Finding a Black Founder

“My brother restored Bethel Church and would love to tell you about it,” the man at the teashop said. “Did you know that he cleaned George Washington’s chimney,” two researchers at the National Parks Service told me. “He had some country property,” a distinguished historian said while we were working on another project.

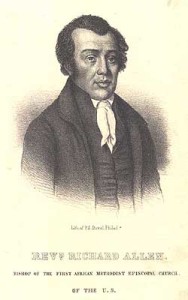

Writing African American biography was supposed to be an exercise in scholarly ingenuity, if not futility. There simply are not enough records of early black leaders—much less non-elites—to detail colonial or Revolutionary-era African American lives in the definitive way that, say, David McCulloch could of John Adams. And so, before even writing a single word of my forthcoming biography of African American hero Richard Allen, a former slave, fabled black activist, and founder of Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia, I had my mantras ready: “perhaps he did this”; “the record fails to shed light on that”; “he may indeed have been there but we do not know.” Allen, who lived from 1760 to 1831, remains one of the best-known black leaders of the early republic, and he certainly left more than enough records for any would-be biographer. He penned pamphlets of protest, left his mark on Philadelphia’s most significant free black institutions, and produced a moving spiritual autobiography. Yet considerable roadblocks remained. “Where are Richard Allen’s papers,” people routinely ask? “There aren’t any,” I reply. Allen left no daily journal, no private correspondence, no family papers for scholars to mine. Indeed, even his autobiography has limitations. Not only did it end in 1816, with Bethel Church’s full independence from white Methodists, but it failed to discuss such key political themes as Allen’s initial interest in Paul Cuffee-style African colonization.

Thus when I undertook Black Founder: Richard Allen, African Americans and the Early Republic a few years ago, I planned to write a life-and-times book, filling any empty space about Allen’s personal life or political activism with copious references to new scholarly work about things going on around him: community building efforts in the emancipating North, the rise of black pamphleteers, the emergence of African American leaders. Allen would fade in and out of focus as the paper trail went dry.

Thankfully, Allen proved me wrong. While he did not leave a voluminous paper trail, his incessant involvement in public and black community-building activities continues to provide details about his life and thought as perhaps the preeminent black leader of the early republic. Rather than too few sources, I soon found myself facing a mounting pile of evidence. On issue after issue, it seemed, there was an “Allen effect” pulling me to sources. The task has become not finding bits and pieces of evidence about Allen’s life but what to make of them.

One neat example of the Allen effect occurred earlier this year when I tried to uncover the intellectual roots of Allen’s first pamphlet, “A Narrative . . . of the Black People,” known off-handedly as the yellow fever pamphlet. Published in 1794 and co-authored with Absalom Jones, the pamphlet publicly rebuked the printer Matthew Carey for his racist depictions of African American activity during Philadelphia’s famous yellow fever epidemic. Carey claimed that many blacks had exploited the sickness to pilfer white homes; Allen and Jones parried the assertion by claiming that blacks had nobly served ailing white citizens. The document became the first copyrighted work by black authors in the United States. But because we have no manuscript original, or letters about the writing of it, there is no way to know definitively what sources Allen and Jones used. Phil Lapsansky, an archivist at the Library Company of Philadelphia, opened the door on this issue by giving me Absalom Jones’s will, which showed that Jones had a copy of the works of Josephus. An ancient Jewish scholar, Flavius Josephus had joined a rebellion against Roman authorities only to betray his fellow conspirators. Josephus subsequently became an important scholar in and about the Roman republic. A traitor and scoundrel to some, others viewed Josephus as an oracle—a man who captured the struggles of the Jewish people as few writers ever had. Some early commentators even believed that God had saved Josephus precisely so that he could relay the history of oppressed Jews. As the modern introduction to Josephus: The Complete Works notes, Josephus aimed at nothing less than the “exaltation the Jewish people in the eyes of the Greco-Roman world.”

Hmmm, I wondered, that sounded very much like Allen and Jones’s goal in the yellow fever pamphlet. Did Allen himself own this book? Sure enough he did. But did Allen and Jones have copies of Josephus when they wrote their famous document? “I’d double check that,” said Library Company librarian Jim Green, sounding doubtful. The Library Company had a beautiful 1795 edition, showing that Allen and Jones had indeed subscribed for a copy of Josephus and were probably familiar with it before securing the book! Allen and Jones, it appeared, had used Josephus as a model for writing history from the viewpoint of an oppressed but chosen people.

Another example of the Allen effect: I recently went back to Bethel Church to reexamine some records from the end of Allen’s life. Rather than go directly into the archives this time, I decided to hang out on “Richard Allen Avenue” at Sixth and Lombard and soak up the atmosphere. As tour buses passed by declaring Bethel a key stop on the Underground Railroad, I became part of two revealing exchanges about the place of Allen’s church in the lives of black and white Philadelphians of a certain age. First, a white woman who appeared to be in her mid-fifties passed by and, noticing my camera and consuming interest in Bethel, said that “white people aren’t allowed in there. Ever heard of Crow Jim?” Reverse discrimination at Bethel? No way. About ten minutes later, an African American man—a house painter, to judge by his splattered overalls—about the same age passed by on the other side of the church. Without breaking stride, he said, “That’s a beautiful church, isn’t it.” Two contemporary perspectives on Bethel Church, both from people of the civil-rights generation, and two perspectives that also provided historical insight. Even into the twentieth century, I learned, Bethel’s Independence struck a nerve for some in the white community, while in the black community it remained a fiercely prideful monument of black uplift.

Property deeds inside the church enhanced my appreciation of what Allen was trying to do at Bethel. On the one hand, these deeds from the 1790s and early 1800s told the tale of Richard Allen’s rapid economic ascension in bustling early national Philadelphia. As he bought property after property, Allen listed himself in a succession of new occupations, from dealer to master chimney sweep to African minister. In this sense, Allen became a relatively well-known man about town, a black man who not only inaugurated an African church but also owned his own home and several rental properties as well. On the other hand, the deeds illuminated Allen’s intense concern with protecting Bethel’s independence during and after his life. Allen’s tale of departing a segregated white church and starting his own congregation roughly a mile away is well known. But Allen was a shrewd and very practical man, and he made sure that he owned not only Bethel property itself but much of the land and rent-bearing dwellings around it. He even purchased a sliver of land, the width of a fence, next to Bethel! No one was going to pull a fast one on Allen and black churchgoers by selling neighboring property to white hecklers or malcontents. That urban morality play I had just witnessed—black pride and independence versus smoldering white resentment—resonated deep in Bethel archives.

The church held even more treasures. Although I had been inside before, I had not met the remarkable woman who still provides weekly tours. Her name is Katherine Dockens and she is a lineal descendant of Richard Allen. “Has anyone ever said that you look like Richard Allen,” I asked. A regal, refined woman, she took the query in stride. “Oh, I get that sometimes.” Mrs. Dockens then guided me through Allen family lore, telling me, for instance, that Allen was remembered as a loving parent. Interestingly, she confided that there were things about Allen that even she did not know. It was with a great sense of pleasure, then, that I sent her a copy of Henry Highland Garnet’s description of meeting “Papa” Allen in the 1820s (so named by young children who would crowd around the great man on his visits to New York), a source generously given to me by John Stauffer of Harvard. “What a wonderful description,” she beamed. I visit Bethel every time I go back to Philadelphia to compare notes with Mrs. Dockens.

The Allen effect marches on. On research visits to Philadelphia, in conversations with colleagues and friends, I have continually encountered juicy tidbits about Allen’s life. “Weird Allen reference,” my girlfriend e-mailed one day, with a note from a Philadelphia physician’s journal about a broadside Allen posted in 1798 asking city residents to release pets left howling in city homes after yet another yellow fever epidemic. (Only a confident person, one growing into a community leader, would post such a note!) And so it goes, with ever-more references offering ever-more insights into, among other things, Allen’s leadership struggles near the end of his life, the socio-economic composition of AME church membership, literacy rates within Bethel church, and on and on. Perhaps this is what all biographers do—chase shreds of paper to the ends of the earth. “I was afraid of this,” my editor said when I explained my most recent Allen find and, well, the latest reason for delaying my manuscript just a few more months. But that so many shreds of paper even exist for Allen is an important testament to a black founder’s enduring presence in early national America.

Further Reading:

See Josephus: The Complete Works (Philadelphia, 1960); Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia” (Philadelphia, 1794), reprinted in Richard Newman, Patrick Rael, Phillip Lapsansky, eds. Pamphlets of Protest: An Anthology of African American Protest Literature, 1790-1860 (Routledge, 2001).

This article originally appeared in issue 5.4 (July, 2005).

Richard S. Newman teaches at the Rochester Institute of Technology and is soon to be finished with his next book, Black Founder: Richard Allen, African Americans and the Early Republic, from NYU Press.