Come On, Lilgrim

Recent early American scholarship has worked to underscore the violence and privation that attended the English settlement of New England, in Plymouth and beyond, for settlers and native Americans alike. Outside of early American scholarship, it is a different story. If once we celebrated Thanksgiving because of the Pilgrims, we now celebrate the Pilgrims because of Thanksgiving. The (somewhat sketchy) Pilgrim origins of Thanksgiving commemorate a brief interlude of relative peace and plenty for Pilgrims and the native inhabitants of the land they settled. The gathering William Bradford describes in Of Plymouth Plantation is memorable precisely because it marks a departure from the struggle that preceded and followed it. These details have not prevented Thanksgiving from becoming the heart of an orgy of consumption that runs from Halloween to New Year’s. Increasingly, Thanksgiving feels like the undercard to Black Friday, when we gather to endure scenes of chaos and violence in order to get more stuff. The Plymouth that Bernard Bailyn and Kathleen Donegan conjure also reels with chaos and violence, but this story replaces big boxes and big deals with empty larders and empty stomachs.

In the Plymouth chapter of Seasons of Misery (2013), Donegan frames her analysis around a quotation from Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford: “the living were scarce able to bury their dead.” The portrait she paints is not of buckled shoes and big hats but of starving settlers driven to eating the leather from those shoes. Seasons of Misery is, in Donegan’s words “a study about the unsettling act of colonial settlement, and how English settlers became colonial through the acute bodily experiences and mental ruptures they experienced in their first years on Native American ground.”

In the case of Plymouth, the process of becoming colonial features the display of dead bodies, both English and Indian. The head of the Indian Witawamut, severed from his body by Miles Standish, better known for his role in the courtship of Priscilla Alden, is displayed on a pike in front of the Pilgrim encampment—“the head of one of them stands still on our forte for a terror to others,” wrote William Bradford. The Pilgrims had their own terrors. Facing simultaneous threats of starvation, sickness, and Indian attack, the Pilgrims created a macabre Potemkin village of their brethren. As Phineas Pratt explained, “We asked them wheare the Rest of our friends weare that came in the first ship. Thay said that God had taken them away by deth, & that before thayr second ship came, thay we are so distresed with sickness that thay, feareing the salvages should know it, had sett up theyr sick men with theyr muscits upon thayr Rests & thayr backs Leaning against trees.” This “cadaverous tableau vivant of forest sentinels,” as Donegan calls it, is hard to imagine integrating into our current observations of Thanksgiving, but violence and terror, in Donegan’s account, were the very fabric of Pilgrim settlement.

Bernard Bailyn strikes a similar theme in his 2012 The Barbarous Years, a companion to his Peopling of British North America (1986) and Voyagers to the West (1986). For Bailyn, the experiences attending the British settlement of North America were “not mainly of triumph, but of confusion, failure, violence, and the loss of civility as they sought to normalize abnormal situations and to recapture lost worlds, in the process tearing apart the normalities of the people whose world they had invaded.” Many writers have noted the irony that the declension and dispersal of the Pilgrims that Bradford laments in the later years of his journal was a function of the colony’s growing prosperity. Coupled with the still more popular story of the First Thanksgiving, it is easy to imagine that this feast marked the end of the starving and the beginning of that prosperity.

Bailyn reminds us this is not the case. In the summer of 1623, a new group of settlers had “found a scene that shook their confidence in God’s favor.” The survivors of the Mayflower and Fortune were, Bradford reports “‘ragged in apparel and some little better than half naked.’ They seemed to have lost the ‘freshness of their former complexions,’” a consequence of a diet consisting of fish and spring water. This encounter takes place in 1623, or more than a year after this famous Thanksgiving. These 1623 newcomers, not surprisingly, “all were full of sadness,” all the more so for sharing Bradford’s realization of “the mighty ocean which … was now as a main bar and gulf to separate them from all civil parts of the world.”

Narrating how we got from the precarity of this first Plymouth Thanksgiving in the 1620s to the current terrain of Black Friday and Cyber Monday in the twenty-teens would take more time and space than is available. Suffice it to say Thanksgiving is a complicated holiday. Its inception lies in recirculating a fantasy of settler colonialism dissolving into racial harmony as the occasion to give thanks for the blessings the United States enjoys. Giving thanks properly in 2015 means committing to a ritual of hyper-consumption, where eating to the point of discomfort in order to wake up before dawn to fight strangers for deals on flat screen TVs is a national ritual of gratitude. It is a holiday, appropriately enough, filled with paradoxes. In the United States, we endure long and grueling trips to spend time in rooms with people we only ever see on Thanksgiving, thankful that there is televised football to fill the space where conversation would be. We work long and hard to prepare foods that many people dislike.

These paradoxes found their way into my current research interest in tracing reverberations of seventeenth-century New England in other times and in other places. How do early twentieth-century women’s clubs appropriate the figure of Anne Hutchinson? Why does John Winthrop’s “City on a Hill” address retain so much appeal in a secular and political context for Ronald Reagan? More broadly, why and how do the stories we tell about the English settlement of North America continue to shape and inform U.S. self-image? As one way of exploring these questions, I wrote an essay about statues of the English settlers of New England in Boston and elsewhere for a forthcoming collection edited by Carla Mulford and Bryce Traister.

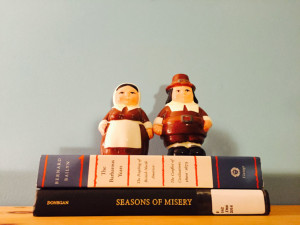

It was not until I had submitted the essay that I realized that some of these statues were already in my house, which is in South Carolina. Publix, the southern grocery chain, offers a festive salt and pepper shaker set for the holidays:

NOW YOU CAN TAKE HOME YOUR VERY OWN PILGRIM PAIR FOR YOUR THANKSGIVING TABLE

THESE HANDCRAFTED CERAMIC COLLECTIBLES ARE AVAILABLE FOR A LIMITED TIME ONLY.

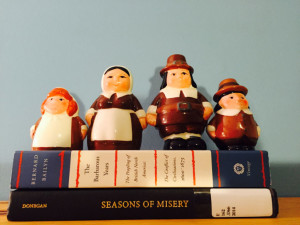

The Pilgrim Pair are also a cherished holiday tradition for many. Other people find them profoundly creepy. Queries on social media suggested that these figures routinely show up on holiday tables in parts of the country served by Publix, and a search of eBay shows that there is a brisk secondary market as well. There is a television commercial where they come to life. The Pilgrim Pair, made in China, is a man and a woman, each roughly egg-shaped. The woman has two holes in her white bonnet (salt) while the man has three holes in his hat with a buckle (pepper). Each Pilgrim or Lilgrim comes with a sticker on his or her bottom that reads “PUBLIX SUPER MARKETS INC.” and the year. There are also Lilgrims, the son and daughter of the Pilgrim Pair.

Generally, holiday collectibles work by offering something to collect. For example, Hess gas stations offer a different toy every Christmastime. There are collectible Budweiser steins, and so forth. But last year’s Pilgrim Pair is the same as this year’s, except for the date. In this universe, there are only Pilgrims and Lilgrims. From time to time, the Pilgrim Pair can assume other forms—gravy boat, napkin rings—but they never have any company.

Their isolation is sad but understandable. If one imagines a typical evolution of collectible figurines, Publix would introduce a new character every year, presumably finding a market for a new and expanded set of figurines. The reason for this deviation from the standard marketing plan is pretty clear—if Publix were to expand its roster of Thanksgiving figures beyond this nuclear family, the logical choice would be their roly-poly Indian pals, which seems like a pretty clear nonstarter. For one thing, in the realm of ceramic collectibles, the specter of mammy doll figures looms over table accessories depicting non-whites. More immediately, portrayals of white settlers and Native Americans for the table can result in unfortunate items like the Dartmouth College Toby mug, where Rev. Wheelock’s Indian pupil contorts himself to be the handle of the mug.

The result is a temporal and racial stasis—in the world of Publix’s Pilgrim Pair, the only thing that ever changes is the year on their bottoms. What happens on the dinner table echoes what happens with the life-size versions of these statues. I learned that there are relatively few statues of orthodox pilgrims and Puritans in New England, but a surprisingly large number far away—in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, to mention a few. As Erika Doss details, the Saint-Gaudens statue of “The Puritan” became an iconic and much-reproduced figure in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century United States. The appeal of a figure like this is a visual invocation of a coherent, Anglo beginning to the national narrative of the United States. Perry Miller’s notion of a “coherence with which [one] can coherently begin” appeals in mass culture, not just scholarship. More generally, the collapse of Plymouth into Massachusetts into New England as the unitary origin of U.S. culture offers a putatively uncomplicated, white story of national origins that is appealing in its simplicity.

The Pilgrim Pair are also remote from the ostensible context they represent. Even as they exist in a temporal vacuum, the symbolic gesture toward Ye Olde New England is a stretch, in that this iconic symbol of Pilgrim colonists is a product of late twentieth-century Florida. Publix is based in Lakeland, Florida, and the Pilgrim Pair debuted in 1998.

More importantly, the Pilgrim Pair are deeply inaccurate: given the starvation that preceded the first Thanksgiving, they are way too fat. Historically accurate Pilgrim figurines would look more like Giacometti statues, and less like Weebles. So what should an early American scholar do when confronted with these tchotchkes on a holiday table? Do they present a dangerously misleading version of history, like, say, Benjamin Martin’s groovy and collegial relations with his free black employees in The Patriot, a film set in eighteenth-century South Carolina? Is it incumbent upon those of us who teach and study early America to dash these saltshakers to the ground, and deliver a disquisition on The Truth?

That would probably be bad manners, not to mention bad pedagogy. But imagining this confrontation with figurines that offer a cheery and whitewashed version of a complex and violent historical moment follows the pattern of many contemporary renditions of early American culture. It is nice to have the public paying attention to early America, but it would be nice if they were paying more or better attention.

To engage this gap between the early America of mass culture and the early America of scholarly monographs, I’d like to propose that we consider a conversation across a smaller gap. As in, for instance, Jane Kamensky’s recent review of Stacy Schiff’s book on the Salem witch hysteria. Jane Kamensky is a prominent early American historian who has spent her entire professional life teaching and researching in this field. Stacy Schiff is an award-winning biographer whose last book was on Cleopatra. As of this writing, Schiff’s The Witches was No. 2 on the New York Times hardcover nonfiction bestseller list. Kamensky is generous to Schiff, and works to praise what she can. The sticking point comes when Schiff’s effort to make this distant past legible to contemporary readers, in Kamensky’s phrase, “takes times out of mind and minds out of time.” As Kamensky explains, in an effort to make Salem legible to her readers, Schiff conjures up analogies such as asserting that “Increase Mather’s 1684 treatise ‘Remarkable Providences’ was ‘an occult Ripley’s Believe It or Not,’ while the durability of a witchcraft accusation ‘resembled an Internet rumor.’”

Kamensky characterizes “this effort to drag the past into the present” as “pandering,” albeit “earnest” pandering. More seriously, however, Schiff’s effort of translation is misleading. I would stress that this difference between incorrect and misleading is an important one for early Americanists who feel compelled to intervene in the case of careless popular appropriations like Schiff’s book. There are details in the uniforms the British soldiers wear in The Patriot that are incorrect. There is a wedding reception that is an interracial hoedown in The Patriot that is misleading. And “misleading” itself is complicated, in that it suggests that it might be possible to lead the misled back to the Truth, which suggests a level of positivism that would make most currently practicing scholars of the humanities uneasy.

In this situation, one approach is the “well, actually” stratagem, as when Kamensky challenges Schiff’s caricature of Cotton Mather and sets the record straight:

“Poor Cotton Mather, cast by Schiff as a preening, ego-driven throwback who ‘reveled in the occult,’ was in fact not only a leading theologian, but also a fellow of the Royal Society of London—the first elected from the colonies—who helped pioneer the practice of inoculation against smallpox, thus transforming, quite literally, the face of the world, an achievement orders of magnitude more significant than his writings on witchcraft.”

What would the equivalent strategy look like for the Pilgrim Pair? Thanksgiving is already a holiday that has a public “well, actually” narrative baked in. This year’s National Day of Mourning in Plymouth will mark the forty-sixth consecutive year that Native Americans gather on the fourth Thursday in November to share their Thanksgiving counternarrative. It is possible to imagine a program where early Americanists could volunteer to distribute a pamphlet with information about the true context and origins of the Thanksgiving tradition outside of Publix, but Publix does not permit the distribution of literature on its premises, and it is hard to imagine early American scholars agreeing on the text of such a statement.

If we can’t do this work in the parking lot, what about the classroom? Does the proliferation of a willfully idealized and ethnically cleansed version of what might be the most complicated holiday on the calendar offer early Americanists a teachable moment? If it does, the opportunity is less a question of killjoy debunking and more of an occasion to reflect on the power of the Thanksgiving narrative—a power that allows a story from early seventeenth-century New England to leap hundreds of years and hundreds of miles to take root in mutant form in a grocery chain in the deep south in the twenty-first century. For starters, it is worth noting that Thanksgiving is a story of racial reconciliation all the more compelling for its conclusion at the dinner table, rather than in the bedroom.

Kamensky closes her review of Schiff’s book about the other popular New England story with: “To reckon with Salem, 1692, is to peer into a leaded 17th-century window, thick and cloudy and bubbled, not to stare, as Schiff does, in a mirror that reflects most brightly our own self-satisfied faces.” Rather than making an effort to set the Thanksgiving record straight, as history, the first challenge for early Americanists is to understand the appeal of the narrative we see reflected back to us in the faces of the Pilgrim Pair. Instead of looking for our own faces, it is worth reflecting on how an all-white family of ceramic figurines can come to embody a national holiday that celebrates a fantasy of ethnic harmony.

Further Reading:

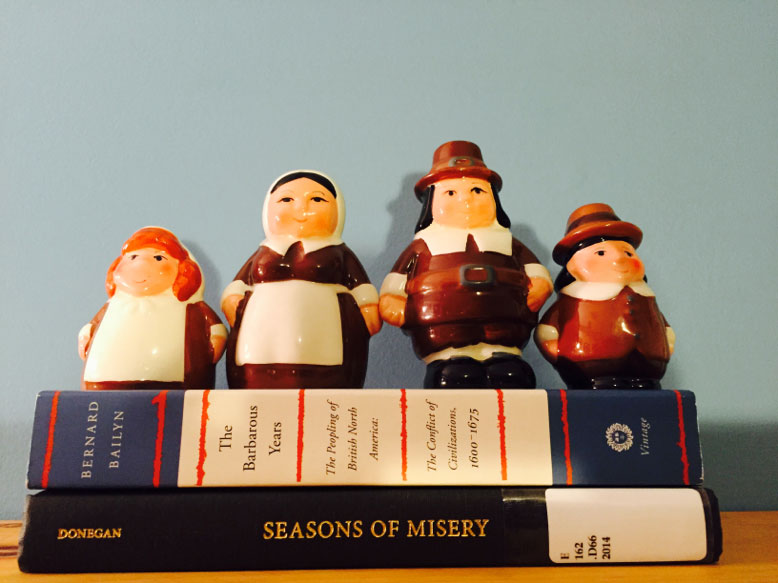

Kathleen Donegan and Bernard Bailyn offer salutary correctives to the narrative suggested by the Pilgrim Pair and their Lilgrim offspring. Both books range far beyond the context of Plymouth to reconsider the English colonial project in the seventeenth-century Americas. Bernard Bailyn, The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America: The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675 (New York, 2012); Kathleen Donegan, Seasons of Misery: Catastrophe and Colonial Settlement in Early America (Philadelphia, 2014). Every early Americanist owes Jane Kamensky a debt for her sober and measured reading of Stacy Schiff’s popular account of the Salem witch trials. Jane Kamensky, “’The Witches: Salem, 1692,’ by Stacy Schiff,” review of The Witches, Salem, 1692, by Stacy Schiff. New York Times, Nov. 1, 2015, Sunday Book Review. For the reader who has not encountered the Pilgrim Pair in real life, and is skeptical of their popularity, a search of Publix + “Pilgrim Pair” on Pinterest or another social media platform will indicate the extent of their popularity. Their online home is here. Erika Doss’s article “Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s The Puritan: Founders’ Statues, Indian Wars, Contested Memories, and Anger’s Memory in Springfield, Massachusetts,” Winterthur Portfolio, 46:4 (Winter 2013), offers a useful account of the appeal of life-size statues of the English settlers of New England.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Jonathan Beecher Field was born in New England and educated in the Midwest. He is an associate professor of English at Clemson University. His essay on bigger Puritan statues will appear in American Literature and the New Puritan Studies, edited by Bryce Traister and Carla Mulford, and forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.