Fancy History: John Fanning Watson’s Relic Box

Introduction

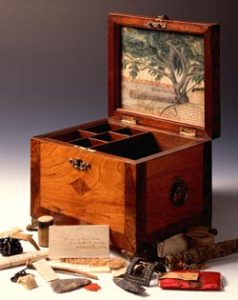

We are immediately skeptical of relic collections like the one made by the early nineteenth-century Philadelphia historian John Fanning Watson (figs. 1 and 2). The box, constructed for Watson around 1823 by an unknown craftsman from the wood of Penn’s Treaty Elm, seems to be just another instance of invented tradition. Its contents—like Queen Elizabeth’s knitting bag—obviously have apocryphal provenances. Watson’s published works, the Annals of Philadelphia (1830) or the Annals and Occurrences of New York City and State in Olden Time (1846), do not hold up any better under scrutiny than his relics. Their anecdotes about the events and customs of the past are similar in fragmentary form and in dubious accuracy to the objects he collected. Susan Stabile sums up modern views of Watson’s work with the comment that his “error-ridden though widely read Annals perpetuated the heroic (and often inaccurate) myths of national memory.” Even his contemporaries, like Dr. James Mease—himself the author of an early account of the city’s history titled The Picture of Philadelphia (1811)—complained that Watson’s collections and writings merely promoted “venerable traditions … as if historical truth were not more valuable than any tradition, however ancient, and gratifying to our national vanity, pride, or good feelings.” Rather than giving us a history lesson, this box seems to owe us an apology for the invented past of virtuous aristocrats and friendly Indians that it inflicts on us.

Yet the box works against our efforts to take venerable traditions and history seriously. Compared with the multivolume works like David Hume’s History of England or Mercy Otis Warren’s History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution that provided Watson’s generation with researched and logical narratives of past human actions, this small box and its miniature contents make history seem like child’s play. Narrative histories of action make us exceedingly conscious of the sequence of events over time. But time plays hide and seek in these small fragments. On the one hand, as critic and poet Susan Stewart points out, when we attempt to describe miniature objects, we descend into an overabundance of detail and confront language’s limited ability to represent a material object. Unlike a narrative sequence of actions, therefore, these objects push us towards a silence that arrests time and encourages contemplation. On the other hand, the arrowheads, buttons, fabric scraps, and pieces of wood in Watson’s box are all remains of larger wholes. Like a memorial lock of hair or the remains of the Coliseum, they reveal that death and relentless physical erosion accompany the passage of time and ultimately reduce an entire world to a few fragments. Because these fragments cheat destruction, they possess a supernatural quality even as they bear witness to the inevitable process of decay. But unlike the Coliseum, Watson’s ruins are small enough to be manipulated, domesticated, and protected from decay in the box. Their overall effect, therefore, is not one of sublime awe at the forces of chaos but of nostalgic delight in a toy-sized past purified of death and putrefaction.

Since these miniature ruins arrest time through play and contemplation rather than narrative action, it is not surprising that Watson’s books and his box all fail to account for change over time critically or logically, either by depicting it as a narrative of birth, growth, and decline or as a Whig account of progress. Instead, Watson, his readers, and his fellow relic collectors used these discontinuous forms to challenge the dominance of narrative in the production of historical knowledge. The fragments cultivate physical delight, emotional attachment, and creative play to make people care about the past. This amateur production of history sits at the boundary between object and narrative. It also occupies a border between the art of cultivating the memory to store ideas in the “rooms” of the mind’s metaphorical “house” and the empirical, evidence-based social science of history. Writing annals and collecting relics also draws nineteenth-century history together with the contemporary “fancy” material style that used surprise, variety, color, and striking ornamentation to engage the emotions and the imagination with physical objects.

The Art and Science of Collecting

Watson’s relic box transforms the classical art of training the memory to function like a house with rooms for storing ideas into a physical box with compartments for holding evidence. During his brief stint as a Philadelphia bookseller before becoming cashier of the Bank of Germantown in 1814, Watson joined with the Baltimore publisher Edward J. Coale to publish a memory manual Mnemonika; or, Chronological Tablets (1812). According to the preface, “some are so fortunate by nature, that their minds may be compared to a miser’s chest, from which nothing is ever lost. Others must rely upon art for that which nature has denied.” Mnemonika is a list of “remarkable occurrences” rather than a program for training the mind, but it presumes that readers already understand their memories architecturally as houses or as chests with compartments. In his box, Watson turned this art of cultivating a mental miser’s chest into a physical artwork of wood, brass, and relic materials. But in keeping with his interest in the curiosity of ordinary local life, Watson did not order an ersatz medieval coffer for his collection. Instead, the form of a rectangular body perched on small feet evoked other common household objects like a Pennsylvania spice box—a receptacle for valuables—and sewing and jewelry boxes. Although the box turned “remarkable” relic wood into an artful shape, that form was still, like the histories Watson would collect in it, the ordinary work of everyday people.

Watson’s collecting and publishing also drew on the scientific methods of natural history. His relic box was not a purely personal affair but was oriented, through both his labels and his collecting practices, towards an outside audience. Watson documented the significance of nearly all of the objects in the box—including the wood of the box itself—by attaching paper labels. In addition to demonstrating the rational for each item’s inclusion, the labels also reveal a network of collectors. For example, the “handle of Wm Penn’s Bookcase” was first acquired by a Peter Worrel who gave it to Ge[orge] Dillwyn who gave it to H. Coleman who, finally, gave it to Watson. Relic collecting required more than making private, sentimental connections to objects. Devotees integrated themselves into a larger social web much like the networks that connected colonial and metropolitan naturalists. Watson also drew other members of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which he helped to found, into his efforts to document the past using local informants. Like the natural historians who obtained specimens from indigenous people and slaves, Watson and other Historical Society members systematically collected oral histories from elderly persons, including African Americans and Native Americans, for the Annals. In many ways, therefore, the relic box and Watson’s writings represent early forays into archaeology and social history, which both use empirical methods derived from the collecting practices of natural historians.

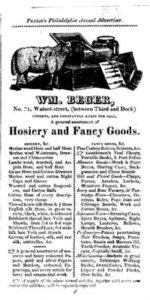

By blending art and science into a physical object, Watson’s relic box ultimately connects history to the “fancy” style of many other contemporary material objects that also sought to engage both the intellect and the senses. “Fancy goods,” as demonstrated by the inventory in this Philadelphia merchant’s advertisement, consisted of games, “surprising” sword canes or telescopes, and small, personal objects like scissors, shaving cases, lockets, hair brushes, soaps, and liquor flasks (fig. 3). Like the relics in Watson’s box, some of these objects are delicate and require careful handling, others are linked to women’s private lives, and still others are ornamental containers for valuable possessions like the relic box itself. Overall, according to decorative arts expert Sumpter Priddy, the fancy material style aimed to elicit a “wide range of emotional responses … delight, awe, surprise, and laughter. These were triggered not just by the stunning nature of the objects,” Priddy maintains, “but also by the dynamic combination of images and allusions that connected the viewer’s imagination to the larger world.” Watson sought to imbue history with the sensational and sensual qualities of this fancy style. “If we would make the incidents of olden time familiar and popular by seizing on the affections and stirring the feelings of modern generations,” Watson explained in his Historic Tales of Olden Time (1832), “we must first delight them with the comic and the strange of history and afterwards win them to graver researches.” Watson’s historiographical contribution was that serious historical narratives could wait.

Labeling the Past

With the exception of the “knitting bag and sheaf,” which has been recognized as a rare Renaissance sweet bag and knife sheath, the objects in Watson’s box are neither striking examples of American design nor valuable artifacts. But the labels change these objects of daily use to fodder for the imagination and to sources of fancy and delight: wood from Penn’s Treaty Elm, Colonel Alex Fanning’s snuff box, sand from the Sahara. With these associations, Watson made the ordinary, material world testify to the strangeness of its experiences in the same way that the vernacular, fancy style used eye-popping colors, Japanned patterns, perfumes, trompe l’oeil painting, or amusing slogans to transform objects of everyday use into opportunities for imaginative engagement.

Certainly curiosity cabinets also used labels to show that an otherwise ordinary object had come from far away. However, as historian Lois Dietz notes, Watson’s collection had stricter selection criteria than the typical curiosity cabinet. Virtually all of its objects were important for their relationship to the past and not for their rarity or for their foreign manufacture. As a result, the box creates a distance between past and present because it only preserves objects that have existed in the past. For example, Watson’s labels distinguished the buttons in the box from contemporary buttons because of their age, because of the people they have been attached to, and because of the events they have witnessed (fig. 4). If their existence in the past makes these buttons different from functionally equivalent, modern buttons, then the past must be a foreign place from the present. Conversely, if the past is different from the present, then the objects connected to it become more valuable and more worthy of imaginative engagement.

Watson’s perception of the past as a rarity that had to be labeled and preserved was not shared by all of his contemporaries. According to the diary of his friend and fellow historian Deborah Norris Logan, his wife, Phoebe Crowell Watson, managed to reject at least one elderly tea table that her husband tried to collect and install in their house as a relic. For her, it was junk, not history. Phoebe Watson judged the tea table by its usefulness and probably also by its style. The fact that the table had existed in the past mattered little if it was too rickety to use or if its scruffy appearance made it seem that the Watsons could not afford better furniture. Her reaction reminds us that whether or not women chose to participate in the work of producing history, they could still be performing the work of a curator or preservationist. John Watson’s antiquarian collecting of large and small relics probably added significantly to his wife’s labor. Neither the buttons nor the tea tables were magically protected from disintegration by the action of Watson’s mind.

Someone was paid to build the relic box; Phoebe Watson refused to dust another tea table.

A Picture of Changing Time

The wood that makes up this box represents an unbroken history leading from the first European contact to the creation of the United States. Yet, the overly small and excessively ornamental feet on which this block of wood poses literally and figuratively undercut the stability of this “grave” history. Their paw shape and flowery brackets contrast sharply with the rigid lines and geometrical inlays that compose the box. This union of the inanimate box and the potentially animated feet is grotesque and whimsical rather than sublime. According to the label Watson pasted inside the box, it is primarily constructed of elm wood from Penn’s Treaty Tree, which fell over during a storm in 1810. The walnut border comes from “a cluster of forest trees” that stood before Independence Hall. Watson associates both the walnut and the elm with the Founding Fathers and with the trees that covered the area prior to European arrival. The small “star[s] of mahogany” on the lid and front of the box come from “the house in St. Domingo where Columbus dwelt.” These inlaid woods replicate a triumphal narrative of progress catalyzed by the actions of great white men from Columbus (mahogany) through Penn (elm) to the United States (walnut). Externally, the box tells a story that resembles the “discoveries of countries” and “foundations of empires” listed in Mnemonika. Yet nearly everything else about the box challenges this traditional concept of history.

The relic wood itself generates a tension between the hard work of great men and the desire for leisure in a pastoral “cluster of forest trees.” Typically, the pastoral ideal offers escape from urbanization, mechanization, and linear time, but Watson did not simply use history to flee Jacksonian America. While some of his contemporaries longed to escape back into the slower life of an idealized past, Watson enjoyed experiencing the different tempos of modernity and history, and he was especially delighted by sudden shifts in time. He could suddenly arrest time by holding a miniature relic or speed it up by riding on one of the new forms of steam-powered transportation. For example, his account of a train ride in 1835 abounds with excitement rather than anti-technological nostalgia. “When we had attached ourselves to the Locomotive Engine,” Watson recounted, “Oh! With what rapidity we went! It was an amusement to try to count the panels of the fences as we passed them. We went faster—(15 m an hour) than I could count them beyond 20 to 30 times! Wonderful invention!” Even after the event, Watson’s exclamation points and interjections convey a very unantiquarian enthusiasm for speed. A similar delight in manipulating the pace of time appears in the contrast between the lively little feet and the measured procession of history in the wood of the box. The objects in the box also document sudden change: dresses less than fifty years old are already in rags; coffins buried in the last century are dug up to make way for new water pipes; steamboats are dashed to pieces by waterfalls; cities are burned to the ground. These miniature relics, like the fence posts Watson tries to count from the train, allow the eye and the hand to stop time for a moment in contemplation, but their ruined state also makes the viewer aware that time is passing rapidly.

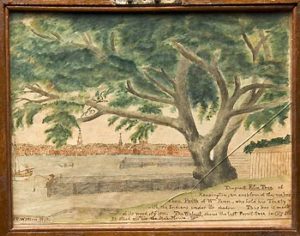

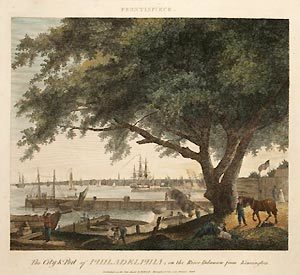

Different tempos juxtaposed against one another also form the subject of the watercolor inside the box (fig. 5). Watson’s adaptation of William Birch’s frontispiece to The City of Philadelphia … as It Appeared in the Year 1800 (fig. 6) presents a pastoral world of leisure against the backdrop of bustling, modern-day Philadelphia. Where Birch emphasizes continuous progress between the construction in the foreground and the commerce in the background, Watson creates a stark difference between pastoral stillness and urban activity. In the left foreground of Birch’s image, two men industriously chop and saw wood for the boat being constructed directly behind them. In the middle ground, another group of builders heat construction materials over a smoky wood fire. The proximity of axes, sawyers, wooden ships, and fire to the elm highlights its vulnerability to destruction in the name of progress. Already this tree is one of the only remaining trees from the forests that once covered this area. At any minute one of the men could look up from his work and see the tree in terms of board feet of lumber. Birch does not necessarily condemn this impulse. His frontispiece reminds Philadelphians of their founding story in which Penn signed a fair and friendly treaty with the Native peoples for the land on which he built their city. If this land can be converted from indigenous to European and from woods to city without struggle or loss, then there is no reason that the tree cannot be converted from a relic of the forest into a trading ship with equal ease and felicity.

Watson disagreed. In his watercolor, he removed the threatening sawyers, boats, and fire. In place of these, he depicted a solitary fisherman, slightly larger than the scale would dictate, sitting on a dock. This figure, like Rip Van Winkle or the Angler from Washington Irving’s The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, avoids productive labor by engaging in the sport of fishing. In this game, he escapes from crowded cities into the static rural world protected by the box where play replaces construction and destruction. The relic box, this image suggests, is Watson’s “fishing hole.” Here he reels his “keepers,” or keepsakes, up from the depths and applies imagination to them in order to visit places and times that are strange and surprising in comparison to the present. “From such materials,” he explained in the Annals of Philadelphia, “we may hope to make provisions for future works of poetry, painting, and romance. It is the raw material to be elaborated into fancy tales and fancy characters.” By enjoying the delightful surprise of moving back and forth in time, of holding onto a moment and letting it go, Watson believed Americans could shape their identity in “fancy tales and fancy characters” rather than being compelled by unseen forces of change to mindlessly produce and destroy.

Preserved Feeling

While Rip Van Winkle’s playful life in the Catskills offers him an escape from domesticity, Watson’s retreat from the masculine labor of founding countries into playful contemplation of the past relies on the miniaturized domestic space of the box for protection from change and decay. This connection between history as child’s play and the home as a space that encloses emotional relationships and separates women from wage labor helps to explain why Watson’s box most resembles contemporary sewing and jewelry boxes, protective cases that are strongly associated with sentiment and domesticity (fig. 7). The jewelry box in this image has paw-shaped feet very similar to those of Watson’s box. Its gilt, stencil decorations of cornucopias, eagles’ heads, and foliage go much further in exemplifying the exuberant colors and patterns typical of the fancy style. Like Watson’s box, the jewelry box is labeled. On the back panel, a painted inscription reads, “M. A. Torris. / Oh years have flown since first we met, / And sorrows have been mine. / I’ve felt when to thy bosom pressed, / That greater bliss was mine. / New York January 1st 1829.” These conventional verses indicate that this box is almost certainly a New Year’s gift marking either a friendship or a romantic relationship. Watson’s relic box takes this idea of making an ornamental box symbolize a private, emotional relationship with a contemporary and turns it into a medium for cementing and protecting a relationship with dead forefathers and dead ways of daily life. The similarity between Watson’s box and this contemporary jewelry box appropriates sentimental domesticity for the work of preservation. The relics of the past can be protected and preserved—”to thy bosom pressed”—to create emotional ties that transcend time and space just as the jewelry box symbolically encloses and preserves the feeling between giver and receiver. But relics, relic boxes, and jewelry boxes are also objects that can be bought and sold. The feelings that they represent are, to some extent, the result of having these new kinds of fancy goods to exchange in order to consume preserved feelings.

Homespun Rural Self-Sufficiency

Inside his box, Watson seems ambivalent about consumer goods. His collection includes several scraps of American silk made by Susanna Wright and Mrs. Haines and her daughters (fig. 8). These fabrics seem to idealize women engaging in pastoral and domestic labors like spinning and weaving. In one sense, therefore, they exemplify the nostalgia for an “age of homespun” that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich describes as an idealized past where women clothed their families without complicated machinery and without leaving the domestic sphere to shop or work. But Watson’s brief history of silk culture in his Annals tells a more complicated story of communal self-sufficiency. In addition to the work of the Wright and Haines families, he describes how the American Philosophical Society and the Pennsylvania Assembly supported the construction of a “public filature at Philadelphia for winding cocoons” in 1770. After a hiatus caused by lack of government support, Watson claims that the same idea of communal self-sufficiency in silk reemerged in the 1830s. “A Holland family on the Frankford road is making it [silk culture] their exclusive business on a large scale; and in Connecticut whole communities are pursuing it, and supplying the public with sewing silk.” Watson’s silk scraps, therefore, also signify a desire for government-supported and scientifically managed rural labor. This kind of work can be carried out in the pastoral space of the farm or of the village so that these communities can become self-sufficient rather than sending men and women to labor for wages and to consume manufactured goods in the city. The “age of homespun” in Watson’s box, therefore, is as much about sustaining an idealized, pastoral lifestyle through cottage industries and scientific farming as it is about celebrating women who model thrift and hard work within the home.

An Appetite for History

The early nineteenth-century invention of the past in “fancy stories and fancy characters” extended well beyond Watson’s relic box or his Annals. For example, Samuel Goodrich, writing as Peter Parley, and Francis Lister Hawks, writing as Lambert Lilly, churned out thousands of anecdote-based history books for children in the 1820s and 1830s. Their fancy histories tolerated poorly documented stories about the adventures of Peter Parley and other characters in order to bring readers imaginatively into tactile contact with the past. This method responded to changing concepts of memory itself from an art to a biological organ. In his preface to The History of New England, Illustrated by Tales, Sketches, Anecdotes, and Adventures (1831), Lilly explains children’s minds as though they were stomachs. “The first impulse of a child,” he says somewhat contemptuously, “is to feed his imagination, and satiate his curiosity.” Although he knows that children’s appetites are unsound, Lilly writes his history according to the laws of human development. “Children are impelled by their feelings and tastes, and we cannot change their nature. The only way to guide them safely through the first giddy paths of their existence, is to consult their nature, and conform to their dispositions.” The History of New England assumes children are developmentally incapable of understanding better-researched narratives and provides them with colorful, apocryphal stories instead. Lilly’s idea that physical appetites govern the mind indicates that fancy, anecdotal history increasingly functions as a concession to memory that has become a physical organ.

Watson’s shift from memory as a metaphorical miser’s chest to memory as an appetite appears most clearly when he has his head examined by phrenologist A. D. Ditmars in 1835. The word “memory” does not appear in Watson’s transcript of the phrenologist’s report. Instead, Ditmars uses Watson’s head shape to determine that his capacity for remembering has changed from a strong ability to remember faces and places to an ability to remember historic facts and dates. Watson’s memory changes over time, just as a child’s memory gradually matures. But the memory still remains fixed by the growth and decay of the physical structure of the head. Ditmars does not suggest that any amount of art or cultivation will allow Watson to regain his memory of faces and names.

Watson’s interest in the past, according to this reading, comes primarily through his “organ of Self Respect.” This organ is “very high indeed … Should like to command & to rule—would have been military, but that my organ of destructiveness was not large—don’t like to see pain & misery inflicted.” He concludes, “Self Respect & veneration & comparison being very high & full, are the cause of my love of Relics, and my Acquisitiveness makes me gather & keep that which is rare & curious.” It seems fairly obvious why Watson links the organs of veneration, comparative reasoning, and acquisitiveness to his collecting activities. Interest in the past requires an emotional respect for its significance and delight in the difference between past and present. The miserly organ of acquisitiveness naturalizes the desire to snatch and hold onto things that Watson and Coale had once perceived as only a metaphor in Mnemonika. “Self Respect,” in contrast, does not appear like an obvious quality for a relic collector. As Watson explains it, however, it demonstrates the strengths and weaknesses of fancy history’s effort to blend art and empiricism to produce a past that people will want to protect.

According to Ditmars’s phrenological reading, Watson naturally desires to “command and rule” and is just as naturally unable to destroy anything. Thanks to his insufficient “organ of destructiveness,” Watson is incapable of throwing out the Indian hemp or the woman’s shoe buckle or the “piece of coffin!” because they feed this appetite for delight even though they do not add up to a single, coherent narrative of the past. However, Watson does not acknowledge, as Mease does, that a sense of entitlement to history travels along with the humane desire to preserve it. The complicated politics of rendering, say, indigenous objects or other people’s coffins as history are entirely absent from Watson’s “fancy tales.” Instead, all his evidence demonstrates the size of his self-respect. The fact that this organ is large shows, in turn, that he is entitled to collect this evidence. Watson’s relics reveal the strength of his appetites and his physical capacity to command and rule. But because the objects that he acquires are evidence of his physical nature, they cannot critique his physical desires. By positing a natural drive to feed the imagination on relics and anecdotes, Watson and other creators of “fancy tales and fancy characters” fail to remember that history is an art as well as a science and that, like all human-fabricated things, destruction is its genesis and its destiny.

Further Reading:

Out of the numerous studies of collecting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, my evaluation of Watson’s relic box especially benefitted from David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge, 1985); Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006); Judith Pascoe, The Hummingbird Cabinet: A Rare and Curious History of Romantic Collectors (Ithaca, N.Y., 2006); Susan Stabile, Memory’s Daughters: The Material Culture of Remembrance in Eighteenth-Century America (Ithaca, N.Y., 2004); Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, N.C., 1993); and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York, 2001).

For vernacular material culture in the early nineteenth century, I used Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790-1840 (Milwaukee, 2004) as well as the collections in the Winterthur Museum. I am very grateful to the Winterthur Museum and Library for a fellowship, which allowed me extensive access to their collections, and to staff members Linda Eaton, Sara Jatcko, Helena Richardson, and Jeanne Solensky for pointing out Watson to me and for sharing their insights on boxes and ruins.

The most detailed study of John Fanning Watson is Deborah Dependahl Waters, “Philadelphia’s Boswell: John Fanning Watson,” PMHB 98 (January 1974): 3-52. The only analysis of the relic box that I am aware of is by Lois Amorette Dietz, “John Fanning Watson: Looking Ahead With a Backwards Glance” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2004). Watson’s unpublished manuscripts, journals, and letters are rich archives for understanding how nineteenth-century Americans produced history. They are divided between the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts at the Winterthur Library and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. I am grateful to both the Winterthur Library and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania for permission to publish the quotations from Watson’s manuscripts.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.1 (October, 2009).

Yvette Piggush is an assistant professor of English at Florida International University. She is working on a book manuscript titled We Have No Ruins: The Culture of Historical Consciousness in the Early United States, 1790-1840.