Cross-Stitched History: Artistry and ambition in Christina Arcularius’s Tree of Knowledge sampler

In March 1792, fifteen-year-old Christina Arcularius put the finishing touches on her Tree of Knowledge sampler, a precocious display of needlework prowess and genteel accomplishment. Celebrated by decorative arts scholars as one of the most ambitious examples of New York’s Biblical sampler style, Christina’s needlework picture has been published and periodically exhibited in recent years. Nevertheless, her life and the circumstances surrounding the sampler’s creation have remained largely obscure. In 2003, Christina’s masterpiece was featured in the New-York Historical Society’s exhibition “Home Sewn: Three Centuries of Stitching History” as one of many hand-stitched items mined for the stories they could tell about their individual makers and the milieu in which they were produced. Considered in a broad cultural context, Christina’s sampler yields rich insights into female education and cultural aspirations in federal-era New York.

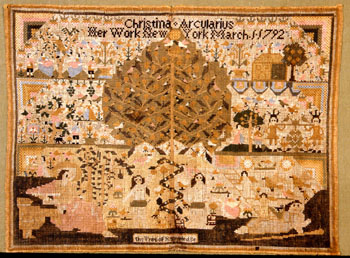

Christina’s delightful, if bewildering composition is brimming with Biblical and secular motifs organized in three tiers, all centered on a bird-filled Tree of Knowledge with a beguiling serpent coiled around its trunk. Worked mostly in cross-stitch using silk threads on a linen ground of twenty-four warps and wefts per inch, the 16-x-22-inch sampler contains more than 200,000 stitches. Created under the tutelage of a teacher who outlined the design, the sampler incorporates prescribed images intended to impart religious and moral values combined with creative flourishes from Christina’s own imagination. The Biblical imagery—the Tree of Knowledge, Adam and Eve, Jesus preparing to feed the multitude loaves and fishes, Jacob’s Ladder rising into heaven (lower band); the Spies of Canaan (middle band, right); and Zacchaeus in the tree (middle and top bands, left)—closely resembles that found on other New York samplers as well as on Dutch, German, and English prototypes. Christina industriously stitched her requisite Bible stories. But she also embellished them with numerous whimsical elements that were likely of her own creation. Over forty birds, symbolic of domesticity and marriage, flock to her Tree of Knowledge and perch throughout her Biblical land. Dogs, emblematic of faithfulness, stand beneath the trees. Many human figures—including at least four couples—populate the sampler, suggesting that the adolescent Christina may have been somewhat distracted by ruminations on courtship and love. The single building in the upper right, representing a church, house, or school, is illustrative of the comfortable intermingling of religious and secular instruction that pervades this sampler and also characterized elementary education in 1790s New York.

Christina’s Tree of Knowledge sampler is one of the finest extant examples from a group of Biblical samplers produced in the colony and later state of New York between the 1740s and the 1830s. These elusive embroideries, as yet not linked to any specific teacher or school, are thought to have originated in one of the elite French girls’ schools in New Rochelle, New York. Christina’s picture bears all the hallmarks of New York Biblical samplers: a solid ground worked in cross-stitch, with some decorative borders in Queen’s stitch; a profusion of Biblical motifs; and division into horizontal bands. The plethora of Biblical motifs seems to suggest that these samplers were produced in the context of religious instruction, and Christina did indeed come from a devout family of Lutherans-turned-Methodists. However, extant samplers reveal that the girls who stitched these exercises came from a range of Protestant religions, including Dutch Reform, Episcopal, Presbyterian, Lutheran, and Methodist. In addition, the Biblical motifs are linked to a long tradition of such imagery in European schoolgirl samplers, particularly those originating in Holland and northern Germany. Christina’s sampler is less significant as an artifact of religious instruction than as a document of the values and aspirations of the Arcularius family, particularly those of her father, Philip Arcularius.

Born in Marburg, Germany, around 1748, Philip Jacob Arcularius immigrated to New York prior to the Revolution and engaged in the baking business with his brothers. According to family legend, Arcularius volunteered to supply the city’s soldiers with bread during the Revolutionary War. By the 1790s he had left the baker’s trade to become a tanner and evidently prospered as a master artisan. Philip married Elizabeth Grim in New York City’s Lutheran Church in 1775, and the couple settled into a home on Frankfort Street. There they became parents to eleven children, seven of whom survived to adulthood. Christina, the eldest, was born in 1777.

Christina undoubtedly executed her sampler while attending a New York City school, likely within walking distance from her parents’ home in the city’s North Ward. In 1790s Gotham, most children were educated within an informal system of “pay schools” presided over by independent schoolmasters and schoolmistresses. For the average price of sixteen shillings or two dollars a quarter, students received instruction in reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, and morality. These schools generally enrolled both sexes, though boys typically outnumbered girls two to one. Unfortunately no documentation of Christina’s education survives, but we know that Christina’s siblings attended coeducational pay schools in lower Manhattan, where they mingled with children from a wide range of economic and religious backgrounds. In January 1803, Philip Arcularius paid Widow Catherine Mott of William Street two pounds for three quarters of teaching, as well as an additional sixteen shillings toward wood to heat the schoolroom. Ten months later, he again paid an installment for wood. Though the bill provides no specific details suggesting the focus of Widow Mott’s instruction (such as a charge for silk thread), it is possible that she taught needlework to girls in her care, including Christina’s younger sisters Margaret and Maria.

Bills also reveal that the Arcularius boys and girls received at least some of their education together. Schoolmaster Samuel Rudd charged Arcularius four dollars in August 1805 for the quarterly tuition of Margaret, two dollars for half a quarter’s tuition for Peter, and 37 1/2 cents for ink and quills. Rudd, whose schoolroom was located at 18 George Street, had been teaching in the city since the 1790s. His income of 200 pounds for the 1795-96 school year placed him among the city’s highest paid schoolteachers. More telling details are known about the school that the younger Arcularius girls attended the following year. In July 1806, Philip Arcularius was billed $6 by Ephraim Conrad for “education of daughters,” and another 50 cents for ink and quills. Conrad ran a coeducational school at the back of 32 Nassau Street and counted Maria and Margaret Arcularius among his pupils. A broadside announcing the school exercises—an evening showcasing student talent, open to the public for the admission price of two shillings—records presentations by the Arcularius sisters. Maria, along with classmate Margaret Tonnelle, delivered a “Dialogue on good behaviour,” while Margaret, with Mary Alstine, presented a dialogue on female education. The program’s subjects ranged from religious to literary to patriotic, indicating that a broad spectrum of students—sons and daughters of grocers, tailors, and merchants alike—were receiving a solid liberal education, designed to outfit them as citizens of the young republic.

It is clear that Philip Arcularius valued education, sought out well-respected teachers for his children, and viewed their schooling as a ticket to securing a solid future. While the Arcularius sons were being prepared for apprenticeships that would launch their careers as master artisans or merchants, the daughters were being groomed as domestic matrons, capable of managing the household of a respectable middle-class family. Like other parents of his era, Arcularius educated Christina in genteel pursuits with the aspiration that she would marry well and lead a comfortable life. Philip Arcularius was himself prospering during these years, rising as a successful master artisan to mingle with the ranks of the city’s mercantile and cultural elite. He played an active role in the religious and civic life of New York, holding positions generally reserved for citizens of higher status. He was elected to the state’s General Assembly five times between 1798 and 1805, serving as a Democratic-Republican. At the local level, he served as assistant alderman for New York City’s Fifth Ward from 1796 to 1800. In 1805, the Common Council appointed Arcularius superintendent of the almshouse, a prominent post implying credentials worthy of public trust.

Philip Arcularius’s rising star peaked in late 1805, when he became embroiled in a scandal at the almshouse. By early 1806, he had been removed from his position in disgrace. The incident had occurred on November 27, 1805, when Omey Kirk, a free black woman in labor, presented herself at the almshouse and was turned away for not having the required permit from a magistrate. She subsequently gave birth to a mulatto boy in a nearby yard and abandoned the baby there. Kirk was later discovered and committed to Bridewell Prison for abandoning her infant. William Coleman, Federalist editor of the New-York Evening Post, published an account of the incident in his paper two days later, laying the blame at the hands of the almshouse superintendent. Despite Arcularius’s protests that he was unaware of her condition, Coleman effectively destroyed his reputation. Two months later the Common Council passed a resolution removing him from his position as almshouse superintendent. Arcularius never recovered from the humiliation. After the incident, he never again held a publicly elected position.

Considered within this rich context, Christina’s Tree of Knowledge becomes a powerful artifact. As the eldest child of immigrant parents, Christina embodied the hopes of a family striving to make its mark in a new country and play an active role in the formation of the young republic. As an adult, Christina is reported to have regaled her children with stories of the new nation’s early struggles and triumphs, and according to her daughter “never tired of telling what she had witnessed in old New York.” She recalled the dramatic British evacuation of New York in 1783, which she experienced as an eight-year-old, and witnessed George Washington’s inauguration as first president of the United States on the balcony of Federal Hall in 1789. She claimed to have vivid memories of the gallows, pillory, and whipping post that stood not far from her Frankfort Street home, recalling that “hanging day was a general holiday and schools were dismissed that the children might witness the horrible sight.” While primly stitching Eve’s fall from innocence on her canvas, Christina likely reflected on the brutal consequences suffered by those who succumbed to temptation in her everyday world. The sampler’s cross-stitched Eden conveys a bountiful optimism that parallels the Arcularius family’s rising status in 1792; however, Christina’s towering Tree of Knowledge, weighty with moralistic overtones and avian overabundance, suggests potential threats to Christina’s imagined idyll and domestic reality. One wonders whether Christina sensed the dangers that lay ahead as her father ascended New York’s perilous social ladder.

At age twenty-two Christina married New York City grocer Samuel Barker Harper and assumed the conventional domestic role of wife and mother, likely fulfilling the expectations of her ambitious father. On the occasion of her marriage in 1799, Philip Arcularius presented her with a collection of silver dollars that soon thereafter were melted down to make a fashionable silver tea set. Following their marriage, Christina and Samuel Harper set up their own household and raised five children to adulthood.

The couple had formal portraits painted of themselves around 1830: Christina was portrayed as a conservatively attired matron with searching brown eyes, an intent gaze, and a face set with determination. As Harper’s grocery business prospered, the family moved to ever more fashionable neighborhoods, eventually building their own home on St. Mark’s Place in 1842. The Harper and Arcularius families, both devoutly Methodist, became progressively intertwined as Christina’s younger sister Maria married Samuel’s nephew James Harper (later the mayor of New York City), and Samuel took on Christina’s brother Andrew as a business partner.

Christina’s Tree of Knowledge sampler probably remained in her home on St. Mark’s Place until her death in 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. It likely passed to her eldest daughter Amanda, whose own New York sampler of c. 1815 (which survives at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) speaks to the continuing tradition of educating Arcularius/Harper daughters in needlework. Christina’s grandchildren recognized a perfect home for her needlework picture in the vast collection of European and American samplers gathered by Mrs. Lathrop C. Harper (Mabel Herbert Urner), wife of Christina’s grandson. Mrs. Harper collected over six hundred examples by 1924 and more than eight hundred by the time of her death in 1957, probably the largest sampler collection in America, mostly gathered on annual buying sprees in Europe. An article on her collection in the March 1924 issue of The House Beautiful illustrates some of these treasures displayed in her gracious home amidst Harper family heirlooms. Fittingly, the oil portrait of Christina Arcularius Harper hangs in one corner of the drawing room, surrounded by a sea of exquisitely crafted samplers.

Mrs. Harper bequeathed her extensive collection of samplers to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1957. Interestingly, she singled out only one piece from her vast holdings—Christina’s Tree of Knowledge sampler—for donation to the New-York Historical Society, recognizing its greater value as a historical document than as a work of art. Presumably she realized that Christina’s sampler represents more than a schoolgirl exercise or a display of needlework talent: it is a potent cultural artifact that opens a window into young women’s education and the social fabric of 1790s New York.

Further Reading:

Primary documents in the library of the New-York Historical Society provided the starting point for unearthing Christina’s personal and family history. The extensive Lathrop Colgate Harper family papers—including correspondence, diaries, scrapbooks, and financial records—span four generations of this quintessential New York City family. Numerous photographs of Christina’s children, grandchildren, and their residences can be found in the Lathrop C. and Mabel H. Urner Harper photograph collection. A printed pamphlet, “A Faithful Report of the Trial of the Cause of Philip I. Arcularius, and William Coleman, Gent.,” provides fascinating details about the almshouse incident that disgraced the Arcularius family.

The Biblical samplers of colonial and federal New York are analyzed in the second volume of Betty Ring’s major work, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850 (New York, 1993), to date the only significant published analysis of this important group. For the social history of American needlework, see Susan Burrows Swan’s Plain & Fancy: American Women and Their Needlework, 1700-1850 (New York, 1977). The inspiration to weave a story from one seemingly ordinary needlework picture is owed to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York, 2001).

The cultural environment of Christina’s New York was reconstructed with the aid of city directories, census records, and the Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, as well as Carl F. Kaestle, The Evolution of an Urban School System: New York City, 1750-1850 (Cambridge, Mass., 1973), Paul A. Gilje and Howard B. Rock, eds. Keepers of the Revolution: New Yorkers at Work in the Early Republic (Ithaca, 1992), and Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City & the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788-1850 (New York, 1984). Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace’s comprehensive Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York, 1999) offers a richly detailed account of everyday life in 1790s New York City.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.4 (July, 2004).

Margaret K. Hofer is curator of decorative arts at the New-York Historical Society, where she organized the exhibition “Home Sewn: Three Centuries of Stitching History,” on view from November 18, 2003, to April 18, 2004. She is the author of The Games We Played: The Golden Age of Board and Table Games (New York, 2003) and co-author of Seat of Empire (New York, 2002).