Going Dutch

This curious comment appeared in 1810–in a review of “Parson” Mason Locke Weems’s cherry-tree biography of George Washington–but it might just as well have been written about Edmund Morris’s 1999 Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan, a book that historian Joyce Appleby labeled “literary Forrest Gumpery” and commentator George F. Will called weird and perverse.

Biographies make strange bedfellows. Or at least the controversies over them do. The fracas over Dutch united journalists and academics, liberals and conservatives, onetime Reagan staffers and longtime Reagan detractors. Most critics claimed that the flap revealed more about contemporary culture wars than about Ronald Reagan, but few observed that it marked a shift in how we think about biography itself.

The comparison with Weems seems apt: Morris, like Weems, stands accused of inventing fictions about a larger-than-life American president. Over the past century, “Parson Weems” has become synonymous with mythmaking, hero-worship, and bad history. Yet, for much of the nineteenth century, Weems’s name meant something different to American readers. His work provided patriotic inspiration to generations of young Americans. Abraham Lincoln read Weems’s Life of Washington as a boy and, as president-elect, cited it before the New Jersey state senate. Ellen Humphreys, the child protagonist in Susan Warner’s best-selling 1850 novel The Wide, Wide World, couldn’t put the book down. Yet Weems, like Morris, was embroiled in culture wars of his day. Understanding those battles, and Weems himself, may help explain why he and the cherry tree remain with us nearly two hundred years later–and why Dutch has raised so many hackles.

The Dutch reviews split over Reagan himself, of course. In the online magazine Slate and on radio and TV, conservative critic Dinesh D’Souza noted that Morris didn’t “credit Reagan’s force of intellect” or consider Reagan’s role in creating “the political and social framework for the silicon revolution,” among other omissions. In the Washington Post, the noted historian of early America Joseph Ellis emphasized the controversies–implicitly, the downsides–that Morris failed to appraise systematically: the tax cuts and defense spending that “produced those unprecedented deficits”; “his complicity in the arms-for-hostages deal labeled Iran-Contra.”

Critics focused mostly on Morris’s approach to biography: inventing fictional characters–including a version of himself–whose lives intersect with Reagan’s, inserting himself as biographer into the narrative. In this conceit, the teenaged Morris sees Reagan as a teenaged lifeguard; is it character Morris or biographer Morris who writes, “Watching him [swimming]–indeed, trying to imitate him–helped me understand at least partly the massive privacy of his personality” (61)? The critics’ complaints recurred across ideologies and occupations. Historians may have made more of Morris’s endnotes–which include correspondence from his fictional characters beside authentic documents–than did the journalists and pundits. But the larger critique was the same: Morris’s book was “a tragic ruin” (wrote editor Charles Krauthammer), even “dung biography” (political scientist Larry Sabato, who was connecting the controversies over Dutch and the Brooklyn Museum’s “Sensations” exhibit [Weeks, “Can Put It Down!” 1999]).

“Weems, like Morris, was embroiled in culture wars of his day.”

But look at where the critics placed deeper blame, and another story emerges. D’Souza argued that Morris reflected “the prejudices of the intelligentsia,” and that Dutch was “an attempt to avenge Reagan’s rout of the intellectual class.” George Will went further: “Down from the academy has trickled the poison of postmodernism,” in which “facts hardly matter, only interpretations are real.” Postmodern history “invests the historian with the heroism of an artist, creating reality rather than fulfilling the mundane role of describer and interpreter of reality.” (Never mind that romantic historians such as Francis Parkman and George Bancroft practiced history as heroic literary art a century and a half ago, before anyone coined the term “postmodernism.”)

From the academy came a different interpretation. Joyce Appleby admitted that “some would say that questions of truth, accuracy, and representations of realities have been rendered moot by postmodernists.” Appleby’s postmodernists, though, included “20th-century philosophes, literary scholars, science skeptics and social critics”–not historians. Indeed, the historians identified another source for Morris’s approach: up from popular culture, not down from the academy. Appleby included historical novels and movies and a “cultural milieu . . . imbued with factoids, infomercials and so on” in explaining Morris’s “latest hybrid–bio-fiction, imagino-realism, history lite.” Joseph Ellis linked Dutch to “docudramas” such as Oliver Stone’s JFK. In the historians’ eyes, Dutch wasn’t the logical result of current trends in academic history. It was what happens when a writer ignores the historian’s sine qua non: sticking to the evidence, at the possible cost of boring readers.

Historian Alan Brinkley reminded us that some recent historians have blended fact and fiction. He credited John Demos’s The Unredeemed Captive and Simon Schama’s Dead Certainties with doing so more successfully than Edmund Morris’s Dutch. Brinkley’s point is important: this wasn’t simply a debate between conservative pundits and the supposedly liberal intelligentsia who have re-created history writing. It was also a debate within the historical profession about how far it’s fair to imagine one’s way into the past.

Biography, however, isn’t just a branch of history. It has been a literary genre at least since Plutarch. When critics connected Dutch to James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, they placed Morris in literary company–even if, as Ellis noted, Morris’s Boswellian touches were only a literary conceit. For centuries, biographies have been criticized for blurring the line between truth and fiction. One reviewer in the 1850s lambasted James Parton, America’s first career biographer, for erring “on the side of conjecture” rather than spoiling “a good story.” When Harriet Beecher Stowe thanked Parton for making biographies “more interesting than romance,” she hoped parenthetically that “it is not by making them in part works of imagination.”

As Judith Shulevitz noted in Slate, the twentieth-century penchant for biographical leaps of imagination began with Lytton Strachey, biographer of Queen Victoria, who reacted against the fact-filled, ponderous “lives and times” of great men. The twentieth century’s innovations in biographical technique usually came in literary biographies. Authors and artists seemed to summon their biographers to imaginative acts of their own. Some of Dutch‘s critics speculate that Reagan–or the frustration of capturing his essence–cast a similar spell on Morris. Or perhaps Morris gave our first postmodern president, the man who blurred history and the movies, exactly the biography he deserved (Kakutani 1999; Vidal 1999).

For his part, Morris placed his work outside his critics’ worlds. He told the Washington Post‘s Linton Weeks that he was more interested in how “Gore Vidal, Richard Holmes, John Updike, people of that caliber” viewed his book than in the responses of academic historians, journalists, or pundits (Weeks, “How to Pen One for the Gipper,” 1999). In fact, before reading Dutch, Vidal wrote about it in the New York Times, humorously seconding Morris’s “fictionalizing himself”–since, after all, show business shaped Reagan’s entire ascent. Morris and his publishers envisioned a broad audience, with whom Dutch would pass what the author in 1991 called the “ultimate test of any piece of nonfiction writing”: “its success in saying something–or quoting something–that a majority of readers ‘can’t help but believe'” (Will 1999). Morris yoked two audiences, literary writers and the book-buying public, that supposedly transcended the political and cultural wars of the talk shows and the academy.

Parson Weems never tried to have it both ways. Like Morris, he may have invented his sources. Did “the aged lady, who was a distant relative” of George Washington, really exist? Or the “very aged gentleman, formerly a school-mate of his” (Cunliffe 1962, 9, 19)? Like Morris, Weems claimed unprecedented access: his title page announced him (falsely) as “rector of Mount Vernon parish.” Unlike Morris, however, Weems knew that his life of Washington would not satisfy critics of a literary bent.

To join America’s foremost promoters of patriotism, Mason Locke Weems (1759-1825) traveled far from his early education. Born to wealthy parents in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, Weems received an elite education in England–first medicine, then the ministry–while the Revolution raged in America. He was ordained by the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1784, just when many patriots in the newly independent United States came to shun Anglican ministers. (His ordination was permitted without the customary oath of allegiance to the crown, thanks to a 1784 parliamentary act dispensing “persons intending to serve in foreign lands” from taking the oath.) Weems returned to serve as a rector in several churches in Maryland. After he married Frances Ewell of Belle Air, Virginia, in 1795, he relocated to nearby Dumfries in Prince William County, on the Potomac eighteen miles below Mount Vernon.

Sometime before 1791, Weems started selling books for Philadelphia’s Mathew Carey and other publishers. This new career took him into towns and countryside from New York to Georgia, where he met the American common reader: the farmer or tradesman whose books might include little besides a Bible, a book of hymns or psalms, and the latest almanac. A full-time book peddler by 1793, Weems often preached in the towns where he brought his wares. Much of this preaching was melodramatic. So were the twenty-five-cent religious tracts he started writing and selling in the 1790s, the decade when revivalism took hold in America’s backcountry. Full of lurid tales of sin and excess, these included Hymen’s Recruiting Sergeant (1799), God’s Revenge Against Murder (1807), God’s Revenge Against Gambling (1810), The Drunkard’s Looking Glass (1812), God’s Revenge Against Adultery (1815), and The Bad Wife’s Looking Glass (1823). Weems the parson stood at the vanguard of a new evangelical culture and a newly democratic ethos. Weems the traveling salesman was also at the forefront of a new American capitalism. Ever the promoter of himself and his work, he exclaimed to Carey in 1807 that “I am sure–very sure–morally & positively sure that I have it in my power (from my universal acquaintance, Industry, & Health) to make you the most Thriving Book-seller in America. I can secure to you almost exclusively the whole of the business in the middle & western parts of all these Southern states from Maryland to Georgia inclusive” (Skeel 1929, 2:362).

“It is not then in the glare of public, but in the shade of private life, that we are to look for the man. Private life is always real life.”

When George Washington died on December 14, 1799, Weems had been working on a biography for six months. Just weeks later, he wrote to Carey, “Washington, you know is gone! Millions are gaping to read something about him. I am very nearly prim’d & cock’d for ’em” (Skeel 1929, 2:126). Weems’s first edition (not published by Carey, who soon regretted the mistake) ran just eighty pages. A memorial volume not unlike dozens of other tributes to Washington, Weems’s little book consoled Martha Washington on her loss of “that best of husbands.” It also used Washington’s death to plead for national unity during the 1800 presidential election between President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson–a contest that had really begun with Adams’s 1796 victory over Jefferson (Weems 1800, dedication page). Washington may have been the father of his country, but by the middle of his presidency partisan conflict roiled the nation, with Washington identified with the Federalists. Adams’s Federalist presidency was more bitter still, and the 1800 rematch produced charges of atheism and libertinism against Jefferson, and of monarchism against Adams.

In 1800, Weems envisioned his book as “a feast of true Washington Entertainment and Improvement, both to ourselves and our children.” By 1808, the book was in its sixth edition–now published by Carey. It had a new title, The Life of George Washington: With Curious Anecdotes, Equally Honorable to Himself, and Exemplary to His Young Countrymen. It contained many of the anecdotes that would become American legend: not just the cherry tree, but also the story of Mary Washington’s dream, in which little George’s mother dreams that her son extinguishes a rooftop fire on the family’s home (a homespun metaphor for the Revolution). For the first time, this edition identified Weems as “formerly rector of Mount-Vernon Parish.” In fact, he had preached for several months at Pohick Church in Washington’s family parish of Fairfax.

How did this celebration of Washington become fodder for the culture wars of the Jeffersonian era? In one letter to Carey, Weems called his little book “moralizing & Republican” (Skeel 129, 2:362). He meant that it wasn’t something else: Chief Justice John Marshall’s historical, five-volume, Federalist biography of Washington. Weems knew Marshall’s work well, because he was one of its traveling salesmen for the publisher C. P. Wayne. He also knew that Marshall’s work was a tough sell. It was expensive. Its volumes came out slowly: the first in 1804, the last not until 1807. Its fifth volume, on Washington’s presidency, was so contentiously Federalist that Jefferson considered writing a rebuttal. Marshall and the Federalists had made Washington one of their own. Weems told a different story: of a Washington above parties, a Washington whose successor could easily be the Republican Jefferson. In Chapter 13, “Character of Washington,” Weems contrasted Washington’s spotless character with the errant ways of four other men: Benedict Arnold, Charles Lee (the general who envied Washington), Alexander Hamilton, and Aaron Burr. The last two, of course, were Jefferson’s great antagonists, a fact that could not have been lost on contemporary readers (Onuf 1996, xvii-xviii).

At the same time, Weems’s Life of Washington participated in a conflict over biography itself. In the new United States, two concepts of biography vied for supremacy. One derived from England–specifically, from the literary essays of Samuel Johnson, the great English lexicographer. Johnson and his disciples argued that biography ought to reveal its subjects in their “domestic privacies”: how they appeared off the public stage. Their purpose was not to tear down the reputations of great men (and occasionally women), but to get behind the “vulgar greatness” of public appearance. Presenting the “invisible circumstances” of a subject’s life would offer readers “natural and moral knowledge” and enhanced “virtue.” Johnsonian theory, in other words, made biography into a branch of moral education.

So did the other concept of biography: a republican vision that other critics championed as uniquely American. If American republicanism focused on individuals’ role as citizens–and if biography ought to offer examples for the next generation to follow–should not republican biographies present America’s heroes astride the public stage? Most early American biographers believed so. Their subjects rarely appeared outside their places on the battlefield or in the councils of state. This concept of biography virtually ensured women’s absence: indeed, the classical republican notion of “virtue”–the word itself derived from vir, Latin for “man”–emphasized masculine civic virtue (even if a concept of republican womanhood also emerged after the Revolution). For the most part, Johnsonian ideas about biography appeared only in literary magazines, some of which took their cues from British quarterlies, while republican ideas dominated biographies themselves.

Weems declared in the introduction to his life of Washington, “It is not then in the glare of public, but in the shade of private life, that we are to look for the man. Private life is always real life. Behind the curtain, where the eyes of the million are not upon him, and where a man can have no motive but inclination, no excitement but honest nature, there he will always be sure to act himself; consequently, if he act greatly, he must be great indeed.” Nobody had ever told Washington’s private life before, Weems wrote. His story wouldn’t offer “domestic privacies” in the Johnsonian sense: it would not reveal the foibles that made Washington human and thus familiar to the ordinary reader. Instead, Weems’s story would display Washington’s glorious traits outside the political and military realms: “the dutiful son–the affectionate brother–the cheerful school-boy–the diligent surveyor–the neat draftsman–the laborious farmer–and widow’s husband–the orphan’s father–the poor man’s friend” (Cunliffe 1962, 1-3). Nevertheless, it would teach a rising generation of Americans the private virtues needed to sustain a democratic republic (though surely not to lead revolutions of their own).

The key distinction here was between private virtues and privacy. In the introduction, Weems wrote that he would not discuss details of Washington’s marriage or of Martha Washington’s life. It was “contrary to the rules of biography,” he explained, “to begin with the husband and end with the wife.” Weems meant that there were bounds of propriety that biographers were obliged to respect. These boundaries would keep women–the wives of male subjects–out of most biographies for the next fifty years. These were not the familiar republican boundaries, in which women vanished because they weren’t citizens in the classical sense. Instead, Weems helped lay the groundwork for the idea of “separate spheres,” in which domestic privacy would be a hallmark of a new middle class.

Mason Locke Weems hailed from the Maryland elite–perhaps even Tories, depending on which account one reads (Onuf 1996, xix). George Washington was a scion and leader of Virginia’s landed, slave owning gentry. Their bloodlines and birthrights suggested eighteenth-century men. Yet in his own professional life, Weems seemed to mark America’s future: evangelical, capitalistic, even hucksterish. In depicting Washington’s character, he helped delineate the virtues of the nineteenth-century middle class: duty, religion, benevolence, industry, patriotism. Even in whom he left out–Martha–he offered a glimpse into the future. And his books sold.

The literary elite generally scorned Weems’s Life of Washington. As would be the case with Edmund Morris’s Dutch nearly two centuries later, some reviewers probably had political objections: they wished for a more Federalist treatment. But also like the controversy of 1999, another issue was at stake: the line between fact and fiction. The problem here wasn’t postmodernism perverting history. Rather, fiction itself was suspect in the early republic. Would fanciful tales turn readers’ heads away from practical duty and virtue? Would fiction, particularly of the sentimental variety that allowed readers into the hearts and inner thoughts of (often female) protagonists, displace more useful reading? Or could trappings of fiction help sell messages of morality?

To Weems, the boundaries between genres were permeable. Different genres could be complementary, not contradictory. As his sensational sermon-tracts revealed, he never refrained from adding romance to enhance appeal. At least one reviewer appreciated Weems’s Life of Washington for its romantic dimensions: “the Writer makes us alternately weep and laugh. . . . There is a kind of poetic fire running through every sentence of this History, that irresistibly fixes the Attention, warms the Heart, and brings to the Eyes those delicious Waters which flow from Piety, Love, and Admiration” (Skeel 1929, 1:28-29). In 1809, Weems accepted Brigadier General Peter Horry’s invitation to write a biography of General Francis Marion, Horry’s commander in the Revolution. Horry had tried but failed to write the book himself, so he sent his reminiscences to Weems. The parson promised to “polish and colour it in a style that will, I hope, sometimes excite a smile, and sometimes call forth the tear.” When The Life of Francis Marion was done, Weems told Horry, “knowing the passion of the times for novels, I have endeavoured to throw your facts and ideas about Gen. Marion into the garb and dress of a military romance” (Skeel 1929, 1:100-01, 2:427).

“Would fanciful tales turn readers’ heads away from practical duty and virtue?”

To others, the boundaries mattered. Hence Dr. Bigelow complained in the Monthly Anthology, and Boston Review that he couldn’t decide whether Weems’s life of Washington was “a biography, or a novel, founded on fact” (Skeel 1929, 1:55). That last phrase referred to contemporary novelists’ professions that their stories had real-life bases: thus Susanna Rowson’s best-sellingCharlotte Temple was originally called Charlotte: A Tale of Truth. Peter Horry was indignant at Weems’s Life of Marion: “A history of realities turned into a romance! The idea alone, militates against the work. . . . Most certainly ’tis not my history, but your romance.” Except for Horry, who had a personal stake in Marion’s story, Weems’s critics tended to be the literati of northern cities and southern plantations. Virginia writer and jurist St. George Tucker wrote to his friend William Wirt, also a Virginia statesman, that he had barely been able to stomach Weems’s first paragraph–after which “I shut the book . . . and have no desire to see it again” (Kennedy, 1:352-353). New York’s Monthly Magazine and American Review called Weems’s original edition “eighty pages of as entertaining and edifying matter as can be found in the annals of fanaticism and absurdity” (Skeel 1929, 1:14).

But Weems was a traveling bookseller in America’s backcountry. Hawking books and preaching in western Pennsylvania or North Carolina, he did the closest thing in the new United States to book tours and appearances on “Larry King Live.” Weems’s customers were his audience, and he knew just what they wanted to read.

Parson Weems has had an afterlife that’s likely to outlast Dutch. In the nineteenth century, millions of Americans read his biographies of Washington and Marion (although his lives of Benjamin Franklin and William Penn probably sold less well)–even if critics and historians ridiculed them as didactic fiction. The story of Washington and the cherry tree became an American legend, not just repeated in images of Washington, but also invoked in political cartoons to poke fun at current political leaders. The twentieth century was less kind. The 1920s penchant for debunking historical icons produced W. E. Woodward’s George Washington, The Image and the Man (1926), whose title spoke volumes: the Weemsian image wasn’t the real man, whose faults ranged from vanity to horse racing and card playing. Weems himself became associated with sanitized, didactic pseudo-history–to put it more bluntly, mythmaking. Historians tended to dismiss him.

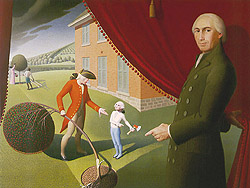

The Iowa artist Grant Wood offered a more humorous commentary. In his 1939 painting Parson Weems’ Fable (Amon Carter Museum, Houston), Weems stands in the foreground, lifting a curtain to reveal little George.

Complete with head from Gilbert Stuart’s portrait, George stands before his father and points to the hatchet in his left hand. The cherries dangling from the tree mimic the tassels on Weems’s red curtain. On the eve of World War II, Wood hoped to counter fascist propaganda with “the preservation of our folklore.” He also aimed to show how American myths differed from Nazi ones: Americans could recognize that their fables were simply stories, and story telling and humor themselves were American traditions. In other words, to borrow a phrase from that other 1939 American classic, The Wizard of Oz, Wood knew that there was a man behind the curtain.

In the background of Parson Weems’ Fable, two slaves labor at another tree–a fact not lost on seventh-grader Taylor Davis of Hidden Valley Middle School near San Diego. Davis’s 1998 poem, “Overlooking Mount Vernon: After Wood’s ‘Parson Weems’ Fable,'” appeared in the Oak Grove Review, an local annual anthology of student poetry:

The boy

with the gray hair

holding the axe

that cut down the cherry tree,

his father is happy,

for he didn’t tell a lie.

I am the man pulling back the curtain.

I know the situation.

Little George’s dad

shouldn’t worry about George.

He holds the lives of the slaves

in the back of the picture,

their fingers tired

from picking cherries all day.

Grant Wood isn’t the only American artist to take Weems as a subject. In 1975, the American composer Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) wrote the score forParson Weems and the Cherry Tree, a ballet suite commissioned by Erick Hawkins. Thomson drew on “songs, marches, and parlor pieces from the Federal period.” The ballet was a comic one, inspired perhaps by the bicentennial; its twelve sections included “The Parson Writes His Book,” “The Parson Instructs George,” and “Chopping the Tree.”

Today, the phrase “Parson Weems” evokes multiple responses. The most common, of course, is Parson Weems the unreliable storyteller, whose myths aimed to inculcate values but whose history was half-baked at best. Several commentators have noted how the false history undercut the moral message. Commenting on the biblical doctrine of bearing false witness on the eve of the Clinton impeachment hearings, a North Carolina minister noted that Weems’s story hadn’t done its job: it “has succeeded in making George Washington the sworn enemy of all young children,” but it “certainly has not made them more truthful. The funny part of it is that this story about the virtue of telling the truth is itself not true–Parson Weems or somebody made it up.” Maybe the message is utterly different, at least for a generation of capitalists. In the New York Times, Michael Lewis, author of the best-selling Liar’s Poker: Rising through the Wreckage on Wall Street, suggested that the “true significance” of the cherry-tree story is that “it pays to lie, if you have the knack for it. And if you lie as well as Weems you can make a lot of people happy, simply by telling them what they think they want to hear.”

At the same time, historians and literary critics have rediscovered Mason Locke Weems as a major American cultural figure. Historians of American publishing always knew Weems: his letters to Carey and other publishers, a treasure trove about early American bookselling, were published in 1929, and numerous historians of print culture have examined his bookselling career. What’s new is the sense that Weems possessed larger cultural significance. R. Laurence Moore writes that “Weems’s marriage of aggressive marketing with a moral mission was one important starting point of America’s nineteenth-century culture industry,” especially the selling of religion. Steven Watts identifies Weems as “a captain in the swelling moral militia of bourgeois culture in early-nineteenth-century America.” Jay Fliegelman sees the cherry-tree story (“Run to my arms, you dearest boy”) as part of America’s revolution against stern patriarchal authority, a parable for the nineteenth-century culture of family sentiment. Conversely, T. Hugh Crawford argues that Weems made Washington into a new patriarch to stem the tide of revolution. Weems’s Life of Washington shows up in college courses on early American literature and the history of the early republic, thanks to this new interest and especially to a 1996 scholarly paperback edition.

“In the nineteenth century, millions of Americans read his biographies of Washington and Marion–even if critics and historians ridiculed them as didactic fiction.”

Weems isn’t without his political uses, either. The cherry-tree story appears in the “Buchanan Brigade Library–Our American Heritage,” a web site created in tandem with Pat Buchanan’s 1996 presidential campaign. According to Buchanan, today’s schools poison children “against their Judeo-Christian heritage, against America’s heroes and against American history, against the values of faith and family and country.” His library–whose contents range from the Declaration of Independence to Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” to the West Point Cadet’s Prayer–aimed to level the playing field. The day after President Clinton admitted his liaison with Monica Lewinsky, conservative columnist Linda Chavez wrote a piece called “How America Lost Its Moral Compass.” Once upon a time, Chavez wrote, children learned the value of truth from the story of Washington and the cherry tree. “But then a few decades ago, Americans became too sophisticated for the likes of Parson Weems’ popular tale. After all, it wasn’t strictly speaking a true story about the nation’s first president, whose reputation was busily being deconstructed by a new breed of historians committed to exposing the atrocities of dead, white, European males.” Shades of the controversy over Morris’s Dutch–where, too, conservative critics worried about the aftershocks of academic history.

Of all the current manifestations, I think Weems would most appreciate the Weems-Botts Museum in Dumfries, Virginia. Weems bought the building in 1798, probably to use as his bookshop, depot, and overnight lodging. He sold it four years later. Today the museum houses exhibits and hosts events, including a 1999 cherry-pie eating contest judged by an actor dressed as Weems. It also charges $3.00 admission and maintains the “Peddling Parson Book and Gift Shoppe.” Weems’s marketing methods were his own itinerant peddling, his sermons, and the advertisements he placed in local papers. But were he alive today, Weems would surely do exactly what the Weems-Botts Museum did last year. Dressed in eighteenth-century garb, then-curator Jeanne Hochmuth showed the house and talked about Weems in local classrooms. She insisted we’ll never know whether his stories were true or not. And the museum doesn’t need a traveling salesman. It has a web site.

Whether Edmund Morris’s Dutch has the staying power of Mason Locke Weems’s cherry tree has yet to be determined. Either way, the complaint that biographers blur the line between fact and fiction is nothing new. Perhaps some of the motivations for that blurring are also the same. Weems sold books by telling the people “what they think they want to hear,” to borrow Michael Lewis’s phrase. Morris’s line sounds eerily similar: the acid test of nonfiction isn’t its literal truth, but “its success in saying something–or quoting something–that a majority of readers ‘can’t help but believe.'” Morris may not mean “marketability” when he says “success,” or perhaps his literary aspirations don’t allow him to admit the mercenary motives that Parson Weems never denied. What changes is the context and language of the debate. Two centuries ago, it was Federalists vs. Republicans, domestic privacies vs. public deeds, and history vs. romance. Today, it’s Reagan and the intelligentsia, postmodernism and docudrama, Oliver Stone and Forrest Gump.

Bibliographic Essay

Mason Locke Weems’s colorful prose–in his biographies, tracts, and letters–remains a delight to read and a marvelous window onto the early nineteenth century. His Life of George Washington appeared in dozens of nineteenth-century editions, originally as M. L. Weems, A History, of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits, of General George Washington (Georgetown, 1800). The sixth edition (Philadelphia, 1808) introduced many of the famous stories, including the cherry tree. The two important scholarly editions were edited by Marcus Cunliffe (Cambridge, Mass., 1962) and by Peter Onuf (Armonk, N.Y., and London, 1996). Onuf’s introduction places Weems’s Washington squarely within the Jeffersonian context and provides useful biographical information on Weems (see xvii-xx). The other essential primary text is Emily Ellsworth Ford Skeel, ed., Mason Locke Weems: His Works and Ways, 3 vols. (New York, 1929), which contains Weems’s extant correspondence, descriptive bibliography for all the editions of Weems’s works, and copious extracts from contemporary reviews including elusive newspaper squibs. St. George Tucker’s April 4, 1813 letter to William Wirt appeared in John P. Kennedy, Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt, Attorney General of the United States(Philadelphia, 1849).

Recent scholarship on Weems is voluminous, as the peddling parson has become a cultural icon of the early republic. I’ve referred here to R. Laurence Moore, Selling God: American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture (New York and Oxford, 1994), 20-24; Steven Watts, The Republic Reborn: War and the Making of Liberal America, 1790-1820 (Baltimore and London, 1987), 142-144; Jay Fliegelman, Prodigals and Pilgrims: The American Revolution Against Patriarchal Authority, 1750-1800 (Cambridge, 1982), 201; T. Hugh Crawford, “Images of Authority, Strategies of Control: Cooper, Weems, and George Washington, “South Central Review 11 (Spring 1994), 61-74. Lewis G. Leary’s biography, The Book-Peddling Parson: An Account of the Life and Works of Mason Locke Weems, Patriot, Pitchman, Author, and Purveyor of Morality to the Citizenry of the Early United States of America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1984), is also helpful; and Catherine Clinton, “Wallowing in a Swamp of Sin: Parson Weems, Sex and Murder in Early South Carolina,” in The Devil’s Lane: Sex and Race in the Early South, ed. Catherine Clinton and Michele Gillespie (New York and London, 1997), 24-36, provides useful information on Weems’s sermon-tracts. My own book, Constructing American Lives: Biography and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1999), explains the early-republican debate over biography at greater length and discusses Weems extensively. The quotations about James Parton and biographical truth appeared originally in “Aaron Burr,” Southern Literary Messenger 26 (May 1858), 322-323; Harriet Beecher Stowe to James Parton, n.d., James Parton Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University. For an article geared toward a more popular audience, see Will Molineux, “The Cherry Tree, the Silver Dollar, and Parson Weems: Blessed by Imagination, a Preacher Takes for his Text the Parables of George Washington,” Colonial Williamsburg 22 (Spring 2000) 36-43.

Weems’s letters to Mathew Carey and other publishers, which appear in Skeel’s Mason Locke Weems: His Works and Ways, reveal much about print culture in the era before mass production and distribution. Secondary scholarship draws heavily on this correspondence: see James N. Green, “‘The Cowl Knows Best What Will Suit in Virginia’: Parson Weems on Southern Readers,”Printing History 17 (1995): 26-34; James Gilreath, “Mason Weems, Mathew Carey, and the Southern Booktrade, 1794-1810,” Publishing History 10 (1981): 27-49; Ronald J. Zboray, “The Book Peddler and Literary Dissemination: The Case of Parson Weems,” Publishing History [Great Britain] 25 (1989): 27-44; Jason Epstein, “The Rattle of Pebbles,” New York Review of Books 47 (April 27, 2000), 59.

For earlier twentieth-century material on Weems and Washington’s reputation, see Robert Partin, “The Changing Images of George Washington from Weems to Freeman,” Social Studies 56 (February 1965): 52-59. On Grant Wood’s painting, see Cecile Whiting, “American Heroes and Invading Barbarians: The Regionalist Response to Fascism,” in Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies, vol. 13, ed. Jack Salzman (Cambridge, 1988): 295-324. On Virgil Thomson’s ballet score, see Anthony Tommasini, Virgil Thompson: Composer on the Aisle (New York and London, 1997), 513.

I refer to these Weems-related web sites. Taylor Davis, “Overlooking Mount Vernon: After Wood’s ‘Parson Weems’ Fable,” Oak Grove Review (1998); David E. Leininger, “The Ten Commandments. #9 – No False Witness” (sermon delivered at St. Paul Presbyterian Church, Greensboro, N.C., November 22, 1998);“Buchanan Brigade Library–Our American Heritage” (1996); Linda Chavez, “How America Lost Its Moral Compass,” Jewish World Review, August 18, 1998; and the Weems-Botts Museum, which includes links to a biographical page on Weems, activities at the museum, and the Peddling Parson shop. Weems-related newspaper articles discussed include Ann O’Hanlon, “He’s the Cherry of a Curator’s Eye: George Washington’s First Biographer Gets a Place in History at a Tiny Museum,” Washington Post, February 19, 1996, p. E1; Michael Lewis, “The Capitalist: The Lying Game,” New York Times, April 23, 1995, sec. 6, p. 24.

Edmund Morris’s book is Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan (New York, 1999). It generated widespread commentary as soon as Morris’s approach became known–even before the book appeared. I quote from the following: Joyce Appleby, “Biography Lite: It’s Tasty, But Check the Label,” Washington Post, September 26, 1999, p. B1; Alan Brinkley, “Good Writing Gone Bad,” Slate, October 4, 1999; Dinesh D’Souza, “Last Gasp of the Intelligentsia,” Slate, October 4, 1999; Joseph J. Ellis, “Role of a Lifetime,”Washington Post, October 3, 1999, p. X01; Michiko Kakutani, “A Biographer Who Claims A License To Blur Reality,” New York Times, October 2, 1999, p. A15; Charles Krauthammer, “Edmund Morris’s Whydunit,” Washington Post, October 1, 1999, p. A33; Judith Shulevitz, “Who Framed Ronald Reagan,” Slate, September 29, 1999; Gore Vidal, “A Biographer Who Writes Himself Into the Picture,” New York Times, September 26, 1999, p. A17; Linton Weeks, “How to Pen One For the Gipper: Reagan Biographer Edmund Morris Defends His ‘Dutch’ Treatment,” Washington Post, September 30, 1999, p. C1; Linton Weeks, “Can Put it Down! ‘Dutch’ Generates A Blizzard of Buzz,” Washington Post, October 4, 1999, p. C1; George F. Will, “A Dishonorable Work,” Washington Post, September 29, 1999, p. A29.

This article originally appeared in issue 1.1 (September, 2000).

Scott E. Casper, Associate Professor of History at the University of Nevada, Reno, is the author of Constructing American Lives: Biography and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, 1999). He’s currently working on books about George Washington’s family in American culture and about the ways Americans imagined their First Families before radio and television.