Eyewitnessing and Slavery

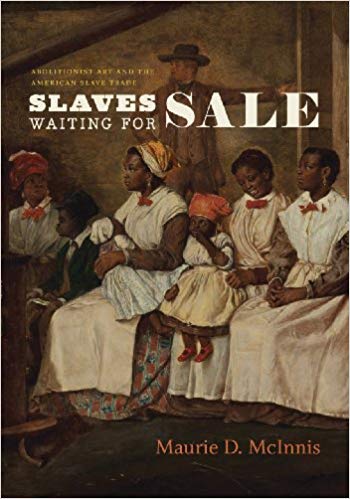

On March 3, 1853, little-known British artist Eyre Crowe entered an auction room in Richmond and saw nine slaves sitting on benches, waiting to be sold. Crowe took out his pencil and paper and began to sketch. Eight years later, he turned this sketch into a painting. As the Civil War began, viewers at the ninety-third annual exhibition of the Royal Academy of the Arts in London first gazed upon Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia (1861).

Crowe’s painting pictured nine of the more than two million slaves sold in the domestic slave trade in antebellum America. Over the past three decades, historians have made this vast network of human commodification central to any understanding of antebellum bondage. They have produced numerous studies that illuminate the quantitative dimensions of the trade and explore the meanings of individual sales for masters and bondspeople. Visual culture scholars have separately explored visions of slavery, paying particular attention to depictions of the southern plantation and the moment of emancipation. But the question of how artists visualized the domestic slave trade has awaited a fuller answer.

Art historian Maurie D. McInnis takes up this question in her richly textured book Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade. Examining how Eyre Crowe made the domestic slave trade visible, McInnis makes an important contribution to the visual history of antebellum slavery. Crowe’s simple act of eyewitness artistry, McInnis compellingly argues, produced an “exceptional” and “unique” painting of American bondage (10). It largely eschewed the conventional uses of stock characters and stereotypes for African Americans and the characteristic emphasis on the theatrical drama of the slave market. In the spring of 1861, Crowe’s painting invited viewers in London to ponder the perspectives of individual slaves, rather than the overall action of the auction.

McInnis structures her book as an archeology of this 1861 painting. In the first six chapters, the heart of the book, McInnis assesses Crowe’s work within a longer history of slave trade imagery, connects Crowe’s artistry to his actual journey in 1850s America, and contextualizes this story of image-making within the broader social contexts of the slave trade. In the seventh and last chapter, McInnis moves from America to London to explore the display of Crowe’s image.

Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia broke in significant ways from past antislavery visions of the trade, McInnis asserts. In the late eighteenth century, British abolitionists began targeting the slave trade by widely circulating the Plan and Sections of a Slave Ship. McInnis suggests how this vision of bodies packed into a Middle Passage vessel pictured slaves as anonymous commodities rather than Crowe’s individual subjects. In the antebellum era, well after the fall of the international slave trade, American abolitionists consistently turned to the domestic auction block for propaganda. In publications such as the American Anti-Slavery Almanac, abolitionists decried the tragic separation of enslaved families. Images cast the sale as spectacle, such as an illustration in George Bourne’s Picture of Slavery in the United States of America: a raised stage; an auctioneer commanding attention with his arm in the air; a group of whites hovering and measuring a slave’s body. McInnis notes how Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia also suggested that family separations had likely happened, picturing a lone man in the corner, and that they might happen again, showing women with their children. She briefly notes the distortions of the young boy’s facial features. But McInnis stresses how Crowe refrained from racial caricature in depicting most other subjects. She emphasizes the ambiguous facial expressions of many of the women, and the unusually defiant look of the crossed-armed man. For McInnis, Crowe’s painting extends certain themes of past slave trade depictions, but distances itself by largely picturing individuality and uncertainty rather than anonymity and theatricality.

How could Crowe’s painting depart so considerably from past visions? McInnis sheds light on this question with a detailed history of image production. To understand Crowe’s painting, McInnis suggests that we focus not simply on pictorial conventions but also on eyewitness documentation. She suggests, in other words, that we follow Crowe on his trip through the United States. Crowe did not initially travel to America to depict slave markets. Rather, he came to America as the secretary for the lecture tour of family friend and famous author William Makepeace Thackeray. From the fall of 1852 to the spring of 1853, they traversed the eastern seaboard. They stopped for Thackeray to speak in cities such as Boston, New York, Richmond, Charleston, and Savannah. En route from Boston to New York, Crowe purchased a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He later remarked that Stowe’s depiction of American bondage “properly harrowed” him (19). McInnis suggests that Stowe’s novel likely fueled Crowe’s desire to see the trade in person.

One morning in Richmond, Crowe read the newspaper over breakfast. He noticed advertisements for local slave sales, and set out to see them in action. Crowe made multiple sketches in different auction rooms, including the picture he would later turn into Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia. Later that day, Crowe stumbled upon a different scene at the Petersburg-Richmond railroad depot: a group of slaves, recently sold, boarding a train. Crowe returned to Britain and soon painted that event in Going South: A Sketch from Life in America (1854). McInnis stresses how Crowe produced distinctive work precisely because of his presence in Richmond: he based many of his subjects on first-hand encounters with the slave trade. She further points to how Crowe’s on-the-ground experiences shaped his aesthetic choices, noting, for example, reportorial details in Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia, such as the stove near the women and the man’s forgotten hat on the floor. McInnis reveals the particularity of Crowe’s visual work through an attention to eyewitness artistry.

McInnis situates Crowe’s actual journey and his art within a broader web of the people, practices, and places that constituted the slave trade. Using historical studies alongside her own work with slave narratives, travel accounts, and traders’ account books, McInnis discusses trade routes and business practices as well as the everyday meanings of sales for traders, masters, and slaves. Readers will benefit from her spatial analyses, which use detailed maps to show how auctions were integrated into the broader landscapes of cities such as Richmond. By encircling Crowe in the multiple contexts of the trade, McInnis demonstrates how he and other artists only conveyed certain aspects of this human tragedy. Crowe pictured auction rooms but did not visualize the Richmond slave jails of Robert Lumpkin and Solomon Davis. McInnis illuminates how Crowe’s painting showed emotional tension but not the cruel conditions of these other waiting places.

In the final chapter of the book, McInnis follows Crowe back to England. She focuses on the display and reception of Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia. In doing so, McInnis advances our understanding of how outsiders experienced the domestic slave trade and shaped perceptions of it. Historians have stressed how actual encounters with the slave trade sharpened abolitionist agendas:William Lloyd Garrison, for example, increasingly assailed the trade in print after he saw it in action in Baltimore. McInnis shifts our attention. She takes us from the pages of northern print culture to the walls of a London museum, from American radicalism to British high culture, from the written to the visual. Moreover, she offers strong evidence for Crowe’s artistic breakthrough. Reviewers lauded the reportorial qualities of Crowe’s work and the different emotions expressed by the waiting slaves. One critic claimed that the painting “secures sympathy.” For this reviewer, the work offered a “literal and faithful transcript from the life it represents” (209). Meanwhile, a writer for the Art Journal praised Crowe’s painting for “successfully and discriminately representing the inward actuality and outward expression of phases of mental thought and human passion” (211). McInnis persuasively reveals how Crowe’s transatlantic image-making stoked sympathy amidst this elite crowd as the Civil War began.

While McInnis offers a welcome addition to the study of visual culture in the Civil War era, her book also raises questions about the historical significance of Crowe’s painting. Readers might wonder how Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia lingered in British (and perhaps American) politics and culture, or why it failed to do so. McInnis ends her narrative with art reviews. She turns in her epilogue to examine postbellum representations of the American slave trade. A broader analysis of “reception” would explore the question of whether antislavery proponents thought about and used Crowe’s painting during the Civil War. Did British activists discuss Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia as, McInnis notes, they had done for Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave? If not, why? As it stands, McInnis’s use of “Abolitionist Art” in the subtitle describes Crowe’s politics in the mid- to late 1850s, and the painting he created. We are left to wonder whether this image offered too radical a vision for the radicals of their time to effectively politicize in words and images.