The son of his master and an enslaved woman, Roper was sold as a young child and transferred between several masters, including Mr. Gooch, whose cruelty toward slaves was unparalleled. Unable to break his will, Gooch eventually sold Roper again. After several more years of moving between new masters, Roper finally escaped by passing as a ship steward on a schooner bound for New England and then another to Liverpool. A description of a life suspended between blackness and whiteness, childhood and adulthood, slavery and freedom, Roper’s account of his life always turns on the appalling cruelties that were the one constant of his identity, relating them through a characteristically straightforward style. For instance, the Narrative opens with an incident that took place in Roper’s infancy when his mistress attempted “to murder me with her knife and club.” Despite recalling his own early brush with death, Roper offers no accompanying discussion of his or his family’s feelings about the incident.

Roper began telling his story, and perfecting his rhetorical style, on the abolitionist lecture circuit in England in 1836, having left New York six months earlier. Brief speeches by “Mr. M. Roper stating some facts” enumerated the forms of violence inflicted upon him and other enslaved people. For the rest of his life, Roper sold the details of his past, giving endless lectures and stumping for the continued reprinting of his book. From the moment it first appeared, Roper’s Narrative was a commercial success, going through ten editions between 1837 and 1856. In 1844 Roper claimed “twenty-five thousand English, and five thousand Welsh copies are now in circulation.”

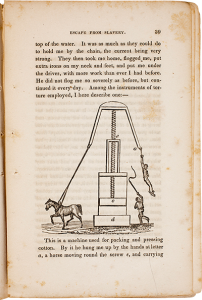

A striking intrusion into the text, the image of Roper’s torture illustrates the boundlessness of his master’s cruelty. Originally designed as a machine used to efficiently press raw cotton into manageable bales, Gooch repurposed the contraption so that its spinning mechanism would carry a suspended Roper around in circles. Repetitive in its infliction of violence, the cotton screw resembled Roper’s life as a slave whose failed escapes continually returned him to slavery and to ever more horrible kinds of abuse. As Marcus Wood has argued, the “cyclical nature” of the machine underscores “the tedious repetition of Roper’s experience of bondage.” Explaining how the newly adapted machine functioned, Roper identified its various components and their uses: “By it, he hung me up by the hands at letter a, a horse moving round the screw e, and carrying it up and down, and pressing the block c into the box d, into which the cotton is put. At this time he hung me up for a quarter of an hour. I was carried up ten feet from the ground, when Mr. Gooch asked me if I was tired. He then let me rest for five minutes, then carried me round again, after which he let me down and put me into the box d, and shut me down in it for about ten minutes. After this torture, I stayed with him several months, and did my work very well.” Subjected to a press and then packed into a box, Roper is nearly transformed from human being to processed commodity by Gooch’s ghastly device. But Roper’s account of the ordeal shows that slave owners like Gooch fundamentally misunderstood the difference between goods and people. No matter how much the slave system insisted that its business was purely one of commodities, the horrific reality of the “processing” needed to make people resemble salable goods was evidence of the absolute absurdity of such claims.

The Narrative would seem to have been in keeping with the endeavors of Roper’s publisher, the Quaker firm Darton, Harvey, and Darton. The London firm specialized in children’s literature and antislavery material, forms that often overlapped in works containing pictorial poems and alphabetic verses. While not a pedagogical tool, the Narrative‘s format reflects the conventions of a short-lived but significant genre of antislavery children’s literature that emerged in the United States in the 1830s. The Slave’s Friend, for instance, appeared monthly between 1836 and 1839 in New York, its tiny sixteen-page issues designed to spread the American Anti-Slavery Society’s message that young people should learn to “love the poor slaves.” Roper’s 106-page Narrative—short, illustrated, written by a teenager about the realities of childhood under a system of unbelievable abuse, and printed by a children’s literature publishing house—urged white children to imagine, for just a moment, what it was like to live a slave’s life.

But while the overall format of Roper’s Narrative resembles children’s antislavery literature, taken on its own terms the engraving showing Roper’s punishment more readily suggests another contemporary genre—the patent application. By the 1830s, dissatisfaction with United States patent laws had reached a tipping point, culminating in a widely publicized major restructuring of the patent system in July 1836. Roper turned the patent application inside out, copying its attention to mechanical parts, novelty, and efficiency in order to mock a national system that, if taken to its logical conclusion, could accept a torture device as an example of American innovation. Much of Roper’s critique relies on the way the diagram directs viewers to read the text around it as a key to its component parts. Yet the missing letter “b” in both image and text implies that the machine is absent a crucial element. Does “b” refer to Roper or to the man who whips him? If “b” represents Roper, is the letter missing because Roper has run away and is no longer part of the system? Roper’s diagram reminds readers that human beings, the one thing on which slavery invariably depended, would never be the mechanical parts that such a system demanded.

As interest in the Narrative increased, Roper and his publishers produced new editions that still contained the diagram, but that were also illustrated by elaborate, captioned scenes from Roper’s life. These engravings capitalized on the growing popularity of the fugitive slave narrative and its connections to sentimental reading culture, inviting readers to see Roper as an identifiable and relatable victim. But even though the later graphic additions overtly urged an affective response, first edition readers nevertheless seem to have formed embodied, emotional connections to the Narrative through its striking image. To take one example, the illustration in the 1837 edition held at the Library Company of Philadelphia shows evidence of countless thumbs, their owners having paused to consider Roper’s experiences through the childlike act of touching the unsettling and defamiliarizing diagram of Roper’s childhood torture.

Further reading

Most discussions of Roper’s Narrative are unsurprisingly devoted to its shocking portrayals of violence. Its publication history and word/image relations have received far less attention; illustrations in the later editions are especially in need of further research. The most comprehensive discussion of the images in Roper’s Narrative is in Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America (New York, 2000). For studies that position the narrative and the cotton screw illustration within a history of African-American and antislavery writing, see William L. Andrews, To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760-1865 (Champaign, Ill., 1988), William L. Andrews, et al., eds., North Carolina Slave Narratives: The Lives of Moses Roper, Lunsford Lane, Moses Grandy & Thomas H. Jones (Chapel Hill, 2003), and Philip Lapsansky, “Afro-Americana: Moses Roper, at Home and Abroad,” The Library Company of Philadelphia 1996 Annual Report: 23-26. For information about Roper’s role as an antislavery lecturer, see C. Peter Ripley, et al., eds., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Vol. I: The British Isles, 1830-1865 (Chapel Hill, 1992).

This article originally appeared in issue 13.3 (Spring, 2013).

Megan Walsh is an assistant professor of English at St. Bonaventure University. She is the co-editor of Frank J. Webb’s The Garies and Their Friends, forthcoming from Broadview Press, and is currently completing a book manuscript titled “A Nation in Sight: Book Illustration and Early American Literature.”