Digging Up History: How Photo-Flo and elbow grease are saving New England’s historic cemeteries

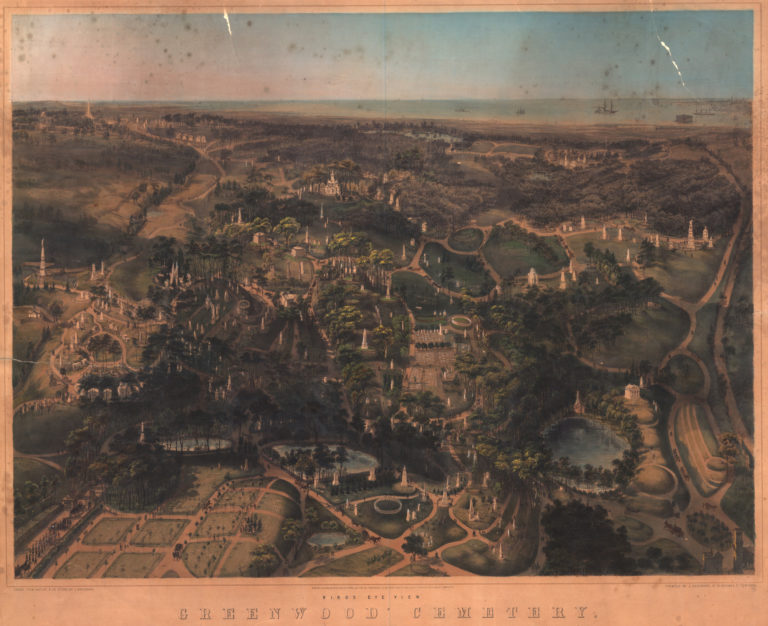

“Poor George,” we grunted as we looked down to survey the damage. George was hurting. His face was flat on the ground and, while ants and shoots of uncut grass explored ways to migrate around his heavy, white body, layers of mold and errant pine needles concentrated in the decaying crevices on his back. Laboring just to pick him up, we hoisted George onto a pair of wooden 2-by-4s nearby, the damp ground almost groaning from the unexpected weight it now had to bear. As my colleague and I stood over George, contemplating the best way to clean him up, it occurred to us that we were using the word him to describe what was really an it. “George” was not an actual person, but a gravestone that memorialized a person’s life and mourned his death. And yet we spoke of his stone’s dilapidated condition as if it were a human being, someone in need of attention and care. George L. McIntire’s nineteenth-century marble marker had accumulated years of organic buildup, the weather had worn down much of its inscription, and it had tumbled forward and off its marble base, either from a natural incident or a malicious push. The stone, which rests in Wellesley, Massachusetts’ First Congregational Church’s cemetery, was, like many other stones beside it and throughout New England, in desperate need of repair (fig. 1).

Thousands of stones across New England share stories like George’s: although they were intended to honor and recall the dead, their decaying state (toppled over, broken, leaning, or just plain dirty) prohibits them from performing their designated function. Gravestones seem to be, like the memories of the people they honor, eternally immutable, intransient reminders of the lives, loves, and losses of the past. Even the substance they’re made of is a metaphor for durability and permanence. And yet, as any resident of New England knows, soil moves, water erodes, tree limbs fall, frost heaves erupt, sun rays blister, roots expand, and mold advances. Constant attacks from weather, in addition to the mechanization of landscaping, conspire to destroy these stones as they once stood. Ironically, New England’s historic cemeteries are dying.

Fortunately, a handful of preservationists are laboring to safeguard the invaluable treasures within these early American cemeteries. Fannin-Lehner Preservation Consultants, my summer employer, is an award-winning company out of Concord, Massachusetts, that does just that. Although it is a small firm, it has taken on the ambitious task of restoring and repairing cemeteries throughout New England and beyond. And the company is not alone. Dozens of other people, from preservationists and historians to local townsfolk and eager volunteers, are energetically preserving these endangered markers from oblivion.

The public, and historians in particular, are intrigued by the physical process of preservation. As we work in Salem, Massachusetts, for example, visitors constantly inquire about what we’re doing there. “Are you digging up the witches?” younger kids (and a handful of adults) often ask. While the jokester in me wants to reply that we are rummaging for bones to include in a perfectly delectable “witch stew” (or something to that effect), the historian and responsible employee instead patiently explains the process of assessing, removing, cleaning, and resetting the gravestones that inhabit these holes. Assuring my spectators that I rarely dig more than two feet below grade helps set them at ease, even if I can’t resist occasionally pretending to strike a coffin. Although many observers are initially unsettled and disturbed, they frequently wind up inquisitive. How do you restore a gravestone? What if it is chipped? What’s that soapy stuff you use to remove the gunk?

I have to admit that, when I began preserving gravestones, I wondered about the darker, macabre impulses that gave me such an affinity for the work. And yet I never find it to be depressing. Instead, working in cemeteries has been surprisingly uplifting. There are few places more peaceful than a New England cemetery in the summertime, and as a historian, I relish playing a small part in this gargantuan effort to preserve these seemingly permanent but ultimately delicate examples of early American material culture.

So, how exactly does one preserve a gravestone? How would one go about fixing stones similar to poor “George”? The answer depends on the stone, and each type of stone has its own qualities, characteristics, and challenges. If you travel to any colonial cemetery (contemporaries would have referred to them as burying or burial grounds), you’re certain to find the most common material used in early American gravestones: slate (fig. 2). Dark and tall, slate stones are the easiest material with which to work. Although slate can chip and flake quite easily, the stones’ slenderness usually makes them lighter and relatively easy to maneuver (excepting the massive ones). Slate can be easy to clean, as it is generally smooth and resistant to the lichen and mold that accumulates easily on other stones. And yet, some slate stones still have ridges in their backs from their original quarrying, giving lichen and other organic material an ideal place to accumulate. Slate markers can be deceivingly hefty, for only 60 percent of any slate gravestone is actually exposed to the air. The other 40 percent is below grade, using simple physics to keep the stone straight. Imagine that: every time you see a slate gravestone in a colonial cemetery, you are looking at just more than half of its full size! The other half is buried beneath the surface, amidst the rocks, sand, roots, bricks, and other materials that may have migrated into the soil.

By the nineteenth century, thanks to improvements in transportation and technology and the expansion of the market, marble and granite began to eclipse slate as the cemetery stone of choice. These nineteenth-century stones are generally thicker and thus heavier and sturdier, so they are less inclined to lean than slate; their mass and large footprint generally keep them upright. And yet, they too can topple over and become victim to the changing landscape, frost heaves, and even vandalism. Granite, like marble, is crushingly heavy. Unlike slate stones, trying to remove a marble or granite stone by yourself will almost surely send you to the chiropractor, as such a stone can weigh hundreds of pounds. However, because nineteenth-century carvers usually cut them square, these stones are relatively easy to slide, grasp, and turn. They usually need to be rolled or pried out of their holes, and some of the heavier ones actually remain in these excavations during preservation. Over time, the components that hold marble together can disintegrate, especially in acidic environments (think acid rain). This makes the stone more porous, more vulnerable to organic penetration, and therefore more difficult to clean. In these cases, an hour or more of vigorous scrubbing is needed to really make a difference (notice George’s stone, for example, in fig. 1). Granite is generally smoother than marble, less porous, and therefore much easier to clean.

Whether the stones are slate, marble, or granite, the rehabilitation process is essentially the same. Smaller ones are removed from their holes and carefully placed on wooden 2-by-4s for cleaning, while larger ones remain and are leveled by simply shifting their bases until they are in line and level. Workers clean the stones with a healthy dose of Photo-Flo, a non-ionic and soapy liquid that is used to process film. It is strong but soft, and it helps attack the mold and lichen without bruising or flaking the stone. They also use standard brushes one might find in any store’s cleaning aisle, along with plastic scrapers, wood sticks, and even hard toothbrushes, which may be better suited to cleaning up the names, dates, and ornamental motifs inscribed on the stones than cleaning teeth and gums. The goal, of course, is to attack the dirt and organic material that has become encrusted on these stones without damaging the stone itself. Cleaning a slate stone takes only a few minutes; granite and especially marble markers take much longer. George’s marble marker, for example, took two people nearly two hours to clean. Once the stone passes the “toothbrush test” (so that a clean toothbrush will come up clean after it’s been rubbed on the stone), workers pack the stone back in the hole by using a fifty-fifty mix of sand and pea-stone to reset it at the proper height and angle. When it is stable and level, they replace the sod around it while recording the work that was just done. Simple enough, right?

While this seems like a reasonably straightforward process, every cemetery—and every stone—possesses its own character, shape, size, and, of course, challenges. Many stones are in perfect shape, but others have tortured angles or awkward bumps on them. Some have bricks, parts of other gravestones, or cement in their holes, revealing that this was not the first time they’ve been repaired. Stones that have broken into two or more sections are not uncommon, and these always require more attention and time. Broken slate markers can be reassembled with a quick-setting adhesive. Repairing broken marble and granite stones can be a bit more complicated. Preservationists usually drill holes into top and bottom sections and join the two together with a fiberglass pin. Sometimes preservationists will make an entirely new base for the stone out of wood forms and fast-drying concrete mix. However, preservationists must be certain not to set the stone itself into concrete, as that could catalyze further damage. Instead, an empty slot is left in the concrete form, and the stone is fitted in. The gaps are then packed with a strong but flexible and lime-rich mortar that gives the stone adequate room to shift while simultaneously keeping it sturdy and upright. In all cases, each stone presents its own personality.

What can preservation teach us about gravestones? The most obvious lesson is that gravestones are surprisingly frail. We assume that these markers for the dead are enduring and immovable. The truth is that they are, like the coffins and bodies below them, caught in a constant process of deterioration. Scholars, preservationists, and town and church administrators need to recognize that grave markers are not permanent and can’t be taken for granted; like any historic treasure, gravestones should be carefully protected and diligently preserved.

There are other lessons to draw from these stones. First, like any historical source, grave markers always unearth more questions than they answer. Although many stones record only a name, date of birth, and date of death, others give a fuller sense of the identities and relationships that contemporaries sought to memorialize. Women are often described in relation to men who either fathered them or married them, while the more eminent male lawyers, politicians, judges, and military leaders are remembered for their professional exploits. I have never seen a stone that reads shoemaker, midwife, tanner, or sailor; stones reiterate class and gender hierarchies. The funerary iconography of the stone can also reveal much about how the deceased’s families wanted to represent the wealth, character, or piety of the dead (figs. 3 and 4). Willows and urns eventually replaced the more grisly death’s heads in the late eighteenth century; cherubs seemed to operate as a transitional symbol between the two. Although markers might employ the same motif, the difference was in the details, and burial markers display a fairly wide range of detail and elegance. The more ornamental and meticulous images illuminate the stones of families that had the wealth and wherewithal to afford them. Indeed, participating in American funerary culture was in many ways a financial decision. The more elaborate designs are therefore found on the stones that recall the area’s most prosperous families.

Gravestone preservation also creates opportunities to introduce students to funerary rituals, ideas about death, and to provoke discussions about how past cultures imagined and experienced both death and life. Whether it is because my college students are fascinated with material culture, value gravestones as historical sources, or are simply obsessed with the macabre, they have been uncommonly interested in how the dead are memorialized. Taking students to a cemetery is surely the best way to bring early American death culture into the classroom. These visits allow students to see the stones firsthand, but also consider how they are laid out, along what kind of orientation they were placed, and how they fit in with the natural, institutional, or municipal landscape around them.

But because limits on time and money can make this sort of fieldwork difficult, if not impossible, I’ve had to look for alternatives. Indeed, if you cannot take students to the stones, bring the stones to students. Websites have been a tremendous pedagogical asset in this regard. There is an excellent Website on New York’s African Burial Ground that explains recent efforts to commemorate the site and broadcast its importance to the wider public. In addition, Keith and Theresa Stokes created a Website that documents Newport, Rhode Island’s famous “God’s Little Acre,” one of the oldest black burial grounds in North America. Including a historical overview of slavery in Newport, an explanation of African burial markers and names, and even photographs and transcriptions of dozens of black gravestones, the Website is an amazing yet underutilized resource for teaching about the African diaspora, material culture, and early American ideas about death (click here to watch a mini-documentary on God’s Little Acre).

Of course, the act of preserving a stone—whether physically through preservation or virtually by posting its inscription on the Web—highlights the myriad questions surrounding the actual meaning and purpose of the stone itself. This question is particularly salient in a classroom setting. Indeed, the irony of introducing students to gravestones and efforts to preserve them is that the actual meaning of the stone changes when doing so. No longer is the stone speaking solely for the memory of the deceased person below it, for it now serves as an entrée into a past world, one whose meanings and realities we constantly struggle to adequately understand. For example, when I was teaching an upper level course on the social and cultural history of early America, I distributed a packet that included a variety of documents on slavery and race in colonial Newport. The packet consisted of maps, laws, censuses, runaway and slave sale advertisements, manumission papers, diary extracts, and other primary sources. The goal was twofold. First, I wanted to teach my students about the dynamics of slavery in the colonial North. Secondly, I wanted them to wrestle with the nuances and complexities of different types of historical sources. Of course, I included images and transcripts of grave markers from God’s Little Acre. Interestingly, the grave markers ended up generating the most engaging discussion during this lesson, and one of the most intellectually exciting conversations we had the entire semester.

Duchess Quamino’s stone, for example, was an elaborately worded marker that said she was a “free black” (though she had previously been a slave) who was of “distinguished excellence, Intelligent, Industrious, Affectionate, Honest, and of Exemplary Piety.” The rest of the inscription reads, “Blessed thy slumbers in this house of clay, And bright thy rising to eternal day.” Some of my students took this marker to mean simply that Quamino was as the stone said she was: a pious, honest, and faithful Christian. This might have been true, but the words may hold further meaning. Before her emancipation, Quamino worked as a slave in the Channing household, and it was William Ellery Channing, the abolitionist and founder of Unitarianism, who added the poetic inscription to her marker. Quamino lived several years in a religious Anglo-American family, was married in one of Newport’s Congregational Churches, and had married a freed slave who became an ardent Christian; his death aboard a privateer’s ship during the American Revolution stopped him from undertaking an evangelical mission to Africa. So it is probably safe to conclude that Quamino likely personified a few of the traits inscribed on her stone.

But markers like Duchess Quamino’s also offer opportunities to discuss how gravestones served not only to honor the dead, but to express social conventions on race, religion, and power. Quamino might have been a pious, honest, and affectionate person, but framing her as such also spoke to the ways in which the Channing family wanted her to be remembered. Her marker certainly reflected well on her own personal qualities and achievements—”industrious” is an implicit reference to her success as a caterer and entrepreneur—but that’s not all. By depicting Quamino as a converted African who exemplified the best Christian qualities, the stone also highlighted the paternal care of the Channing family, which had presumably instructed her in the very principles that she personified so strikingly. While Quamino may or may not have been pious, someone certainly had an incentive for her to be described that way, especially a family of former slave owners who began to criticize the institution.

In other words, gravestones reflect the salient power relationships within any given society, especially one so clearly implicated in the social tensions of racial slavery. In fact, my students often debate whether slaves were considered products or people, and gravestones help to add nuance and complexity to this question. The stones that lie within God’s Little Acre can, in some ways, support the argument that slaves were perceived merely as commodities. Although all of the slaves buried in Newport were dubbed “servants” (and not slaves), most were described in some kind of relationship to those who legally owned them. Cato was a servant to Mr. Brinley, for example, and Captain John Brown was the master of his servant, Hercules Brown. Their identity was therefore inseparable from the masters who owned them, and even in death their status as slaves was engraved in stone. Coupled with newspaper advertisements that placed slaves alongside wool, rum, and other commodities, grave markers served to remind others that these people were in fact property. Even the location of the markers reifies these power relations, for blacks had their own separate burying place. In life they resided, worked, and lived with whites, but in death they were completely segregated.

And yet, many gravestones (and newspaper advertisements, for that matter) highlight the human qualities of black slaves; several were described as faithful, pious, exemplary. Even the fact that they were buried at all exposes their humanity, as does their apparent longing for a life after this mortal one, a uniquely human attribute. When juxtaposed against and used in conjunction with other primary sources, these gravestones reveal the fundamental social tension in Newport slavery: although these people were considered marketable commodities, their underlying humanity could never be totally denied,

Gravestones also reveal larger attitudes about the meaning of death itself, and recently preserved gravestones can aid in exploring these themes. In addition to the Newport assignment, my social and cultural history course also read Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering, which gracefully explores how the magnitude of death during the Civil War affected everything from how women in mourning sported the latest fashions to how entrepreneurs cashed in on the embalming craze. “Dying was an art,” Faust asserts, and for nineteenth-century Americans, a “good death” meant lying at home surrounded by family, rejecting Satan’s temptations, and dying peacefully, penitently, serenely. However, and as Faust makes clear, the unprecedented exigencies of the Civil War ensured that soldiers were unlikely to experience a “good death.” Sniper fire, ruthlessly effective weaponry, astronomically long casualty lists, exploding bodies, and mortal anonymity rent a hole in this practice while fundamentally challenging Americans’ notions of what dying actually meant.

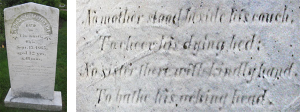

The recently preserved gravestone that began this article encapsulates this idea tidily. According to his marker, George L. McIntire died just shy of his thirty-third birthday in September 1865 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Was he a victim of the war? It is tough to say, but whether he died in the war or not, his morose inscription clearly reveals that the distance between him and his family prohibited a “good death.” It reads:

No mother stood beside his couch,

To cheer his dying bed;

No sister there with kindly hand,

To bathe his aching head

If McIntire was a casualty of this war (or some disease that resulted from it) the stone does not mention it (figs. 5 and 6). Instead, McIntire’s marker offers a critical narrative of a bad death, one where the victim’s body was in social isolation while his soul was in spiritual peril. The stone therefore functions not as a celebration of this individual’s life, but rather as a commentary on the perils of westward migration and family disruption. Although his may not have been a Civil War death, the stone’s message appropriates the same conventions about the “good death” to portray McIntire’s death as a bad one, or at least one comparable to those that hundreds of thousands of men experienced during the recent war. This man died fairly young, away from home, and alone, and the inscription on his marker implicitly warns other members of the family and the younger residents of Wellesley to avoid the same fate. In the end, the stone is not really about McIntire, but about the anxieties and fears that migration might cause for all members of a family. In drawing such attention to this bad death, McIntire’s stone functioned as a cautionary tale, a brusque reminder of how others might experience a “good death” while avoiding a regrettable one.

Cemeteries and the gravestones that reside within them unearth a panoply of human emotions: sadness, regret, and loneliness, as well as happiness, nostalgia, and beauty. Indeed, if there is no place more haunting than a cemetery at night, there are also few places more idyllic in the day. When we cease to think of cemeteries simply as places to deposit our dead and more as open-air museums, their intrinsic value becomes even more apparent. As living museums, cemeteries require no admission fees and have no curators. Indeed, gravestones may be silent reminders of the lives of the past, but if meticulously preserved and carefully interpreted, these stones can speak to us. But rather than speaking in one narrative chorus, grave markers reveal a host of meanings, conventions, and voices. Preservationists are working diligently to keep these voices alive, and we would be fortunate if future generations did the same for ours.

Further reading:

The historical literature on death and funerary rituals is too broad to comprehensively summarize here. The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife has published several volumes on Puritan gravestone art. For more on how death in the Civil War affected its meaning, practice, and understanding in American society, read Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York, 2008). For a diverse collection of scholarly essays on death in early America, take a look at Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein, eds., Mortal Remains: Death in Early America (Philadelphia, 2003). Michael G. Kammen’s new book, Digging Up The Dead: A History of Notable American Reburials (Chicago, 2010), examines why some people decided that one burial for extraordinary Americans was simply not enough. Finally, and for an intercultural approach to death in the first few centuries of American encounters, read Erik R. Seeman’s Death in the New World: Cross-Cultural Encounters, 1492-1800 (Philadelphia, 2010).

For more on the historical archaeology of Newport’s “God’s Little Acre,” see James C. Garman, “Viewing the Color Line Through the Material Culture of Death,”Historical Archaeology 28:3 (1994): 74-93. In addition to the Website dedicated to “God’s Little Acre,” Keith and Theresa Stokes also created an award-winning site on African American and Jewish history in Newport. It can be found at www.eyesofglory.com.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.2 (January, 2011).

Edward E. Andrews is a visiting assistant professor at Providence College in Rhode Island, as well as a part-time grave preservationist.