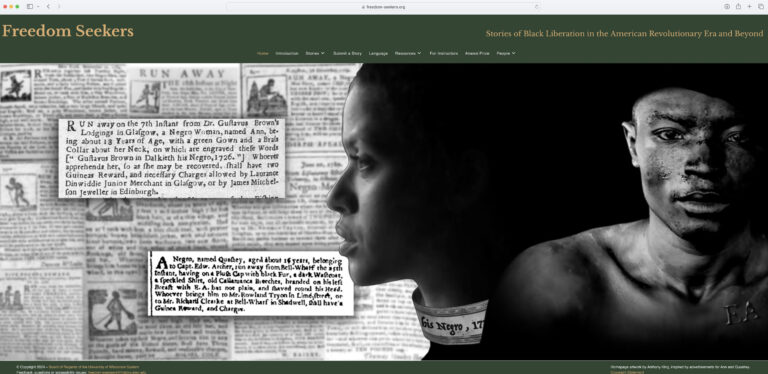

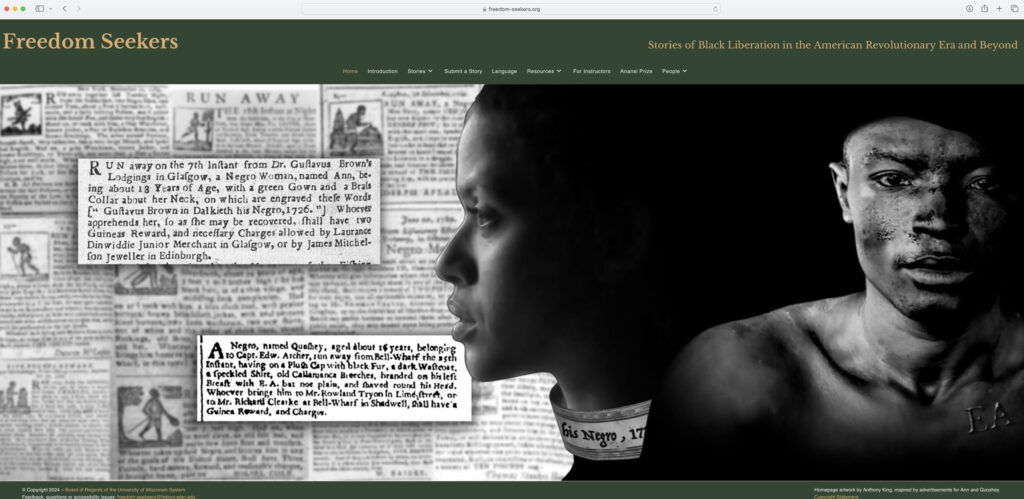

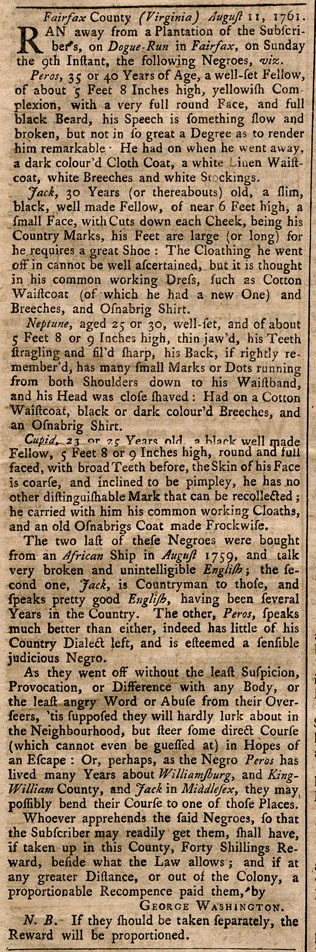

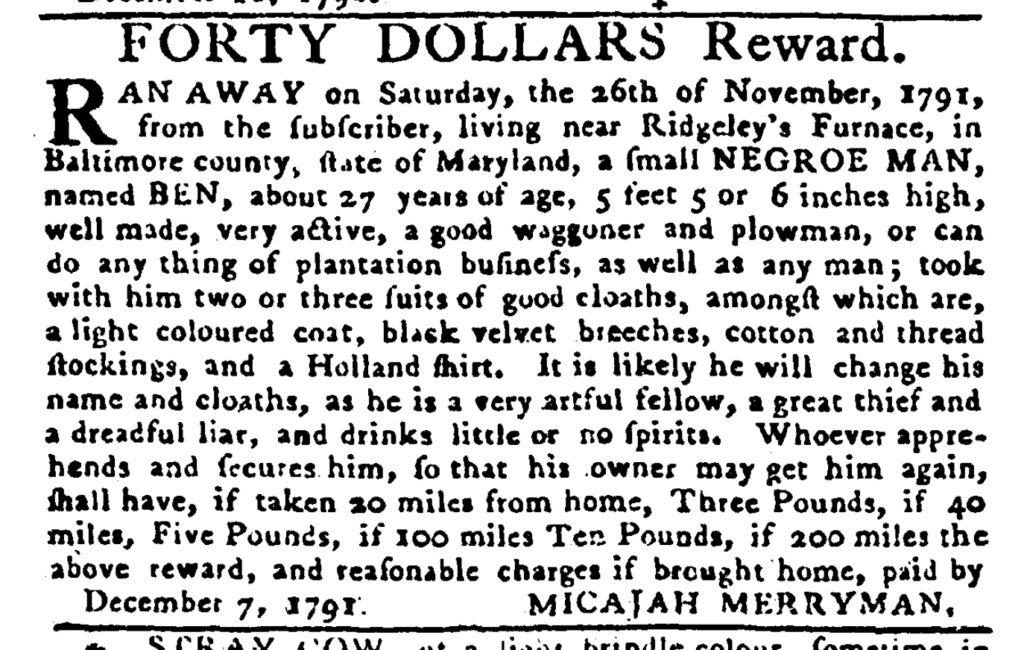

We are living through a time of deep crisis in our nation, and the meaning and significance of freedom and democracy are as controversial today as they were in the late eighteenth century. Our project asks what freedom meant in the eighteenth century, exploring how for many people in North America and across the Atlantic World, liberty meant an end to slavery. Demonstrating their dedication to ideals of liberty at odds with the practices of men such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, tens of thousands of enslaved people absconded, risking their lives to liberate themselves. Their actions were both personal and political as they freed themselves and challenged the system of racial bondage.

It is our hope and expectation that the accumulation of hundreds of freedom seeker stories will provide a new kind of community-built resource, one that will enable us to think about enslaved people who resisted their bondage as individuals rather than as statistics. Freedom Seekers will show how all kinds of men, women, and children who escaped were important actors in the challenge not just to their own enslavement but to slavery more broadly. It will require us to broaden our thinking about the American Revolution to encompass a related but distinct set of bids for freedom and independence.

Further Reading

Karen Cook Bell, Running From Bondage: Enslaved Women and their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Erica Armstrong Dunbar, Never Caught: The Washington’s Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (New York: Atria Books, 2017).

Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007).

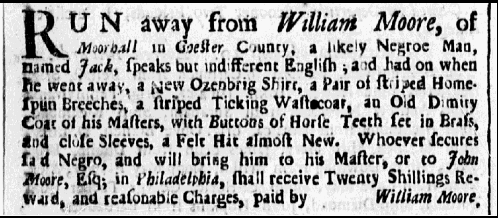

Graham Russell Hodges and Alan Edward Brown, eds., “Pretends to Be Free”: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019; originally published in 1994).

Daniel Meaders, Advertisements for Runaway Slaves in Virginia, 1801-1820 (New York: Garland, 1997).

Simon P. Newman, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Escaped Slaves in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century Jamaica,” William and Mary Quarterly (OI Reader app), June 2018, 1–53. https://oireader.wm.edu/open_wmq/hidden-in-plain-sight/hidden-in-plain-sight-escaped-slaves-in-late-eighteenth-and-early-nineteenth-century-jamaica/ [accessed September 9, 2024].

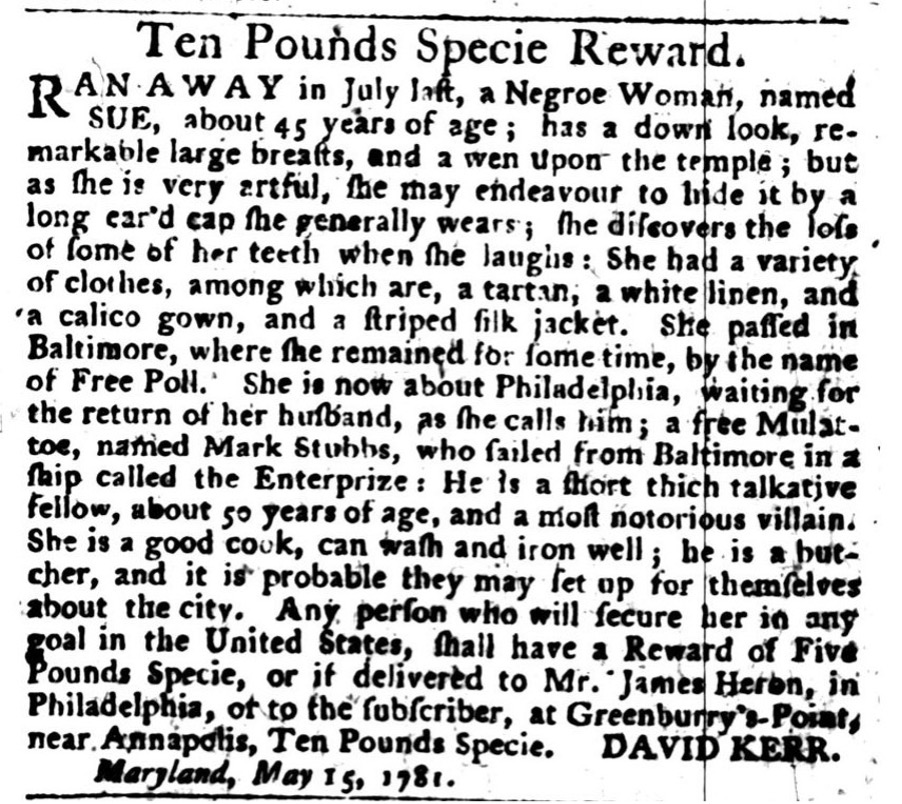

Billy G. Smith, “Free Poll (May 1781),” Freedom Seekers: Stories of Black Liberation in the American Revolutionary Era and Beyond, https://freedom-seekers.org/story/free-poll/ [accessed July 15, 2024].

Billy G. Smith, “Resisting Inequality: Black Women Who Stole Themselves in Eighteenth Century America,” in Carla Gardina Pestana and Sharon V. Salinger., eds., Inequality in Early America (Hanover, N.H: University Press of New England, 1999), 146-49.

Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, eds. Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisements for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728-1790 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989).

Lathan A. Windley, ed. Runaway Slave Advertisements: a documentary history from the 1730s to 1790, 4 vols. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983).

Major online collections of freely available freedom seeker advertisements include:

Freedom On The Move.

Discover Enslaved People in the Newspapers.

The Geography of Slavery in Virginia.

North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices, 1750-1865.

Runaway Slaves in Britain.

Runaway Slaves in Jamaica (I): Eighteenth Century.

This article originally appeared in September 2024.

Antonio T. Bly is the Peter H. Shattuck Endowed Chair at California State University, Sacramento. He has published several books and articles on people who escaped slavery, servitude, and marriage, including most recently “‘Indubitable signs’: Reading Silence as Text in New England Runaway Slave Advertisements,” Slavery & Abolition 42 (2021), 240-68.

Simon P. Newman is Emeritus Brogan Professor of History at the University of Glasgow, and an honorary fellow at the Institute for Research in the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His most recent book is Freedom Seekers: Escaping from Slavery in Restoration London (2022).

Billy G. Smith is Emeritus Malone Professor of History and Distinguished Professor of Letters and Science at Montana State University. He has published widely on class, poverty, and race in early America and the Atlantic World, including extensive work on freedom seekers. His recent publications include “Mapping Inequality, Resistance, and Solutions in Early National Philadelphia,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 110 (2021), 207-29.

Gloria McCahon Whiting is E. Gordon Fox Assistant Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. She is the author of Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England (2024).