Faith in the Ballot

Black shadow politics in the antebellum North

On July 22, 1832, the trustees of Philadelphia’s “First Colored Wesley” church voted on an issue roiling the congregation each and every Sunday: the segregated seating of men and women. Hoping to reduce crowding outside the church, where men anxiously waited for women after services, Wesley trustees put forth a motion “that the women and men sit together for a time to try whether it will not do much towards keeping a mob from before the church.” Congregants and trustees had already debated the matter for a month, and so the decision to adopt the resolution was rendered with all the seriousness of a Supreme Court ruling. By a vote of five to four, church trustees would experiment with mixed seating.

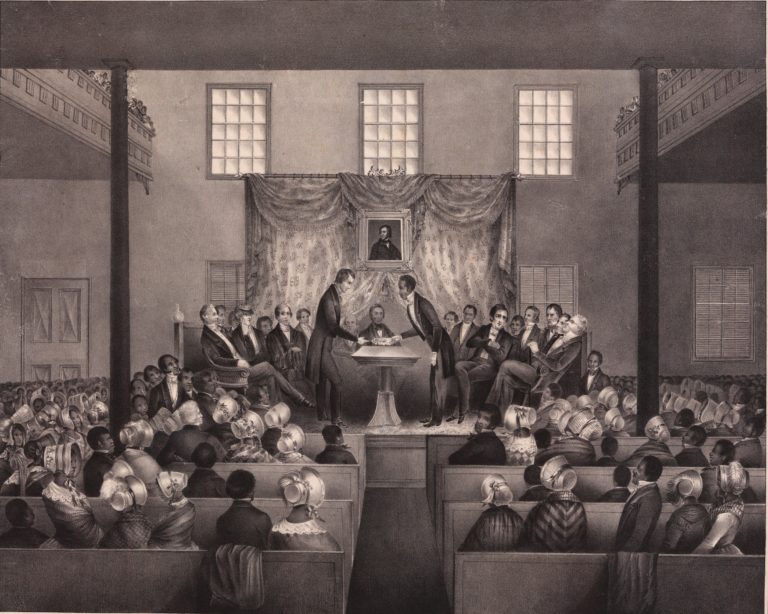

While this vote offers an exciting range of interpretive possibilities—particularly about gender relations in early black churches—it also offers a window into the world of black shadow politics in the antebellum urban North. Although shadow politics has traditionally been defined by sociologists as an alternate universe of political activity (a liminal space in which powerless people act in place of and in conscious opposition to prevailing political practices and norms), I would like to extend its meaning to include the creation of parallel black political practices that both challenged racialized American political institutions and, at the same time, lay claim to core elements of those institutions. From the first freedoms of postrevolutionary society to antebellum disfranchisement in virtually every northern state, black communities created a vibrant universe of political activities that existed just below the more formal stratum of mainstream civic politics. In community organizations, educational institutions, and autonomous churches, free blacks practiced politics in ways that both shaped their daily lives and echoed the practice of democracy in the broader civic culture. Particularly in Philadelphia, where northern emancipation took root earliest and the free black community grew fastest (from under two thousand in the 1780s to nearly twenty thousand by the 1850s), localized voting, electioneering, and constitution making were a constant part of African Americans’ autonomous political culture. And no single institution offers a better perspective on this black shadow politics in Philadelphia than the church. In this autonomous space where African Americans exerted control, free black men and even women exercised rights unknown to them in the broader civic sphere—voting on referenda, running ballot initiatives on a wide array of issues, and electing leaders. Such elections, it should be said, were no isolated affairs. In electing specific church leaders, African Americans were also often selecting figures who could influence elections in the wider community through carefully placed campaign pledges.

Of course, questions abound about black shadow politics and voting rituals in Philadelphia churches. Did black suffrage in these sacred spaces exemplify a syncretic brand of political behavior (one that melded African notions of communalist politics and values with those of Anglo American-style written constitutionalism and individual voting rights)? Or did it signify a commitment to autonomy and self-determination? Does this emerging faith in the ballot among northern urban black churchgoers help explain the evolution of African American democratic practice itself? Finally, where does Philadelphia’s record of black church voting fit in antebellum political history writ large?

These questions first struck me a few years ago in the basement of Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel Church, where a magnificent example of black shadow politics sits in the back of the Richard Allen Museum. In a small protective case, a nineteenth-century voting machine sits rather majestically amid other examples of Bethelites’ political activism (a picture showing AME bishops awaiting the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education hangs nearby). The wooden machine affixed images of candidates for church office above a row of slots. Congregants voted by placing marbles in the hole of the candidate of their choice. Although the machine may have been a product of mid- to late-nineteenth-century church life, it fits clearly into a long history of voting at Bethel—a history dating to the church’s eighteenth-century beginnings. Probing other Philadelphia church archives, I discovered a plethora of examples of black church voting during the early republic.

This stratum of political activity does not rate much coverage in the scholarly literature of either black institution building or American civic politics. Indeed, despite the proliferation of scholarly work on northern emancipation and early black freedom struggles, northern black voting itself remains a marginalized topic. Part of this has to do with the limited amount of primary source material on black votes in the civic realm. Julie Winch’s magnificent biography of Pennsylvania black leader James Forten delves into every possible aspect of his financial life and social relations—yet Winch herself still doesn’t know if perhaps the wealthiest black man in early national America ever cast a vote in any local, state, or national election! Of course, there is scattered evidence that blacks voted in parts of the North and even the South. But the paucity of black civic electioneering material explains why historians such as Glenn Altschuler and Stuart Blumin have declared that free blacks were essentially invisible political actors in the North.

In fact, early northern black church voting may be the missing link in our understanding of black political consciousness and civic mindedness. The beginnings of a modern black politics occurred in autonomous (and quasi-autonomous) northern churches, where the practice of politics—holding elections and referenda, establishing polling places, and running for office—occurred unimpeded. Black congregants and communities believed that grass-roots voting conferred both real and symbolic power—real in that it allowed African Americans to exert control over their internal operations, symbolic in that the franchise was part and parcel of a larger struggle for black citizenship and equality. If African Americans could demonstrate a nuanced understanding of political practice in their own churches, then they could argue for inclusion in civic elections locally and nationally. Black leader Robert Purvis made this link clear in his 1838 “Appeal of Forty Thousand,” which adamantly objected to disfranchisement of Pennsylvania’s black population that same year. Declaring that “we are citizens,” Purvis pointed to the growth of educational and religious institutions throughout the state of Pennsylvania as evidence of blacks’ fitness for freedom. “Our country has no reason to be ashamed of us,” he thundered, for “we are confident [black institutionalism shows that] our condition will compare favorably” with any other group.

In this sense, political activity in northern black churches was not invisible. Though believing in autonomy and/or outright independence from white religious authorities, black leaders and congregants also displayed their political practices before the public at large as a demonstration of the rights of citizenship. The plethora of written constitutions—and their references to internal electoral procedures—produced by black churches and reform organizations before the 1830s is a stunning testament to the hope that northern whites would recognize in black political conduct a fitness for freedom.

What forms did early black church elections take? The historian Elsa Barkley Brown has usefully divided postbellum southern black political activity into internal and external modes—those that relate to inward and outward political contexts, respectively. Black Philadelphia’s internal world of church politics occurred in a nonpartisan political context—there is little evidence of party labels infiltrating church life (though clearly many early black northerners favored antislavery Federalists and Whigs). Politics and electioneering operated at the grass-roots level and (for the most part) in the absence of white political figures, parties, and institutions. In terms of mechanics, shadow politics revolved around three main types of elections or votes: referenda, which dealt with specific issues of concern to the entire congregation (disposal of church property, for example); trustee and ministerial elections, which allowed congregants to establish the layers of church leadership on an annual basis; and trustee votes, which revolved around the daily business of church operations (assigning acting committees to deal with various problems, paying bills, determining and interpreting church procedure).

Wesley Church’s 1832 vote on integrated pews was an example of the third type of internal initiative: trustee votes. Here, elected church officials determined policies and procedures in accordance with the religious body’s constitution and/or act of incorporation. In this realm of political activity, representative democracy, and not grass-roots voting, determined day-to-day church affairs. Yet this seemingly republican-style politics did depend on broader congregational concerns, with a new slate of annual elections occurring in most Philadelphia churches. In addition, black church trustees functioned very much in the tradition of African elders, who took the pulse of the community before rendering decisions.

In October 1828, Mother Bethel offered a terrific example of the first type of vote: a referendum open to the whole congregation. After a running dispute with Wesley (whose leadership was comprised of Bethel dissidents) had left church coffers low, Bethel trustees put forth a referendum on selling extraneous church property, excluding the main church, key rentals, and burial grounds. On October 15 of that year, the vote occurred, with trustees stipulating that the church constitution required that “two thirds of the male members over 21” must vote for the resolution to pass. Judges and witnesses certified the election’s constitutionality. Moreover, each of the over one hundred voters—including over sixty people who had to sign with an X—”testif[ied] our full and free consent” in voting for the measure (which easily passed).

In many ways the second initiative—elections of church leadership—offers the most consistent view of black ballot initiatives. Each of Philadelphia’s major independent black churches held regular votes for church leadership by the early nineteenth century. First African Presbyterian, formed in 1807 by a former Tennessee slave named John Gloucester, held perhaps the most electrifying series of congregational votes between 1822 and 1823, when members were asked to determine the fate of ministerial succession. Founder Gloucester’s untimely death in 1822 left the growing church (numbering over three hundred members) bereft of leadership. Congregants debated two possible candidates for minister: Gloucester’s son Jeremiah, a youthful but promising preacher, and Samuel Cornish, a member of the New York presbytery who would soon become coeditor of Freedom’s Journal, the first African American-run newspaper. At a meeting presided over by a white minister (African Presbyterian remained within the fold of the synod, and white preachers took a special interest in the fate of this inaugural black Presbyterian church) on May 8, 1822, congregants voted first on whether or not to postpone this pivotal election. According to William Catto, the first historian of African Presbyterian and a well-known black preacher at the church, the motion to postpone was defeated by a vote of seventy-nine to fifty-three. Deliberations on the new minister then continued. After Cornish’s name had been forwarded as the prospective leader, congregants “proceeded to ballot” for and against him. Cornish’s candidacy was approved by a vote of seventy-eight to forty-eight.

The matter did not end there, however. “To say that this election passed off peaceably,” Catto later reported, “would be more than I can venture to affirm.” For before Cornish was officially offered the ministry by the Presbyterian Church, “warm opposition” among African Presbyterian dissenters made its way to the Presbytery meeting in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. A committee of white ministers visited the church in the fall of 1822, recommending Cornish’s ascension to minister—but a further “minority report” by church dissenters against this action prompted yet more consideration of the matter. Following work by another committee of white ministers in 1823, anti-Cornish congregants offered a petition to Presbyterian leaders “signed by 75 persons…requesting” the formation of their own church. Though Catto argued that fealty to Gloucester’s memory prompted dissenters to oppose Cornish (and nothing more), he was saddened by this result.

Ultimately, the church divided into first and second African Presbyterian congregations (yet a third branch soon formed as well). Despite outward appearances of unruly black congregants, white church officials were impressed with the solemnity and conduct of black voters. No mobbing or rioting had occurred, and congregants agreed to a most American political solution: the creation of different congregations. In fact, white officials celebrated black democracy. “Having heard the parties fully,” one Presbyterian church report declared, “and [having] maturely deliberated on all circumstances of the case…this Presbytery are fully satisfied that the parties which have existed in the first African church are of such a nature that further attempt to reconcile them are in expedient…” Although the formation of the second American party system was still a few years away, the use of “parties” to describe black church disagreements is interesting. White officials seemed to recognize the legitimacy of black differences as well as the utility of “parties” to mediate them. Or as William Catto put it, “as it is in civil communities, so it is in religious ones.” Translation: politics was inevitable, whether in American civil society or sacred institutions. Another translation: African Americans were no different from white citizens. Indeed, while Catto bemoaned the breakup of a sanctified community of God, he also made clear that African Americans understood democratic practice. Writing in 1857, he was perhaps thinking of the lessons such black shadow politics held for white legislators who continued to oppose black re-enfranchisement in Pennsylvania.

A congregational vote over ministerial succession was one thing; annual elections of church leaders were quite another, for they represent a nuts-and-bolts view of black shadow politics. Although not a black mainline church, First Colored Wesley provides the best and most consistent records of black voting behavior in the 1820s and 1830s. Formed in June of 1820 by disgruntled Bethel members who felt that Richard Allen and AME trustees operated with an iron fist and closed books, they established an independent branch of the black Methodist Church—one with an eye towards maximizing democratic practice. Account books and voting records would be open; rotation of trustees, encouraged; affiliation to regional and national Methodist groups, changing depending on terms (the church became part of the New York City AME Zion Connection before coming back into the fold of the white-controlled Methodist Episcopal Church). Wesley held trustee elections annually on the first Thursday after Easter. According to church minute books, a committee of three trustees was appointed to “nominate candidates for [the next] trustee” elections. Like Senators, trustees ran for office on a rotating basis so that new faces would be represented every few years. The elections themselves required further appointments: an election chair, two or three judges at the “polling place” (the church), a secretary to record all the votes. In most of Wesley’s elections, a slate of at least six candidates ran for trustee positions, with the top four vote-getters securing office. After elections were held, trustees then sorted themselves into various offices, including president, vice president, and secretary. Vote totals could fluctuate but were often quite impressive. In April 1828, 91 male congregants voted for a slate of ten candidates. By 1840, over 130 congregants cast votes in annual elections for six or eight candidates. These numbers correlated to perhaps half of Wesley’s male church members.

There was, then, rather widespread male suffrage in Wesley church. By the 1820s, other Philadelphia churches held similarly broad-based votes. Males over twenty-one in good standing for at least a year could vote at Bethel, First African Presbyterian, and First Colored Wesley. In the 1828 referendum on Bethel church property, laborers voted alongside master chimney sweeps and black gentleman.

What about women? Women did not have explicit voting rights according to church constitutions. Yet in key instances they either voted or were considered part of the congregational electorate. In 1807, Mother Bethel congregants—including women—voted unanimously to pass the African Supplement, a document guaranteeing black sovereignty over the church. The vote followed the advice of white lawyers who pointed out that Bethel could overturn a decade-old incorporation act that gave white Methodists control over black church property. Black self-determination would occur only if two-thirds of the entire congregation agreed to the new document. “Both male and female,” Allen proudly asserted in his posthumously published autobiography, supported the African Supplement. Bethel women thus bolstered the church’s political stand against white officials. The 1807 referendum was cited later in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision guaranteeing Bethel’s independence.

While the passage of the African Supplement remains the most striking example of women’s participation in early church politics, it is not the only such case. Indeed, roughly a dozen women had voted with their feet by joining Richard Allen’s departure of segregated St. George’s Methodist Church in the early 1790s. In 1815, women joined male congregants to again confront white preachers who wanted to take hold of Bethel’s pulpit. At Bethel, women were not silent actors.

In fact, these examples of male-female congregational mobilization raise a key question (one that scholars of the postbellum South are more familiar with): were black women consulted by men before casting church votes? Clearly, women were considered key parts of the congregational political and social world. Richard Allen’s second wife Sarah, a former Virginia slave, was often mentioned in early church histories as a helpmate who bolstered the respectable image of the new black church and its leaders in the public realm. This made her a sort of black republican mother, one whose selfless contributions to church success flowed from her belief in the greater good. But women often did more than bolster men’s image. Wesley women raised nearly 40 percent of the total money required to purchase a new church graveyard in the summer of 1838. And at both Bethel and Wesley, as at other black churches, women formed and staffed benevolent and burial-aid societies. Given their fundraising and reform activities, it is not hard to imagine women playing consulting roles with male trustees and voters.

While there are many more examples, it should be clear that Philadelphia’s black churches created a lively political arena—what historian E. Franklin Frazier in a later period referred to as a political “nation within a nation.” What does this shadow political world tell us about broader trends and issues? First, northern black church politics seemed to be defined by two mutually reinforcing, rather than diametrically opposed, sensibilities. On the one hand, black congregants sought to build autonomous power structures that guided Philadelphia’s growing free black community through the vicissitudes of freedom. Political activities at the church level occurred in a safe haven, so to speak, where autonomy and communitarian values flourished. Indeed, one might say that black shadow politics was merely part of a broader history of African American decision making. In reform institutions, autonomous businesses, and churches, African Americans exercised their ability to render decisions that framed their daily lives. This is an important point that should never be lost in any study of black politics during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

On the other hand, though, the creation of that black political world was aimed very much at influencing the American public—that is, legitimizing African Americans in the civic realm as freeman and free-women who understood both the ideals and practice of democracy. A strong community base, in other words, facilitated not merely the retention of traditional ways of understanding the world (communitarianism) but free blacks’ maturing understanding of American democracy itself. In this sense, historians C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya’s famous notion that black church life flowed exclusively from an African-centered “sacred cosmos” needs revision.

Indeed, northern black church politics was not so much a different world as it was a different arena for what Americans everywhere were doing in the early nineteenth century—holding elections, drafting constitutions, using power when and how they could. Black congregants running for church office as well as those voting in church elections believed they were enacting freedom. It was no mere performance to cast a ballot for church leaders; but there was a performative aspect to arriving at the church polls, saluting a black official who certified ballots, and awaiting official election results. The church, then, was a practical space where black men and women could conduct American-style politics in a manner that maximized democracy from below while also demonstrating fitness for freedom to those above. Here, historians of black politics can learn from literary and cultural scholars working on the ritualized nature of performance spaces (stages, marches, and so forth).

Similarly, northern black church elections allowed black congregants to perform the rituals of democracy unadorned. William Catto’s history of the African Presbyterian Church offered a peek into this world of shadow politics by describing how church voting actually occurred. After a committee of five church elders—who themselves were elected for office—met to determine the date and time of the vote for a new church leader, they moved that “the names of all persons entitled to a vote in the election be enrolled in a book, and each name called out as recorded, in order, and each person at liberty to vote as they may think most proper.” True, a white mediator in the form of a Presbyterian official did preside over some of these elections at this one church (it is not clear from the records whether white ministers were always present). Yet Catto highlighted not whites’ presence but blacks’ attention to political procedure—the roll call, tallying of votes, and fealty to a political process. Over a hundred people from the congregation had gathered to hear their names called—thus preventing fraud—after which they voted in a sanctioned event over the fate of the new minister (Catto does not say whether or not this was a secret ballot). Little wonder, then, that Catto’s son, Octavius, became a leading voting rights activist in Philadelphia following the Civil War. He was murdered in 1871 by a white tough who opposed black voting rights. Born in 1839, Octavius Catto lived his entire life as a disfranchised man; he survived only a year beyond Pennsylvania’s re-enfranchisement of black voters in 1870 (and then thanks only to the Fifteenth Amendment).

The second point concerns time frame and historiography. Black church voting in the urban North may ultimately point to the need for a new narrative of black politics. Rather than one that begins with formal disfranchisement in the North in the antebellum era, followed by the flowering of black electioneering in the postbellum South and then a second round of fin de siècle black disfranchisement, we might think instead of the ongoing reconstruction of American politics from the nation’s founding forward in both the emancipating North and slave South.

But the striking thing about the maturation of black shadow politics in the North is that it occurred precisely at the time whites grappled with the political meanings of the first emancipation. Though gradual and disappointing, the wave of first emancipation laws and constitutions appearing in the postrevolutionary North was very much the product of black protest—and very much exploited by black reformers into the nineteenth century. For Richard Allen, James Forten, and Robert Purvis—black Pennsylvanians, all of whom participated in church and institutional politics—blacks would indeed grow from political underlings in need of white oversight to independent citizens. When white citizens in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, and other northern locales realized that African Americans were mobilizing beneath and alongside them as citizens (and not acting as marginalized subjects), they balked, rioted, and ultimately plotted black civic expulsion.

Read this way, early black political history emerges not in reaction to disfranchisement but as the cause of it. Pennsylvania’s disfranchisement in 1838 was in a very real sense a reaction to an emerging black political order that understood the dictates and practice of democracy. It is not surprising, then, that black disfranchisement in Pennsylvania lasted until the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment—and that postbellum black Pennsylvanians called for a dual reconstruction of American political and social life (one which resulted in anti-black violence). There was, in short, no neat division between black political practices in northern churches and the wider political debate over black freedom. We need more histories that recapture the multivalent nature of black political conduct in the antebellum North as well as the post-Civil War South.

Happily, this is a story that scholars are beginning to take up. For now, we may say merely that free blacks in Philadelphia churches, like their colleagues elsewhere in the urban North, did not wait to be enfranchised or disfranchised. Rather, from the republic’s very beginning, they sought to practice politics where and when they could. They had faith in the ballot—and in themselves.

I would like to thank members of a SHEAR 2008 Conference panel on black politics and ideology in the Urban North, especially Elsa Barkley Brown, Erik Seeman, and Erica Ball, for their insightful comments on an earlier version of this essay. Thanks to Dr. Jim Foley and to members of the audience—including James Stewart, Manisha Sinha, Reeve Huston, and Jeff Pasley—who offered great contextual comments and critiques.

Further Reading:

On free black political leaders in Philadelphia, see Richard Newman, Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (New York, 2008) and Julie Winch, A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten (New York, 2002). For a now-classic treatment of black political behavior after the Civil War, see Elsa Barkley Brown, “To Catch the Vision of Freedom,” reprinted usefully as “The Labor of Politics” in Thomas Holt and Elsa Barkley Brown, eds., Major Problems in African American History, vol. 2 (New York, 2000). On antebellum politics generally (and blacks’ invisibility specifically), see Glenn Altschuler and Stuart Blumin’s otherwise terrific Rude Republic: Americans and their Politics in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, N.J., 2000). On black constitutionalism, see James Oliver Horton, “Weevils in the Wheat: Free Blacks and the Constitution, 1787-1860,” in This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, Fall 1985, published by Project ’87 of the American Political Science Association and American Historical Association. And on the use of the term “shadow politics,” see, for example, Elijah Anderson, “Black Shadow Politics in Midwestville: The Insiders, The Outsiders, and The Militant Young,” Sociological Inquiry (January 1972): 19-27.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Richard S. Newman teaches at Rochester Institute of Technology and is the author, most recently, of Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (2008).