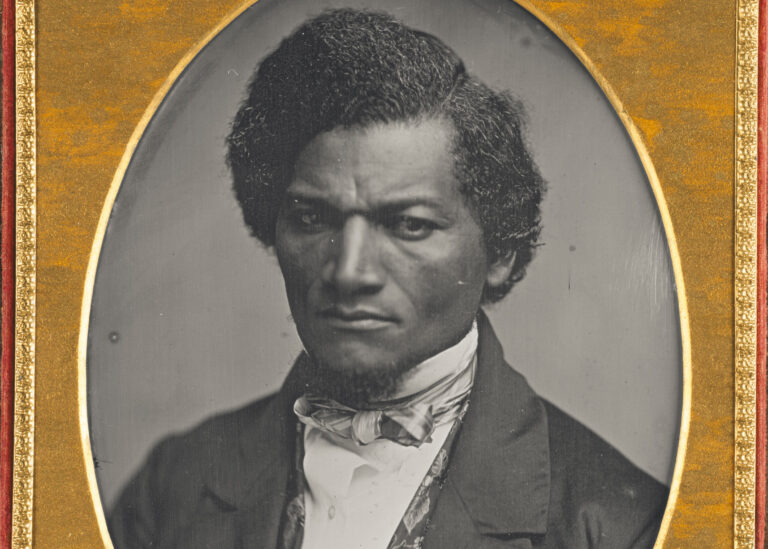

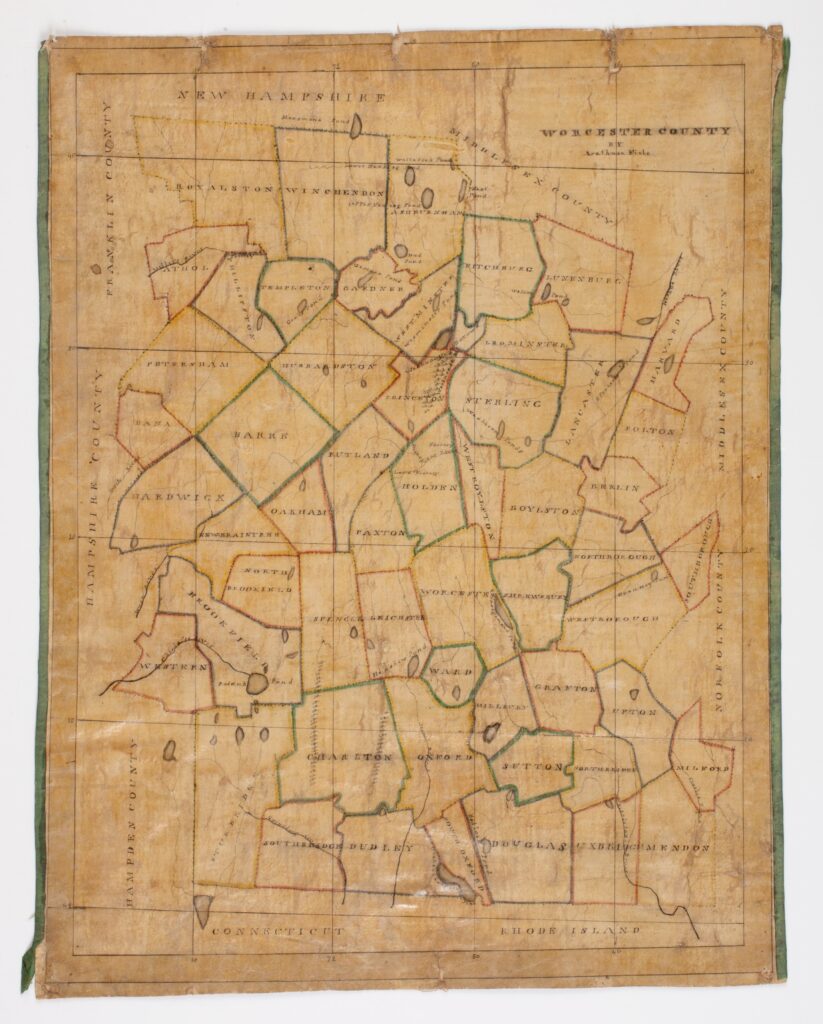

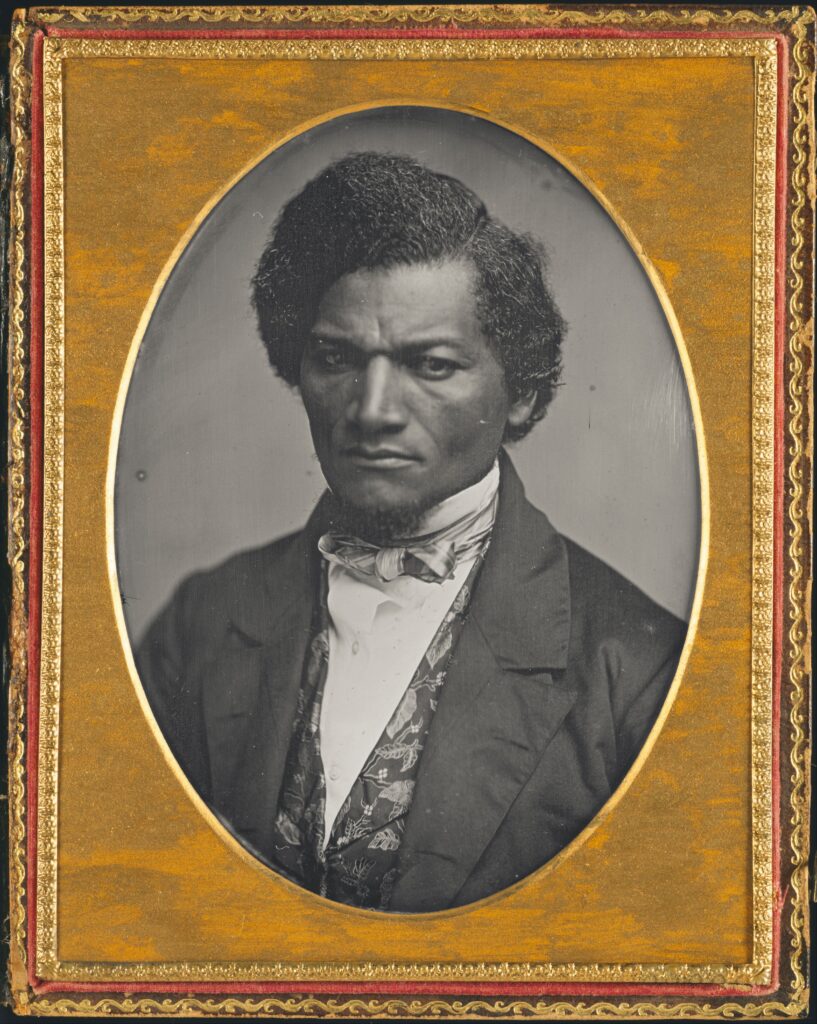

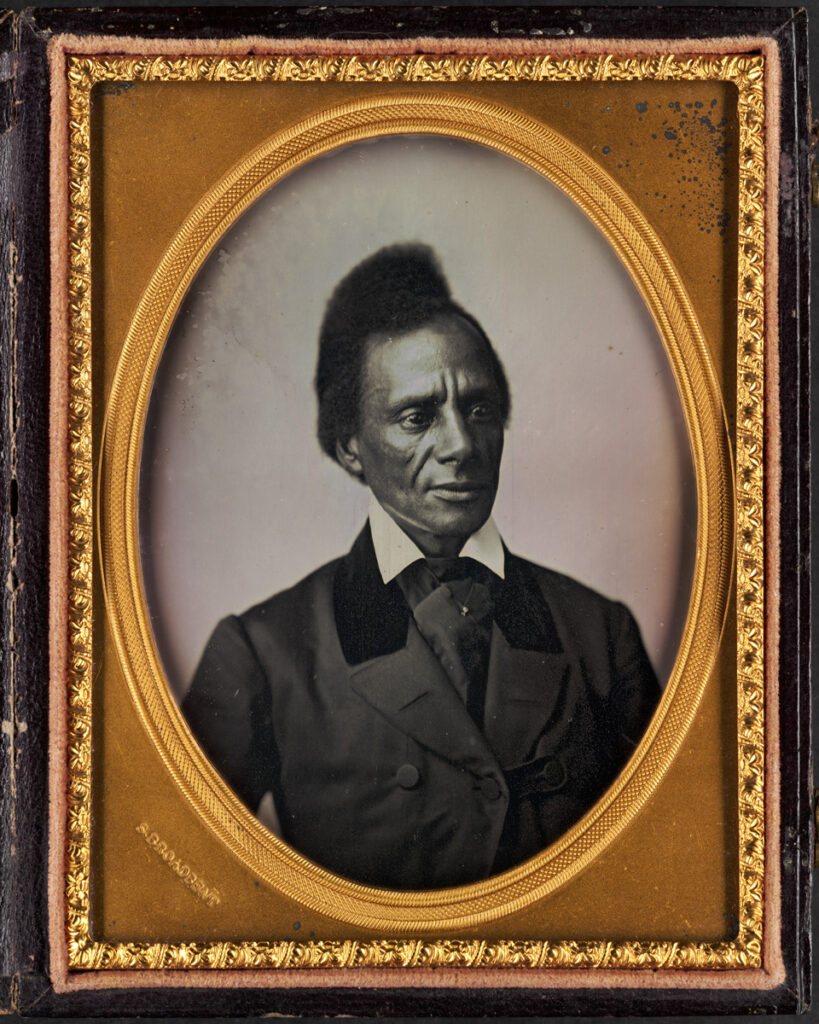

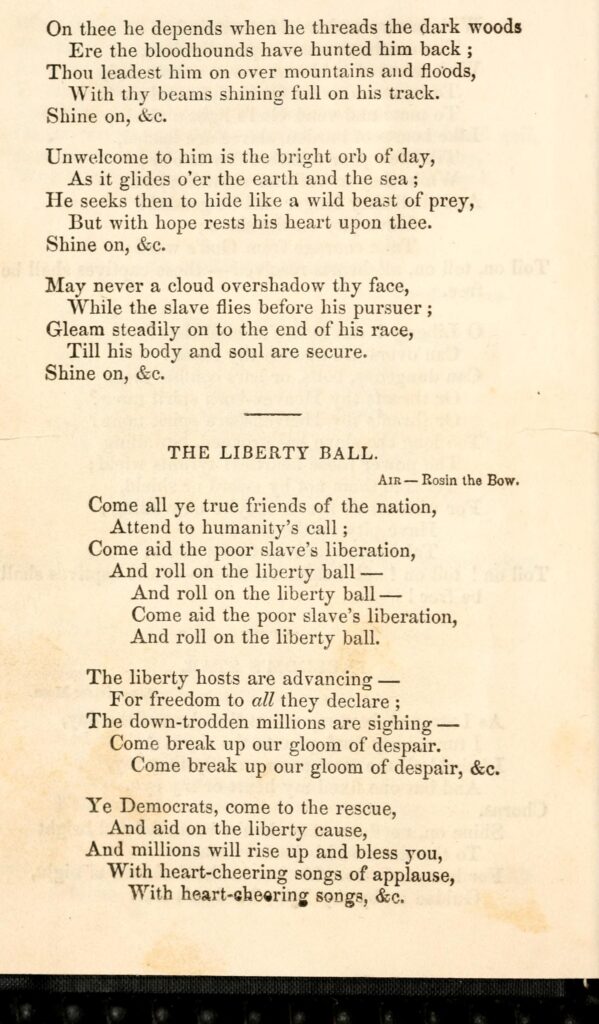

What does Frederick Douglass’s speech to Uxbridge’s “faithful little band of Abolitionists” teach us? The first thing is that Uxbridge, like other rural New England towns, was perhaps naturally inclined toward growing the abolitionist movement once it came because of the region’s cornerstone ideals of independence, morality, and communal nature. Douglass found fertile ground there, as evidenced by both his willingness to visit despite his legal status as a fugitive, and the tangible effect he had on the town. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, despite rural New England being overwhelmingly white, the influence of Black New Englanders—by circumstance like Frederick Douglass and other refugees from slavery, and by birth like Charles Lenox Remond—is clear and should be centered if we are to tell the full story of the contribution of rural New England, and small towns like Uxbridge, to the movement to abolish slavery. A large red sign facing the town square and the preservation of such an important space are good first steps. But the way we remember the stories like these needs further fleshing out if we are to recognize the true meaning and impact of abolition in rural New England.

Further Reading

Secondary Sources

David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018).

Christopher Clark, The Roots of Rural Capitalism: Western Massachusetts, 1780-1860 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990).

Mary Babson Fuhrer, A Crisis of Community: The Trials and Transformation of a New England Town, 1815-1848 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

James and Lois Horton, In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community, and Protest Among Northern Free Blacks, 1700-1860 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Dorothy Sterling, Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Anti-Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1991).

Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

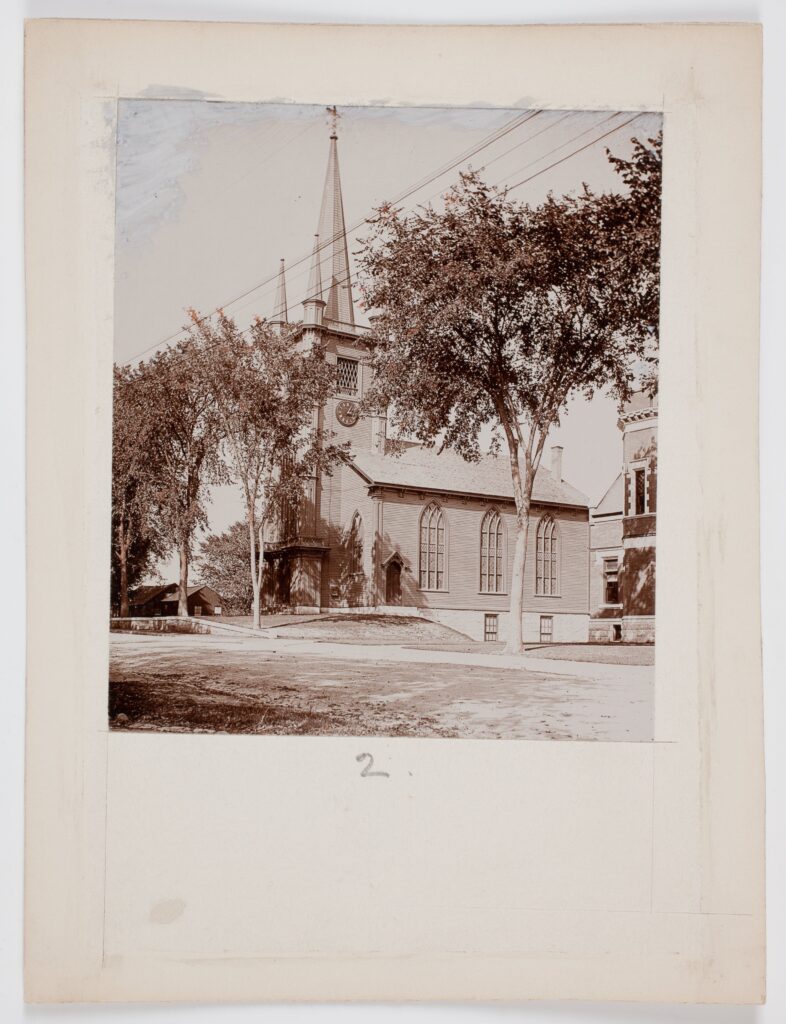

Unitarian Congregation of Uxbridge and Mendon, “Church History from 1668-1994” (https://ucmu.org/history).

Primary Sources

Henry Chapin, Address Delivered at the Unitarian Church, in Uxbridge, Mass., in 1864 (Worcester, MA: Press of Charles Hamilton, 1881).

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself (Boston: Published at the Anti-Slavery Office, 1845).

Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (New York and Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855).

Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself (Boston, MA: De Wolfe & Fiske Co., 1892).

The Emancipator (newspaper).

The Liberator (newspaper).

The Practical Christian (newspaper).

This article originally appeared in June 2023.

C. J. Martin is a research historian at Old Sturbridge Village and teaches at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Emerson College, and the Rhode Island School of Design. His forthcoming book is entitled Our Earnest Remonstrance: Race, Citizenship and Voting Rights in New England, 1770-1843. His research more broadly examines the voices of Black New Englanders in the Early Republic, and the role they and abolitionists played in shaping the politics of the era.