Eighteenth-Century Letter-Writing and Native American Community

Having recently spent some time at my parents’ house helping them downsize, my sister and I came upon several shoeboxes crammed with letters—from my parents to their parents, from my sister and I to our parents, and from various friends and relatives to all of us at different moments in our lives. Some of those letters mark momentous events in the history of my family. Most, however, are quite mundane, marking the ordinary passage of time before e-mail and phone calls once and for all replaced our exchange of letters. The pleasure of revisiting dear and familiar handwriting, some of which I hadn’t seen in decades, came back in a flash, evoking vivid memories of people once central to my life.

Mine is probably the last generation in this country to have a felt experience of epistolary exchange now that electronic media have largely replaced handwritten exchanges as the communication mode of choice. Of course my experience of epistolarity is hardly the same as the eighteenth- and nineteenth- century Native American subjects of my book, English Letters and Indian Literacies, for whom the only tie to family—sometimes for years at a stretch—was the letters that passed between them. Nonetheless, letter writing involves a set of shared practices and conventions that are gradually passing away at this moment. It is perhaps for this reason that scholars have turned their attention with such enthusiasm and insight to the familiar letter of the past. Through careful analysis of letter collections in British and American archives, scholars remind us that eighteenth-century correspondents were part of a rising generation for whom letters were an increasingly essential part of their lives. Rather suddenly, through vastly expanded literacy as well as increased access to the material conditions necessary for letter writing, better and more efficient transportation of letters, and the dispersal of families that characterized so much of the colonial American experience, ordinary people put pen to paper and marked out their everyday lives and experiences. Increasingly in the eighteenth century, letters became a central means of communication and connection not only for elite families, but also for a variety of people in all walks of life. In New England this included Native American communities living on the outskirts of English settlements.

Epistolarity as Social Network

For all the ways that letters and the conventions of epistolarity are familiar to those of us of a certain generation, recent scholarship reminds us of the many ways in which eighteenth-century letters were produced and consumed very differently—certainly in the Native communities of New England. The implied dyad of the letter writer and recipient that we take for granted today is more or less a fiction: the letter writer may not have been a single individual since a letter might include messages to and from others, especially family members. For those whose literacy was not firmly established, the letter writer might more properly be considered its composer, with a scribe (either paid or acting out of kindness) writing down the actual words. Then, of course, there was the matter of delivery, which might include formal postage, but just as likely might involve a friend or two, or even a passing stranger willing to carry letters; letter delivery, especially for transatlantic mail, was dependent on transport routes, shipping patterns, and trade vessels. Finally, the recipient of the letter would be not only the person to whom the letter is addressed, but would generally include a variably sized group of people—other family members, community members, and even passing visitors and friends with whom one might share all or part of the familiar letter, which would most often be read aloud upon its receipt—sometimes even by the person who had delivered it, who might be expected to carry a return message. There was rarely any expectation of privacy in epistolary exchange, and letters served to consolidate relations that at times crossed from personal to political or financial exchange.

The materiality of letters was of course strikingly different as well, as scholars from Konstantin Dierks to E. Jennifer Monaghan remind us, and access to the technologies of literacy (the right quill for a pen, proper ink, a flat surface for writing, light, paper, and, of course, the leisure to compose a letter) was a challenge for many of the Native correspondents of New England. There was always the fear of letters getting lost, stolen, misunderstood, or misplaced—especially with the formal mechanism of the postal system involved, as Eve Bannet and Lindsay O’Neill have both suggested.

Even so, the class barriers to epistolarity that scholars have tended to assume were there have been challenged in several important recent publications, and evidence of what scholar Susan Whyman calls “epistolary literacy” has been recovered from a range of transatlantic archives: letters among servants and between members of nearly impoverished families form part of the expanding world of the familiar letter. Whyman argues that the expansion of letter writing had a democratizing effect, and that the array of letters among the “lower and middling sort” suggests a far greater network of informal literacy training than had been previously understood. As the clearer and easier form of cursive known as the “round hand” replaced the far more complex and formal handwriting of earlier generations, writing became more accessible in the eighteenth century, as did the proliferation of copybooks through which novice writers developed and perfected their skills. Whyman’s work reinforces what I and others have found in New England archives: the papers of writers who nobody thought could write. Embedded within those letters are references to far more letters than those that remain.

These new discoveries have transformed the way modern scholars approach Native history. Where once the assumption that Native Americans operated outside literacy systems was so powerful that all evidence of Native self-expression was overlooked in favor of English colonial assessments, it is now a core practice of contemporary scholars to first seek the words and expressions of Native people. Letters are one form among many through which Native experience is marked and recorded, but they are an extraordinarily telling one. Thanks to two recent digital collections, the Occom Circle and the Yale Indian Papers Project (now Native Northeast Portal), scholars of early New England Native studies today have access to documents by and about Native Americans in a way that was once unimaginable. Through these two digital sites, both of which are freely available to anyone with a computer and access to the Internet, original documents, including letters, are available to all of us (or will soon be) in very tangible ways—a vast improvement from the microfilm versions that once were the godsend of scholars like me who live so far from their sources. These digital archives are extraordinary. Even for those with only the most fragmentary knowledge of the history and culture of eighteenth-century New England, these collections offer a most tantalizing glimpse of the lives of Native Americans. Each includes a high-quality digital image of the original document, a transcription of the documents, and useful annotations that help situate these works and the people involved.

Much like the shoeboxes of letters in my parents’ house, archival collections result from strange combinations of the momentous and the mundane. Sometimes papers remain simply because nobody threw them out; others remain because they matter deeply as evidence of some element of family or community pride or identity. More often collections—especially letters collections—are a combination of the two, and as outsiders we can never really know with certainty which are the momentous documents and which are not. Rather than establishing which is which, the Yale Indian Papers Project (now Native Northeast Portal) is an ambitious attempt to provide a more comprehensive digital repository for papers from multiple archives (Yale University, the British Library, the Connecticut State Library, the Connecticut Historical Society, the Massachusetts Archives, the National Archives of the United Kingdom, and the New London County Historical Society) documenting some element of Native New England for the last 400 years. Along with letters, the YIPP includes such odd snippets as runaway ads for Native American servants, with their detailed descriptions of eighteenth-century clothing. Also included in that archive are petitions, legislative reports, and summonses. These are the ragged edges of peoples’ lives, often made visible in the archive at their most difficult or fragile moments, when they have in one way or another engaged with a civil body either through the courts or through a legislative petition. At the same time the YIPP offers letters and whatever else may shed light on the vast and complicated network of Native experience in New England, from celebrations of community to acknowledgements of loss and hardship. The accidental intimacy of the letters in this collection as opposed to other kinds of documents provides a hint not of the ragged edge, but of the everyday.

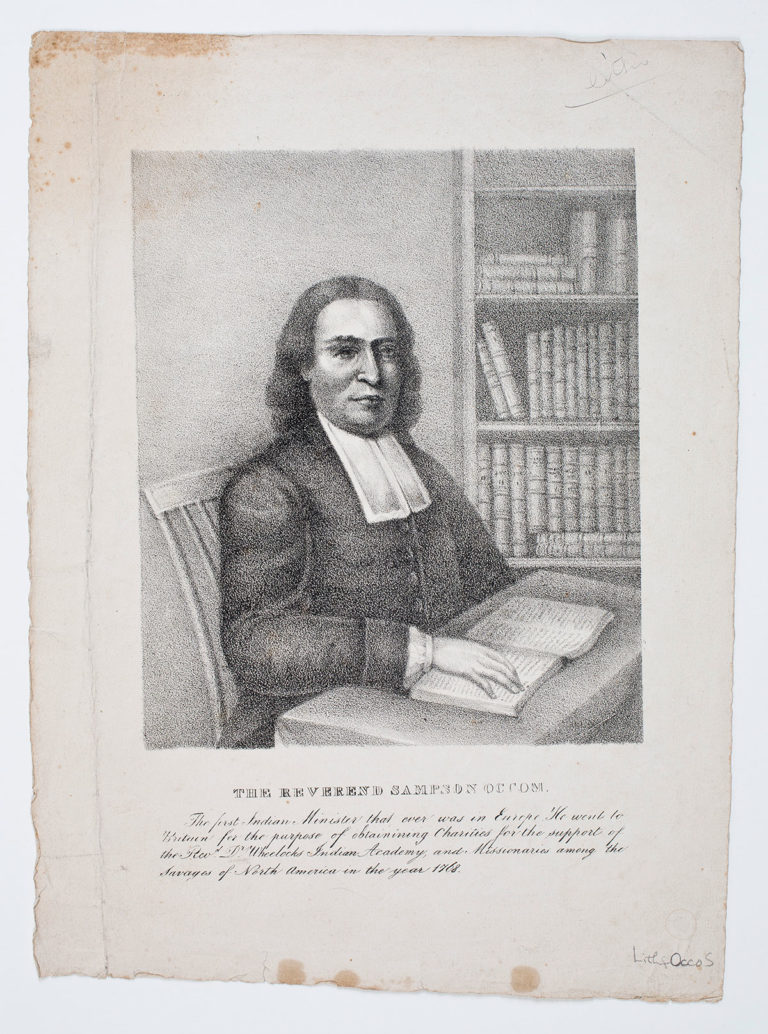

The letters known as the Occom Papers at the Connecticut Historical Society that are now (or will be very soon) available through the Yale Indian Papers Project provide a glimpse into the experience of one Native family network. This particular archive is extraordinary because although it was donated to the Historical Society by Norwich resident and U.S. Representative John A. Rockwell in 1839, the archive itself seems to be the result of the choices (accidental or not) by the Mohegan minister and political leader Samson Occom and generations of his family about what to keep. Together with the letters and documents in the Occom Circle, which contains even more letters, confessions, account books, lists, diaries, reports, and sermons by and about Occom, these papers may well provide one of the most comprehensive records of this Native American family. The Occom Circle focuses primarily on the Native students and teachers connected to Moor’s Charity School, which was founded by Eleazar Wheelock in 1754. Samson Occom was central to the establishment of this school, which educated more than sixty-five Native students before moving to New Hampshire and becoming part of Dartmouth College. The Occom Circle rightly restores Occom to his central role in what eventually became Dartmouth College, and the archive offers us a window into the lives of the Native students, the English and Colonial benefactors of this school, and a variety of records in some way connected to Occom, including records concerning the founding of what eventually became the Brothertown community.

In the context of this extensive family history, a short letter by Olive Adams, written in 1777 from Farmington, Connecticut, stands out. Olive, a twenty-two-year-old Mohegan woman at the time she wrote this letter, never attended Wheelock’s charity school featured in the Occom Circle, and in fact her educational background is unclear. She writes:

“Hon.’d Father and mother I tak this opportunity to inform you that we are well but not so strong ^as I have been we have never heard from any of you Sence Hon.’d Father was hear but I hope these few Lines will Find you all well as they Left us I hope mother will not Begroudge the time to vesit her unfortunat Daughter, Please to Bring Brother Andrew Giffard, th Docter if you can For we long to see him hear. Pleas to send us letters every opportunity you have and we will do the same. Nomore From your Dutiful Daughter Olive Adams.”

To which she adds the following postscript: “Pray mother to bring my cotton yarn, and bit Red broadcloth to pach my old cloak. Remenber our love to our Brothers and Sister and to all their that inquir after us if thers any such.”

In many ways, of course, this is an insignificant letter: poorly written, phonetically spelled, it contains little other than the most benign family news: everyone is more or less well, and it would be great to receive a visit, or at least some letters.

And yet. The year is 1777, and the American Revolution is raging. Young Olive, originally from Mohegan, has been married for about two years to Solomon Adams. Adams was a Tunxis Indian living in Farmington and an advocate, like Olive’s father, of an emigration movement through which the Native Christians of a variety of Algonquian communities throughout southern New England planned to band together to form a single community on upstate New York called Brothertown. Plans for this new community had been suspended because of the war, and so for now everyone waited. Most significantly, the parents to whom Olive writes are Samson and Mary Occom, the honored parents of ten children (the youngest of whom, the Andrew Gifford mentioned in this letter, is just a toddler) and the spiritual leaders of a Christian Indian diaspora throughout New England. The intertribal family connections are dizzying: Samson Occom and his brothers-in-law, Montauketts Jacob and David Fowler as well as his sons-in-law, Solomon Adams (Tunxis) and Joseph Johnson (Mohegan) are all deeply involved in this new community, and beyond their interconnections as an extended community of Algonquian New Englanders, these men all shared a strong commitment to literacy and Christianity as means of maintaining Native community.

Both Samson Occom and his son-in-law Joseph Johnson were prolific writers who had acquired their educations from Wheelock’s school, and they were both widely recognized throughout New England for their erudition. Indeed, the words of fathers, brothers, nephews, and sons are all there in the historical archive with their formal address and rhetorical flourishes. What Olive’s letter tells us, however, is a slightly different story. Hers is the story of mothers and daughters and sisters and wives, and the ways in which women participated in networks of community specifically as literate figures.

Reading carefully, we can also discern some clues about the education that Olive would have received as a young girl. When travelling in Great Britain in the latter part of the 1760s, roughly a decade before Olive’s letter, Samson Occom wrote to his wife, “try to instruct your girls as well as you can.” In another letter, he wished her to “instruct our children in the fear of God as well as you can, and send them to school as much as you [blank] advisable if the school continues.” But while his son Aaron briefly attended Wheelock’s school, none of the Occom daughters ever did. Most probably the Occom children were occasional students at the one-room schoolhouse at Mohegan. They cobbled their education together from their mother’s instruction, their father’s teaching (when he was home) and whatever schooling was available at any given moment. They were certainly surrounded by educators: both their uncles and their father served as schoolmasters, and several of the Occom daughters married schoolteachers as well.

Native Families Creating Networks of Literacy

Indeed, Olive Adams’ laconic letter tells us a vivid story of the networks of literacy through which Native families cemented their connections across time and distance. From yarn and cloth to family visits and sibling relationships, Olive’s letter marks the ways in which family-based literate practice did as much to maintain Indian community as any political or legal document. The local school may have been an uneven presence, but the existence of Olive’s letter suggests that her family probably did more to produce her literacy than any educational establishment ever could.

However she acquired her skills, Olive’s letter points not only to her ability to form words and letters, but also to her familiarity with the conventions of epistolary address that shaped letter-writing in this period. Olive’s letter is generally laid out appropriately, with the properly situated date and location in the upper right-hand corner, the salutation on the left margin, and the formal language of respect directed to her parents, especially her father. While Olive could on occasion expect visits from her itinerant minister father, she was much less likely to see her mother and siblings, so letters allowed her to maintain her connections to her large family. In this difficult moment of community dispersal and fragmentation, letter-writing was as essential to maintaining connections and strengthening community as the complex political negotiations among Native communities and with colonial political bodies that would culminate in the Brothertown settlement. Letters stood in for individuals, and exchanges of material items—yarn, cloth—sometimes had to stand in for personal affection.

The very ordinariness of this letter confirms that literacy was far more widespread than we perhaps understood. The mundanity of Olive’s letter almost guaranteed its disappearance: such letters rarely survive more than a few weeks—never mind centuries. For whatever reason, however, her father kept this letter, and so we have it. And while it is exceptional within the archive, it is likely that this was not an exceptional letter at all, but rather one of many that exchanged hands in the volatile years of what Colin Calloway has termed the American Revolution in Indian country. Olive asks for family visits, certainly—but she also asks for letters. The request for letters is a refrain that runs throughout the correspondence Occom received from his Native friends and family throughout the 1770s and ’80s. Even the most tenuously connected people wrote to him asking for letters, or for news from home, or for permission to pass along letters for their own family through him. Literacy, in other words, connected certain Native families and communities in colonial America, serving not only a political function, but a personal and social one as well.

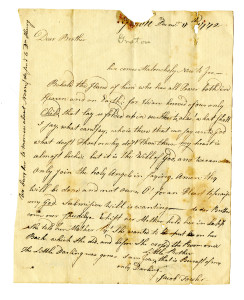

A very different kind of letter is also gathered into the Occom Papers archive, one written five years earlier by Jacob Fowler, Samson Occom’s brother-in-law and Olive Adams’ uncle, living in Groton, Connecticut. If Olive’s letter is remarkable for its every-day serenity, Fowler’s letter stands out for its raw broken despair. In it, Fowler records the devastating loss of his only child and the spiritual crisis that this entailed for him. He writes on a single sheet of paper:

Dear Brother

Here comes Melancholy News to You—Behold the Hand of him who has all Power both in Heaven and on Earth, for we are bereved of our only Child, that lay so folded up in our Hearts, alas! what shall I say what can I say; who is there that can say unto God what doest Thou or why do’st Thou thus. – my heart is almost broke: – but it is the Will of God, and we can only Join the holy Angels in saying, Amen : thy Will be done and not ours. O! for an Heart to praise my God. Submissive Will is wanting – do der Brother come over Speedily. Whist her Mother held her in Lapp She told her Mother tht She wanted to put on her Back. which She did and before She cross’d the Room once the little Darling was gone = I am Your Little B[r]other that is Bereaft of my only Darling –

Jacob Fowler

Sideways on the same sheet: “We bury her to morrow about Noon do send to Dr Henry.” If this letter had not been preserved, Jacob Fowler would exist in the archive as a flattened, abstracted figure notable for his connections to others rather than any signal act of his own. His older brother, David Fowler, had an important role in Wheelock’s school and the narratives that advertised it; his brother-in-law Samson Occom was essential to bringing his much younger brothers-in-law to Wheelock’s school in the 1760s and remained a central figure in their lives throughout their adult years. For much of his life, Jacob Fowler was there with his family, supporting the Brothertown initiative, working as an itinerant minister and schoolteacher, rarely stepping out of the archive in any way that separated him from his active, powerful family.

Here, however, is a wail that crosses the centuries, a crisis of the heart that instantly humanizes him. The letter itself touchingly breaks down; it starts in clear and graceful handwriting and then gets increasingly fragmented. After the words “Submissive Will is wanting” there seems to be a break: the handwriting shifts, the spelling is erratic, the ink is blotted, words are crossed out, and the words “Little B[r]other” are inserted above the final sentence, which otherwise makes no sense. The emotion attached to the brief description of his darling daughter’s final moments is vividly marked on the page, and Jacob Fowler, father, husband, schoolmaster is reduced to a “Little Bother”—clearly a slip of the pen that elides the “r” in “Brother” with the lower loop of the “B” but a telling one nonetheless—he is extraneous in the world, useless without his “little Darling” who once lay “so folded up in our Hearts.”

Indeed the tension between the words of the good Christian: “it is the Will of God, and we can only Join the holy Angels in saying, Amen: thy Will be done and not ours” is in striking contrast to the outbursts in which Fowler challenges that God: “O! for an Heart to praise my God. Submissive Will is wanting.” Lost in his despair and grief, he begs his brother to save him from his own doubts. Fowler can barely admit his own crisis: his acknowledgment that he resists God’s plan is written in the passive voice (“Submissive Will is wanting”) and the broken-hearted (and broken-phrased) description of the last moments of his child’s life hint at the regret and despair that he feels: why did his wife put her down? Why were they not holding her at the end? Why couldn’t this beloved child have stayed with them longer? While the letter opens with the shared loss that he and his wife have experienced (“we are bereved of our only Child, that lay so folded up in our Hearts”), in the end he is isolated in his own grief, despairing the loss of his “only Darling.” “Come over Speedily” he begs Occom, underlining the word “speedily” for emphasis. Did Occom keep this letter because he was there for Fowler in this moment of need, or was he haunted by his inability to comfort his grieving brother-in-law? Did the letter get there in time, or did Occom receive it after the crisis had passed? Archives ultimately reveal only so much.

As I do for the letters in my family’s house, I have a visceral sense of familiarity upon seeing the particular handwriting of these eighteenth-century correspondents, so familiar and yet so distant. I know them, I sometimes tell myself; we share a set of memories and experiences. Their letters aren’t addressed to me, and yet somehow they have come into my hands (always carefully and in accord with the rules of the archive, of course), and so I have an obligation and a responsibility to the stories that they tell. Yes, both a familiarity and, if I’m honest, an affection for that dear and familiar handwriting, so much a part of who these people are and were. I know them by the particular arch of their Ds, the flourish of their signatures, or even the distinctive shapes of their vowels and consonants, their commas and their periods.

Of course, these are simply the stories I tell myself. These letters were never written with me—or anyone like me—in mind. The sense of intimacy that draws me to Olive Adams and Jacob Fowler is entirely of my own making. Considering that I don’t know much of anything about them—what they looked like, how many children they had, what they thought about in the long stretches between the handful of letters that remain—my sense of intimacy with the writers of these letters is, of course, entirely one-sided.

And yet it has been an honor and a pleasure to get to know these correspondents; accidentally or not, I have been privileged to get a peek at their lives and their experiences. I certainly do not pretend to fully understand the lives of these young Native American writers, but their letters have marked me, and I hope I have served them well in reminding us of the work that went into the production and dissemination of their words and letters.

Further Reading:

On eighteenth-century Native New England: Joanna Brooks, The Collected Writings of Samson Occom, Mohegan (2006); Linford Fisher, The Indian Great Awakening (2012); Laura Murray, To Do Good to My Indian Brethren (1998); Hilary Wyss, English Letters and Indian Literacies (2012)

On letters and letter writing more generally: Eve Bannet, Empire of Letters (2005); Konstantin Dierks, In My Power (2009); E. Jennifer Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America (2005); Lindsay O’Neill, The Opened Letter (2015); Sarah Pearsall, Atlantic Families (2008); Susan Whyman, The Pen and the People (2009).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.2 (Winter, 2016).

Hilary E. Wyss, Hargis Professor of American Literature at Auburn University, has written extensively on Native literacy and community in early America. Her most recent book is English Letters and Indian Literacies: Reading, Writing, and New England Missionary Schools, 1750-1830.