Dark Histories of Death

John Clark was out on a surveying expedition in western New Mexico Territory on May 7, 1865, when he heard. Gold miners heading the other way told him that President Lincoln had been assassinated. It was horrible and incredible news. And the murderer was Edwin Booth Jr., the actor! (John Wilkes would have been devastated to know that his work had been so misattributed). Clark was devastated. Abraham Lincoln was not only the revered president; he was an old friend from Illinois and the reason that Clark was out here in the first place. Lincoln had appointed him surveyor-general of New Mexico Territory in the spring of 1861.

For the next two days Clark made his way eastward toward Santa Fe, stunned. “How long OH! How long will thou afflict & chastise this nation, oh God!” he wrote in his diary. Lincoln “seemed to have been specially set apart and dedicated to the great work of preserving & reforming the nation.” Why had this happened? Perhaps the northern people had “trusted more in him than in Him who directed & controlled him & this is our punishment.” Clark hoped that there was some mistake; but when he arrived at Fort Wingate almost a week later, the papers confirmed the news. “His loss at this time,” Clark wrote, “is irreparable.”

After he arrived back in Santa Fe, Clark continued to mourn his friend, and worried about the nation’s future. But soon his mind turned to other things. He had to organize his office after his time away and write up the report of his journey into New Mexico’s gold country. After his entry from Fort Wingate on May 13, John Clark made no more mention of Lincoln—or his death—in his diary.

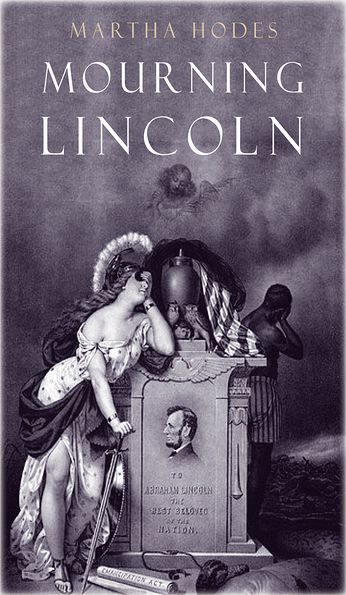

The ways that John Clark heard about, disbelieved, misunderstood, reckoned with, wrote about, and then moved on from Lincoln’s assassination were commensurate with the responses of Union supporters all over the nation, as Martha Hodes tracks them in her riveting new book, Mourning Lincoln. This group of Lincoln’s mourners produced voluminous personal records—diaries and letters, in particular—detailing their reactions to Lincoln’s death and funeral in April 1865. So many records in fact, Hodes argues, that Union supporters created an “illusion of collective grief,” a perception that the entire nation—North and South, black and white—was unified in its response to the assassination. Hodes suspected that this could not possibly be true, and in Mourning Lincoln she uncovers a broad range of reactions to the Union president’s death that cut across regional and racial lines. “This end-of-the-war moment,” she writes, “was less a time of unity and closure” and more a time of violent passions and disagreements (10).

In chapters that are both thematic and chronological, Hodes keeps a tight focus on individual acts of mourning (or celebration)—talking to neighbors, putting up bunting, gathering together at Lincoln’s funeral or at the railroad track as his funeral train passed, going to church, writing accounts—in the weeks after Lincoln’s assassination. She begins each chapter with an examination of the emotions and activities of three “protagonists”: Sarah and Albert Browne, white abolitionists from Salem, Mass., who are Union supporters (“Lincoln’s mourners”); and Rodney Dorman, a white Confederate lawyer in Florida who is one of “Lincoln’s antagonists.” This is a useful narrative tool, as it provides readers with continuous threads that bind the entire book together. These three people eloquently and vociferously express a range of reactions—shock, fury, sorrow, confusion, religious doubt, resentment, anger, glee—that, for Hodes, confirm a broader pattern of responses across the nation. Those who identify as “Lincoln’s mourners” and “Lincoln’s antagonists” are mostly exactly who you suppose they might be, but Hodes does find significant disagreement within regions: not all Southerners were gleeful at the news, and not all Northerners grieved Lincoln’s loss.

Hodes makes her most important discoveries by examining the emotional upheaval that African Americans experienced in the wake of the assassination. This proved difficult to root out; as Hodes says in her “Note on Method,” the personal writings of African Americans from this period are scant. She therefore turned to black newspapers and the records of whites who worked closely with blacks to try and make these “submerged voices” audible (276). Exuberant but also wary in the last months of the war, African Americans on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line were troubled by the leniency toward Confederates that Lincoln’s second inaugural seemed to suggest, but were then buoyed by his final speech advocating black citizenship rights. Initially they were hopeful that Andrew Johnson would prove an ally; his first few months in office dashed those hopes. They celebrated the justice that the deaths of Booth and his conspirators seemed to bring. They fought for their own rights, helped by their white Republican allies in Congress. But despite some gains, African Americans looked to their futures with trepidation and wondered what could have been. In the end, Hodes argues, Lincoln’s assassination “was the first volley in the war that came after Appomattox—a war on black freedom and equality” (274).

Hodes conveys all of her points in compelling prose, using parenthetical asides and staccato sentences to create drama in the narrative. She also makes some pleasing analytical and methodological moves, calling attention to writing itself as an act of mourning and persuasively close-reading diary and letter writers’ emphatic punctuation: exclamation points, question marks, underlines, inked borders.

She also inserts a somewhat unusual narrative structure into Mourning Lincoln: short (two-three-page) snippets of writing between chapters, in which she considers specific metaphors or images of mourning or celebration. I was initially excited to encounter these “interludes”—I yearn for history books that diverge from the usual Intro-Five Chapter-Conclusion structure. I was disappointed, however. The interludes serve only to interrupt the narrative flow of the chapters (for which Hodes has written lovely transitions from one to the next) and to silo some potentially revealing evidence from the larger arguments that the chapters convey. Strangely, Hodes makes no mention of these interludes or their purpose in her preface, and so they become merely narrative curiosities, initially interesting but ultimately distracting.

In the end, however, Mourning Lincoln helps us to understand the immediate aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination and its multiple and complex meanings for all Americans. It is a dark history of the president’s death, revealing the rancor and emotional volatility that shaped individual lives across the nation at this moment. Grief over the president’s death was not universal—neither were visions of the future of the United States, or African American rights. And that grief was not long lasting. Like John Clark, most Americans had more pressing concerns and they recovered from the shock within a few weeks. Mourning Lincoln reveals all of these processes to us, a useful reminder that national tragedies can violently alienate people from one another in the moment, and then fade just as quickly from our collective consciousness.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3.5 (July, 2016).

Megan Kate Nelson is a writer, historian, and cultural critic based in Lincoln, Massachusetts. She is the author of Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (2012) and Trembling Earth: A Cultural History of the Okefenokee Swamp (2005)—and is working on a third book, Path of the Dead Man: How the West was Won—and Lost—during the American Civil War.