Fiction for the Purposes of History

Abe is a novel based on the early life of Abraham Lincoln. It draws deeply on historical scholarship, but it is not a biography. Rather, it is an imaginative recreation of life as a young Abe Lincoln might have lived it, and of the people, scenes, and influences that helped produce his character. When an historian writes a book of this kind, the reader has a right to ask why he has chosen to write fiction instead of history? And what sort of truth-value can we expect of a novelistic representation of the past?

Anyone who has worked with historical records knows that the documentation of any large, complex, or significant human event is never fully adequate or reliable. And when one attempts to account for the motives and beliefs that govern human action, information becomes even more slippery and complex. It follows that historians often know more about the stories they tell than can be proved according to the rules of the discipline. There comes a moment, therefore, when the historian must choose between telling the whole story as he or she has come to know it, or only what can be proved with evidence and argument. If you prefer the realization of the story to the perfection of the argument, what you are writing is historical fiction, not “history.” And to keep faith with the reader, you are obliged to identify it as such.

The argument most frequently made on behalf of historical fiction is that, if it is responsibly done, it can be an effective instrument of popular education, or at least a means for stimulating interest in the study of history. Most practicing historians I know were first attracted to their subjects by reading historical fiction. But I’d like to offer a stronger argument: if properly understood, the writing of historical fiction can be a valuable adjunct to the work of historians in their discipline. Historical fiction may do as well as history for telling what happened, when, and how. It can, and should, be based on the same kind of research and rigorous analysis of evidence. But the distinction and advantage of the fictional form lies in the way it uses evidence and represents conclusions.

All historical interpretation rests on hypotheses about the way things, people, and institutions work. The historian develops hypotheses analytically; the novelist may (I would say should) undertake the same kind of analysis, but the final product is synthetic rather than analytical. The historian’s authority with the reader is gained through his/her open display of the whole architecture of evidence-gathering and interpretation.

The novelist’s authority with the reader is gained by other means: the ability to give a plausible account of human motives and actions, to evoke a believable sense of the life and culture of a past time. This depends not only on accuracy of research, but on the consistency and completeness with which a novel develops its essential premises about the character and his or her world–so that what happens in the story seems necessary and appropriate, not arbitrary or anachronistic or forced. To achieve that kind of plausibility, the novelist has to alter and rearrange the facts: change the order of actual events, invent characters and happenings, supply from imagination the information missing from the record. If there is truth in this kind of representation, it is poetic rather than historiographical: it sacrifices fidelity to nonessential facts in order to create in the reader a vivid sense of what the facts mean.

If this method has its flaws as a guide to fact, it also provides a needed corrective to some of the occupational biases of historiography. History writing is governed by hindsight. But history, as experienced, is always indeterminate: historical actors cannot know what will happen next, let alone what significance events will have. The novelist has to imagine history from the inside, to understand the different subjectivities that shaped individual understandings of events, to set aside historical hindsight and appreciate the indeterminate nature of history as it is lived.

The novelist’s representation of history is less like a mirror held up to reality than it is a simulacrum or model of the historical world, miniaturized and compressed in scale and time. The making of such a model demands that the historian make historical hypotheses literal and concrete; it demands that the writer treat what he or she believes to be true as if it was certainly true, so true that a world could be constructed based upon those ideas that would seem credibly to work. Is it your theory that historical action is driven by abstract impersonal forces? or individual calculations of rational self-interest? or oedipal rage? or the play of significations? Then portray for me a human life, in which I can believe, that is lived in these terms. Through this process a kind of truth is, if not discovered, then at least tested,by a kind of thought-experiment.

As a scholar I’ve been concerned with the ways in which communities and nations transform their historical experience into the symbolic terms of myth, and then use mythological renderings of the past to organize their thinking about their values, their place in the world, their responses to crises, their projects for the future. My work has been part of that broad and complex movement toward acritical or revisionist historiography, which has shaped our profession since “the Sixties”–a movement whose project has been to demystify the governing ideologies of the nation (and the profession), and to recover the historical experience and consciousness of peoples and classes previously excluded from the history written by the “victors.” But though the classic models of historical fiction typically celebrate “victors’ history,” there is no reason why fiction cannot become a vehicle for critical historiography. The work of social historians in recovering the experience of hitherto “invisible classes” provides the novelist with a firm basis for imagining their lives. And precisely because the novelist recovers the indeterminacy of a past time, he or she is not bound simply to celebrate the mere outcome, but is free to explore those alternative possibilities for belief, action, and political change, unrealized by history, which existed in the past. In so doing, the novelist may restore, as imaginable possibilities, the ideas, movements, and values defeated or discarded in the struggles that produced the modern state–may produce a counter-myth, to offset the victors’ mythology of the traditional historical romance.

As a scholar, you engage the myths of your society analytically–holding them at a distance. As a fiction writer, you meet those myths on their own ground–the mental space in which memories, traditions, and dreams interact–and you address them in their own language of evocative symbolism. If you succeed, you may contribute directly to the mythology and the public culture that you have merely studied before. Perhaps you can even change that culture in positive ways.

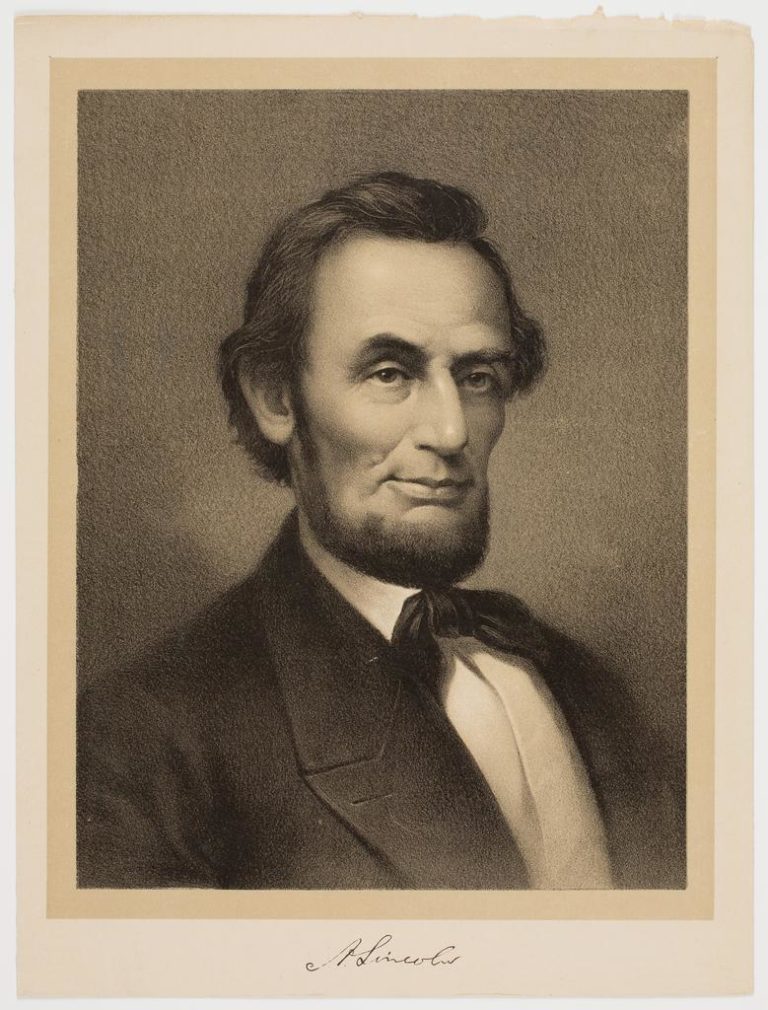

I chose to write fiction about Abraham Lincoln because he is a mythic figure in American culture, because the controversies of which he was the center remain central to our national life more than a hundred years after his death, and because, for all that has been written about him, he remains a figure full of imaginative potential, symbolizing possibilities deeply yearned for but still unrealized by American history. If he had not been killed, could he–would he–have made a difference in the bitter history of racial oppression that followed the failure of Reconstruction?

The answer to that question rests, in large part, on one’s reading of his character and motives. Historians and biographers tell us what the completed man was like, what his mature ideas were, and give us an idea of the contradictory elements of his character. What I wanted to do was to imagine how he got to be that man. He was raised in poverty, and had almost no formal education. Where did the ambition and intellectual brilliance come from? What was the basis and nature of his famous compassion? What hatreds and resentments did he have to overcome to achieve it? Where did the iron come from that allowed him to hold his course through the horror of the Civil War? How did he experience, and what did he make of, the racial conflict that was at the bottom of his, and his nation’s, trial? Only in fiction does the historical writer have the freedom to fully imagine and represent for the reader the inner life of his or her subject–which can never be adequately documented.

Most incidents in the novel take off from real (or at least attested) events, although I made minor alterations in sequence and chronology, and converted some indirect or “reading” relationships with historical figures into face-to-face encounters. The guiding principle behind such inventions was always to dramatize the play of persons, ideas, and forces that shaped Lincoln’s character as I understand it. Although I would not want the novel read as factual history, I would be willing to defend my interpretation of Lincoln’s character on scholarly grounds.

Given the elements that entered into the making of his character (and our culture), Lincoln might have become a greater and more complete emancipator than he actually was. There are in his writings, there were in the society that reared him, ideas and inclinations that looked through the endemic racism of the time toward a genuine understanding of equality, justice, and democracy. There were also elements in his character, and in his culture, of racial antipathy, violence, and power seeking that might have made him a great deal worse than he turned out to be. By engaging with the Lincoln myth as a novelist, I hope to restore for the reader some sense of the rich potential of Lincoln’s character, and by analogy to enrich his/her understanding of the latent potentials of American history and culture.

This article originally appeared in issue 1.1 (September, 2000).

Common-Place asks scholar-writer Richard Slotkin, author of such classics of American cultural history as Regeneration Through Violence, The Fatal Environment, Gunfighter Nation, and, most recently, of Abe: A Novel of the Young Lincoln: “What can you do as a novelist that you can’t as an historian–and vice versa?