Family Albums of War: Carte de Visite Collections in the Civil War Era

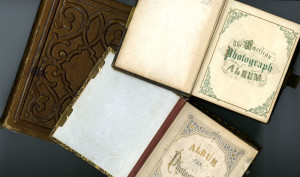

In the A.S. Williams III Americana Collection at the University of Alabama, leather and cloth-bound photograph albums from the 1860s and 1870s line the dark wooden shelves, some dozen in all, small and large, cloth and leather, embossed and plain. At first glance the photographs they contain, called cartes de visites, all seem remarkably similar: pieces of card stock about 2.5 inches wide and 4 inches tall, mounted with albumen images of stiffly posed men and women, hair glossed back, faces anonymously blank. Many of these figures are in fact anonymous, or nearly so, identified only by a scrawled pencil inscription—Aunt Maria, Uncle Paul—or perhaps a line of description on their hidden flip sides. A closer inspection, though, reveals some intriguing narratives: images of young men in uniform next to miniaturized reproductions of popular paintings of pets; a portrait of Napoleon across from a Civil War general; a striking cartoon of Lincoln and Washington in mutual embrace. Though the Williams Collection also owns a rare two-volume edition of Alexander Gardner’s famous Sketchbook of the War, it is in these more modest albums that the domestic narrative of the 1860s and 1870s is written.

Nineteenth-century viewers were just as likely to envision the war through the more personalized lens of the family album as through the battlefield photographs by professionals such as Alexander Gardner and Matthew Brady, which have taken the more prominent place in the historical record. The carte de visite album, which became commercially available just as the country headed into war, was an important means for a domestic middle-class audience to contend with and record their experiences of the Civil War. Literary historian Ellen Gruber Garvey’s assertion that scrapbooks “open a window into the lives and thoughts of people who did not respond to the world with their own writing” is equally true of the carte de visite album. These leather- or cloth-bound albums, accessible to a range of budgets, allowed collectors to arrange small photographs in a personalized mix that often juxtaposed commercially reproduced images of artworks and celebrities alongside the more intimate studio portraits of friends and family members. During the Civil War and Reconstruction periods, this eclectic mix of the public and private included prominent political figures and wartime generals.

Although these albums were common in Northern and Southern middle-class homes, they can be difficult to interpret for historians and family members alike. Identifying the person—or people—who put the albums together can be challenging, as can tracking down information about the sitters. The albums themselves, with their thin and fragile paper pages, are an obstacle rather than an aide to interpretation. Removing the photographs to read the inscriptions on the back cannot easily be done without damaging the paper sleeves. These difficulties often leave key historical questions, such as the precise dating of the albums and the stories behind the images, unanswered.

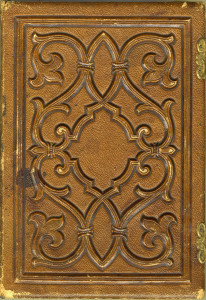

Interpretive challenges aside, many of these albums can nevertheless offer insights into how ordinary Americans from both the North and the South experienced the Civil War. One of the fascinating aspects of these works is the way that they anticipate social media like Facebook and Twitter by mixing personal and popular photographs. Yet unlike these open-form twenty-first-century media, the book structure of carte de visite albums encouraged a compiler to present his or her story with a thought-out beginning, middle, and end. An excellent example of such a narrative arc is the Perley E. Collings Album, a tan embossed leather album kept after the Civil War by a former infantryman. As this volume shows, the micro-history of carte de visite albums, although sometimes all too open to interpretation, can tell us captivating stories that go beyond the history of photography into topics such as the significance of popular art images to daily life, the relationship between the domestic and the battlefield, and the continuing impact of the Civil War on the lives of post-war Americans.

Compilations such as the Collings Album were created with the aim not just of recording personal histories, but also of inspiring general interest. In his book Reading American Photographs, historian Alan Trachtenberg writes that the commercial reproduction of well-known battlefield and camp photographs as cartes de visites, and carte de visite series such as Brady’s Album Gallery “permitted their owners to assemble sequences on their own” as “private panoramas” in personal image albums, creating their own narratives and captions for views of the war. In the case of family albums, such personalization went one step further, as compilers mixed portraits of family members with political and sentimental prints. Like so many nineteenth-century documents that to modern viewers can seem like intensely private things—letters, diaries, scrapbooks—family photograph albums were intended for both private and public consumption. Although recording a personal history, they were placed openly in parlors, inviting friends and acquaintances to browse their pages.

Albums, in fact, were designed specifically to blend the private and public spheres. When bound albums with framed slots to accommodate cartes de visites entered the American market in 1861, Harper’s Weekly called them “galleries of friendship and fame.” Compilers who failed to include this aspect of “fame” in their collections risked falling short of the album’s end goal of public entertainment. For instance, in 1872, a Baltimore trade publication, The Photographer’s Friend, printed an opinion piece criticizing a fictionalized album-keeper, “Miss Domestic,” for arranging an album only with personal photographs, which, like photographs of the family vacation, were guaranteed to bore visitors. In contrast, “Miss Enterprise” successfully entertained guests with an album containing images with more popular appeal, such as pictures of Niagara Falls, American presidents, European royalty, and celebrities such as P.T. Barnum. In other words, the album’s ostensible purpose was to contain and preserve personal images of family members, but in order for it to have entertainment value, it also had to include more general-interest photographs. For Americans in the Civil War and post-war years, such images of general interest most often included prominent participants in the conflict.

Several Civil War-era albums in the Williams Collection show this blending of public and private, but none more clearly than the Collings album. Inscribed on its cover page with the name and home state of its compiler, an infantryman in “Company C. 14th New Hampshire Volunteers,” or the 14th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, as well as 1867, the year of its completion, this album provides more information on its origin than most. But like many carte de visite albums during this era, the Collings album freely mixes the personal portraits that were exchanged between family members and friends with the commercial photographs of popular prints and celebrities that were for sale at photographers’ studios. The resulting juxtaposition of images encourages a personal interpretation of the political and a political interpretation of the personal.

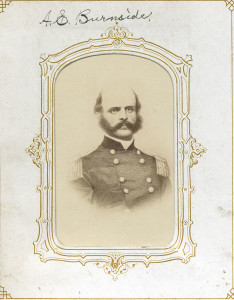

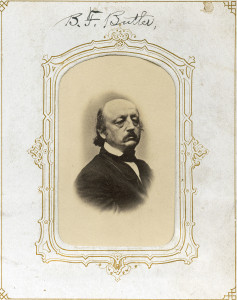

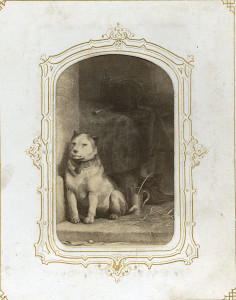

This juxtaposition of the political and the personal is apparent from the first pages of the album. The generic commercial printing of the title page (“The Photographer Album, New York”) is bordered by Collings’ pen inscription of his name and infantry number, announcing a political affiliation and personal identity that continues into the first three pages of the album, with his prominent placement of six major Union figures including Winfield Scott, Ambrose Burnside, and Benjamin Butler. These images are immediately followed by two photographs of popular paintings by Sir Edwin Landseer, “High Life” and “Low Life,” first exhibited as companion works in 1831. The former of these shows the profile of an elegant deerhound in a comfortable interior setting, leaning against the seat of an upholstered chair. The latter shows a frontal view of a stockier terrier in the doorway of a workshop. The dogs function as stand-ins for their absent owners, the one presumably an aristocratic gentleman, the other likely a butcher. In the context of the Civil War images that open the album, one could read this dichotomy as speaking to a caricatured contrast between North and South: the self-made working man on the one hand, and the degenerate aristocrat of the slave economy on the other. Of course, the Landseer prints were popular, precisely the kind of “images of fame” that album-keepers were instructed to include to entertain their audiences, so a reading that sees the war in these cartes is only one of many possible interpretations.

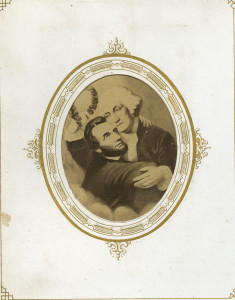

But even taking this caution into account, the placement and juxtaposition of the images in the Collings album and other albums like it suggest certain interpretations over others. Collings’ placement of political and domestic images alongside one another seems to underline the ways that the political became personal and sentimental during this period, a tendency confirmed by the arrangement of the carte print “Washington & Lincoln (Apotheosis)” near the middle of the album. This popular image, several versions of which circulated after 1865, is a reproduction of an anonymous painting that depicts Washington reaching down to place a laurel wreath on Lincoln’s head as the two embrace in a landscape of clouds; in some versions, angels look down upon them. Printed after his assassination, the image paints Lincoln as a martyr, and associates his memory with the more generally accepted and historically distant glory of Washington.

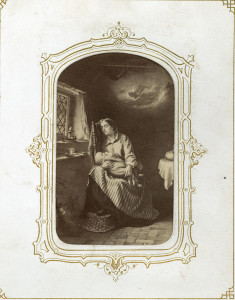

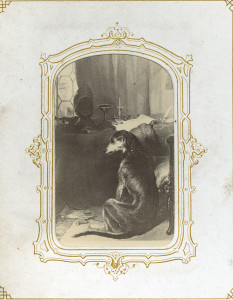

The Lincoln-Washington carte de visite shares a page with a hand-colored photograph of another popular print—an image of a woman with books tucked underneath her arm—and is next to two similar, commercial prints of sentimentalized young women with faraway gazes. Reminiscent of the images that appeared in “books of beauty” in the first half of the nineteenth century, these generic, aestheticized images provide what to us might seem an unexpectedly apolitical backdrop for the Lincoln print. They emphasize the soft focus and the distant gaze in the eyes of both presidents, placing the former president firmly in the context of sentimentality and abstracted idealization rather than more specific political or topical events. Lincoln, Collings’ arrangement stresses, has already moved by this point in the late 1860s to the status of an abstracted ideal, an object of domestic admiration.

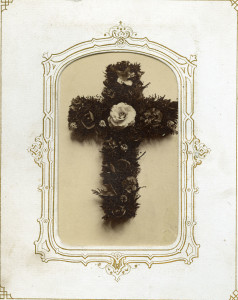

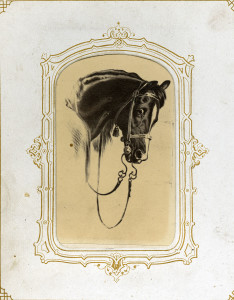

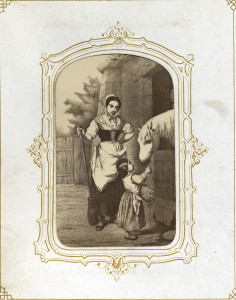

This carefully curated back and forth between the personal and the political continues throughout the rest of the album. The next several pages, for instance, show carte de visite portraits of women captioned as family members or friends, interspersed with illustrations of horses. The pages that follow include images of sentimental paintings of domestic and rural scenes, prominently featuring children, horses, and in two cases, crosses. The crosses—generalized images of Christian piety, but also, of course, death—suggest the place that the war has in these scenes of pastoral life. The horses could also be seen as playing such a double role. On the one hand, they are stock sentimental figures, pictures included among family portraits to interest friends or acquaintances who might page through the album. But their number and repetition—six in all in the course of the volume—seem to speak to their broader significance for the former infantryman who compiled the album. Some of the animals point implicitly to the battlefields on which they played a significant role: one horse, bridled and blanketed, could be an illustrated detail from a battlefield scene. Another, fed a handful of hay by a small child and titled “Confidence,” is a clear agent of a rural domestic education. These images, moving back and forth between the public and the private, the political and the domestic, underline the deeply personal place that the war held in the lives of Americans. By placing generic commercial reproductions in a familial context, compilers like Collings were able to make them speak in the language of an individual.

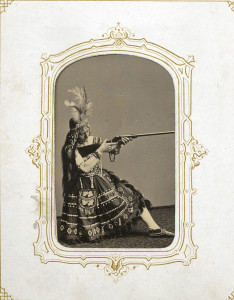

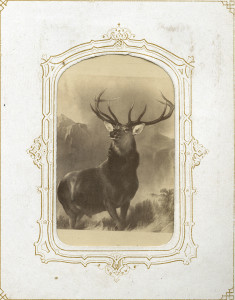

This movement back and forth between the public and the private recurs in striking ways throughout the album, and is perhaps most apparent in a series of commercial portraits that follow only a few pages later. The first set, two hand-colored photographs of popular illustrations, present the conjunction between the domestic and the political explicitly. Titled “Young America,” they depict small children, a girl and a boy, as soldiers, with epaulets, rucksacks, swords, and rifles, directly conflating the domestic and political. A few pages later, the compiler has placed a carte of a woman in moccasins and a leather dress aiming a rifle in the slot to the left of a reproduction of Edwin Landseer’s The Monarch of the Glen, the 1851 painting of a stag that was one of the most reproduced artworks of the nineteenth century. The conjunction of the (Native American) hunter—actually, the actress Marie Zoe, who posed in costume for many popular cartes—and the hunted on this page confirms the care that went into the arrangement of these images. And in light of the other more explicitly political scenes, the hunter’s cocked rifle also seems to allude to the battlefield. Shortly thereafter follows the Lincoln-Washington image, and then a similar juxtaposition of the sentimental and the political on a page containing three sentimental drawing-room illustrations of women alongside of “Emancipation,” a print of a triumphant Columbia surrounded by freed slaves.

If we pull back from an analysis of the relationship between individual images, we can also see a clear narrative progression in the album’s overview. The volume begins with a series of public Civil War notables, moves through images that are both domestic and battle-oriented, and then culminates in the war’s end, as seen through the cartes of “Lincoln & Washington (Apotheosis)” and “Emancipation.” The compiler has followed these images with a carte of Thomas Nast’s famous 1864 political cartoon “Compromise with the South” to reinforce this general progression. As the Unionist’s grim imagination of what George McClellan’s political platform might promise (as well as the image whose widespread reproduction aided in Lincoln’s re-election) this print, like the earlier two, marks the approach of war’s end. Taken together, these closely grouped images of apotheosis, emancipation, and re-election signal the war’s imminent conclusion in Collings’ curated world.

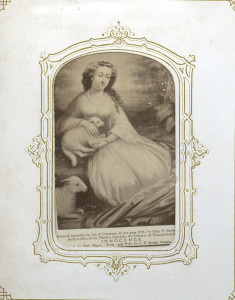

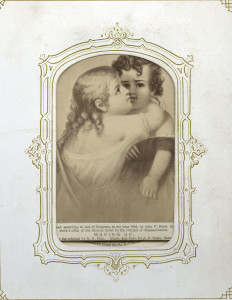

The pictures that follow mark the hardship and hope of the early Reconstruction period. A hand-colored image titled “Past, Present, and Future” shows a grandfather, mother, and two children in reflective poses, the grandfather with downcast eyes. In the context of the album’s Civil War imagery, this commercial print of a family group without a father figure seems to suggest the emotional impact of the Civil War dead. On the next page, two sentimental portraits of children point to the material straits of such absences during Reconstruction. The first, from J.P. Soule’s drawing “A Cold Morning,” shows two young children, a boy and a girl, huddled together, while the next, “Homeless,” from a painting by G.G. Fish, is a yet more literal image, showing two barefoot girls with pensive expressions in a rural setting. On the next page, Collings has counter-balanced the bleak tone of these cartes with pictures of uplift: the first, “Innocence,” depicts a woman caressing a lamb, a symbol of peace; the next, “Making Up,” shows a young boy and girl in an embrace that suggests a mutual resolution, a counterpoint perhaps to Nast’s “Compromise with the South” that imagines a reconciliation between North and South.

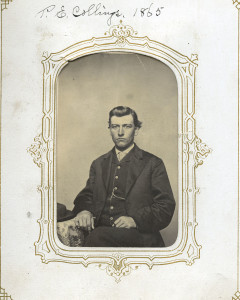

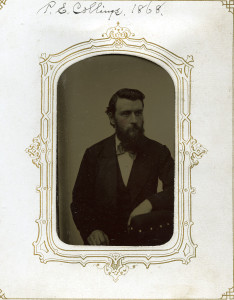

Finally, just before the cartes of Andrew Johnson and Benjamin Butler that conclude the album, Collings has placed the only two images of himself. The first is a carte of a clean-shaven young man, dated 1865, and the next a tintype of a sober, bearded man from 1868. The two photographs considered side by side mark an evolution, a transition from soldier to civilian life, from a slightly dazed youth to a composed, well-groomed man capable of narrating his experience of the war as a series of personal and political images. Appearing as they do at the end of the album, these before and after shots can be read compellingly as records of another progression, not of the war, but of the soldier’s return to domestic life through the creation of the very photograph album that the reader has just perused.

These final images suggest some of the ways that these curated albums differ from the contemporary social media to which they are often compared. While both the historical and the contemporary media allow users to present themselves through images of friends, family, political figures, and celebrities, the carte de visite album encouraged an arranged narrative of an individual’s experience, with a designated introduction and conclusion. While the confines of the album’s content are dictated by the somewhat arbitrary outlines of the commercial manufacturer, these confines nonetheless impose an organization. Some users chose to ignore this structure, but others were guided by it, as P.E. Collings’ album shows. His decision to conclude the album with his own images suggests an understanding of the arc of history as defining the arc of personal lives, marking experiences in ways that the camera and the illustrated image could collaborate in documenting.

Further Reading

Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford, 2012).

Lara Perry, “The Carte de Visite in the 1860s and the Serial Dynamic of Photographic Likeness,” Art History 35.4 (2012): 728-749.

Elizabeth Siegel, Galleries of Friendship and Fame: A History of Nineteenth-Century American Photograph Albums (New Haven and London, 2010).

Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Matthew Brady to Walker Evans (New York, 1990).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Christa Holm Vogelius (@christavogelius) is assistant professor of American Studies at the University of Copenhagen, where she teaches courses on nineteenth-century literature, visual culture, and archival studies. She has also been a CLIR postdoctoral fellow at the University of Alabama, where she worked on digital exhibits in the A.S. Williams III Americana Collection. She is completing a book project on the intersection between nineteenth-century American art description, gender, and literary nationalism.