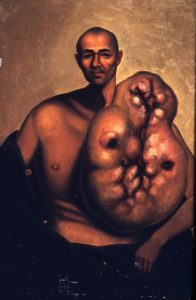

In another case that Parker likely presented to his audience, that of Woo Kinshing (fig. 2), the tumor appears as the patient’s prop, as a musician might pose with his cello, as the eye shuttles between these two ways of seeing. Parker describes Woo Kinshing as having a ten-year-old tumor that had “attained a very great magnitude resembling in figure a tenor viol.” Because the shape and size of Woo Kinshing’s tumor resembles a familiar nonpathological object, a “tenor viol” as Parker calls it, Lam Qua’s image elicits a further curiosity. In fact, Parker informs us that Woo Kinshing would rest on his growth like a mattress, referring to the tumor as the patient’s “old companion” and calling Woo Kinshing at several points “the old gentleman” (though he was only forty-nine). The indirection or redirection of the pathological gaze toward some other object produces the ludicrous effect, reinforcing the tumor’s status as curiosity. While deformities and pathologies have always made for objects of curiosity, tumors add to this a general absence of function; they seem to serve no purpose but to deform. The effect of these paintings is to force upon the viewer the experience of tumors, in and of themselves, as curiosities. As masses of new tissue growth, independent of surrounding structures having no apparent physiological function but to divert the resources of the body, all tumors call into question the purpose of their existence. But the very massiveness of these tumors, sometimes rivaling the size of their host, makes their seeming purposelessness all the more obvious. They seem to be giant physical manifestations of a kind of extravagance, or excessiveness, a breaking out of boundaries, form, and structure. In this context, Parker’s extirpations of them become a restoration of the self from an enormous irrelevancy. If curiosities are curious because, in Barbara M. Benedict’s words, they “have no function but to be looked at,” then Lam Qua’s pictures of giant tumors elicit curiosity in a double sense. They are at once formless and functionless.

The response to these portraits illustrates not merely the collision of sensibilities of Boston and Canton in the 1840s, nor the domination of the western gaze of science, but elements of both. It also captures a collision between the rationales for looking itself. One might look with the Boston Medical Association out of medical, missionary, or cultural motives and one might look out of an impulse that seems to counter these, to occur at the threshold of culture, before one makes up reasons to justify looking–staggering, naked, curiosity. They evoke the power of wonder, as Stephen Greenblatt has described it, “to stop the viewer in his or her tracks.” The evidence of Parker’s audience giving voice to both kinds of looking simultaneously indicates the way collectively shared curiosities or exotics enter culture attached and in resistance to their artifactual, epistemological, and moral raison d’être. Like a patient recovering from back surgery who sings the praises and pleasures of doctor-prescribed opiates, the members of the Boston Medical Association expressed without controversy or censure the pleasure of curiosity because of a moral and scientific rationale that legitimated their interest. This combination of the moral and the curious was a typical rhetorical strategy of what one might call “curiosity management” in the antebellum United States.

For some time, cultural historians have been pointing to the 1840s, the very moment of Parker’s tour, as a time when Americans began to participate on a mass scale in the business of curiosity. Through his American Museum in New York City and its notorious attractions (e.g. “The Feejee Mermaid”), P.T. Barnum (and to some extent before him, Charles Willson Peale) pioneered the exploitation of curiosity for an incipient mass culture. In his museum, where Barnum would display all kinds of curiosities alongside natural history exhibits and temperance dramas, the educational and moral were always invoked to contain the prurience and profitability of the curiosity. “My plan,” Barnum claimed, “is to introduce into the lecture room highly moral and instructive domestic dramas, written expressly for my establishment and so constructed as to please and edify while they possess a powerful reformatory tendency.” Even Barnum’s “operational aesthetic” as Neil Harris labeled the way that Barnum used frauds and “humbugs” to play with his audience’s desire “to debate the issue of falsity, to discover how deception had been practiced,” helps celebrate curiosity as a pleasurable search for truth. In a less self-conscious but analogous way, Parker’s collection of patient portraits piqued the curiosity of his Boston audience. While Parker was certainly no Barnum, the overt religious and medical context exculpated the more inchoate expressions of human interest that the paintings excited. Though Parker saw his task as one of extirpation, containment, and conversion, by displaying the paintings he allowed for a vicarious encounter with Chinese bodies that inevitably promoted a kind of unself-conscious voyeurism. As Barnum deployed curiosity in the interest of a kind of democratic epistemology, so Parker, perhaps guilelessly, called on curiosity to promote the conversion of China.

In the 1840s, one could find in the U.S. cities medical museums and “Museums of Anatomy” that catered to men, displaying pathologies, genitalia, embryology, and an array of unusual conditions. Frequently these were places of mild sexual titillation under the guise of anatomical and sexual education (similar to the way boys of a bygone generation would turn to the pages of National Geographic for pictures of naked women). According to Andrea Stulman Dennett, marginal doctors peddling cures for gonorrhea and syphilis and tracts inveighing against the evils of “self-abuse” often ran these establishments. In these dime museums, curiosity and cure were wedded: those customers who might be susceptible to the sexual come-ons of an anatomical museum might also be in need of a cure for an unmentionable itch and feel guilty enough to buy an antimasturbation tract. In a much more muted way, Parker’s use of Lam Qua’s paintings functioned as examples of missionary cures and curiosities. The enormity of the tumors seemed to represent the enormity of the medical problems and missionary challenges of China. The imaginations of “a few good men,” as the Marines advertisement has it, might be fired by the sight of Lam Qua’s portraits, inspiring them to sign up with Parker for a missionary tour of duty. The curiosity as sign of exotic adventure was becoming more common in this era. In fact, the OED informs us that the 1840s were the years in which “curio” emerged as an abbreviation of the word “curiosity” referring “more particularly to articles of this kind from China, Japan, and the Far East.” The first usage the OED offers comes from an early scene in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851) in which Queequeg is described as one who “bought up a lot of ‘balmed New Zealand heads (great curios, you know), and he’s sold all on ’em but one.” While Parker was not peddling shrunken heads, he had returned from China with images that took on a similar outlandishness.

In a sense, the cultural status of the portrait of Lew Akin and the other pictures that Parker showed in Boston in 1841 have not changed much in the 160-odd years since that first exhibition. In early 1838, Parker planned to donate the painting to an “Anatomical Museum of the Medical Missionary Society in China,” the recently formed body that sought to institutionalize the medical missionary approach exemplified by Parker and his English and American colleagues, but that museum never came about. Parker did however deposit a set of portraits at Guy’s Hospital in London–which may have been an expression of the original plan–where, according to Parker’s English colleague, William Lockhart, they continued to “excite the surprise of students and visitors.”

Surprise and curiosity were reactions attendant but not central to the paintings’ purported purpose, and it is fitting that they continue to occupy a kind of limbo, objects of medical and cultural curiosity, paintings of historical but not exactly aesthetic interest. An exhibit of the Yale collection has only been mounted once, in 1992. Inside one of the cabinets containing the paintings a bit of undated doggerel reads:

Peter Parker’s pickled paintings Cause of nausea, chills & faintings; Peter Parker’s putrid portraits, Cause of ladies’ loosened corsets; Peter Parker’s purple patients, Causing some to upchuck rations. Peter Parker’s priceless pictures: Goiters, fractures, strains and strictures. Peter Parker’s pics prepare you For the ills that flesh is heir to.

Susan Stewart’s On Longing, and James Clifford’s essay “On Collecting Art and Culture” delineate the processes by which western cultures have transformed inchoate fascination and curiosity about rare and exotic objects into the “rule-governed” taxonomies and classifications of the museum. In a sense the presence of this comic verse and the paintings’ lack of classification indicate the extent to which they remain “curiosities,” uncontrolled growths like the tumors they present, artifacts that startle tact and science rather than promote scientific and cultural order.

Perhaps ultimately, the paintings have remained curiosities because of the profoundly personal and unresolved motives out of which Parker commissioned them. On a psychological level, the paintings must have served as a form of compensation for the doctor who took no fees and found surgery a religious ordeal, a way of taking and maintaining possession of his patients. “God has signally smiled upon efforts to benefit the body,” Parker noted in his journal for March 1843. “On Wednesday, the fifteenth, [I] removed with success a tumor from a little above the groin of a young man twenty-five. The situation and the bloody character of the operation gave me marked solicitude for the result, but of the propriety of attempting to remove it there was no doubt. It was from the bended knee in one room that I went to take the knife in another. God heard the petition offered.”

From chapel to table, from prayer to cutting, the doctor moved, and he saw surgical outcomes (at least the positive ones) in providential terms. Many of the paintings were, indirectly, the tokens and mementos of answered prayers. While visiting Guy’s in 1841 in the company of two well-respected London surgeons, Parker came across the set of paintings he had deposited there. His journal tellingly records: “Found a collection of my patients in the Museum.” When Parker learned that the surgeons were unaware that these patients had been operated on, he informed them, “Yes they have, all of them & with success.” For Parker, the paintings became a symbolic means of collecting and transporting his patients. Thus, when the English surgeons mistakenly presumed that they were merely specimens of gross pathology, Parker was quick to correct them, to insert his own role as surgeon into their meaning. But without the doctor present to explain and contain their cures and significance, without a scholarly apparatus to regulate our understanding, the pathological tension of Lam Qua’s likenesses and representations continues to exhibit its curiosity.

Further Reading: For general accounts of Parker and Lam Qua, see Edward Gulick, Peter Parker and the Opening of China (Cambridge, Mass., 1973); Jonathan D. Spence, To Change China: Western Advisers in China (New York, 1969); Peter Josyph, From Yale to Canton: The Transcultural Challenge of Lam Qua and Peter Parker [exhibition catalogue] (Smithtown, N.Y., 1992); and Larissa Heinrich, “Handmaids to the Gospel: Lam Qua’s Medical Portraiture,” in Tokens of Exchange: The Problem of Translation in Global Circulations, ed. Lydia H. Liu (Durham, N.C., 1999). Accounts of Parker’s visit to Boston can be found in Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 24 (April 21, 1841) and Papers Relative to Hospitals in China (Boston, 1841). Parker’s case histories for the paintings discussed above can be found in The Chinese Repository (Canton) May 1837. On Barnum, Neil Harris, Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum (Chicago, 1973). On collection, see Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore, 1984); James Clifford, “On Collecting Art and Culture” in The Cultural Studies Reader, ed. Simon During (London, 1993). On curiosity, Stephen Greenblatt, “Resonance and Wonder” in Exhibiting Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, eds. Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine (Washington, D.C., 1991); and Barbara M. Benedict, Curiosity: a Cultural History of Early Modern Inquiry (Chicago, 2001). On the anatomical museum, see Andrea Stulman Dennett, Weird and Wonderful: The Dime Museum in America (New York, 1997).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.2 (January, 2004).

Stephen Rachman teaches English and American studies at Michigan State University.