“Garments,” “Glances,” “Limbs,” and “Rivulets”

Garments

Come closer.

Now the vast dusk recedes

toward the far reaches

of our remembrances.

This dust that I adore

was once a girl.

Her face a haze

romanced by many a long winter.

Eyes trellised in stone,

laughingly dashed with blonde.

Mad filaments, bridled—

stucco’d with birds, all over.

Resurrectionists loiter as our nimble ghost

casts off her weathered garments.

The grave cannot halt her magic.

Death warrants aren’t meant to be believed.

Not entirely. Not at first.

Such hardy animals, humans.

Blind sleepers, all the same.

Dauntless, her sylvan form descends,

bright-eyed and elastic with love.

Capture is a form of kindness,

so habit yourself to the dazzle

of her glossy limbs

adrift in loam,

her uncut hair

threaded with moss.

We are not so different, yet,

that we cannot wear each other’s clothes.

What’s left of me is only her,

effaced.

Appalachian origin fades to ornament—

grass-stained in transference,

a girl ago.

How wide a difference, still,

we lie — beyond.

Glances

Hasten, throat.

Unshut, mouth.

This house is now.

Decease calls, nonchalant

as one disembodied,

from behind a screen.

Memorials gloam as sleepers

blink in tandem,

their breath ripe with injury.

To delay evil is a kind of cure.

The curious diastole still

thrums her cautionary tale.

She only wins, who goes far enough.

The way is suspicious, the result slow.

Wait here, until the road unbends.

Don’t look back, only below.

In that violent hour,

even the grass was sepia,

half-lived in sieve and ruin.

Greensleeved, the radium girls

incarnate runaway decorum.

An unendangered bird

still chimes with wounds.

Enlist an archivist,

a gesture to permanence.

Hold fast to uncut glass

as gaudy species dazzle

your fleeted body,

limbic with mastery,

your weighted memory,

abducted by light.

Limbs

Go swarms,

elate your best array

in vacant rooms, unseen.

Last summer, when grass

was our mother tongue,

shy-eyed, our laps evaded

translation, and harvest.

We shunned haircuts and wine,

spoke only in verdant carols.

Now ether glistens in open air

and marrow blooms in glass.

The slain touch my mouth

with decoyed hands,

elbows knuckled to wrists

impossible to disentangle.

A slow hoard of indifference blooms

as we become our own aftermaths.

What rare species lies beyond,

raw-minded, untethered?

Surely some cure will appear

to cut the glow of fever dreams

and call us in, farther, from the fields.

Rivulets

All the lost ones glide silently by

wayward, ever-modern,

their fair reversals, postponed.

The grave is a fable, only.

Down a narrow aisle, amid thieves,

the plague work goes on.

Sisters sleep side by side

in ateliers of trivial breath,

lost in the float and odour of hair.

In our dead house,

rime beards the grass, leaving

footprints with no source.

Black lines creep as fields

unfold in sibilant chorales,

to gossip of the night.

Poetic Research Statement

Whitman once likened poets to spiritualist mediums, and that feels like the best place to begin.[1] My poetry has often, if not always, been the practice of listening intently to ghosts, both in a personal and a historical sense. These poems take that practice of spectral eavesdropping more than a few steps further, through the archive and into the harrows. They articulate a double history, overlaid and riddled with gaps, akin in some ways to a “ghost print” or cognate in monotype printing (a metaphor I like to imagine Whitman the journeyman would delight in). Monotyping produces a single, unique print. The ink erodes after the initial pressing, rendering subsequent reproductions inchoate. These four poems began as fragments, and remain marked by tiny voids of erasure. For I believe that poetry’s blank spaces, like history’s, have manifold stories to tell, well beyond the line’s end.

In the first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855), Whitman borrowed from the spiritualist language of haunting to narrate an ongoing dialogue with the dead. Over the next four decades, Leaves of Grass swelled to absorb “phantoms of countless lost” soldiers, continually evolving until the poet welcomed his own “soothing death” in 1892.[2] The first poem in the first edition, later titled “Song of Myself,” arises from Whitman’s encounters with his own and countless other unknown souls, echoing their fluency in dead tongues:[3]

O I perceive after all so many uttering tongues!

And I perceive they do not come from the roofs of mouths for nothing.

I wish I could translate the hints about the dead young men and women,

And the hints about old men and mothers, and the offspring taken soon out of their laps.

Despite the poet’s sweeping catalogs of the living and the dead, the human soul remains enigmatic, both “fathomless” and “untranslatable.” Yet, Whitman offers us glimpses of an ecoerotic afterlife where verdant cemeteries bloom with “the beautiful uncut hair of graves” and spiritual immortality depends on regeneration: “They are alive and well somewhere / The smallest sprout shows there really is no death.” Human particles decompose and re-emerge entirely altered, dispersed throughout the earth and finally incorporated into living bodies, to “filter and fibre your blood.” Perhaps more than any other poem in Whitman’s oeuvre, “Song of Myself” epitomizes the poet’s morbid optimism, assuring us that “All goes onward and outward . . . . and nothing collapses, / And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.” These lines remain, for me personally, the most comforting words conceivable in the first sorrows of mourning. I have returned to them again and again over the years, in the wake of untimely deaths. My oldest copy of Leaves of Grass, which originally belonged to my late father, now falls open, automatically, to these pages. “Has anyone supposed it is lucky to be born? / I hasten to inform him or her it is just as lucky to die, and I know it.” Though I have spent more than a decade of my life researching Whitman, the solace of this passage has never lost its sway over me.

Whitman observed the spiritualist movement with curiosity, and, at least initially, classed it as a science alongside anatomy and chemistry. In a self-authored review of the 1855 edition, the poet described himself as “the true spiritualist. He recognizes no annihilation, or death, or loss of identity.” Bodily transcendence was a central tenet of the spiritualist faith, which promised followers the chance to escape the constraints of their material forms. Whitman’s poetics of “merging” with others echoes the medium’s claim to disembodied communication:

This is the press of a bashful hand . . . . this is the float and odor of hair,

This is the touch of my lips to yours . . . . this is the murmur of yearning,

This is the far-off depth and height reflecting my own face,

This is the thoughtful merge of myself and the outlet again.

For Whitman, the aims of the poet and those of the medium were closely aligned: both act as magnetic forces for the attraction of spirits that defy death. Mediumship is, at its heart, an invitation. The medium must be willing to be occupied by the ghost.

Like its author, Leaves of Grass endures with the tenacity of an archetypal echo, capturing something of the sense of American possibility, that uncanny duality of purpose and longing that has haunted the national consciousness. To envision Whitman’s idealized democracy alongside late capitalist reality is to experience a historical vertigo, a fall from the transcendental and ecoerotic to the hyper-violent and virtually (un)real. And yet, Whitman’s “tomb leaves” remain imprinted upon the cultural memory of the nation, as though he actually managed to conjure his own mirthful ghost, who haunts us still, somewhere just out of reach:

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you

Written to mark the bicentennial of Whitman’s birth, my poems operate within that lacuna, occupying the dissonant threshold between Whitman’s optimistic vision for America, “out of hopeful green stuff woven,” and my own personal history. I come from a rural Kentucky landscape still graced with sublime natural beauty, yet increasingly scarred by industry, agribusiness, addiction and inequality. One of the questions my poems orbit is how to widen the elegiac form to mourn geographically and culturally, and whether such collective expressions of grief could possibly be a precursor to change. In this sense, I am profoundly curious about Whitman’s capacity to move beyond the inertia of deep mourning, into the territory of generous melancholy.

Far removed from Freud’s pathologization of melancholia as a failure to mourn, Whitman’s poetics of traumatic regeneration and his personal capacity for resilience recall the early-modern concept of generous melancholy, and foreshadow the psychological phenomenon now known as post-traumatic growth, a concept designating the unexpected benefits, now empirically measured, that often follow adverse experience.[4] In De Triplici Vita (Three Books on Life, 1480), Marsilio Ficino resurrected the Aristotelian concept of melancholy genius. As Christina Cavedon observes,”Ficino claimed that all thinkers predestined for greatness suffer from a favorable form of melancholia which has become known as “melancholia generosa.”[5] In Ficino’s view, this generous melancholy catalyzes transcendence over the physical body and its transient experiences of suffering. Simply put, generous melancholy calls on us to overcome “dark dejection” through action and art.[6] The parallels between Ficino’s theory and Whitman’s poetic landscape of transcendent decay are manifold. I believe that Whitman’s legacy is irrevocably linked to the “dark bequest” of his own regenerative melancholy: his ability to turn from acute suffering to empathic action, and then, finally, to writing.[7] Whitman offers a riveting case study, both personally and poetically, of humanity’s regenerative potential.

Whitman wrote in harrowing personal and political circumstances. He wrote through war, poverty, pain, paralysis, and depression. He wrote on scraps of recycled advertisements when paper was scarce. He stitched handmade notebooks to carry in his pockets while tending wounded soldiers in the Civil War hospitals. He wrote while mourning the deaths of three siblings, his beloved mother, his volatile father, and countless soldiers, collectively elegized in Leaves of Grass. Throughout the post-bellum decades, he continued to write as his body failed and his mind lost something of its clarity.

Whitman expanded and revised Leaves of Grass for almost 40 years. For much of that time, he attained only a modest audience. Reviews of the first edition were mostly scathing (excepting Whitman’s pseudonymous self-promotions and Emerson’s famous letter). While the “good grey poet” began to gain global recognition in his twilight years, widespread fame, as usual, was posthumous. I find solace in Whitman’s prolific literary output and his resilience in the face of criticism, most of all in his refusal to be silenced by either personal tragedies or political crises.

While I can’t claim to have been in dialogue with Whitman in a spiritualist sense, I did write these poems in thrall not only to him, but also to the lesser known figures in his orbit whose archival traces I encountered in my research. The phantom limbs that haunted Whitman’s specimen soldiers recur throughout my poetry as a metaphor for the physicality of mourning and the impossibility of severing attachments to our dead beloveds. Joseph Leidy, the Civil War surgeon who bound his own anatomical treatise in the skin of a soldier whose body he autopsied, was the inflammatory catalyst for my twelve-poem suite, “An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy.”[8] His legacy is unsettled by the arrival of a contemporary female narrator who reimagines her own body as host to a haunted palimpsest—a dialogue between male and female, body and soul, doctor and patient—that slips between their century and ours.

The archive has always been a generative place for me, as a poet. While researching The Afterlives of Specimens: Science, Mourning, and Whitman’s Civil War (2017), I spent a great deal of time in archives, particularly the Library of Congress and the Mütter Museum / College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The collections of both these institutions were integral to Afterlives, but while I was working in Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, something else happened. I found myself haunted by artifacts (letters, ephemera, diaries, photographs) that did not fit neatly within the narrative of the book I was there to write (at least not in any tangible, linear sense). And yet, they would not let me go.

While undertaking these residencies, I intended to set all my other writing projects aside. The clock ticks loudly during a research fellowship. Especially when one lives in Australia but writes on American literature and culture: accessing the relevant archives entails a transpacific flight and months away from home. So, I’d intended to focus my attention solely on material that would uphold the thesis I planned to lay out in The Afterlives of Specimens. But that is not what happened. Poems began to emerge, usually very early in the morning or late at night. In the end, I wrote both books simultaneously. And I feel certain, with the benefit of hindsight, that I could not have written one without the other.

My first poetry collection, Calenture, came out a few months after Afterlives. The title recalls Whitman’s “grass of graves” and his lifelong fascination with shipwrecks (although, strange as it sounds, I must confess to realizing the later influence only recently). “Calenture” is an archaic medical term for a tropical fever incident to sailors who suffered from a potentially fatal hallucination: they saw the sea as green fields. If left unrestrained, many were compelled to leap to their deaths, so great was their desire to touch the fever’s grassy mirage.

I initially conceived of Calenture as a collection of elegies, in the broadest and most amorphous sense of the word. The book is ossuary to my own constellation of deaths, some sudden, all strange. The loss of my sister, Amanda, is present on every page. It is also a catalog of the medical and mercurial oddities I encountered in archives, curiosities that call forth the exquisite corpse hard at work beneath our living flesh. The phantom limb. The wandering womb. The book bound in human skin. The face that ghosts itself. The fever dream that ends in drowning. The writhing grace of speaking in tongues.

Continuing the practice of merging archival poetics with personal histories, these four poems began with selected fragments from Whitman. Sometimes I chose lines that have long held resonance for me. Whitman’s “beautiful uncut hair of graves” recurs in “Garments” as “her uncut hair / threaded with moss.” At other times I chose phrases that were lyrically compelling, and tried to create a new context for them. For example, I found the line “stucco’d with quadrupeds and birds all over” so oddly evocative that I used it to describe the spectral sister in “Garments”:

Her face a haze

romanced by many a long winter.

Eyes trellised in stone,

laughingly dashed with blonde.

Mad filaments, bridled—

stucco’d with birds, all over.

I also made small alterations that shift meaning, slips of the tongue (that architect of speech that is so significant to Whitman). The above passage fuses two of Whitman’s line openings from “I Sing the Body Electric” (1855): “Mad filaments” and “Bridegroom-night.” Now the groom is lost and the filaments’ madness is tethered by a bridle, embellished with birds. For anyone who wants to further disentangle Whitman’s words from mine, The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, is a vast online resource that hosts an excellent search engine.

The titles arose from Whitmanian themes that I discuss in The Afterlives of Specimens. “Glances” references Whitman’s “A Backward Glance O’er Travel’d Roads” (1888). It is also a meditation on nostalgia, a diagnosis commonly used by Civil War doctors to describe symptoms that would today be attributed to traumatic stress. The Union Army’s Manual of Instructions for Enlisting and Discharging Soldiers (1863) defined nostalgia as “mental disease” within “the class of Melancholia,” characterized by an “unconquerable longing for home” that often proved fatal.[9] From its inception as a disease of the body, nostalgia was embedded within the psyche: the physical manifestation of desire for an impossible return, a longing not for a specific location, but for an interior geography that is ephemeral in its very nature.

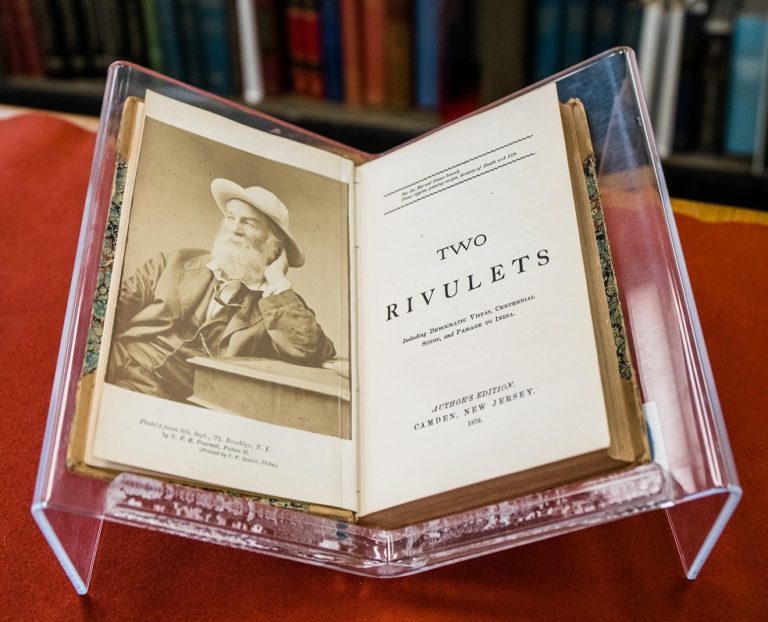

“Rivulets” occupies a haunted rural landscape that doubles as a field hospital. We’ve become so used to the phrase “battlefield” that it has lost its uncanny literality, an eeriness captured in Timothy H. O’Sullivan’s photograph of Gettysburg, “A Harvest of Death.” Whitman’s Memoranda During the War (1875-76) draws on agrarian metaphors to describe the war’s carnage: “the numberless battles, camps, hospitals everywhere— the crop reap’d by the mighty reapers.”[10] “Rivulets” recalls the long rows of cots that pervade Whitman’s hospital notebooks, but they are overlaid onto the fields of my Kentucky girlhood, fraught with their own dangers.[11]

“Garments” is the most personally revelatory and specifically elegiac, and so I will say the least about it. The title nods to Whitman’s strange assertion, “agonies are one of my changes of garments.” To me this line embodies a startling dissonance. There is something unsettling, perhaps even frightening, about this shapeshifting sufferer that I wanted to explore. On the other hand, it can be read as comforting in the sense that suffering is ephemeral, because our bodies themselves are transient.

“Limbs” draws on Whitman’s accounts of amputee soldiers suffering from phantom pain. His hospital notebooks document the neural hauntings that followed amputations, such as the case history of “Thomas H. B. Geiger, co. B 63rd Penn, wounded at Fredericksburg . . . young, bright, handsome Penn boy—tells me that for some time after his hand was off he could yet feel it—could feel the fingers open and shut.”[12] I find phantom limb to be a powerful symbol for the physicality of grief—an attachment rendered acutely present in its absence. Contemporary neurological research confirms what Civil War soldiers intuited: the phantom is its own entity, no longer tethered to its formerly physical incarnation. As Cassandra S. Crawford explains, “phantoms are today conceived as parts not accountable to gravity, symmetry, time, or the principles of human morphology, not answerable to the laws that had always governed the physiology of human bodies.”[13] So too it is with mourning: our love for those who are no longer alive is not beholden to gravity, symmetry, time, or human morphology. Death does not inhibit desire. Our kinship does not end when the beloved takes her final breath. We are bound to the dead by constellations of attachments that remain unsevered. For me, the cultivation of such enduring love is reverential and deliberate. Melancholic, some might say.

Author’s Note

All editions of Leaves of Grass cited below were digitally sourced from The Walt Whitman Archive, an open-access online resource that allows readers to view the various editions as they were printed in Whitman’s lifetime, alongside a vast and ever-expanding curation of scholarship, correspondence, and biography.

About the Author

Lindsay Tuggle is the author of The Afterlives of Specimens: Science, Mourning, and Whitman’s America (2017). Her debut poetry collection, Calenture (2018), was named one of The Australian’s “Books of the Year” and was Highly Commended in the Anne Elder Award for poetry. Lindsay lives in Sydney with her husband, Michael, and a tyrannical rescue parrot named Kato.

________________

[1] Between the publication of the first and second editions, Whitman became fascinated with the phenomenon of spiritualism, and attempted for an entire year to train himself as a medium, modelling his practice after the famous medium Cora Hatch. See Molly McGarry, Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 169-170. Whitman eventually became disenchanted with spiritualism, or at least with some of its proponents. See Jerome Loving, Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 353.

[2] Leaves of Grass (New York: W. E. Chapin, 1867), 10b.

[3] All poems were originally untitled in the first edition (1855). I have used their best-known titles for clarity. Except where indicated otherwise, all quotations I take from Leaves of Grass in this statement come from the 1855 edition, Leaves of Grass (New York: 1855).

[4] Freud’s binary division between mourning and melancholia (which he later reconsidered after his daughter’s death) is critiqued at length throughout my book, The Afterlives of Specimens. The psychological field of post-traumatic growth studies is rapidly expanding. As Ann Marie Roepke and Martin Seligman explain: “Adversity may lead to surprising benefits as well as to unsurprising damage. Philosophical and religious texts have discussed the transformative power of suffering for millennia. More recently, psychologists have examined this phenomenon through an empirical lens, measuring, describing, and predicting the positive changes that can follow adverse experiences. These changes are referred to as post-traumatic growth. . . . Such growth has been documented following sexual assault, life-threatening illness/injury, and combat.” “Doors Opening: A Mechanism for Growth after Adversity,” The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10:2 (2015): 107. See also Richard G. Tedeschi and Lawrence G. Calhoun, “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence,” Psychological Enquiry 15:1 (2004): 1-18.

[5] Cultural Melancholia: US Trauma Discourses Before and After 9/11. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill, 2015), 48-49.

[6] Immanuel Kant, Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime, trans. John T. Goldthwait (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960), 64. On Kant’s virtuous melancholy, see Gregory R. Johnson “The Tree of Melancholy,” Kant and the New Philosophy of Religion, ed. Chris L. Firestone, Stephen Palmquist (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), 43-47.

[7] Leaves of Grass (Philadelphia: McKay, 1891–92), 415.

[8] For more on Leidy and anthropodermic bookbinding, see Lindsay Tuggle, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science, Mourning, and Whitman’s Civil War (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2017) 87-92; and “The Autopsy Elegies,” Journal of Poetics Research 8 (2018).

[9] Roberts Bartholow, A Manual of Instructions for Enlisting and Discharging Soldiers (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1863), 21.

[10] Memoranda during the War (Camden, N.Y.: Author’s publication, 1875–76), 57.

[11] This title also references Whitman’s “Autumn Rivulets,” a section of Leaves of Grass that first appeared in 1881.

[12] Tuggle, The Afterlives of Specimens, 101-102.

[13] Phantom Limb: Amputation, Embodiment and Prosthetic Technology (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 33.

Further Reading

Christina Cavedon, Cultural Melancholia: US Trauma Discourses Before and After 9/11 (Leiden, the Netherlands, 2015).

Cassandra S. Crawford, Phantom Limb: Amputation, Embodiment and Prosthetic Technology (New York, 2014).

Ed Folsom, “Walt Whitman and the Civil War: Making Poetry Out of Pain, Grief, and Mass Death.” Abaton 2 (Fall 2008): 12–26.

Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, eds., The Walt Whitman Archive.

Michael Ann Holly, The Melancholy Art (Princeton, 2013).

Molly McGarry, Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley, Calif., 2008).

Kenneth M. Price, To Walt Whitman, America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2004).

Jennifer Radden, ed., The Nature of Melancholy: From Aristotle to Kristeva (Oxford, 2000).

David S. Reynolds, Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (New York, 1995).

Ann Marie Roepke & Martin E.P. Seligman, “Doors opening: A Mechanism for Growth after Adversity.” The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10:2 (2015): 107-115.

Richard G. Tedeschi and Lawrence G. Calhoun, “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence.” Psychological Enquiry 15:1 (2004): 1-18.

Lindsay Tuggle, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science, Mourning and Whitman’s Civil War (Iowa City, 2017).

Lindsay Tuggle, Calenture (Melbourne, 2018).

www.whitmanbicentennialessays.com

This article originally appeared in issue 19.1 (Spring, 2019).

Lindsay Tuggle is the author of The Afterlives of Specimens: Science, Mourning, and Whitman’s America (2017). Her debut poetry collection, Calenture (2018), was named one of The Australian’s “Books of the Year” and was Highly Commended in the Anne Elder Award for poetry. Lindsay lives in Sydney with her husband, Michael, and a tyrannical rescue parrot named Kato.