Convention Minutes and Unconventional Proceedings

This piece narrates the Colored Conventions Project’s work to transcribe, catalogue, and visualize the minutes of the nineteenth-century Colored Conventions. I describe the CCP’s public and collaborative process, but this account does not mean to be prescriptive or formulaic. Our experiences offer an example of how digital collections can become a common space where public audiences can collaborate in meaningful ways and fuel innovative research. Transcribing, cataloguing, visualizing: the processes of public digital history compel us into ever more intimate and wide-ranging knowledge of the conventions.

Recognizing the uses and limits of the convention minutes

As Curtis Small describes in his piece for this roundtable, the project’s collection of Colored Conventions minutes provides unprecedented ease of access to these rare texts. In 2014, as our project developed, we grew increasingly aware that the digital reproductions of the minutes remained difficult to read or search. The minutes needed to be transcribed to make them not only reliably searchable but amenable to large-scale textual analysis.

What we initially perceived as issues of aesthetics (Does it fit the look and feel of our site?) and usability (Is it easy to use?) evolved into questions about access and authority. We worried about discouraging transcribers.

To transcribe the minutes, we considered a wide range of options. Double-keying the minutes into a word processor far exceeded the project’s capacities and desires, so we looked at Optical Character Recognition (OCR) tools. The range of options for those of us without large budgets or advanced skill sets includes Adobe Acrobat, ABYY FineReader, or any of a variety of Websites that provide free or cheap PDF-to-plain-text conversion. Unfortunately, all of these OCR tools struggled with the eccentricities of nineteenth-century typography in even the highest possible quality images. In our technical challenges, however, we recognized an opportunity. Just as the delegates back then met in public spaces to create the minutes together—with resolutions, songs, and speeches—so too might we transcribe the minutes online with as large and diverse a community as possible.

Transcribe Minutes

We began building Transcribe Minutes in 2015 as a new initiative to create high-quality texts by engaging multiple publics in our work. We joined forces with the University of Delaware Library to build Transcribe Minutes. After reviewing a number of platforms using Ben Brumfield’s guide to collaborative transcription tools, we chose a free, Omeka-compatible tool called Scripto. Scripto follows after most crowdsourcing platforms by breaking a large goal (transcribing an entire document) into smaller tasks (transcribing a single page at a time). As we now invite any and all to help us transcribe the minutes, volunteers can quickly and easily find pages to work on.

Over a six-month development process, we worked with our partners at the UD Library to navigate a range of questions at the nexus of public history and editing. What we initially perceived as issues of aesthetics (Does it fit the look and feel of our site?) and usability (Is it easy to use?) evolved into questions about access and authority. We worried about discouraging transcribers. Should we require them to register for accounts? How much could we ask in editorial markup? Considering our variety of intended audiences and analyses, how faithful to the historical documents should the transcriptions be? All of these questions were undergirded by the security and spam threats that could (and do) try to disrupt our site.

The interface for Transcribe Minutes reflects our efforts to credit and support the transcribers’ contributions. We require user accounts to prevent spam but mainly to credit the transcribers as co-creators of the transcribed minutes. As in figure 1, we populate each page (where helpful) with rough drafts generated by Acrobat so that volunteers can improve rather than create transcripts. These decisions, and the editorial principles expressed in our Advanced Instructions on Transcribing, aim to make it easy for volunteers to contribute substantively.

Public Collaboration with the African Methodist Episcopal Church

Just as the organizers of the nineteenth-century Colored Conventions depended on the strength of African American churches, so has the CCP today. The Colored Conventions originated at Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia in 1830 and AME churches hosted many conventions as far away as California and as late as the 1890s. Given the large number of conventions hosted by AME churches and the AME Church’s historical and contemporary importance, we envisioned a natural partnership facilitated by the Historic Church and Community Liaison we brought in, Denise Burgher. Denise and our project director, Gabrielle Foreman, engaged the AME’s national leadership and worked with the indefatigable AME national Historiographer for the Lay, Pamela Tilley. The AME recruited an army of transcribers with extraordinary energy and commitment, and an understanding of the links between the AME Church and generations of African American leadership and activism. As of this writing in June 2015, together we have transcribed over 1,200 pages from forty-one conventions (and counting). These texts—and those to follow—will be easier to read, search, and share thanks to the efforts of the transcribers from the AME Church. By creating these texts, our partnership further enables the CCP’s experiments with digital research methods for illuminating the lives of hundreds and thousands of important but forgotten nineteenth-century African Americans.

Cataloguing Collaboratively

Once Transcribe Minutes was underway, we redoubled the work of searching for minutes and soon identified more than sixty additional conventions. In response to our rapidly growing collection, project members Jordan Howell and Molly Olney-Zide developed a catalogue of convention records. The catalogue benefited from an interdisciplinary conversation on matters familiar to librarians—including cataloguing, controlled vocabularies, and matching OCLC numbers—and to researchers—sorting out the conventions from among the many overlapping but distinctly different meetings of organizations related to abolition, temperance, education, and labor. That catalogue has proven invaluable for both ongoing research and subsequent efforts to preserve our digital files in the University of Delaware’s institutional repository, UDSpace, to ensure long-term availability.

The Amplifications and Silences of the Conventions Database (CoDa)

The research advantages of the catalogue of conventions inspired us to begin building a relational database of our project’s growing array of information. The Convention Database (CoDa), which we will make available online, provides information on the many people, places, and publications of the conventions. Using the accurate texts generated by Transcribe Minutes, we began systematically gathering our data by compiling the names of convention delegates through a two-pass method using the Stanford Named Entity Recognizer followed by the painstaking work of manually checking and adding any missing names. We are working slowly through the data using a tool called OpenRefine to attend to the messy initials, misprints, typos, and false matches. Additionally, building the database requires encoding the project’s conceptual work into the relationships between the data. It is a slow and deliberative process of dialogue between the project’s leadership, librarians, and Rashida Davis, a computer scientist who recently joined the CCP.

The CoDa thus far contains approximately 3,000 names from sixty-three conventions. Those numbers may double as we obtain more and more records, particularly those from Southern postbellum conventions where delegates often numbered in the hundreds. When public, the CoDa will provide additional information about many delegates’ and connected women’s lives, professions, churches, and travels. The seductive scale of the CoDa makes it important, though, that we remember that the minutes were highly political, mediated documents. Women’s key roles are largely absent from the minutes, but we do not wish to reproduce these historical silences. How can a database account for the conditions of historical silences? Simple categories, and database tables, are often not enough. From a practical perspective, it would be much easier to create a separate database table for the many faint traces of women in the minutes. Instead we need to restructure the central organizing category of “Delegates” in the CoDa to become “People” so that users will encounter “a lady” (Philadelphia, 1832), “One Hundred Ladies” (Schenectady, 1844), or “the ladies of Sacramento” (Sacramento, Calif., 1855) in search results alongside more familiar names like George T. Downing or Henry Highland Garnet. (All this and more are viewable on a map: “Women in the Conventions.”) The questions about gender are yet another example of the deep conceptual issues often implicit in technical questions about database structures, menus, and more that arise in the process of building historical websites.

Social Networks of the Colored Conventions

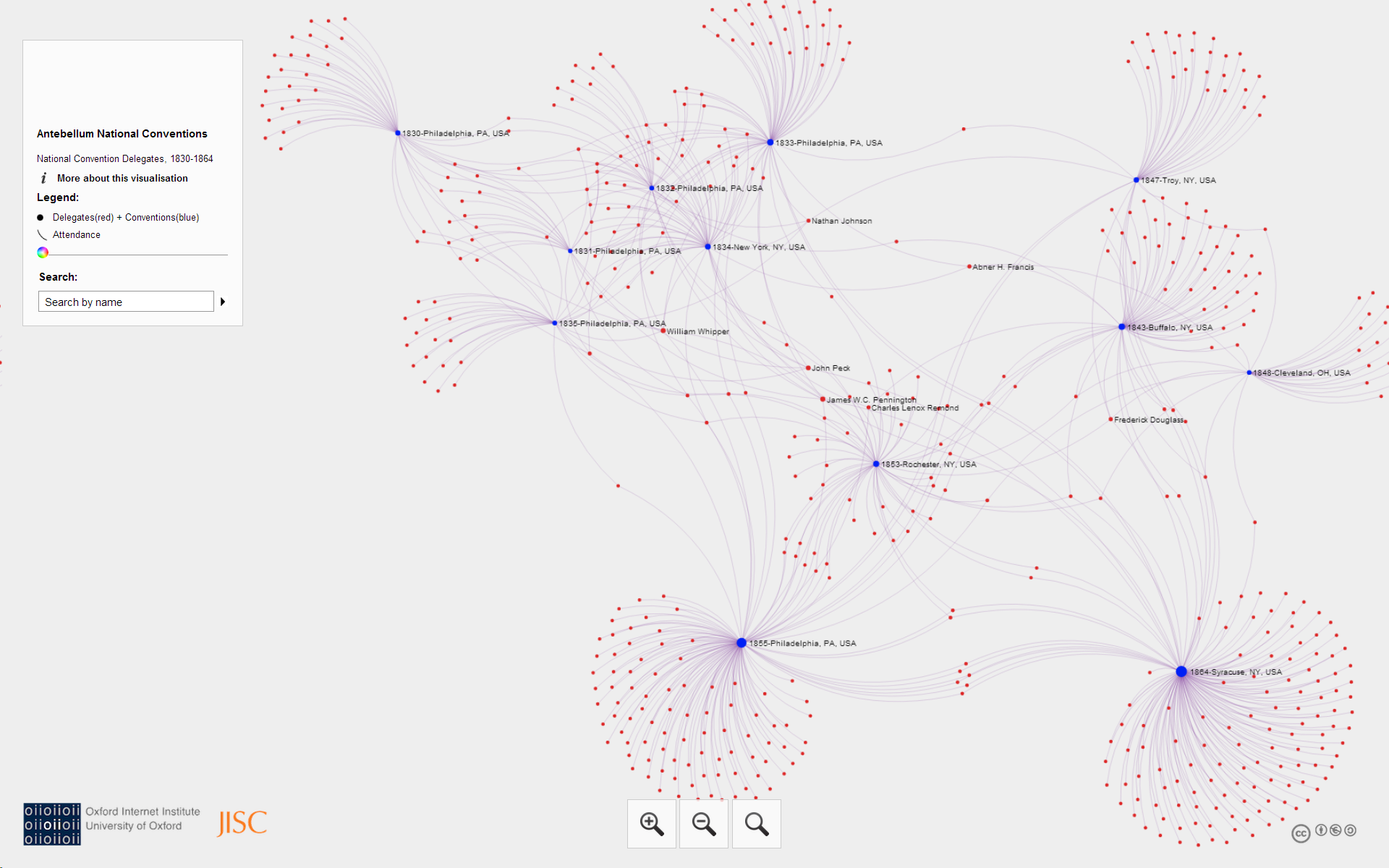

While we account for the richness of individual and lived experiences, the database allows us to ask larger questions about the social dynamics that emerged in the conventions. Even seemingly basic information—convention dates and delegates’ residences—enables us to ask wide-ranging and complex questions. Can we perceive patterns of the mobility of African American leaders throughout the nineteenth century? What kinds of communities emerged in the conventions as delegates attended meetings together, served on committees together, and co-wrote reports and addresses? Did certain unheralded individuals help bridge dispersed communities? Figure 2 is a prototype that visualizes the antebellum national conventions (blue dots) and delegates (red dots). While we should resist the temptation to draw any final conclusions from such graphs, these digital tools enable us to raise these broader questions that, in turn, invite many more specific questions that return us to the minutes and the archives.

Or we might take up other networked perspectives, such as a graph (fig. 3) of the conventions as linked by shared delegates.

For example, figure 3 might prompt us to ask questions that spark further conversation and research. How do we explain some of these strong connections that do not correspond to geography or reach across professions, religious denominations, or even different historical periods? Frederick Douglass attended conventions across five decades—perhaps the longest of anyone—with some who had known Richard Allen and others who would know W. E. B. Du Bois. Or, to take a broader example, we might study the links between 1830s and 1840s Pennsylvania state conventions, 1850s California state conventions, and Reconstruction-era national conventions in the South to glimpse a pattern of mobility for some African Americans in the nineteenth century. The entanglement of conventions and Black periodicals stands out as another arena of exciting opportunities for continued archival research guided by social network analysis. These questions are only a modest sample of the many ways that approaching the conventions as a source of historical, if fragmented, data can spark new conversations around opportunities for archival research in the years to come.

Next Collective Steps

Our process of transcribing and exploring the minutes has been shaped by the public and collaborative nature of the nineteenth-century Colored Conventions. We seek to build networked learning communities at each step that include and highlight the contributions of women and people of color. Looking ahead, we can only hope to contribute to a growing conversation about the dearth of diversity in the digital humanities by continuing to build partnerships that push us to explore the history of the Colored Conventions in evolving ways. As we look next to collaborative annotated editions of the conventions, new curriculum for college and church groups, and formal academic articles and books, there is much work to be done and plenty of room for new partners.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Jim Casey, a co-coordinator of the Colored Conventions Project, is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Delaware. He is writing a dissertation on the evolution of editorship in mass-market and African American periodicals during the mid-nineteenth century. He will also co-edit the collection Colored Conventions in the Nineteenth Century and the Digital Age.