Containing Multitudes: The Biography of a Book

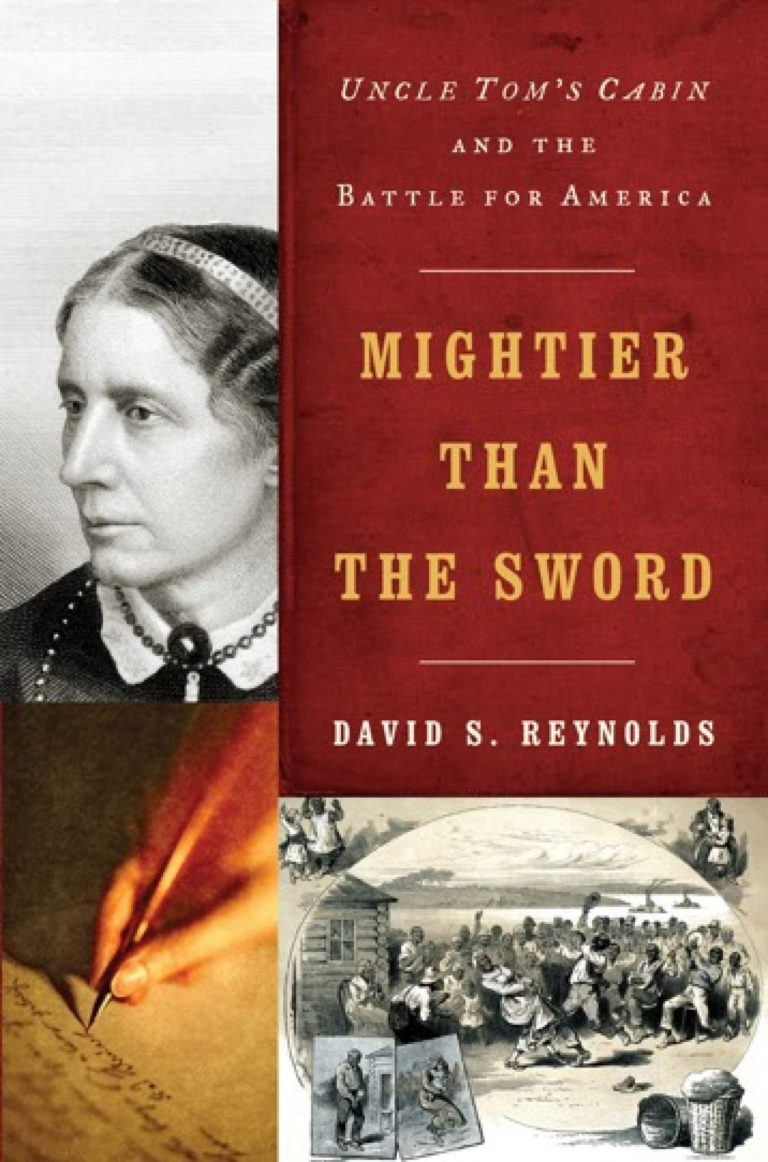

With Mightier Than the Sword, Reynolds has written the biography of a book, and 2012 might be the perfect time to read it. As the wired world celebrates Twitter revolutions and the cultural power of the 140-character microblog, we citizens of Facebook nation have come to suspect that books will soon be a thing of the past. At a time when the concept of an author’s words sandwiched between two covers seems a little quaint, we might finally be ready to rediscover what a really powerful book can do. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin is that sort of book, and if Reynolds’s study of it convinces readers of anything, it will be that they have somehow underrated the cultural importance of a novel that many already believe launched America’s bloodiest war. First printed in serialized form in issues of The National Era in 1851 and 1852, UTC was quickly published as a bestselling anti-slavery novel. It has been in print ever since—outlasting slavery, its author, and any number of supposedly earth-shattering novels that are now long forgotten.

More important than its life in print, though, is how from its first appearance the novel thoroughly permeated the culture that created it. Within months of its publication it was already being adapted to the stage, and its dramatic productions, as Reynolds points out, would for many decades reach far more Americans than Stowe’s novel could. Almost instantly, its compelling characters became the subjects of everything from figurines to children’s games. Tom Mania spanned the Atlantic, surging into Britain, the Continent, and even Tsarist Russia, and the story brought a huge number of international readers to sympathetic tears. It did not, however, have the same effect on white Southerners. Rather, its most immediate result was increasing the already heightened sense of sectional divisiveness that defined the last antebellum decade in the wake of the Compromise of 1850 and its strengthened Fugitive Slave Law. As more and more Northerners began to regard the actuality of American slavery through the lens of Stowe’s fiction, slaveholders and their supporters dug in their heels and clamored in protest. As the war of words heated up, it would bring new and bloody violence to Western territories and the floors of Congress, and help make the Civil War irrepressible. Stowe’s novel had attempted to fight with weapons of the heart and had not called for a war to liberate Uncle Tom and his fellow slaves. Her book helped bring on the Civil War only through a complex chain of powerful responses and reactions that the author herself could hardly have predicted, and which would continue to ripple through the postwar years right up to the present day.

By tabulating complex influences and diverse responses—from Tom shows and white supremacist narratives, to Hollywood films and televised miniseries—[Reynolds] offers readers a richly informative and entertaining work of scholarship, a generation-spanning account of American race relations, and a testament to the power of a book to change history.

This is the story Reynolds wants to tell, and he is not interested in offering merely a new literary interpretation or a sense of historical context. These are small fry; the big fish he is angling for is indicated in his rather grandiose title. He is seeking an understanding of how Stowe’s pen came to be mightier than the sword—or at least came to be the sort of pen that makes swords necessary. As he traces the cultural developments preceding, surrounding, and emanating from one of the most historically significant novels ever written, he is also explaining how literature achieves cultural power. By tabulating complex influences and diverse responses—from Tom shows and white supremacist narratives, to Hollywood films and televised miniseries—he offers readers a richly informative and entertaining work of scholarship, a generation-spanning account of American race relations, and a testament to the power of a book to change history. His book should be of special interest to scholars working in American studies and nineteenth-century literature, but its sparkling and sprawling narrative should also appeal to general readers.

Reynolds’s historical descriptions and close readings are engrossing in their own right, but they also support a thesis that helps organize and connect the book’s first and second halves. The first three chapters—on antebellum religion, popular culture, and antislavery rhetoric—address Stowe’s influences and how UTC managed to weave together many important strands of antebellum culture into a uniquely powerful novel. The second half tries to demonstrate the book’s monumental impact in three chapters that explore a wide array of adaptations, refutations, and passing references that extend into the twentieth century and beyond.

Although it may not become fully clear until nearly the book’s midpoint, Reynolds believes that the two sides of this story are indelibly connected: he argues that Stowe’s original synthesis of innumerable cultural forces led to the novel’s broad and longstanding influence. The first few chapters describe a dizzying variety of occasionally contradictory elements that Reynolds finds shaping the novel’s construction. Yet just as readers are ready to assume this cacophony of contradictory impulses have snuck in while Reynolds wasn’t looking, he gathers the squawking brood under his authorial wing. “[T]here is no single source,” Reynolds insists. “All kinds of cultural phenomena—visionary fiction, biblical narratives, pro- and anti-Catholicism, gender issues, temperance, moral reform, minstrelsy—contributed to the novel” (87-88). This range of influences, according to Reynolds, helps explain Uncle Tom‘s later significance. Although many have sought the single “key” to Uncle Tom‘s construction, Reynolds believes that “to isolate individual sources strips the novel of suggestiveness and diminishes what may be called its distributive power: its capacity for generating varied responses in different contexts” (188).

Reynolds’s resistance to root causes or uniform effects means, in practical terms, that he can range widely in both sections of the book. Influences proliferate, effects expand to include distant times and lands, and the reader gets to enjoy a decidedly lively literary history. Reynolds’s determination to emphasize the novel’s capacious dimensions also allows him to take a fuller measure of the cultural complexity that produced it. In the first of the influence chapters, for example, Reynolds focuses on religion but wisely avoids trying to wrangle the complicated spiritual shifts of the antebellum period into a pat set of categories. Thus he portrays strains of religious thought and feeling that are more varied, convoluted, and dynamic than the reader might expect. The dominant Christianity of Stowe’s time and place, Reynolds tells us, was in the midst of a profound transition away from traditional Calvinism and into new engagements with broader social activism and humanitarian passions. Because no family in America seems to have been more embroiled in this religious ferment than the Beechers, it is no surprise that the spiritual voice of UTC captures the tone, if not the content, of a surprising combination of half-abandoned orthodoxies. Reynolds shows how the disciples of a new “religion of love” dug the Puritan tradition out of its grounding in Calvinism and redirected its reformist energies toward fresh social causes. While the pragmatic social reform of the sort pursued by Harriet’s father, Lyman Beecher, is still hard at work in her novel, it competes with the passionate appeal represented by her brother, Henry, and the era’s sentimental preference for the heart rather than the head. In this unruly chapter, a range of reinterpreted dogmas and unexpected interests dishevels the image of the author of UTCas a straight-laced Christian crusader. Stowe’s staunch scriptural faith is complicated by flirtations with spiritualism and trance writing. The novel’s sense of ecstatic vision turns out to be Roman Catholic, but it arrives yoked to the distrust of religious authority that energized the anti-Catholicism of nativists and know-nothings. If this seems contradictory, so be it; as Walt Whitman, another of Reynolds’s antebellum subjects, once proclaimed, we are large, and contain multitudes.

Reynolds’s refusal to apply modern categories to the messiness of nineteenth-century culture can sometimes yield what seem like excuses for prejudice and oppression, and some readers may be bothered by his tendency to judge works according to the moral standards of their times rather than our own. But that same resistance to contemporary standards also allows him to share some rich connections that otherwise might be difficult to recognize. In a chapter on popular culture, for instance, he refuses to describe the novel’s representation of women as either subversive or conservative, but that refusal is no mere shrug. Rather, Reynolds argues that Stowe was intentionally staking out a “middle ground” between available positions on women’s roles, while arguing that she did so in Uncle Tom in order to deliver “daring ideas and images in conventional wrapping” to a mainstream audience (45). But Reynolds also points out that Stowe derived this strategy from a whole range of nineteenth-century popular literatures that profited by presenting subversive material under the mantle of respectable conventions. Reynolds catalogs titillating antebellum accounts of vice that appeared in print as crusades to reform drunkenness, crime, and Catholicism; these, he suggests, served as models for Stowe’s muted but still sensational descriptions of slavery and the treatment of women in UTC.

After the first half of his study, Reynolds moves from an effort to identify Stowe’s precedents to a celebration of the novel as an unprecedented phenomenon. The chapters on “Igniting the War,” “Tom Everywhere,” and “Tom in Modern Times” offer deep analyses of some of the more obvious and important responses to Stowe—the move toward war being chief among them. Yet there are more surprising outcomes here as well, as Reynolds traces the novel’s role as a reference point and argument partner for a vast array of cultural productions. Already in the first chapter on the novel’s results, UTCseems to have inspired the modern play, the interracial working class, Leaves of Grass, “Benito Cereno,” and (I’m fairly sure) vaudeville. While most readers would assume that the novel inspired anti-slavery agitators and Southern apologists alike in the antebellum period, later responses to the novel in the penultimate chapter figure largely in the “mammoth contests over versions of American history” that David W. Blight has found at the heart of postbellum nationalism. Later still, the book becomes a pivot point in the emergence of the American century and the Jim Crow era, and a catalyst for a slew of major national and international events including the Russian Revolution. True, when Reynolds asks the rhetorical question, “Did Uncle Tom’s Cabin save Lenin’s life?” readers will likely respond with a fairly unanimous “no” (225). Nevertheless, even such relatively unconvincing claims are suggested by fascinating evidence. Lenin’s Eliza-like escape across breaking ice to Finland was clearly too sumptuous not to include, and Reynolds’s reading of this dramatic flight may be somewhat tongue in cheek. Furthermore, the author more often than not is able to make a surprising connection stick. Reynolds copiously documents communist revolutionaries’ attachments to UTC, and finds similarly striking ties to the early leaders of the Niagara Movement and the NAACP.

By the time readers reach the era in which the “Uncle Tom” epithet has become more familiar than Stowe’s character, they may be wondering whether they are still dealing in any substantial way with an antebellum novel’s influence. Is Uncle Tom merely marching in a grand cultural parade or is he leading the band? And is it still Stowe’s Uncle Tom, or someone who only happens to share his name? That question about the degree of literary influence may be only mildly disconcerting when the book arrives at Birth of a Nation in 1915, but it becomes more urgent when Tom still seems to be hovering over the martyrdom of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. How much, the reader may wonder, does this really have to do with Stowe’s book? Reynolds wonders about this, too, but the fact that the same question has been asked almost without ceasing since 1851 reinforces his point about UTC‘s importance. Ever since its first serialized publication, the novel has encouraged serious reflection on literature’s historical effects, a scholarly activity that, as Reynolds’s enriching explorations demonstrate once again, is worth pursuing even if the quest turns out to be endless.

This article originally appeared in issue 12.4.5 (September, 2012).

Samuel Graber is an assistant professor of Humanities and Literature in Christ College, the interdisciplinary honors college of Valparaiso University. His articles have appeared in the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review and American Nineteenth Century History. He is currently revising a book about transatlantic influences on the representation and remembrance of the American Civil War.