“Gettysburg Wasn’t His First Address”

Kentucky’s Belated Embrace of Abraham Lincoln

Earlier this year, Skyler Hornback, a 12-year-old from Sonora, Kentucky, racked up $66,600 on a single day during Jeopardy‘s Kid’s Week competition. His feat made minor national news because his winnings amounted to the third-highest one-day total (for kids and adults) in the game show’s history. During his mid-show interview with host Alex Trebek, the affable, bespectacled Skyler professed his fascination with all things related to Abraham Lincoln. “Lincoln is a very intriguing figure because most people think they know him when they really don’t,” Hornback asserted. “There was just so much behind that beard and top hat that people just don’t realize.” He informed Trebek of his ability to recite the Emancipation Proclamation from memory. As luck would have it, the Final Jeopardy! category turned out to be “The Civil War.” Confident in his knowledge, Hornback wagered $30,000, and responded to the question: “Abraham Lincoln called this document which took effect in 1863, ‘A fit and necessary war measure,'” with the correct answer: the Emancipation Proclamation.

In some ways it does not seem surprising that a young man with a penchant for historical knowledge might know a lot about the United States’ sixteenth (and arguably most famous) president, especially when he has grown up in Larue County, Kentucky, the back yard of Lincoln’s birthplace, and graduated from Abraham Lincoln Elementary. But among white Kentuckians, such youthful ardor for Lincoln is a relatively recent phenomenon. Hornback’s generation may be the first in the history of the state to share both a widespread awareness and pride in their state’s claim to the “great Emancipator.”

For well over a century after Lincoln’s death, white Kentuckians were disdainful, hostile, or just plain disinterested in highlighting the role their state had played in the life of the iconic president. While these attitudes began to change in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement and the revisionist Civil War history it spawned, in the early twenty-first century this trend coalesced into a whole-hearted celebration of the 200th anniversary of the president’s birth. Between 2008 and 2010, Kentuckians feted Lincoln with galas, ceremonies, monuments, and highway signage that highlighted his Bluegrass State heritage. In doing so, they were not simply recovering a native son, but also turning their backs on a Confederate identity they had embraced for the past 150 years. They re-cast the state’s Civil War era narrative, and finally chose to remember and raise the public consciousness of painful and complicated historical topics such as slavery and emancipation.

The generous outpouring of affection Kentuckians showed him during the bicentennial would certainly have surprised Lincoln if he had been around to see it.

The generous outpouring of affection Kentuckians showed him during the bicentennial would certainly have surprised Lincoln if he had been around to see it. He was born in 1809 in a tiny log cabin located near Hodgenville, in the lush, rolling hills of central Kentucky. A few years later, the Lincoln family moved to a second cabin at nearby Knob Creek, and they remained there until Thomas Lincoln moved his family to Indiana in 1816 when Abraham was only seven.

The fact that Lincoln married a Lexingtonian, Mary Todd, and understood well the habits and views of white Kentuckians did not help his popularity in the state during his political career. In the summer of 1860, as he was running for president, he wrote to a resident of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, who had asked him to campaign there: “You suggest that a visit to the place of my nativity might be pleasant to me. Indeed it would.” Then he joked, “But would not the people lynch me?”

At the heart of white Kentuckians’ dislike of the Republican candidate was his untrustworthy position on slavery—his insistence that the Constitution bound the government to protect slavery where it existed, but that the government should prohibit the spread of the institution to all new territories and states. This did not suit most white people in a state strongly wedded to the peculiar institution. Though a plantation economy did not dominate the state, many white Kentuckians depended on slaves to assist them in their small-scale agricultural and industrial endeavors. Twenty-eight percent of all Kentucky households owned slaves in 1860, and many more relied on hired-out slave labor, so the economic and cultural attachment to slavery was very strong in the Commonwealth.

As a consequence, while Lincoln may not have been in danger of losing his life to angry Kentuckians in 1860, he was not in danger of winning their votes, either. That November, most of the state’s white men proved their allegiance to latter-day Whiggery and to Unionism by voting for Constitutional Union candidate John Bell. Lincoln captured fewer than two percent of their votes, and only two voters in Mary Todd’s hometown cast their ballots for him. In early 1861, with secession sentiment swelling throughout the South, the victorious Lincoln penned some remarks that he hoped to deliver in Kentucky on his way to take office in Washington, D.C. He got as close to the state as Cincinnati, just over the river, but he never got to deliver his message appealing to Kentuckians to remain loyal in the face of his election. “Who amongst you would not die by the proposition that your candidate, being elected, should be inaugurated soley on the conditions of the Constitution, and laws, or not at all?” he had planned to ask them. “What Kentuckian, worthy of his birthplace would not do this? Gentlemen, I too, am a Kentuckian.”

Most white Kentuckians would have been loath to acknowledge solidarity with the incoming president based on his natal origins. They did, however, cling to the Union and to Lincoln’s promise to protect slavery where it existed. Indeed, for many Kentuckians, the conviction that the Union would continue to be the best protector of slavery—as it had for over eighty years—inspired their loyalty. In turn, as the war began, Lincoln trod very lightly in his handling of his birth state. He respected the state’s early policy of neutrality and once famously explained: “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.” In the face of strategic and tactical needs on the part of both the Union and Confederate armies, neutrality became impossible to maintain. Luckily for Lincoln, the tradition of Unionism in Kentucky was a strong one, and by the war’s end the number of Kentucky white men who fought for the Union was at least twice that who had fought for the Confederacy.

Thus, from the beginning of the conflict, the loyalty of white Kentuckians to the Union was precarious and patchy. Many civilians aided Rebel forces, compelling the Union military government, which occupied the state beginning in September 1861, to crack down on disloyal activity. People suspected of Confederate sympathies could neither hold elected offices nor serve as teachers, ministers, or jurors. Federal authorities suspended freedom of the press. Despite Lincoln’s kid-gloved approach, many white Kentuckians—even loyal ones—became resentful of what they saw as federal interference in civilian affairs.

Of course, what really caused whites to turn against Lincoln as the war dragged on was his evolving position on slavery. Kentuckians were well represented in the group of border state congressmen Lincoln called to meet with him at the White House in 1862 to discuss a plan for compensated emancipation in their states. The state legislature appointed a committee to respond to the proposition and they pledged to combat the plan “by all peaceable means,” and promised that should that course of action fail, “Kentucky [would] rise up as one man and sacrifice the property, and, if need be, the lives of her children in defense of the Constitution under which alone we can ever hope to enjoy natural liberty.” When Lincoln, having given up hope of conciliation, forged ahead with his emancipation policy, they rejected him too.

After Lincoln issued the preliminary emancipation proclamation in September 1862, Benjamin Buckner, a major in the 20th Kentucky Volunteers, described it as “an abominable infamous document, [which] falsifies all his pledges both public and private.” “The Union Kentuckians are most shamefully treated,” he exhorted, “and by reward of the presidents want of good faith, which is only equaled by his lack of sense, we find ourselves in arms to maintain doctrines, which if announced 12 months ago, would have driven us all, not withstanding our loyalty to the Constitution & the Union, into the ranks of the Southern Army.” He resigned his commission in the Union Army and went home for the duration of the war. In January 1863, John Harrington of the 22nd Kentucky wrote to his sister in dejected tones: “I enlisted to fight for the Union and the Constitution, but Lincoln puts a different construction on things and now has us Union Men fighting for his Abolition Platform and thus making us a hord of Subjugators, houseburners, Negro thieves, and devastators of private property.”

White hatred of Lincoln only increased when he began enlisting enslaved African American Kentuckians in the Union Army. One of the Commonwealth’s most venerated Union warriors, cavalry commander Frank Wolford, exclaimed in 1864 that people of Kentucky would refuse to “keep step to ‘the music of the Union’ alongside of negro soldiers.” Throughout the spring and summer of that year, Wolford made a series of long-winded speeches—one purportedly lasting for four hours—in which he denounced Abraham Lincoln as a “fool” and a “tyrant,” and his policy of enlisting African Americans as illegal and “disgraceful to the people” of Kentucky. He encouraged white Kentuckians to resist any efforts to enroll them in the Army. Wolford’s series of extended protests led to his arrest and dishonorable discharge from the Union Army, and elevation to the status of folk hero among many in his home state. One Bluegrass resident noted, “Whilst the policy of his course is doubted, even censured by some, the gallant Wolford is now the most popular man in our part of the State & the President universally condemned for his tyrannical course in dishonorably dismissing [him].”

Such anti-Lincoln sentiments were common among white Kentuckians on the homefront as well. Western Kentucky resident Ellen Wallace’s husband owned around thirty slaves at the outset of the war, but initially she remained a staunch Unionist who in April 1861 projected that any decision by Kentucky to secede would lead to the state’s “ruin.” But over the next two years, Wallace came to believe that ruin came to Kentucky anyway in the form of Abraham Lincoln (a “vile wretch” of a president) and his “infamous proclamation.”

Over the course of the war, Wallace repeatedly confided in her diary in vividly racist terms her fears of the physical harm and sexual threat that emancipation would bring to the women of Kentucky. Wallace charged Lincoln with placing “innocent women and helpless infants at the mercy of black monsters who would walk in human shape.” “Servile insurrection will be the consequence [of emancipation] unless the strong arm of the nation prevents it,” she wrote on another occasion, “and the blood of helpless women and children will flow in torrents if [Lincoln’s] wicked and fanatical policy is not over ruled.” It could be, Wallace feared, “St. Domingo all over again.” As African Americans assumed authority within the Union Army, Wallace complained that Lincoln had “made the negro master of the white man as far as his power goes putting arms in their hands … the white man has to turn his horses head and obey Lincoln’s negro troops with clenched teeth.” In the diaries and letters of many Kentucky Unionists, Lincoln was a villain, responsible for corrupting their understanding of the war’s true purpose, which was to save the Union. They directed much of their anxiety, frustration, and anger surrounding the war and its outcome at him.

Not surprisingly, Lincoln did not fare much better in the estimation of most Kentucky whites after the war. While the many locales in other victorious Unionist states rushed to commemorate the martyred president, white Kentuckians did their best to honor the dead Confederacy of which they were never a part. In the decades following the war, they built Confederate monuments, published sectional periodicals, participated in veterans’ organizations and historical societies, and produced literature that portrayed Kentucky as Confederate, while largely ignoring the Union cause and the feats of its soldiers. In the seventy years following the Civil War, for instance, Kentuckians erected over seventy Confederate monuments within the state, and fewer than ten monuments to the Union. Many white Kentuckians embraced the conservative political, social, and racial values embedded in the Lost Cause even when they had not supported the Confederacy during the war, rejecting the legacies of both the Union and its president.

Americans outside of the Commonwealth, however, began to turn their attention to the martyred president’s Kentucky heritage. In the nascent age of American tourism, several people quickly realized that Americans would want to visit Lincoln’s birthplace. In 1894, New York restaurant owner Alfred Dennett purchased the Sinking Spring Farm near Hodgenville, where Lincoln was born and lived until the age of two. He moved a dilapidated cabin found a couple of miles away from the farm, rumored to have been the Lincolns’, to the site. As he struggled to finance his Lincoln endeavor, Dennett purchased another decaying cabin in southern Kentucky purported by locals to be the residence in which Jefferson Davis was born. Capitalizing on the national mood of sectional reconciliation, Dennett disassembled both cabins and began displaying them at public expositions in Tennessee, New York, and elsewhere.

Much to the chagrin of historians, but unintentionally underscoring the extent to which Americans longed for post-Civil War reconciliation, the logs of the two structures purportedly became confused and intermingled during the constant disassembly and re-assembly. As famed muckraker and Lincoln enthusiast Ida Tarbell later wrote, “It was the money-makers who first laid hands on the Lincoln cabin. It was torn down, dragged about the country, and shown in settings so vulgar and inappropriate that it was made to seem almost a ridiculous thing.”

Dennett could never raise the necessary funds for his grandiose scheme (which included a spa and hunting lodge), and in 1905 he sold the Sinking Springs site to Robert Collier, the editor and publisher of Collier’s Weekly, for $3,600. Collier had founded the Lincoln Farm Association the year before with the purpose of making Lincoln’s homestead a national shrine, to “perpetuate it as a birthplace of patriotism,” and to attract visitors from all over the country. The New York-based association purchased the Lincoln (/Davis) cabin for $1,000, shipped it back to the Lincoln farm in Kentucky and commissioned architect John Russell Pope to design a marble building to house and protect it. The monument plans included fifty-six steps, one for each year of the president’s life, which led up to the columned portico and heavy bronze doors of the marble structure.

Collier hoped to dedicate the project in time to mark the centenary of Lincoln’s birth in 1909. Rather than a political beacon of Unionist victory, however, the association intended the homestead to represent national reconciliation. They hoped that since it laid upon “almost the centre of our population,” it would become “the most accessible national shrine … the Nation’s Commons, the meeting-place of North and South, of East and West, a great national school of peace and unity, where all sectional animosity will forever be buried.”

Accordingly, the effort to mark Lincoln’s birthplace began and ended largely as a national effort, rather than a local project. Of the $100,000 the Lincoln Farm Association had raised in 1908, only $4,000 came from the Kentucky legislature (in contrast, Kentucky lawmakers appropriated $15,000 for the state’s Jefferson Davis monument, which was dedicated in 1924). Eventually, over 80,000 Americans joined the LFA. The association intended that the monument for the people should be a truly populist undertaking and asked that individuals contribute no more than twenty-five dollars, suggesting an ideal subscription rate of twenty-five cents. In the end, an estimated two-thirds of the funding needed for the project came in quarters.

In 1908, the state of Kentucky did form a Lincoln Centenary Committee, headed by prominent Louisville Union Army veteran Andrew Cowan. In the spirit of sectional reconciliation, the committee included some of Kentucky’s most esteemed citizens, both former Unionists and Confederates. In a rare occasion of cooperative interracial memorialization, Kentucky African Americans also took part in the centennial remembrance. Governor Augustus Willson, only the second Republican governor in the state’s history, appointed a “Negro People’s Centenary Committee,” after deeming that “the negro people should have honored representatives present to bear witness to their love for Abraham Lincoln and their faithfulness to his memory and to be a part of the great scene just as they are a part of the great life of our country.”

By including African Americans in the memorial effort, Governor Willson recognized the important place Abraham Lincoln occupied in black historical memory, and sought to emphasize “the ideal of blessed humanity which freed a race, and which is such a noble part of [his] life.” But inclusion did not mean equity. White organizers considered the black committee a separate entity and did not list its members on the state committee’s letterhead, or even in the official Lincoln Centenary Program, thereby relegating African Americans to the status of silent partners within Kentucky’s efforts to remember the Civil War.

The cornerstone laying ceremony featured a “Confederate Escort Committee,” which stood alongside Union veterans in the ceremony. John Leathers, one of the Confederate veterans involved, considered the event a success and wrote Andrew Cowan afterwards that, “all passion and prejudice [had] gone with the flight of the years and we are now one reunited people with one flag and one country and common destiny and I think I can safely say that none among the great crowd present at the Lincoln Farm on the 12th were more sincere and honest in rendering tribute to the name and fame of the immortal Lincoln than the Ex-Confederates who were gathered there.”

Amidst the reconciliationist overtones of the endeavor, it was President Theodore Roosevelt who articulated the most radical form of Unionism. In the keynote address he delivered at the ceremony, he lauded Lincoln, the “homely backwoods idealist,” for saving the nation when he freed the slaves. Roosevelt praised the native Kentuckian’s “love for the Union,” as well as his “abhorrence of slavery,” calling him an “apostle of social revolution.” Roosevelt brought up a Civil War legacy rarely acknowledged in Kentucky, where what little white public memory of Union victory that existed concentrated on its military victory rather than the social and racial revolution it brought. Roosevelt’s mention of the “radical revolution,” let alone his celebration of it, was an anomaly in white memory in the state.

In 1961, acclaimed Kentucky-born author Robert Penn Warren provided a much more representative description of the way many white Kentuckians remembered Lincoln. Reflecting on his early twentieth-century childhood growing up in Guthrie, Kentucky, during which he absorbed the “ever-present history” of the Civil War, he reminisced: “I had picked up a vaguely soaked-in popular notion of the Civil War, the wickedness of Yankees, the justice of the Southern cause (whatever it was; I didn’t know), the slave question, with Lincoln somehow a great man but misguided … I got [my impression] from the air around me (with the ambiguous Lincoln bit probably from a schoolroom).”

Warren’s recollection reflected the power that pro-Confederate groups, especially the United Daughters of the Confederacy, had over the interpretation of the Civil War in Kentucky. Not only did the UDC shape the state’s cultural landscape with their memorial days and monument campaigns, but their production of state textbooks and the supplemental pro-Confederate texts ensured that no child in Kentucky public schools could have anything but an “impartial” view of the conflict between the states.

In 1901, the Lexington chapter installed pictures of Robert E. Lee in every public school in the city. Later that year, the UDC held a public ceremony in which the members presented the same schools with portraits of Jefferson Davis on the same day as the Grand Army of the Republic unveiled its portraits of Lincoln. Newspaper accounts reflected the disparity in the esteem in which the city’s white masses held the two men. Even the Republican Lexington Leader covered the stories in two separate columns, devoting to the UDC twice as much space as the GAR. The paper called the UDC ceremony “unique,” “an impressive program,” and “an important patriotic event.” The GAR donation, by contrast, was relegated to the “social and personal” section of the paper, where it was deemed “very acceptable and much appreciated.”

Although the Lost Cause held sway in Kentucky’s schools, monuments to Lincoln slowly began to appear in town squares and other civic spaces. The state constructed a large statue of Lincoln in the Hodgenville town square in 1909. Two years later, Governor Willson persuaded Louisville businessman James Breckenridge Speed (whose uncles Joshua Fry Speed and James Speed were Lincoln’s close friends and political allies) to donate $40,000 to pay for a Lincoln statue for the state Capitol rotunda. President William Howard Taft came to Frankfort to unveil it.

Local Kentuckians took note of the economic boon afforded by Lincoln’s birthplace, which became the Lincoln National Historical Park in 1916. When Ida Tarbell traveled through the area in the 1920s to research her book, In the Footsteps of the Lincolns (1924), she found that “Like Homer in Greece, Lincoln in Kentucky was claimed by, if not seven, at least several different places.” At the aptly named Poortown, where the log cabin of Abraham’s uncle Mordecai Lincoln once stood, the locals, who knew “the value of a Lincoln connection,” were happy to show Tarbell around. “They tell you there, with every proof of conviction, that here Abraham Lincoln was born; and that all Poortown feels naturally enough that it is wrong indeed that the noble marble monument that stands in Hardin County, near Hodgenville should not be theirs, that they should not have enjoyed the increase in land values that Hodgenville has had, and that they should not have the roads that the Lincoln Memorial has brought to Hardin County.”

In an extension of Kentucky’s wartime antipathy toward Lincoln, however, public memorialization of the president was largely limited to African American Kentuckians who celebrated him as part of Emancipation Day events, and by hanging his image inside their houses. Their most visible means of acknowledgment were the several segregated Common Colored Schools they named after him around the state. Even these tributes became obsolete after schools desegregated in the 1960s and many African American schools closed. According to historian David Rapaport, as of 2002, of the 1,353 public schools in Kentucky, Lincoln’s name appeared on only eight, which makes him the namesake of a mere six-hundredths of one percent of the schools in the state of his birth.

While white resistance to the demise of Jim Crow in the 1960s and 1970s seldom appeared as violent or extensive as it did in states farther south, public acknowledgment of Kentucky’s historical status as a slave state was slow. Famously, the Kentucky state legislature did not ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until 1976. But slowly, the idea that slavery was a cruel institution began to trickle down to mainstream public history in Kentucky as it did in other places in the United States. This was due to the fact that the Civil Rights Movement had connected the contemporary struggles of African Americans with the oppression they had faced during slavery, Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era. Gradually, public sites and educational institutions around the state began to portray emancipation as a redemptive triumph and thus, the Great Emancipator became a more palatable figure in the South. It was in this interpretive environment that white Kentuckians finally began to lay claim to Abraham Lincoln and integrate him into a usable past for their state.

By 1975, Hodgenville established the Lincoln Days Celebration, “for the purpose of celebrating the birth of Abraham Lincoln in an appropriate manner, to create an awareness of his values and influences upon this nation, and further the cultural, economic and civic interests of LaRue County.” In 1977, Kentucky preservationists completed the restoration of Mary Todd Lincoln’s girlhood home in Lexington.

But Kentuckians did not appear to truly embrace Lincoln as their own until the early twenty-first century as the state began plans for celebrating the 200th anniversary of his birth. Along with historical organizations around the nation, various entities around the Bluegrass State developed plans for a two-year-long tribute to the revered president to take place between 2008 and February 2010. In 2004, the state created the Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) with the following goals: to “establish Kentucky as part of the Lincoln story on both a state and a national level by relating the critical role that Kentucky and Kentuckians played in his life and career.” And, of course, with financial interests in mind, the commission also wanted to use the bicentennial as an occasion to “enhance Kentucky’s heritage-tourism industry.”

Accordingly, schools, colleges, historical societies, public libraries, tourist sites, and other civic groups developed dozens of programs, events, and exhibits to mark Kentucky’s connection to Lincoln. The Kentucky General Assembly and the Transportation Cabinet created two new Lincoln road designations. US 31E became the “Lincoln Heritage Highway,” while the stretch of I-65 from Louisville to the Tennessee border was christened the “Lincoln Memorial Expressway.” They also commissioned signs declaring Kentucky the “Birthplace of Lincoln” at major border crossings into the state.

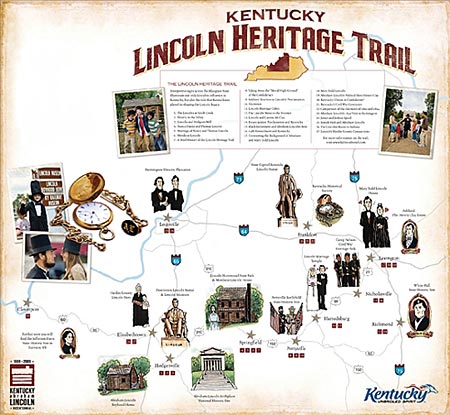

The state also developed the Kentucky Lincoln Heritage Trail, which included nearly twenty sites around Kentucky linked (some more closely than others) to Lincoln’s life and his Civil War legacy. Aside from obvious sites such as the Mary Todd Lincoln House and Lincoln’s Boyhood Home, these include locations such as the “Lincoln Marriage Temple,” which shelters the log cabin in which historians believe Nancy Hanks and Thomas Lincoln married, the home of Lincoln’s uncle Mordecai, and a replica of a cabin similar to the one once inhabited by his step-mother, Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln.

It seemed that although—and perhaps because—Lincoln resided for such a brief period of his young life in Kentucky, no connection to the president was too minor to include. A number of other sites earned their way onto the trail by their connection to the Civil War: the Camp Nelson Civil War Heritage Park, which marks the third largest African American recruitment camp in the nation, and the Perryville Battlefield Historical Site. Even Jefferson Davis’s monument and birthplace won a spot on the map.

In both style and substance, these events and places stressed Lincoln’s humble roots, his unlikely rise to the highest office in the land, and his lasting legacy in keeping the Union intact during the Civil War. Not surprisingly, the bicentennial effort highlighted his role in emancipating enslaved African Americans, the very act that made him so unpopular in his home state almost a century and a half before. In the post-Civil Rights era, white Kentuckians seemed ready to embrace Lincoln for the same reasons they had once maligned him.

The KALBC also outlined plans to “incorporate the relevance of the Lincoln story into educational programming across Kentucky.” The Kentucky Department of Education, Georgetown College, and the Kentucky Historical Society (KHS) worked together to develop lesson plans centering on Lincoln for elementary, middle, and high school students. The lessons tied Lincoln’s life and work to Kentucky’s teaching standards and brought Lincoln into the classroom in a number of different subject areas. The KHS also mounted an exhibit inside of a tractor-trailer that traveled to schools and public events all over the state.

In stark contrast to Kentucky’s effort to observe the 100th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth a century earlier, the connections between Lincoln, slavery, and emancipation were front and center between 2008 and 2010. The KALBC funded numerous projects that focused on African American experiences of the Civil War era, including the Underground Railroad, USCT recruitment and enlistment in Kentucky, and the experiences of black families in the state’s contraband camps. The commission also funded a workshop for museum docents and local historians entitled “Interpreting Slavery at Kentucky Historical Sites,” designed to advise “employees how to talk about slavery with the public.”

The Commission and Advisory Council members were a diverse group of Kentucky scholars and citizens, and included organizations such as the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission. Famed African American artist Ed Hamilton sculpted a new statue of Lincoln, which stands in Louisville’s Lincoln Park along the city’s waterfront. In the early twenty-first century, Kentucky African Americans played a large role in shaping the state’s memory of Lincoln, both figuratively and literally.

Meanwhile, in an interesting turn, Kentuckians mounted a much more limited celebration for Jefferson Davis, who had also been born in Kentucky in 1809. Vestiges of Confederate partisanship remained, however. In 2007, the State Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans protested that the Kentucky Lincoln Bicentennial Commission had circumvented proper procedures in order to have the Transportation Cabinet approve a Lincoln bicentennial license plate bearing the official Kentucky Lincoln Bicentennial emblem. While Kentucky SCV members, who were also seeking approval for their own specialty plate, denied that the tag’s honoree had anything to do with their outrage, they used the opportunity to call for the resignation of the co-chairs of the bicentennial celebration and the executive director of the Kentucky Historical Society.

As a result of the state’s bicentennial commemoration, citizens of Kentucky—young, old, black, or white—could not miss the state’s connection with the sixteenth president as well as the heroic light in which it cast his historical achievements. Certainly, it was not lost on Skyler Hornback, who, five years before he would go on to Jeopardy fame, was selected by officials at Abraham Lincoln Elementary to introduce First Lady Laura Bush when she visited Hodgenville as part of the bicentennial festivities in November 2008. “Here,” Bush told the crowd, “we remember that the man who became our beloved president was once just a young boy.”

The recent embrace of Lincoln is a part of the process by which Kentucky is slowly shedding its constructed Confederate identity in favor of one that acknowledges historical divisions among the state’s whites, as well as between whites and African Americans. Within this pluralistic history, Abraham Lincoln has finally become useful and duly celebrated in his native state.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Delta Women Writers for reading and offering insightful criticism on an earlier draft of this essay.

Further Reading

Readers can find further information about Abraham Lincoln’s portrayal in American history in Merrill Peterson’s Lincoln in American Memory (New York, 1995).

For more information on the tradition of anti-Lincoln sentiment in the U.S., see Don E. Fehrenbacher, “Anti-Lincoln Tradition,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 4:1 (1982) and John Barr, Loathing Lincoln: An American Tradition from the Civil War to the Present (Louisiana State University Press, forthcoming, 2014).

Despite being nearly 90 years old, Ida Tarbell’s In the Footsteps of the Lincolns (New York, 1924) offers a fascinating look at early Lincoln tourism in Kentucky. For a more modern take, see Andrew Ferguson, Land of Lincoln: Adventures in Abe’s America (New York, 2008).

For more on the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, see the National Park Service Website. A detailed report on Kentucky’s Bicentennial Commission is also available.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.2 (Winter, 2014).

Anne Marshall is associate professor of history at Mississippi State University. She is the author of Creating a Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State (2010).