Fine Distinctions

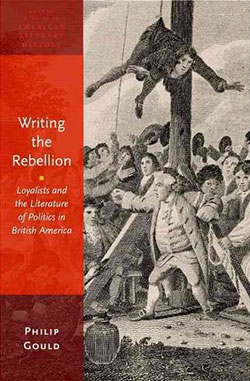

There’s an old military proverb: No army ever rode into battle shouting fine distinctions. In Philip Gould’s Writing the Rebellion, however, the armies fight with pen and printing press, not sword and cannon. In this book, polemical writers shout, sneer, and hiss fine distinctions at each other on a paper battlefield of pamphlets and newspapers, broadsides and burlesques, satires and political theatre. Shades of rhetorical difference occupy every page: sublimity vs. bombast; true vs. false wit; apprehension vs. expression; genius vs. decorum; irony vs. invective; low vs. high burlesque—plus subtle and not-so-subtle contrasts among most of the classic rhetorical strategies and tactics. The subtitle, Loyalists and the Literature of Politics in British America, indicates why disputes about the nuances of literary and stylistic categories predominate in Gould’s analysis. This is a war of words, a contest for the minds and feelings of British subjects in a time of rebellion. It is politics understood as literature, aesthetics understood as politics.

The controlling premise of Writing the Rebellion is that a writerly class of Patriots and Loyalists—each side claiming the title of “civilized English subject” (25)—used disputes over “literary form and aesthetic taste” in order to “leverage political authority” (32). Rebels and Loyalists alike got their political leverage by mocking their opponents as bad writers as well as bad thinkers. As Gould states, “the sometimes tendentious arguments about Parliament’s sovereignty, the common law, and actual and virtual representation segued almost seamlessly into those concerning literary style as a touchstone to political credibility” (32). Furthermore, a “focus on aesthetics assumes that the subject is always already politicized: it functions as the means by which British Americans were reimagining their cultural relations to one another and to Britain itself” (25).

Gould presents case studies in five chapters, each case analyzing in detail a few highly representative Patriot and Loyalist documents, beginning with the Stamp Act crisis of 1765, extending through the meeting of the Continental Congress and the formation of the Continental Association (1774), and concluding with responses to Common Sense (1776) and its various reprintings.

In sequence, the cases dramatize how a considerable percentage of British colonists (estimates range from 20 to 33 percent) at first supposed revolution against England too far-fetched to imagine. Suddenly, it was imaginable. Alarmed, the Loyalists then tried to arrest this momentum of nonsensical imagining, using their writing to restore good sense and calm order. But then the unimaginable kept happening. Rapidly. As events swiftly turned worse, and ultimately punitive, Loyalist lives were daily transformed. “The feelings of divided loyalty usually assigned to them” slipped into devastating feelings of loss, dislocation, isolation—a “dread of no longer being British or American.” Although, Gould observes, we “traditionally have seen the Loyalists as being simply elitist or aloof in their writings, I would argue that such detachment was driven more by the increasing sensations of desperation, outrage, and fear” (168-170).

The first case, on the Stamp Act Crisis, features the Loyalist Martin Howard Jr.’s Letter from a Gentleman at Halifax (1765) versus the answers of two Patriots, Stephen Hopkins (The Rights of Colonies Examined,1764) and James Otis (Vindication of the American Colonies from the Aspersions of the Halifax Gentleman and Brief Remarks on the Defence of the Halifax Libel, both 1765). The stylistic/political issue involves the “sublime” style (Samuel Johnson’s “grand or lofty style”) versus self-indulgent “bombast” and “bathos.” Anticipating the debates a decade ahead, each side claims the grand style for itself and relegates the opposition to one or another level of bathos—drawing fine distinctions, and not gently.

The second case pits Anglican minister Samuel Seabury and his 1774-75 series of pamphlets published under the pen-name “West Chester Farmer” against Alexander Hamilton, who attacked the West Chester Farmer with his own pamphlets, including The Farmer Refuted (1775). Seabury and Hamilton tussled over the proper forms of ridicule: those conveyed by true wit (“ideally modulated, its humor proportioned to the targeted foibles, its premises rooted in sympathy with human nature”) or false wit: self-indulgent, extravagant word-play and punning. With each adversary mocking the other, the shadows of Pope’s Dunciad, “Essay on Criticism,” and “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot” seem to fall on their pages, with Seabury and Hamilton wittily assigning the other a seat among the dunces.

The extensive third case, “Satirizing the Congress: Ancient Balladry and Literary Taste,” makes the Seabury/Hamilton exchange look positively jolly, for Congress gets satirized in “a literature of outrage: verse parodies, mock epistles and public confessions, satiric sketches, false advertisements, cards, cards-in-reply, squibs, closet-dramas, humorous ballads, and comic political fables” (84). The pertinent texts are the anonymous Loyalist burlesque The Association, &c. of the Delegates of the Colonies, at the Grand Congress, Held at Philadelphia, Sept. 1, 1774, Versified, and Adapted to Music (1774) paired with Major John Andre’s take-off on the old ballad “Chevy Chase,” a snarly satire on the American military that he called “The Cow-Chace” (1780). Each exploits the revival of serious interest in ancient ballads that had occurred in Britain around mid-century—a revival Gould treats in considerable detail.

In the widely popular Common Sense, of course, Loyalists encountered their greatest challenge. The fourth case, “Loyalists and the Author of Common Sense,” uses the figure of Thomas Paine to explore the nature of “authorship,” a topic much discussed today in theory circles. Once Paine was revealed as its author (an open secret all along), an increasingly anxious opposition targeted him in person and in persona. For Patriots, Paine qualified as a true “author,” an honorable writer marvelously bringing eloquence to the cause of common sense; for Loyalists, he was unworthy of the name of author, a “scribbling imp,” a “hired Grubb Street hack,” out for the money and unscrupulously promoting the evil schemes and crazy policies of his employers. Yet Loyalists also found Paine useful, for he became a metonymy for the entire cast of rebellious leaders and their propagandists; by extension, if they could skewer him and his reputation, they could wound his sponsors.

The anti-Paine Loyalist works are pamphlets by Maryland’s James Chalmers, Plain Truth andAdditions to Plain Truth (1776), and a pamphlet by Charles Inglis, The True Interest of America Impartially Stated in Certain Strictures on a Pamphlet Intitled Common Sense (1776), plus a series of letters William Smith wrote under the pseudonym “Cato” for Philadelphia newspapers. (Paine answered “Cato” under his own pseudonym, “The Forester.”) The Loyalists disdained Common Sense because Paine rejected monarchy and promoted American independence, but also because of his dangerous philosophy of natural rights and liberties, a wildly idealistic fantasy floating in an imaginary world of flawless people needing no social and political control. “I find no Common Sense in this pamphlet but much uncommon phrenzy,” wrote Inglis (122). In Philadelphia, moreover, the controversy involved rival printers, who, since the conflicts involving Franklin and Zenger, had claimed political neutrality but now faced pressure from both sides to convert their presses into political instruments as opportunities presented themselves to print, reprint, and refute Common Sense.

The fifth case develops a revisionary argument explaining how the Loyalists located Common Sense “New Englandly.” New England, Loyalists insisted, had never been truly English and never truly part of the British Empire. Common Sense is a Puritan text; when New England Puritans trumpet it, they forfeit any claim to “English credentials” (145). In Plain Truth and Additions to Plain Truth, Chalmers even posits Paine as the new Cromwell, thus connecting Loyalist fears of rebellion in 1776 by analogy to the English civil wars of the 1640s. As the Puritans then had nearly destroyed England through regicide, bloody violence, mendacity, and personal ambition (exemplified by Oliver Cromwell), their New England descendants, likewise infected with Puritanism, were now hell-bent on destroying British America.

Writing the Rebellion concludes with an epilogue urging historians to discard their stereotypes about the Loyalists and instead to “account for the seriousness and depth of their political critiques and positions” (172).

In his effort to persuade readers to rethink the literature of the rebellion, Gould faces some rhetorical challenges of his own. Because the specimens are “occasional,” a reader needs information about the particular occasions that sparked the exchange between writers, and it also helps to be familiar with eighteenth-century British literary theories, for they carry over to the colonies. Gould supplies considerable context, but each case necessarily requires an effort to keep in mind the specific historical circumstances serving as the basis for the witticisms, satirical stings, local allusions, etc., of the specimen documents—in short, to get the joke. Although Gould includes sections summarizing the upshot of each case and connecting it with the case to follow, his very close readings do presuppose an attentive reader with some prior knowledge of transatlantic rhetorical practice.

Several projects underlie this brief but dense book. One is surely the recovery of good-but-forgotten Loyalist writers. In this regard, two more maxims come to mind: History is written by the winners and Literature is what gets taught. Accordingly, the national narrative has for generations adopted the major premise that the system of laws, liberties, and values identified as truly American, accompanied by the culture that the United States developed, flows from 1776 and the principles of Independence established by the patriots in their successful conflict with England. Those beliefs likewise form the credo of the United States’ civil religion, and Americans tend to call dissent from them “un-American.” The Loyalists, having lost, are thereby banished to the insignificant margins of American history as we have constructed it. Writing the Rebellion returns them to the discourse.

That developmental narrative has also guided the teaching of American literature—itself a relatively new subject of study that American colleges, until the mid-twentieth-century, taught as a curious but minor departure from The Great Tradition of British Literature from Chaucer to Yesterday. Search the standard classroom anthologies of American literature for any selections from the writers Gould discusses and you will find a great deal of Franklin and Paine but precious little of the Loyalist intellectuals who doubted the wisdom of rebellion from the Mother Country. Gould tries hard, though, especially when it comes to Common Sense. He writes that by “accounting for Loyalist responses to this magnum opus,” he “has aimed to dislodge its traditional place in national history and emphasize instead the literary and political dissent it precipitated” (142).

That’s one heavy rock to move. But maybe he got it to tilt a little. It’s a start.