Do Not Despair: Suicide in the archives

When I tell people that I am thinking about suicide, most tell me I should not let graduate school get me so down. In truth graduate school has me anything but down; my dissertation project—a study of the significance of suicide in the newly United States—gets me up in the morning and keeps me up late into the night. While my advisors have been careful to make sure I am not getting too involved with my subject, the topic has proved so fascinating that I have rarely had time to ponder the darker side of dissertating. And I am not the only one fascinated by suicide. When people learn that I study suicide, the questions always follow thick and fast: How many early Americans killed themselves? Why did they do it? How?

Back when I started this project, those were the same questions that drove me; reconstructing an early American suicide rate from coroner reports seemed like the foundation of any substantive analysis of this topic and I refused to be deterred by the conspicuous absence of previous quantitative work. I soon learned my lesson. With the laws of most states stacked against self-murder (through the 1810s suicides in Massachusetts were punished with a stake through the heart and a roadside burial), not to mention considerable social and religious stigma, there was every reason to cover up a suicide. When Mary Ware, the wife of Harvard President Henry Ware, took her life in 1807, her intentionality was largely withheld from the public record, meriting only an ambiguous mark next to her name in a church ledger. And she was not the only one. Victims, their families, and coroners often conspired to make difficult deaths disappear. If it was accuracy I was after, I quickly discovered that coroner reports were not going to get me very far. So I instead began to look for a discrete community with a multifaceted source base. I found one sitting on the shelves of my university library. Notoriously thorough, the eighteen volumes of Sibley’s Harvard Graduates reconstruct the lives and deaths of each graduate of the college from decades-long researches into every archival corner. Even if the coroners did not pick up on a suicide, Sibley, I thought, probably would. Excited, I added in information drawn from similar biographical projects at Yale and Princeton to produce a large data set. It turns out that twenty-nine of the seven thousand college graduates whose exploits are recorded in these exhaustive minibiographies definitively committed suicide. The number of possible and likely suicides runs much higher. But as I crunched the numbers, bringing all of my high-school math to bear on the problem, I soon realized that the sample is far too small to say anything beyond the tantalizingly suggestive about the suicide rate of this population. Real scientists would throw out the data.

Despite this setback, the exercise was not a complete failure. Reading in Sibley’s teeming volumes, I became overwhelmed by the range of sources, going far beyond coroner reports, in which he and his team had found references to suicide. Early American diaries, I have discovered, are full of them. Sibley led me to John Pierce, a long-serving minister from Brookline and author of a twenty-volume journal. Pierce, who graduated Harvard in 1793, spent the next fifty years recording the deaths of his classmates and parishioners, taking unique pleasure in his own longevity. Suicides drew his particular attention. In 1833 he sat down to record details of all the local suicides that came to mind, offering his own speculations as to their motives and even transcribing a suicide note that had come into his possession. Its author, David Ackers, used his final communication to blame a combination of bad luck and lotteries for sending him “fast down the broad road to destruction.”

The diaries of other early Americans evidence the same interest in suicide. There are, if you are keeping score, twelve suicides in Martha Ballard’s diary, and more than forty in William Bentley’s. Elizabeth Drinker goes so far as to critique the choice of exit of an unnamed slave who jumped to a noxious death in his master’s privy. “The river was running within a few yards of the house,” Drinker pointed out. “[W]hy did he not prefere that more cleanly, and I should think, more easy method?” The diary of Eliza Cope Harrison offers even more. In addition to his considerable curiosity about the suicides of his fellow city-dwellers, Harrison’s diary provides a rare portrait of a man considering taking his own life. In an entry written after midnight on March 10, 1803, Harrison, a failing Philadelphia businessman, confided that he had decided to “rush into the presence of my God, uncalled.” Yet the sight of his daughter, asleep in the room, soon got the better of him. “I pause,” he wrote, “shall I do this thing?” Tears followed and the awful moment finally passed. Calming himself, drying his eyes, he eventually rose, closing his entry: “I will embrace the auspicious moment, carry my lovely infant to her mother & seek to compose & drown my cares in sleep.”

While a treasure like Harrison’s expansive diary is still best discovered in the original, spending wet New England Wednesdays trawling through unindexed diaries and letters has often left me frustrated. Thankfully, those of us engaged in needle-in-haystack projects can now supplement our researches with a wide variety of indexes and databases. Ballard’s diary, the centerpiece of dohistory.org, is now digitized and enabled for full-text searches. The Library of Congress’s public-access American Memory project has also helped me comb large portions of the papers of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington for references to suicide that might have taken months to find otherwise. The North American Women Letters and Diaries initiative, a subscription service, allows similar searches among the personal documents of more than a thousand women from the colonial period through 1950. How else would I have discovered that in 1836 Lydia Sigourney had attended a lecture at which the tight lacing of bodices was compared to suicide?

The same fascination with suicide that led so many Americans to detail and debate the subject in their diaries led others to preserve artifacts from the event. Researching a paper about suicide notes in the media, I found to my surprise that the Massachusetts Historical Society not only had a few, but had even indexed them in the card catalog! When I began examining newspapers for evidence of and reaction to self-murder, I found even more suicide notes, transcribed and scrutinized to a degree that seems intrusive even by modern standards of journalism. Indeed, for a subject as sensitive as suicide, the pervasiveness with which it infused the media of the early republic is amazing, especially considering the extent to which newspaper editors were complicit in covering up awkward exits. Of course, everyone knew what was going on—cover-ups were so common as to become subjects in themselves. As the self-styled preacher, poet, and peddler Jonathan Plummer wrote in a broadside in 1807, “The relations of those who dispatch themselves are often desirous of keeping the thing as private as they conveniently can, and printers out of pity to them, or from some other motive, are often induced to withhold in public papers a part of the truth in regard to such matters, mentioning the deaths of the deceased in such a way as to lead a reader to expect that they departed in a natural manner.”

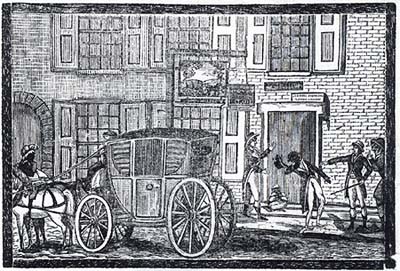

![Fig. 2. Having been separated from her husband, this slave woman unsuccessfully attempted suicide to avoid transportation to Georgia. A caption reads, "[B]ut I did not want to go, and I jump’d out of the window." Detail from Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, in the United States . . . (Philadelphia, 1817). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/4.4.Bell_.2-240x300.jpg)

So it is remarkable, then, that suicide appears with such regularity in the newspapers of the early republic. While underreporting was considerable, newspapers, it seems, took a distinct interest in particular types of suicide. Suicides that occurred in public places, for instance, were hard to ignore, and the suicides of those whose families lacked the social and political capital to engineer a cover-up were often splashed across the inside pages. Deaths that were particularly elaborate, instructive, gruesome, or exotic, or those that furnished a suicide note, also appeared with considerable frequency in the prints.

Despite their ubiquity, finding suicide stories, however sensational, amongst the mass of newsprint that washed over the early republic feels like a test of endurance. So in addition to systematic searches of the microfilmed newspaper collections of my university library, I have recently been exploring new electronic newspaper indexes. The CD-ROM index of Niles’ Register, and the free Web-based index of the American Periodical Series have both made looking for needles in haystacks a much less daunting prospect. Likewise, the full-text searching possible in the online Pennsylvania Gazette, a subscription service, has saved hours hunched over decrepit microfilm readers, while the Performing Arts in Colonial America CD-ROM has brought together a diverse collection of newspapers and periodicals for subject-level searching. At the American Antiquarian Society this winter, I road-tested a demo for the Readex Early American Newspapers Digital Edition, a new full-text database that I hope will do for newspaper research what their Evans Digital Edition (previously discussed in this column) has done for research in American printed books and ephemera. As with Evans Digital, the real barrier to researchers will be the prohibitive cost of subscribing to this new and powerful tool: when Harvard University balks at the subscription fee, as it has for Evans Digital, you know there is a steep price to be paid.

As these new databases and indexes are confirming, suicide was a staple of early American newsprint, but early Americans’ infatuation with suicide does not end there. Discussion of suicide infused almost every medium in the early nation. Pamphlets, plays, poetry, and periodicals overflowed with news and opinion about bloody tragedies, both real and imagined. Americans puzzled over gory familicides, sensational slave suicides, and the suicides of convicted criminals in the nation’s prisons and jails. Indeed, lured by the gripping illustrations of slave suicides found in various antislavery publications, I have recently moved suicide and slavery to the center of my dissertation project.

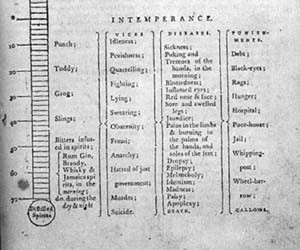

In texts where actual suicides were absent, the language of self-destruction and self-preservation was brought to bear on all kinds of social behaviors deemed threatening to the health of the republic. As Lydia Sigourney discovered at Dr. Mussey’s lecture in 1836, early American reformers compared just about anything to suicide in order to forward their arguments. Dueling was suicide; gambling was too. Habitual drinking was a choice that could only end in death. Benjamin Rush even designed a “Moral Thermometer” to show exactly which spirits would put you on path to self-destruction. (If you are concerned, steer clear of whisky, gin, and brandy).

Working through Rush’s temperance papers this past summer, I discovered that the good doctor was not all talk; he also actively worked to prevent suicide. Coming across his membership certificate to an unfamiliar reform society, I stumbled upon the Humane Society of Philadelphia, an antidrowning group for which Rush served as vice president. Usually centered around local physicians, these societies attempted to curb the seemingly ever-increasing number of deaths in the nation’s rivers, lakes, and harbors by the strategic placement of medical equipment and instructions on bridges and ferries where drownings often occurred: “Do Not Despair,” one prominently placed riverside sign told those who lingered in its vicinity. Armed with lifeboats and with new ideas about suspended animation and resuscitation, members of these humane societies established what might be properly understood as the first American suicide prevention centers.

My recent interest in prevention and moral reform is symptomatic, I think, of the change in direction my research has taken since I first opened a volume of Sibley’s Harvard Graduates and set about trying to compute a suicide rate. “Who?” “how?” and “why?” now seem less important than “so what?” I may have despaired about ever knowing how many early Americans committed suicide, but my journey through diaries, newspapers, pamphlets, and letters has shown me that that is not really what matters. How Americans in the early republic responded to suicide or the threat of it and what they understood that threat to be are now the questions that keep me up at night. I still do not have any good answers, but I will not despair just yet.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.4 (July, 2004).

Richard J. Bell is a graduate student in the history department at Harvard University. He is embarked upon a dissertation entitled “The Cultural Significance of Suicide, 1760-1830.”