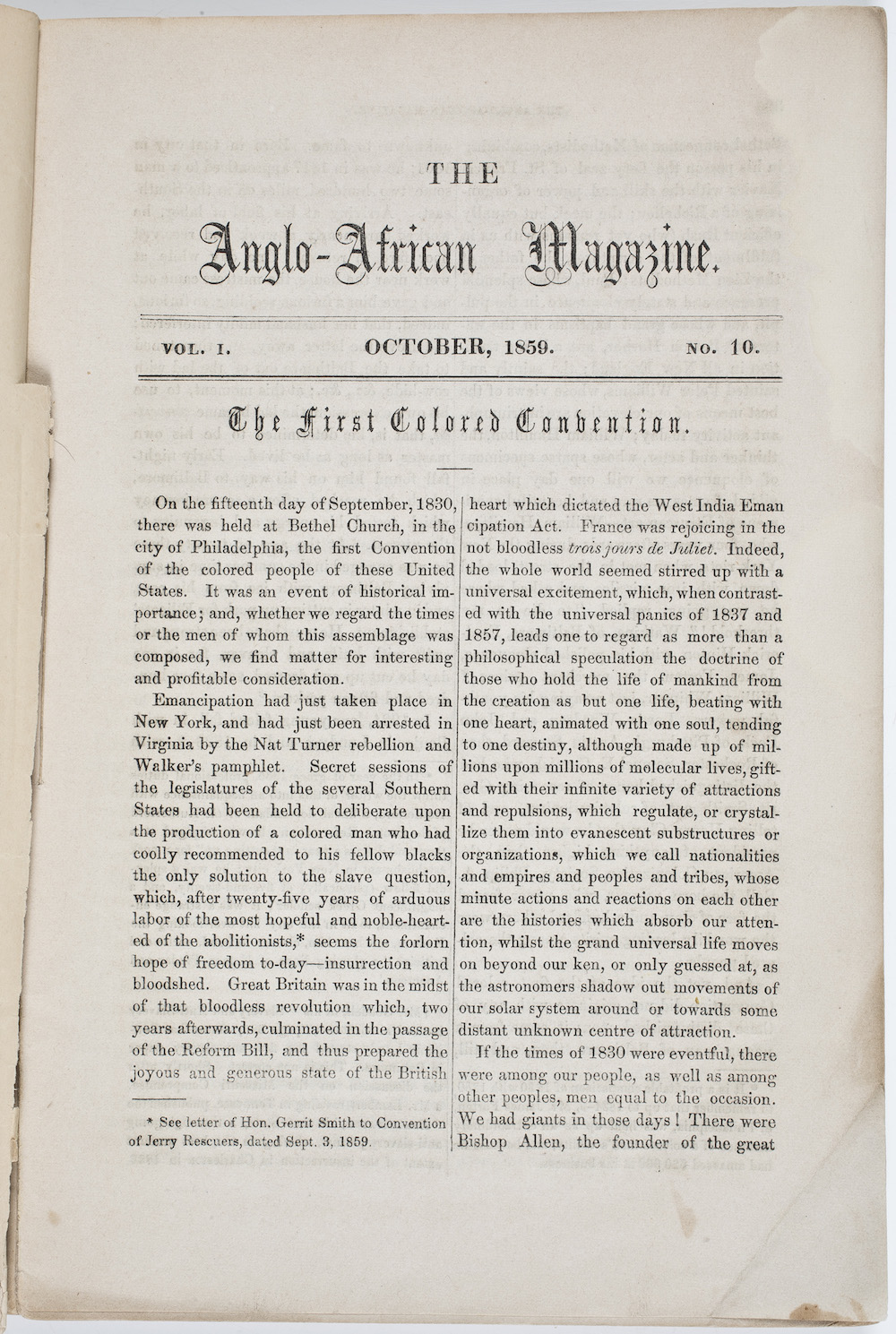

On May 9, 1843, a Black delegation gathered for a two-day series of meetings in New York City and resolved to collaboratively write and publish a public call for a national convention of colored citizens. A committee of three writers drafted the call and approximately fifty signers from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania pledged support. The delegation identified the dearth of annual national conventions as a key issue preventing Black-led political organizing from having a stronger impact on the condition of Black people in the U.S. In the reprinted call appearing in minutes of the 1843 National Colored Convention, the signers argued:

Since we have ceased to meet together in National Convention, we have become ignorant of the moral and intellectual strength of our people. We have also been deprived of the councils of our fathers, who have borne the burden and heat of the day—the spirit of virtuous ambition and emulation has died in the bosoms of the young men, and in a great degree we have become divided, and the bright rising stars that once shone in our skies, have become partially obscured.

The call represents Black men’s increasing anxieties about the growing intellectual and organizational distance between senior figureheads and emerging leaders. The signers cite the eight years since the last national colored citizens convention was held in Philadelphia in 1835 as irrefutable evidence of this distance. And yet this call inadvertently creates another form of distance: by focusing on the politics of male leadership, the call truncates Black women’s ideological and economic contributions that also helped to sustain colored conventions’ interests, political viability and cultural influence.

I describe two instances where historical records either ignore (Black women) or misrepresent (Black communities, in general) lived reality. In 2015 the Colored Conventions Project launched online exhibitions to encourage our learning and meaningful exchange about the significance of the colored conventions movement to American political history. Using digital media as a critical lens, I sketch a portrait of Black intellectual cultures by clarifying links between the socio-economic character of Black women, communities and political organizing. I also illuminate the ways in which rich social histories can be charted through open-source digital media by taking as an example the online exhibit “Black Wealth and the 1843 National Colored Convention.” The exhibit highlights the economic and cultural assets of Black people as well as the narratives and initiatives connected to the convention. It especially highlights Black women’s often-underrepresented contributions to convention cultures. The exhibit brings attention to diverse forms of political expression captured in convention proceedings and newspapers while also placing important antebellum Black political conventions in a broader context of regional Black political activity.

More than a century before the digital age emerged, Black activists sought to translate a multitude of Black experiences into records about Black life that could answer the question: what is the condition of free Black Americans? For these Black thinkers, data describing individual and collective achievements forced readers to acknowledge Black Americans’ contributions to contemporaneous nation-building efforts. Departing from styles of biographical writing that cage Black women’s economic and political roles within patrilineal narratives about their husbands, fathers and brothers, the exhibit “Black Wealth” situates Black women as the leaders, educators, and entrepreneurs that their life stories prove them to be. Scholars have traditionally studied and characterized colored conventions with men as central points of entry into convention cultures and ideological debates. By moving Black women from the margins to the center of the exhibit, the Colored Conventions Project makes a crucial intervention in the historiography of the colored conventions movement. The exhibit’s tabulations depict a collective image of Black antebellum life taken from data reports presented by the convention’s Committee on the Condition of Colored People. By extrapolating and visualizing these reports, the project inserts Black-led, census-style reports into politics surrounding Black Americans’ struggles for power over self-determination. Working toward meaning-making in the digital age, this essay interrogates the intellectual and economic connections between Black women, Black data and colored conventions in the antebellum era.

Colored Convention Cultures: Black Women’s Economic Prosperity and Census-Style Reports

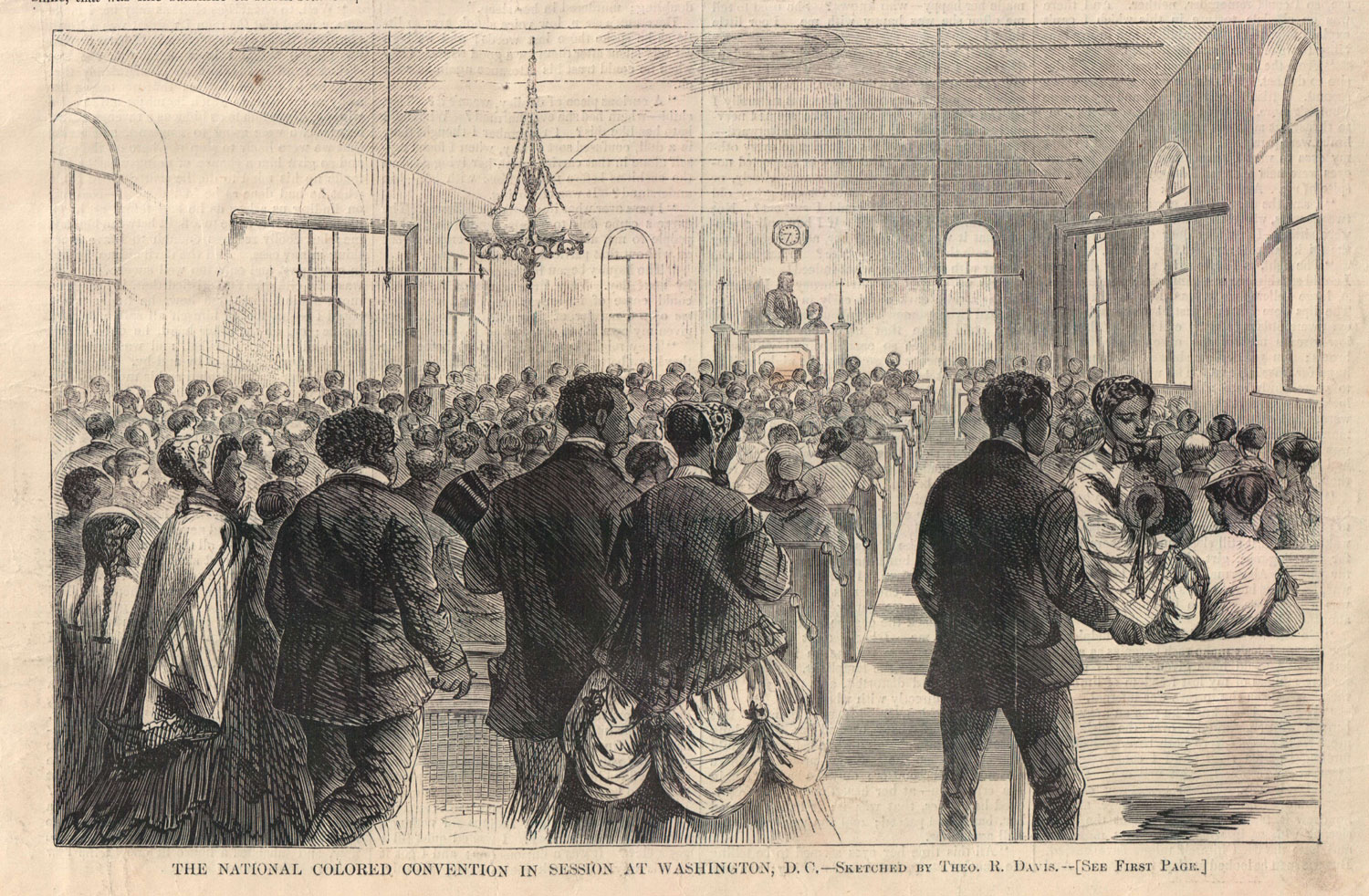

Delegates of the 1843 national convention emphasized Black communities’ diverse labor and entrepreneurial pursuits, characteristics they thought would best communicate a diverse number of Black communities’ economic achievements and potential. Fifty-eight credentialed delegates met to debate various subjects before a lively audience. The men discussed delegates’ voting rights, regional favoritism, the role of Christianity in Black political organizing and the effectiveness of collective insurrection to securing civil liberties for oppressed Black people in the U.S. Many of the convention’s most celebrated Black leaders, including William Wells Brown, Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, James N. Gloucester, and Charles B. Ray, represented Massachusetts and New York. Indeed, this convention is best known for the heated debate that ensued when delegates voted on whether or not to endorse Garnet’s “Address to the Slaves of the United States of America”—with Douglass leading the charge against endorsing Garnet’s radical call to arms and defeating its adoption by the slimmest of margins.

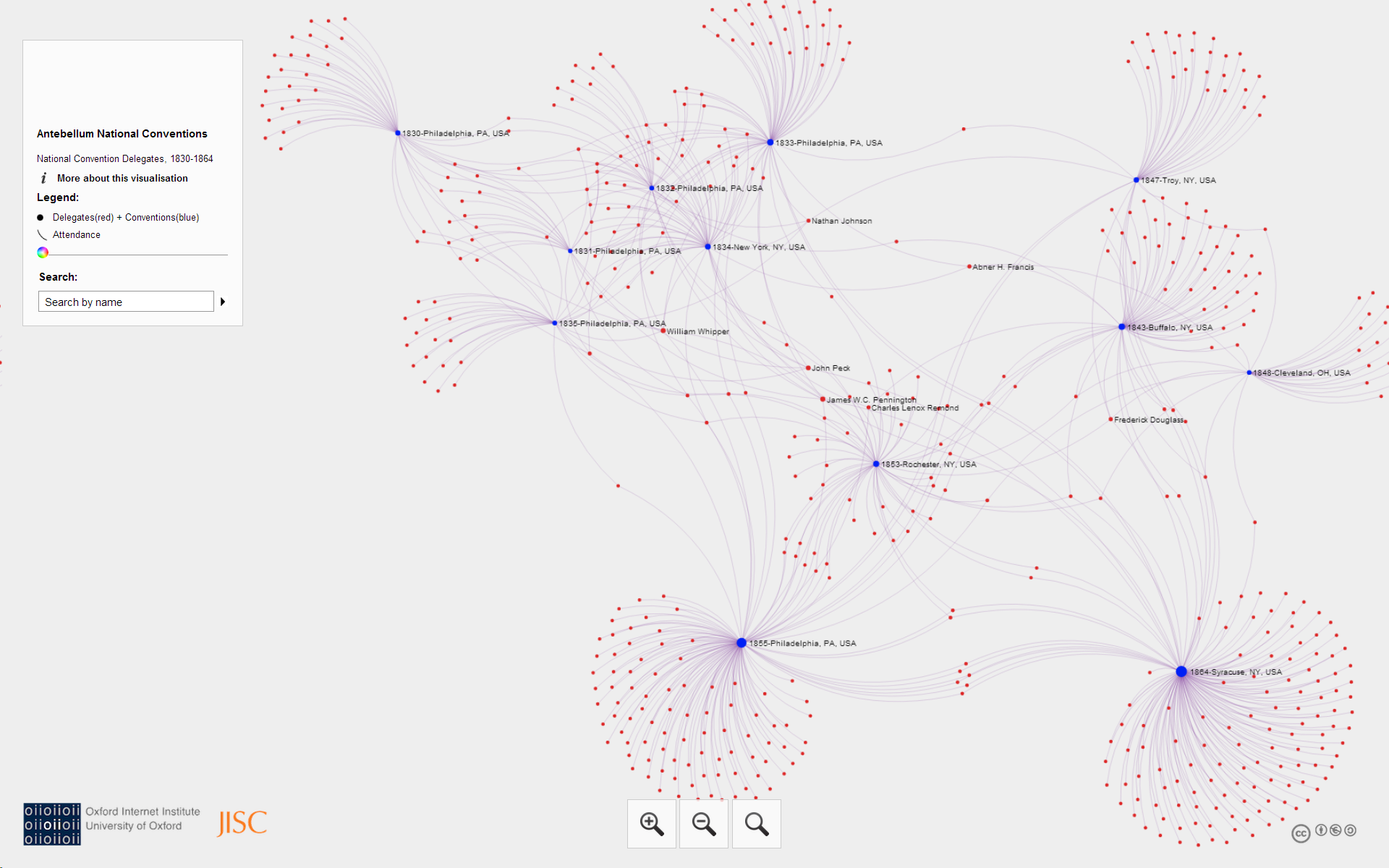

1. Delegate Attendance Trends at National Colored Conventions, 1830-1864. The minutes of the colored conventions movement offer many insights into Black mobility and geographically concentrated activities during the ante- and postbellum eras. This graph charts rates of delegate attendance at national conventions in the northeastern United States between 1830 and 1864.

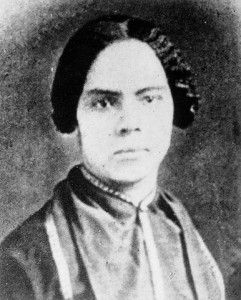

The convention’s publication committee captured and printed many of these leading Black men’s interventions, as did activist-themed newspapers such as The Cleveland Daily Herald, The Emancipator and Free American, and The Liberator. But what of Black women intellectuals and community leaders? Although women are seemingly invisible within the printed proceedings, the Colored Conventions Project’s larger mission is dedicated to highlighting women’s political and economic contributions. Thus, “Black Wealth and the 1843 National Colored Convention” focuses on the socio-economic histories of connected women such as Julia Williams Garnet, Elizabeth Gloucester and Dr. Sarah Marinda Loguen-Fraser. Their prosperity and activism furthered the convention’s principles and missions beyond delegate appointment. In one compelling example, an important member of Brooklyn’s Black bourgeoisie, Elizabeth Gloucester, amassed business holdings and a personal fortune that matches, and in many cases surpasses, that of the convention’s male celebrities.

Elizabeth Gloucester’s economic history—one glimmer in the archives of the Colored Conventions Project—prompts us to explore her activism and professional ties. Gloucester’s husband, James, hailed from a family known to many as a Black ministerial dynasty in Philadelphia’s free Black elite communities. An orphan upon her mother’s death, Elizabeth joined the Gloucester family while just a girl. She grew up in a thicket of activity among Philadelphia’s Black intelligentsia wherein Black religious and political cultures were tightly bound. During her climb to economic eminence in Brooklyn, Gloucester acquired several properties and businesses including second-hand clothing stores, a furniture store, and a boarding house known as Remsen House, which was nestled between Myrtle and DeKalb Avenues, a popular merchant district. As directress of and a fundraiser for the New York Colored Orphans Asylum, Gloucester donated significant sums to the home to further its educational goals and to improve the lives of impoverished children. Indeed, the businesswoman’s properties and organizational affiliates were deeply intertwined with a host of political activities and institutions: Underground Railroad sites, Black churches, literary societies, freedom parades, a women’s commerce and trade group. Gloucester’s economic history is an invaluable conduit by which we understand Black women’s integral roles in promoting the principles and missions of the 1843 national convention. Undoubtedly, Gloucester’s estate and occupations would have been prime evidence to support the 1843 delegation’s interest in validating Black communities’ social value and community development by publishing data reports in the pages of the proceedings.

Because we know that colored conventions were not historically discrete meetings, but were rather embedded in broader historical contexts involving many actors and events, the exhibit likewise highlights Black-led data reports. Convention organizers could only “hope that…every city, town, hamlet, and village [would] be represented as well as Literary and Benevolent Societies” at the five-day series of meetings. But delegates knew that enumeration could defy space, time, and racial bias; they also knew that the federal decennial census apportioned taxes and congressional representation. Even today as we struggle with the dilemma of racial bias in the “historical record” over 170 years later, we should increasingly seek out historical Black data repositories that challenge and complicate our understanding of American (political) history. Such repositories present a compelling opportunity for new investigations into Black data curation. This is especially significant in light of federal reports such as a 1918 Department of Commerce publication that confirms the bureau’s frequent misrepresentations of Black population trends prior to the thirteenth decennial census. The 1843 delegation seized an opportunity to dispel myths about Black people’s economic stagnancy by including statistical and qualitative reports that could reframe readers’ understanding of Black communities’ progress in America.

As James McCune Smith discovered after deftly sifting through the 1840 federal census, the U.S. government had published erroneous and blatantly fabricated calculations on the condition of Black people while simultaneously presenting the still-young federal census as a legitimate means by which Americans and global readers could construe an intelligent understanding of the nascent New World. Labor, educational attainment, family units, service, physical ability—each of these categories, among others, were thought to reflect the general ambition and progress of a young and vibrant nation. McCune Smith exposed incorrect calculations in the census’s population category for Deaf and Dumb, Blind and Insane Colored People, and exposed misleading interpretations of vital statistics on Black people. As the 1843 convention’s statistical reports suggest, some Black leaders viewed faulty calculations and resulting interpretations of the general condition of Black people as threats to free Blacks’ prosperity and uplift initiatives.

Erroneous census records dangerously impaired Black mobility, undermined community building and seemed to render moot the advances Black leaders had made within their communities. Further, such records offered legislators and communities a rationale for discriminatory practices, promoting the idea that free Black populations were disproportionately insane, impoverished, rapidly decreasing, and thus degenerate. For these reasons and others, a number of northern states and western territories in antebellum America passed a series of laws that limited Black travel in and out of the state, that disallowed or restricted Black people’s ownership of land and chattel, that disallowed or restricted Black voting and court testimony rights, and that generally required free Blacks to meet onerous measures in order to live and work. For example, Ohio’s application of Black exclusion laws in 1829 proved an impetus for the colored conventions movement.

Falsified federal census records also threatened Black economic freedom during a time when many Black leaders believed that economic progress among the Black masses would be a ticket to gaining civil rights. How would ambitious Black entrepreneurs know where to settle to start a new business venture? How likely was it that talented Black teachers would travel to and seek out employment in a seemingly economically stagnant school district?

2. Reported Societies in New York, 1843. Black communities often organized and raised funds to support a host of societies that enriched Black communities’ educational, moral, political, and economic well-being. This graph enumerates the number and variety of New York societies that appear in the 1843 report of the Committee Upon the Condition of the Colored People, presented at the 1843 National Convention of Colored Citizens at Buffalo, N.Y. Cities without values reflect absent statistics in the report.

Thus, we should critically interrogate the 1843 convention delegation’s self-reporting efforts as responses to at least two conversations. They should be viewed in relation to racially discriminatory data collection practices apparent in federal censuses and the power they subsequently apportioned. They should also be viewed as responses to intra-communal concerns about Black people’s general elevation. The 1843 convention strategically appointed data collection leaders with access to pecuniary support and to socio-economically diverse Black populations. And, because political philosophy played an important role in data collection processes, these leaders undoubtedly needed to have the intellectual acumen to move reports from aggregation to publication. Elizabeth Gloucester’s husband, James, chaired the reporting Committee on the Condition of Colored People, which included Abner Francis, William Munro, Sampson Talbot, Theodore Wright, and W. H. Yancy. Organizers directed delegates to submit statistical and qualitative information about their constituents and later compiled and printed reports in the minutes. Black elected representatives might have asked simple, survey-style questions: What sort of work do you do? How much money do you earn per year? What types of societies host meetings? How many drunkards and morally degenerate people are among you? They also consulted local, state and private organizations’ statistical data. Black data collectors often lacked sophisticated skills in statistical analysis and contended with limited funding for data collection. Still, their reports accumulated and organized information about Black communities that the U.S. State Department would not gather until 1850. Their reports portrayed a more diverse image of Black free communities while also providing evidence of the sorts of intellectual inquiries that represented their view of free Blacks’ economic vitality.

Delegates initiated the 1843 statistical report with the lofty goal of a large-scale portrait of Black American life. They intended to collect information about Black communities’ character, divisions of labor, and state of well-being or disunion as they existed in the east, west, north and, perhaps most quixotic in ambition, the south. However, the 1843 statistical report ultimately provides occupational, population, organizational, and economic data only for three states: New York, Massachusetts, and Ohio. In relation to cities in the triumvirate states, the stats depict New York City as an organizational hub of numerous societies including men’s and women’s benevolent and literary societies, an educational society, and a public library. Mechanics, merchants, and agriculturalists are among occupations most represented in Albany, Buffalo, and Rochester, N.Y., and in New Bedford, Mass., and Columbus, Ohio. A related report on agriculture was also featured in the minutes of the 1843 national convention. It argues that numerous Black men and their families had excelled at community-building in Ohio, where they collectively owned thousands of acres of land, built schools and homes, and manufactured their own goods. These reports challenged contemporaneous political theories such as the notion that Black people lived longer (and thus better) within the institution of slavery than they had as free people, and that free Black men and women had not contributed to the nation’s economic and social well-being. The 1843 data reports enumerate the labor and social conditions representing what free Black northeastern and midwestern communities had achieved through entrepreneurial diversity and organizational achievement. This brief overview of a colored convention’s ties to Elizabeth Gloucester, a Black woman of incredible success, and its numerical and sociological reports, seeks to broaden what we know about Black informational enterprises and the broader debates to which they are connected.

We continue to confront a striking absence of Black voices and lived experience in historical records, so the onus is upon scholarly and public communities to critically examine and explore a more substantial history of America’s development. The Colored Conventions Project is leading the charge to bring buried histories of Black men’s and women’s political organizing to public audiences. We champion online exhibits as an important form of digital pedagogy. We collaborate with national and local teaching partners, student content contributors and the scholars featured in our forthcoming collected volume to promote innovative undergraduate and graduate research and exhibits. We have also benefited from a historic agreement with Gale, part of Cengage Learning Inc., to feature newspaper articles hosted in its databases. In many ways, the project’s collaborative nature is a reflection of the collaborative spirit so strongly embedded in cultures of the colored conventions themselves.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Sarah Patterson is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Delaware. Her dissertation examines Black intellectual cultures and ideals, particularly through the ways in which Black women’s political writing addresses social reform movements between 1856 and 1910. She is a co-coordinator for the Colored Conventions Project and will co-edit the collection Colored Conventions in the Nineteenth Century and the Digital Age.