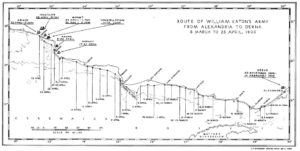

Shortly after the battle, forces loyal to Bashaw Yusuf surrounded Derne and laid siege to Eaton’s army. Yet Eaton was confident that he could easily defeat the besieging forces, march to Tripoli and free the American captives, all in as few as fifteen days. Eaton never had the chance to put his boast to the test, however, for after hearing of the fall of Derne, Yusuf agreed to begin peace negotiations with the United States. A war-weary Jefferson administration consented, and within a few days, Yusuf and the American negotiator in Tripoli agreed on terms: Yusuf agreed to free every American prisoner and to forgo all future attacks on American ships. In exchange, the United States agreed to pay $60,000 to ransom their prisoners, and to withdraw all forces from Tripolitan territory and cease cooperating with Hamet.

On May 19, 1805, the commander of the U.S. fleet sent Eaton a letter ordering him to withdraw all American marines to the U.S. frigate Constellation anchored off Derne, which would evacuate them to Syracuse, Italy. Hamet could leave with the Americans if he chose, but the Arab soldiers and their families were on their own. The terms of peace arranged between the United States and Yusuf ensured no Tripolitan soldiers would attack Americans but made no such promise when it came to the Arabs under Eaton’s command. Eaton briefly refused to comply with the order and begged his superior officer to reconsider, cautioning that if the Americans abandoned the Arabs and their families, “havoc & slaughter will be the inevitable consequence—not a soul of them can escape the savage vengeance of the enemy.” When his superior officer repeated the evacuation order, however, Eaton begrudgingly complied. Hamet saw the writing on the wall and agreed to leave.

Carrying out the evacuation proved challenging. Derne was still besieged by forces loyal to Yusuf, and Eaton feared that a panic would ensue should his Arab allies or the residents of Derne, who had not yet heard of the peace agreement, learn of the coming American retreat. To cover their withdrawal, Eaton lied to the Arabs and to the residents of Derne, telling them the U.S. frigate anchored off the coast was delivering supplies and reinforcements. To further distract his Arab soldiers from the impending evacuation, Eaton ordered them to their posts to prepare for an attack the following morning. Then, under cover of darkness on the night of June 11, 1805, Eaton, Hamet, the marines, and a handful of Hamet’s servants, quietly got into rowboats and headed out towards the USS Constellation, leaving much of their equipment, and every Arab ally behind.

Just as the final rowboat left the shore, the Arab soldiers and residents of Derne realized what had transpired. From his vantage on the ocean, Eaton described the panic that ensued:

. . . the shore, our camp, and the battery were crowded with the distracted soldiery and populace. . . . Some uttering shrieks—some execrations. Finding we were out of reach, they fell upon our tents and horses, which were left standing; carried them off, and prepared themselves for flight. . . . Before break of day our Arabs were all off to the mountains, and with them such of the inhabitants of the town as had means to fly. . . . In a few minutes more we shall lose sight of this devoted city, which has experienced as strange a reverse in so short a time as ever was recorded in the disasters of war; thrown from proud success and elated prospects into an abyss of hopeless wretchedness . . . this moment we drop them from ours into the hands of this enemy for no other crime but too much confidence in us!

Some of Eaton’s former allies scattered into the countryside, desperate to evade the besieging army, while others barricaded themselves inside the city and pledged to fight to the death rather than surrender and face likely execution. As the Constellation sailed away, Eaton lost sight of Derne and its inhabitants; the fate of those left behind remains unknown.

Just as with the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the evacuation from Tripoli generated political controversy in the United States. President Jefferson had hoped the end of hostilities would cause jubilation amongst the American public. But some of the enthusiasm for the war’s end was sapped when news leaked of Eaton’s sudden retreat just as he appeared to be on the verge of victory. Some Americans were also incensed at the terms of the treaty mandating ransom to Tripoli. Federalists, the opposition party to the administration, seized on the ransom payment and the retreat from Derne as a convenient way to condemn Jefferson. In February 1806, a newspaper from coastal Maine, a Federalist stronghold, criticized ransoming the prisoners instead of letting Eaton rescue them: “How much more gratifying to the prisoners, how much more glorious to America it would have been, to have seen the strong arm of yankee bravery, breaking the iron bars . . .” In January 1806, Jefferson defended his actions to Congress in a written address, declaring that he had always envisioned the alliance with Hamet to be limited in scope. “We certainly had never contemplated,” declared Jefferson somewhat facetiously, “nor were we prepared to land an army of our own, or to raise, pay, or subsist an army of Arabs, to march from Derne to Tripoli, and to carry on a land war at such a distance from our resources.” Jefferson blamed Eaton for being too “zealous” and for misconstruing the administration’s intentions to Hamet.