Face Value

George Washington and portrait prints

In 1880, William Spohn Baker, who forged a minor career as a collector and cataloguer of Washingtoniana, published what was at the time the definitive guide to the engraved portrait prints of George Washington. It was no small task. Less than a century after the founding father’s death, portraits painted during and even after his lifetime had generated more than four hundred engravings whose makers could be identified; those engravings in turn had generated thousands upon thousands of prints. Some were book illustrations, incorporated into histories and biographies; others were sold as stand-alone images, suitable for framing or pasting into scrapbooks. After combing through seventeen collections, including his own, Baker classified the prints first according to the painter responsible for the original portrait and then according to the engraver. As he explained in the book’s preface, he tried his best to weed out the prints that were “copied from no authentic original” and to distinguish the “rare,” the “very rare,” and the “extremely rare” from the ordinary.

Although Baker occasionally noted the artistic merits of the original paintings, he had little to say about the engravings per se. And he had almost nothing to say about the face they depicted. Baker’s “Washingtons” were valued not as art but as Americana. The images did not exemplify aesthetic ideals so much as document national character. And his book was pitched at the connoisseurs and collectors who were beginning to work patriotic objects into their shopping lists. The Engraved Portraits of Washington was a primer in authenticity for men who could recognize a print of Washington’s face but who needed help determining its market value and identifying its painted progenitor. Certainly, Baker began his book with the obligatory paean to the nation’s “father”: Washington’s portraits held unparalleled “interest and significance.” Even the flimsiest engraving could convey “the nobility of his character, the dignity of his manhood, his truth and patriotism.” But the purpose of his book was not to remind readers of these facts. It was “compiled simply as a Text-book for the Washington collector.” Baker, then, was concerned with the authenticity of the artifact not the authenticity of the figure represented on it. But “authenticity” is a moving target. And the citizens who purchased the portraits that eventually found their way into Baker’s collection were far less sanguine than he about the authenticity of the face they saw looking up from the printed page.

Questions about the authenticity of Washington’s likenesses initially emerged when he attained international renown as commander in chief of the Continental Army and “fictitious portraits” found their way into the marketplace. Capitalizing on Washington’s celebrity status, confidence-men-cum-artists unloaded bogus prints on unsuspecting consumers by sticking the head of some other person (real or imagined) atop a suitably dressed and posed body. The most famous of the fictitious portraits, the so-called Campbell engravings, used various military props along with the tagline “Done from an Original Drawn from the Life by Alexander Campbell of Williamsburg in Virginia” to authenticate themselves. Variations of Campbell’s fake likeness were published in London between 1775 and 1778 and seem to have circulated mostly in Europe, although at least a few made their way back to the United States. One was presented to Washington himself, who wryly observed that the commander in chief appeared to be a “very formidable figure [with] . . . a sufficient portion of terror in the countenance.” The Campbell engravings became so well known that more than one hundred years later W. S. Baker included them in his catalogue of “authentic” portraits. They may have been fakes, but they were famous fakes that had earned a place in history and that merited some attention in the collector’s market.

After the Revolution, fictitious portraits had mostly been supplanted by prints taken from the work of painters like Charles Willson Peale, John Trumbull, and Pierre Du Simitiere. If it was still possible to find the head of, say, John Dryden masquerading as George Washington, it was far more likely that Americans would encounter an image that bore some resemblance to an actual commissioned portrait. But the growing availability of “authentic” portraits—that is paintings that George Washington actually sat for or the paintings and prints that were copied from them—did not dispel questions about authenticity. On the contrary, the proliferation of likenesses that claimed some connection to life portraits exacerbated concerns about authenticity, about the relation between pictorial representation and physical reality. This unease surfaced most regularly in relation to engraved prints, the most widely disseminated form of likenesses.

Before Washington was elected president, even authentic portrait prints tended to rely on a variety of devices, not only to convey his status and to locate him in history, but also to authenticate the image itself, to demonstrate that the engraved figure really was George Washington. In Joseph Hiller’s 1777 engraving, Washington is announced by his uniform, by the military props to his side, by the smoke and flames rising from Charlestown in the background, and (not least) by the conspicuous label announcing the officer’s identity. Subsequent prints introduced and elaborated the emblematic vocabulary—liberty pole and cap, oak branches, laurel wreaths—that would come to characterize Washington’s early graphic portraits and to symbolize the qualities that Americans wished to associate with the nation. Those same props and ornaments also served to identify the subject as George Washington, especially for viewers who had never seen either the man or a commissioned portrait.

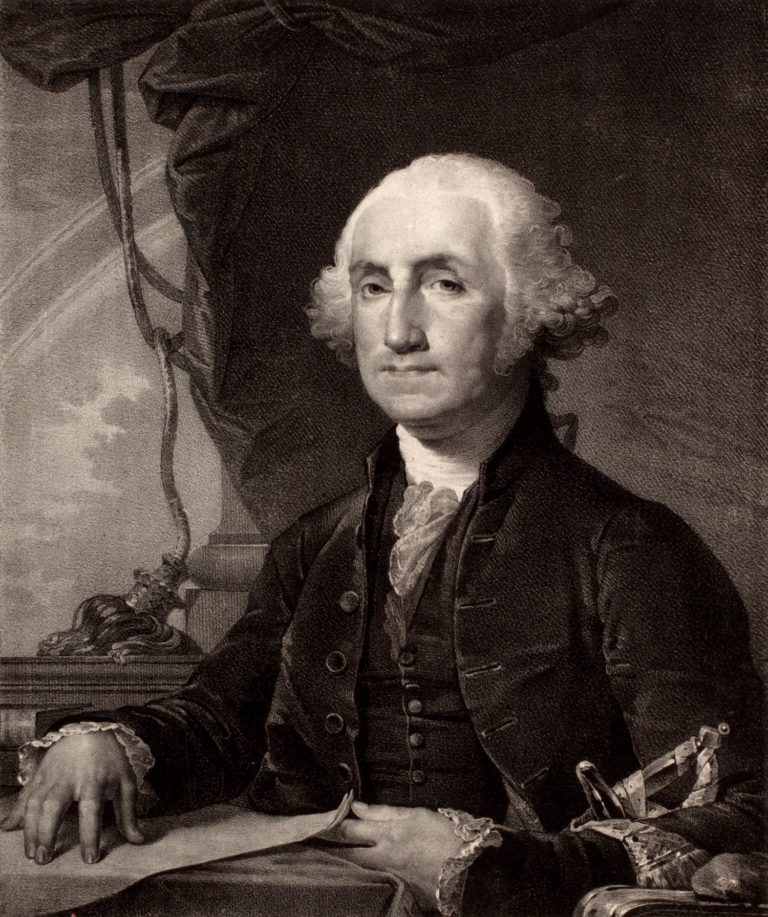

But after Washington’s inauguration as president of the United States in 1789, the military props that had once signified his identity and status began to fall away. Rather than depicting a military officer, saturated with national and historic significance, portraits increasingly depicted only the bust, relying on the painted or engraved face to perform the work of identification and authentication. This shifting emphasis coincided with a new, romantic style of portraiture. It also reflected the economics of the art market: it was far less labor intensive—and therefore less expensive—for a painter or engraver to render a head than a full figure posed against an elaborate background. And the simpler format owed much to the absence of an established set of presidential props. Monarchs, soldiers, sea captains, and even ordinary gentlemen had their defining garments and other material accoutrements. But, as the art historian Wendy Wick Reaves has observed, with no comparable signatures for republican statesmen, engravers and printmakers generally avoided the issue altogether by focusing on the bust.

The tight focus on Washington’s face that dominated his portrayal during his presidency and after also signaled the equation of man and office. We have long recognized the extent to which eighteenth-century Americans conflated Washington with the presidency and even with the federal union. More recently, we have begun to understand how important visual perception was to this fusion. To see Washington was to know him. To see Washington was to remember America’s revolutionary past, to realize its republican future, to participate in the cult of republican sensibility that helped bind the new nation together. Like levees and parades, portrait prints played a critical role in these intellectual and imaginative processes, offering large numbers of Americans the chance, in the painter Benjamin West’s words, to “see the true likeness of that phenomenon among men.”

Presidential portrait prints thus raised the stakes for authenticity at the same time that they narrowed the locus of authenticity to George Washington’s face. But which face was that? Was Washington best represented by the distinctive oval heads painted and engraved by Charles Willson Peale? By Joseph Wright’s aristocratic profile, with its aquiline nose, high cheekbones, and pointed chin? By the boxy forehead and squared off jaw that distinguish Gilbert Stuart’s canonical images? However formulaic they may be in composition, portrait prints reveal a striking variation in their most critical element—George Washington’s face. And this vexing variety was only exacerbated by the growing market for portrait prints, which encouraged artists and engravers of varying tastes and abilities to produce copies of copies of copies. All Washingtons were not created equal.

Certainly that was the conclusion of Johann Caspar Lavater, who ended the 1789 English edition of his Essays on Physiognomy with a discussion of Washington’s character as revealed in portrait prints. Analyzing a print based on Edward Savage’s extremely popular face, Lavater detected “probity, wisdom, and goodness.” So far, so good. But closer examination revealed that if the forehead demonstrated “uncommon luminousness of intellect,” it lacked depth and excluded penetration. Worse, the eyes possessed “neither that benevolence, nor prudence, nor heroic force, which are inseparable from true greatness.” He could only conclude that “if Washington is the Author of the revolution . . . the Designer has failed to catch some of the most prominent features of the Original.” Far more promising, Lavater suggested, was a sketch based on one of Trumbull’s likenesses, which conveyed the qualities that Washington was most celebrated for: “valor . . . moderated by wisdom” and “modesty exempt from pretension.”

In an era when a likeness was not a more or less accurate representation of an individual face but a map of character, getting Washington’s face right was no small matter. Accordingly, artists and engravers competed not only to produce the best likeness but to convince a buying public that they had done so. As early as 1787, for example, Charles Willson Peale advertised a mezzotint portrait of “His Excellency General Washington,” deemed by unspecified authorities as the “best [likeness] that has been executed in a print.” Several years later, advertisements for a medal based on Joseph Wright’s profile described the product as a “strong and expressive likeness,” “worthy of the attention of the citizens of the United States of America.” Potential buyers did not have to take the designer’s word; they need only read the endorsements of four prominent citizens who vouched for the designer’s skill. In 1800, an advertisement for a print based on Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait quoted a magazine review to make the claim that “in point of resemblance, [the image is] said by those who have seen the General, to be uncommonly faithful.” That same year, engraver David Edwin described a small, cheap copy of Stuart’s Athenaeum portrait as the “best Likeness of the Celebrated Washington which has ever been published.”

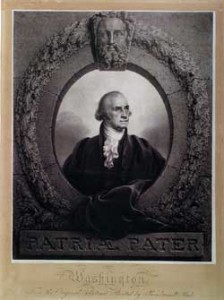

No one worked harder to stake a claim for authenticity than Rembrandt Peale, the second surviving son of artist, museum entrepreneur, and patriot Charles Willson Peale. Extravagantly ambitious, Rembrandt Peale viewed himself as the scion of the nation’s first family of art and Washington’s likeness as his patrimony. By the early 1820s, he had settled on a portrait of George Washington as the vehicle most likely to stabilize his finances and secure his place in art history. While Peale intended for the original painting to be purchased by Congress for display in the Capitol, he also anticipated selling painted and printed copies to an infinite number of individuals and institutions. The result was the magisterial Patriae Pater (1824), a composite likeness culled from the artist’s assessment of extant life portraits and his own memories of the first president. (The president sat for the adolescent Rembrandt as a favor to his more famous father.) Peale aspired to paint the definitive Washington, unseating Gilbert Stuart’s enormously popular Athenaeum portrait in the process. The magnitude of his ambition is suggested pictorially by the massive, trompe l’oeil stonework “porthole” that encases Washington’s bust and gives it a monumental permanence. Peale’s intentions were also announced by the twenty-page advertising brochure that publicized both the original portrait and the copies that he almost immediately began to paint, print, sell, and exhibit. Cataloguing the strengths and weaknesses of one Washington or another and reminding readers that he was one of the few painters still living to have seen the great man, Peale relentlessly built a case for the superiority of his own rendition.

But prospective buyers (in Congress and elsewhere) didn’t have to take his word for it: the pamphlet concluded with the endorsements of eighteen political luminaries who had seen Washington incarnate. For men like John Marshall, Bushrod Washington (George Washington’s nephew), and Andrew Jackson, Peale’s image served as a point of departure. It invited them to recall Washington in battlefields, state houses, and drawing rooms; it compelled them to reflect upon the character they saw in the man’s features and expression. Almost to a one, they confessed that they knew little about art, although many reported seeking out multiple likenesses of Washington. Instead, each positioned himself as a connoisseur of Washington’s face. They recognized the man portrayed on canvas because his features were permanently lodged not only in their minds but also in their hearts: they recognized the President in the “porthole” because of the image’s “effect upon my heart,” because it inspired a “glow of enthusiasm that made my heart warm.” If these remarks testified to the verisimilitude of Peale’s portrait, they also lent credibility to Peale’s claims about the sheer power of Washington’s face. “Nothing can more powerfully carry back the mind to the glorious period which gave birth to this nation,” he wrote, “nothing can be found more capable of exciting the noblest feelings of emulation and patriotism.”

Peale’s brochure was more than one man’s self-aggrandizing hyperbole. Among artists who had painted Washington from life, the deep preoccupation with authenticity went well beyond a workmanlike desire to meet customary standards for “accurate and pleasing likenesses.” Gilbert Stuart so fetishized the authenticity of his canonical Athenaeum portrait that although he copied it endlessly, he refused to complete it. As he explained, it would be “more valuable as it came from his hand in the presence of the sitter” than it would be if finished, “for by painting upon, it would be more or less altered.” The unfinished canvas, to say nothing of its painted and printed copies, suggested the moment of painterly creation and the proximity of the sitter. Even painter-cum-writer William Dunlap, who described his own copies of Washington’s likeness as “cash,” vividly remembered the first time he glimpsed “the man of whom all . . . wished to see” and the electrifying moment when Washington set eyes on him: “It was a picture.” The moment and the “picture” lingered at the edges of his mind, ready to be called forth by a “true” likeness of Washington; in his three-volume history of American art, Dunlap took pains to comment on the authenticity of every Washington produced by the many painters, engravers, sculptors, and wax modelers whose careers he chronicled. Like Peale, Stuart and Dunlap acknowledged the power that emanated from Washington’s face even as they maneuvered to profit from it.

Well into the nineteenth century, some Americans continued to believe that an authentic portrait of Washington, be it an oil painting, a print, or a bust, had the power to reawaken and even create powerful sentiments about the founding father and by extension, the republic itself. But the proliferation of likenesses, authentic and otherwise, registered more than a desire to forge some connection with the man himself, more than patriotic commitments or national spirit. The Washingtons that graced canvases, book illustrations, print collections (to say nothing of crockery, signage, jewelry, and even handkerchiefs) also registered an expansive market. And in the market, the authenticity or accuracy of any particular Washington took on a different set of valences altogether.

On the one hand, the public’s interest in Washington merged with the culture of refinement, which depended upon the nexus of aesthetics and consumption. Deploying Washington’s likeness to demonstrate a capacity for connoisseurship, some men and women shifted their preoccupation with authenticity from the face to the print proper. Consider the Port Folio’s snippy dismissal of English engraver James Heath’s full-length portrait, the first to be taken from Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait and published immediately after Washington’s death. The original composition had much to recommend it, capturing as it did the “union of body and soul.” But Heath’s print was overpowered by the “wire-work” lines that encased the President’s body in a “suit of net-armour,” trapping him beneath a mass of “wicker work.” At issue was not the accuracy of the likeness, much less its ability to rekindle strong feelings about the dead man or the nation, but the quality of the image as an image. Bad art, the critic suggested, could trump even the noblest founder.

On the other hand, the market could chip away at the very notion of “authentic” representation. That was the case in 1814, when Joseph Delaplaine began to solicit subscriptions for what would become the Repository of the Portraits and Lives of Distinguished Americans. Acknowledging widespread disagreement about the best likeness, Delaplaine graciously promised to include two portrait prints of Washington, one taken from Stuart’s Athenaeum portrait, the other from Houdon’s bust. In this way, the author purred, he could “render universal satisfaction.” One man’s true likeness was another’s awkward facsimile. But so long as both men purchased the Repository, the differences hardly mattered.

By the time William Spohn Baker set about sifting his way through George Washington’s engraved portraits, the capacity of those images to inspire individual virtue and invoke national destiny had become a cliché, albeit a mandatory one. Baker himself invoked the storied resonance of an “authentic” or “accurate” likeness only to sidestep it, to assure readers that he was interested only in providing a “Text-book” for collectors. The didactic, even transformative, power that Americans had once sought in Washington’s face had been eclipsed by partisanship, capitalism, sectionalism, and civil war. Like the republican project it symbolized, Washington’s likeness had become the stuff of history. But the power of those “authentic” Washingtons had also been diminished by their ubiquity, by their commodification, by the very images that Baker collected and compiled.

Further Reading:

William Spohn Baker’s catalogue was published in The Engraved Prints of Washington (Philadelphia, 1880). To trace the proliferation and circulation of Washington’s likeness in a variety of media, see William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts in the United States (New York, 1834); Wendy Wick Reaves, George Washington: An American Icon: The Eighteenth-Century Graphic Portraits (Washington, D.C., 1982) and Noble E. Cunningham Jr., Popular Images of the Presidency from Washington to Lincoln (Columbia, Miss., 1991). On the Patriae Pater, see Rembrandt Peale, Portrait of Washington (Philadelphia, n.d. [c. 1824]). The discussion of Peale’s life and work is Lillian B. Miller’s In Pursuite of Fame: Rembrandt Peale, 1778-1860 (Washington, D.C., 1992).

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Catherine E. Kelly teaches history at the University of Oklahoma; she is currently a fellow at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

![His Excel. G[eorge] Washington, engraved by John Sartain in 1865, after a 1787 engraving by Charles Willson Peale. Published in Horace W. Smith, Andreana (Philadelphia: 1865). Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/7.3.Kelly_.2-231x300.jpg)

![Washington. Unidentified engraver after Gilbert Stuart. (Philadelphia, [mid-nineteenth century]). Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/7.3.Kelly_.4-205x300.jpg)

![[George] Washington. Drawn by J. Wood from Houdon's bust. Engraved by Leney. Published by P. Price, printer, ca. 1815. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/7.3.Kelly_.6-214x300.jpg)