Gangs, the Five Points, and the American Public

How can we teach Americans about our violent and sordid urban past? Certainly the movie Gangs of New York introduced countless Americans to the idea that the nineteenth-century city was an inhospitable place with crime, slums, and a core of violence that boggles the imagination. Gangs of New York was visually enthralling with a complicated love triangle and an overly simplistic plot that was more a mixture of The Godfather, Braveheart, and Gunfight at the OK Corral, than a reflection of the historical reality. The problem with the movie was that while it was evocative–with at times carefully detailed language and costume–it was wrongheaded in its historical narrative. The American movie public got no real sense of what it meant to live in the Five Points or what life was really like for any immigrant in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Martin Scorsese based his movie in part on Herbert Asbury’s The Gangs of New York, a sensationalist book that was originally published in 1927 and rushed into a new printing to capitalize upon the release of the movie. In fact, Thunder’s Mouth Press also published Asbury’s The Gangs of Chicago and The Barbary Coast hoping to build on the interest generated by the movie. These books are much the same: they are a compendium of horror stories from the American past highlighting the urban underworld. Asbury was a popular journalist who did a great deal of research for these books, but who did not always carefully separate fact from fiction. In one incredible section of Gangs of New York, Asbury recites the “history” of the mythical Mose, the Bowery B’hoy who existed on the stage and popular imagination, but not in reality. Facts, however, do not get in the way of Asbury’s prose. He declared that Mose’s favorite weapon was the butcher’s cleaver–reminiscent of Bill the Butcher of the movie–and that he was eight feet tall and that “his hands were as large as the hams of a Virginia hog.” Mose once pulled an oak tree from the earth and flailed out at the Dead Rabbit Gang of the Five Points “even as Samson smote the Philistines.” He could lift a horse car over his shoulders, swim the Hudson in two strokes and around Manhattan Island in six (32-33). Perhaps the reader is supposed to know that all of this description is fiction. But Asbury does not distinguish it as such and he so frequently gets information slightly awry or exaggerates events that his books are virtually useless as a guide to the past. All three books are packed with gory details of a poverty that drove men and women into crime. He relished telling us about this gang or that gang, describing great fights, chronicling the activities of prostitutes and the many dives that existed in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. But we are left incredulous and wondering where reality based in sources ended and fiction began.

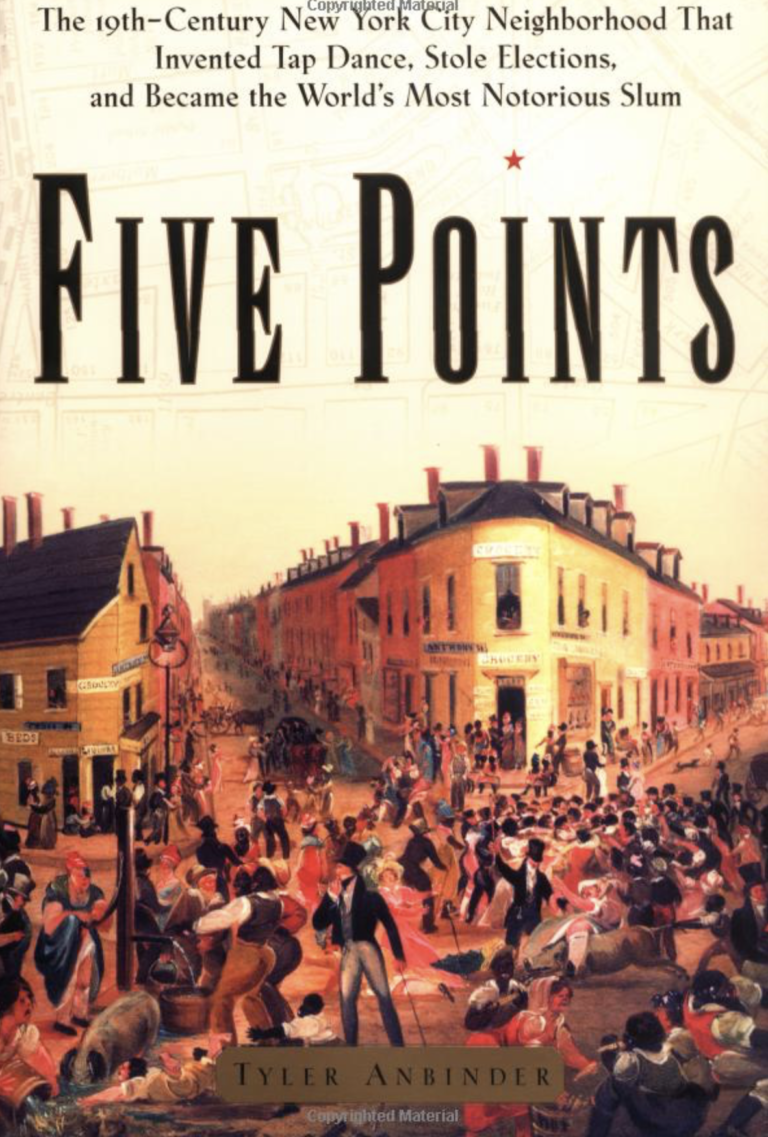

Neither the movie nor Asbury’s books help historians in getting Americans to understand the true nature of nineteenth-century urban America. Tyler Anbinder’s Five Points, however, offers us a better opportunity to introduce the general public to how historians understand the past. Based on prodigious research, Anbinder’s book is written for the all-too-elusive “educated reader.” Published by a commercial press, Anbinder’s book opens each chapter with a prologue that focuses on some story, usually about an individual, that highlights the thematic nature of the chapter that follows. The idea is to suck the reader in and get the reader thinking about thematic issues centered around America’s first great slum–the Five Points. The book begins with violence, always a nice hook for a popular audience, with a prologue on the 1834 race riot. Anbinder goes on to describe how Five Points became associated with crime and disorder. Anbinder builds a detailed socio-economic portrait of the Five Points as it developed before the Civil War. He describes the nature of Irish immigration, housing, working, politics, leisure, crime, and vice, and then religion and reform. He culminates this section of the book, which comprises the meat of his research and three quarters of the pages, with a return to violence in the 1850s and during the Civil War. The remaining one hundred pages describe the postbellum transformation of the Five Points with the influx of new immigrant groups–Italians and Chinese–and the initiation of urban renewal at the instigation of Jacob Riis.

As an academic I admire Anbinder’s achievement. Having used some of the same sources, I know how hard Anbinder has had to work to patch together a vivid picture of life in the Five Points. I wonder, however, if the effort has been worth it. Anbinder has filled his book with great stories of bare-knuckle fighting, barrooms, corrupt politics, and mayhem. There are also a host of great illustrations, including a color cover of an original painting of the Five Points that served as the model of the more frequently republished print that appeared on the cover of my first book. The detail and attractiveness of Anbinder’s book may or may not carry the general reader through more than 441 pages of text. But as an academic I am interested in what I learn that is new from a book and I want to see an author’s thesis that makes me think, “Gee, I wish I thought of that.” Anbinder states in his preface that he hopes “to set the record straight” about the Five Points. In this goal he succeeds both in the small and the large picture. For example, Anbinder convincingly argues, to the contrary of the movie Gangs of New York and Herbert Asbury, that there never was a Dead Rabbit’s Gang. More importantly, he demonstrates that while poverty and crime permeated much of the life of the Five Points, the immigrant groups who lived there strove for their piece of the American dream and ultimately succeeded in leaving the slum behind them. While recognizing that this thesis offers a corrective to the movie and Asbury, it is not a new idea for anyone familiar with the history of nineteenth-century urban America. Immigrant groups repeatedly crammed into city slums only to have the second generation succeed economically and move to better neighborhoods. In other words, Anbinder has only provided a case study for something we–the scholarly community–already knew.

Has Anbinder been successful in his other goal of reaching a popular audience? On April 15, 2003, I visited Amazon.com to get some means of answering this question. Anbinder’s hardcover book ranked 17,555, but his paperback was at 7,822. This ranking represents success by academic standards (and much better than the six-figure rankings of my own books), while Asbury’s Gangs of New York stood at 9,048. Unfortunately, millions have had their image of the Five Points warped by the cinematography of Martin Scorsese.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.4 (July, 2003).

Paul A. Gilje teaches at the University of Oklahoma. He is the author of The Road to Mobocracy: Popular Disorder in New York City, 1763-1834 (Chapel Hill, 1987), Rioting in America (Bloomington, 1996), and Liberty on the Waterfront: American Maritime Culture in the Age of Revolution which will appear in fall 2003.