Confronting Slavery Face-to-face: A twenty-first century interpreter’s perspective on eighteenth-century slavery

The challenge of representing eighteenth-century black chattel slavery is to strike a balance between being truthful and being tasteful. To be truthful means to relate enough of the story to be accurate without overloading the visitor with information. To be tasteful means presenting the information in a way that may unsettle, but does not offend the visitor. For the guest who gets offended might deny the existence of the truth. I try to paint a vivid picture of slave life, one that affects the audience’s emotional sensibilities–but not so vivid that they want to run for the nearest exit.

Striking this balance is difficult for any historical interpreter, but it is particularly hard when the subject is American slavery. Most of the visitors to Colonial Williamsburg are upper-middle-class whites. Many of them may be descendants of slave owners, people who had slaves in the family. However, if we confronted them with this truth, bluntly and publicly, most would probably deny it. To work as an interpreter of slavery is to be forever reminded of an uncomfortable fact of American life: people on both sides of the color line are unwilling to face the history of race in America. Even today, being black is still NOT OKAY in this country.

How, then, do we “role play” slavery, confront slavery, remember slavery? If American Jews have learned not to forget the Holocaust, African Americans, for the most part, still turn away from the history of slavery. For the most part, Jewish Americans have recovered financially from their World War II-era losses, have acknowledged that they were victims of Nazi brutality, and are actively working to heal their psychological wounds. In contrast, we as a people are still economically deprived, have bought into the myth that slavery is our own fault, and have very deep and in some cases unexamined psychological wounds.

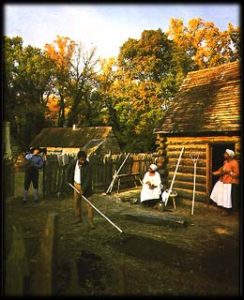

Too often, what we learn in school compounds this collective denial. For most of the recorded history of the United States, African Americans and slavery were purposefully erased from grade school, high school, and even college level textbooks. You only heard about the achievements of African Americans during African American History Month (originally Black History Week). Even at Colonial Williamsburg, our reconstructed “Slave Quarter at Carter’s Grove,” now twelve years old, is still something of a secret. How often have I heard visitors to the Slave Quarter, both black and white, proclaim: “I’ve been here all week, and I’m just hearing about this. How come I never heard about this before?”

With little to prepare them for what they learn at the Slave Quarter, visitors react to our presentations in a variety of ways. Some, especially older white women–I have never seen a man approach me in tears–apologize, weeping for being white, and for their ancestors’ role in the transatlantic slave trade. Other visitors–black as well as white–tell us they grew up in a house that looks like the ones at the Slave Quarter (with or without bathroom facilities). Even today, in the twenty-first century, that lifestyle is a reality for many people elsewhere in the world. Many people cry, and say they are thankful they do not have to live like that now. One of the oddest reactions of all comes from the African American university professors who visit the Slave Quarter and argue over semantics: about when it’s appropriate to use the word “slave” as opposed to “enslaved.”

Perhaps because they know no other way to express their pain, surprise, or anger upon learning about the reality of eighteenth-century slavery, some visitors simply act out. This seemed especially the case in 1999, when our annual theme, or storyline, was “Enslaving Virginia,” an examination of the institution of racial slavery in the colonial Chesapeake and the new nation, and of slavery’s pervasive influence on the lives, fortunes, and values of all Virginians. To help illustrate this point, we portrayed a free black, mixed-race family, living in town at the Tenant House. The wife, Lydia Cooper, was a mulatto. Her mother was white Irish, and while she was clearly of African descent, Lydia spoke with an Irish brogue and carried herself like a fine white lady, as her white Irish grandmother had raised her to do. She often told visitors this, and I have heard some say (even to her face) that she was “stuck up” or “uppity.” Some African American visitors commented, “Humph! She thinks she’s white.”

On occasion, Lydia’s older white cousin, Mary Delaney, would visit the family. By the way, Mary had a child with a black man. One day, when Mary was in the house alone, a white male visitor from Texas happened to visit the house, and remarked to Mary on leaving the building, “We hang ’em in Texas.” He was referring to the blacks on the site, and I do not think he knew that her character was a part of the mixed-race family. After the man left, the white interpreter who portrayed Mary burst into tears, unable to continue her work for the rest of the day. How can you be both truthful and tasteful when confronted with such comments?

I, too, have heard my share of uncomfortable responses to the uncomfortable truths we present. Last year my director passed along to me a letter from a visitor who had been infuriated by my interpretation. I highly offended her with the style of my delivery at the “Enslaving Virginia” lecture, a thirty-minute lecture/discussion forum where both interpreters and visitors can learn more about and openly discuss various aspects of slavery and its impact on us today. The woman wanted information about the slaves given in teeny, tiny bits, just a couple of little disembodied facts. She wanted facts given out of context without the meaning to the slaves or their owners. She was pleased with the interpretation she received on another tour from a white blond male on a previous trip, and from a white blond female she received on the same trip. Both apparently did that for her.

Of course, white visitors hold no monopoly on acting out. This past spring, an African American woman came to visit the “Slave Quarter at Carter’s Grove.” As she stepped across the bridge from the reception center and caught sight of the quarter, the woman began shouting to me: “Cousin Hattie! Cousin Hattie!” all the while doing the “step-and-fetch-it” walk. I was the only African American female interpreter in front of the Slave Quarter at the time, and I was standing in the middle of a group of several seated interpreters, which made me look like the elder of the group. As she approached, the woman continued shouting, “Cousin Hattie, Cousin Hattie! Don’t you remember me? I was yea high . . . I’m Susie Mae’s daughter from Indiana.” Finally, when she reached me, she said, “Cousin Hattie, now ain’t you gonna give your cousin a hug?”

What was I supposed to do? I thought to myself, “I do not know her, and nobody here seems to know her. She’s not being violent, and if I confront her with this behavior, she may become belligerent. So I will play along with her. Maybe that is what she needs to do to deal with being here.” So I hugged her, and I asked, “Now what is my cousin’s name?” The woman replied, “Carol.” She seemed happy and satisfied. From there Carol disappeared into the first slave quarter building, and we never heard another peep out of her. Perhaps she was having flashbacks to Hattie McDaniels in Gone with the Wind. Perhaps the reality of the setting was too much for her. Or, perhaps, like the white woman who wrote the letter, she could not handle this much reality at once! Was it again too truthful to be tasteful?

Some visitors, both African American and white, are surprised and even offended to see whites working at the Slave Quarters and leading Afrocentric tours and lectures, including the “Other Half” tour, the “Enslaving Virginia” tour, and the “Enslaving Virginia” lecture. A few have even gone so far as to refuse to listen to the white interpreter, preferring to either demand an African American tour guide, to wait until an African American tour guide was available, or to leave the lecture after making their feelings known. In cases like this, at the Slave Quarter, an African American interpreter usually comes forward to defend the white one, telling the visitor that none of us is in character, that the Foundation has trained all of us with the same information, and that the white person knows the subject matter.

And yet, for all that, I am still troubled by the issue: why was a white person teaching about black history? My personal answer to that question goes back to an expression I heard long ago. White people can do the watusi, but black people ARE THE WATUSI! No matter how much a white person reads about slavery in general, about the transatlantic slave trade, and about the African American experience today, those experiences are just words on a page. I am happy that America is finally discussing diversity, that many of our children do not see color, and are allowed (at least in some circles) to fully embrace their heritage. However, the danger is, if we forget our past we are doomed to repeat it.

Author’s note: The views represented here are strictly my own, and in no way reflect the official position of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

This article originally appeared in issue 1.4 (July, 2001).

Karen E. Sutton is a historical interpreter in the African-American Programs & History Department, Division of Historic Presentations, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, where she has just completed a pilot project to identify descendants of the slaves from Carter’s Grove.