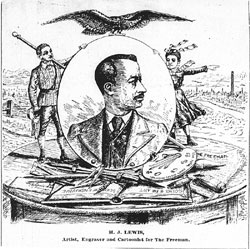

H. J. Lewis, Free man and Freeman artist

The first African American political cartoonist

What would it be like to start off in life as a severely handicapped slave? Not a very auspicious beginning, to say the least, but H. J. Lewis overcame it and became the first African American political cartoonist.

His early years are obscure, and it is difficult to define even general contexts, due to uncertainties about dates and to some extent about places. Henry Jackson Lewis was born in or near Water Valley, the seat of Yalobusha County in north-central Mississippi, about twenty miles south of Oxford. The year of Lewis’s birth is uncertain. Some sources say 1837, but one of his sons, Chester A. Lewis, said 1838. Other sources suggest later birth years, some as late as the 1850s.

The general setting of Lewis’s upbringing was not the stereotypical plantation of the “Delta Blues” lowlands of northwestern Mississippi but was about thirty miles east of the Delta margin, in rolling, low-hilly country. While still a small child, he fell into a fire, blinding his left eye and crippling his left hand. He “never had a day’s schooling in his life, but . . . educated himself,” according to an 1883 article in the New York periodical Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, which blithely characterized him as “a remarkably bright colored man.” But we know little more about his early life or young adulthood.

We also have no information at all on H. J. Lewis’s situation during the Civil War or the early postwar years and Reconstruction. We do not even know whether he still lived in Mississippi. If he did spend the war years there, they might well have been relatively quiet for him. There were no important battles in the Yalobusha County vicinity, which was remote from major strategic locations such as Memphis and Vicksburg.

We next pick up the Lewis trail in February 1872, when records show that a Henry Lewis bought a house in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. The Pine Bluff city directory for 1876-77 lists a “Lewis, Henry J., colored, laborer” living in that location, and the 1880 census includes an “H. J. Lewis” household there, including his wife (Lavinia Dixon Lewis) and their first three children (John, Richard, and Lillian). His age is listed as “40,” which would imply a birth year of 1839 or 1840.

Lewis probably did not earn his living primarily as an artist during the 1870s. We have no record of any of his drawings before 1879. In January, March, and August of that year, six engravings made by Harper’s Weekly staff artists and credited to “sketches by H. J. Lewis” showed scenes and situations along the Arkansas River in the Pine Bluff region. Then there is another frustrating gap: we have no further published Lewis drawings or derivative engravings until early 1883. But we do know that his fourth child and second daughter, Elizabeth, was born in Pine Bluff around 1881.

Lewis must have remained active artistically, at least locally and probably regionally. In its October 25, 1882, issue, the Pine Bluff Commercial, a white newspaper (still in existence), in a series of one-paragraph entries under the heading “Additional Local News,” stated, “J. H. [ sic ] Lewis, the caricaturist and pencil artist is still aboard in Pine Bluff. His sketches of both imaginary and real scenes, are wonderfully correct and we bespeak for him a brilliant and successful future in his line of business.” This prediction, and the characterization of the artist as a “caricaturist,” foreshadowed Lewis’s ultimate career.

But very shortly after the article appeared, Lewis took on a new and unexpected line of artistic work, making pencil drawings of prehistoric Indian mounds and their surroundings for the Smithsonian Institution. In early November 1882, he was hired by Dr. Edward Palmer, a pioneering and prolific field worker and specimen collector in “natural history” and archeology, who had been working about a year on the Smithsonian’s great “Mound Survey.” That project covered much of the eastern United States and ultimately disproved the racist theory that the mounds had been built by a “lost race” of non-Indian “Mound Builders.”

It is not clear how Lewis came to work for Palmer, but the latter had been working at a hectic pace in northeast Arkansas and had traveled by train and boat from Forrest City eastward to Memphis. Lewis’s first mound drawings were made in early November, either in the southern part of Memphis or along the Mississippi River to the north on the Arkansas side, so they may have met on the waterfront in Memphis. Perhaps Lewis had traveled by steamboat and set up his easel there to sketch river life and make caricatures for passersby. Palmer himself was not a good artist, yet had been charged with bringing back drawings of the mounds. In Lewis, he found just the person to make such drawings.

Lewis may well have influenced the coverage of the survey, for within a few days after he joined Palmer, they traveled by train from West Memphis to Little Rock and thence almost immediately to Pine Bluff, which was used as a base for forays to mound sites in the southeast Arkansas interior. Lewis worked with Palmer from that time until March 1883, producing at least thirty-four pencil drawings (including a few valuable maps) of mound scenes in Arkansas, plus one in Tennessee, two in Mississippi, and three in Louisiana.

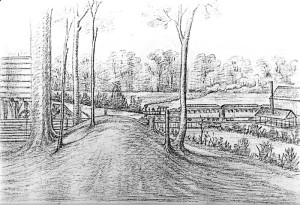

Engravings made from a number of Lewis’s drawings by Smithsonian artist-archeologist William Henry Holmes were published in the 1894 final report on the Mound Survey project, but Lewis was not acknowledged. For nearly a century, Lewis’s originals were more or less unseen but were well curated in the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives. A few of them were published by archeologists in the 1970s and 1980s, but his works were not fully published and properly credited until 1990 (fig. 1).

Several engravings derived from Lewis’s Mound Survey work (some showing flood scenes rather than mounds, or mounds as islands surrounded by floodwaters) were published in April and May 1883 in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. But Leslie’s engravers grossly exaggerated mound heights and the sizes and decorations of artifacts such as pottery vessels. In late May 1883, Leslie’s published one more engraving derived from a nonarcheological Lewis sketch, showing an Arkansas River ferry near Pine Bluff, perhaps indicating that the artist had returned home. His fifth child and third son, Chester, had been born in January of that year.

The next five years are, once again, lost ones as far as the artistic evidence is concerned. We have not found any further Lewis-derived engravings in Harper’s or Leslie’s from these years, nor anything at all in issues of Puck and Judge, two pictorial humor weeklies to which several sources say he contributed. If one April 1891 obituary’s statement that Lewis moved to Indianapolis “two and a half years ago” is correct, he must have made the move in late 1888, but we have no evidence of his presence there until the publication of a February 2, 1889, cartoon.

Our only real clues to Lewis’s whereabouts and activities during those “lost years” are the births of his two youngest children, Henry W. and Francis Louise, in Pine Bluff around 1885 and 1887 and a brief interview with him published in the November 24, 1889, issue of the Indianapolis Journal, a white newspaper. In the interview he reported that “only four years ago” he ran out of work in Pine Bluff and went (about fifty miles) to Little Rock, where he was hired as a “porter” by the Arkansas Gazette, one of the oldest newspapers west of the Mississippi. While there, he watched some white engravers and learned something of their trade.

Meanwhile, in mid-1888, an energetic virtuoso of Victorian eloquence, Edward Elder Cooper, founded an Indianapolis-based weekly black newspaper called The Freeman. Some sources have credited Lewis with being a “co-founder,” but this seems unlikely. Neither his name nor his cartoons are to be found in the seventeen surviving 1888 issues of the paper. Moreover, a white newspaper’s April 10, 1891, obituary stated that “Mr. Lewis was brought here a couple of years ago from Arkansas by Mr. Cooper.”

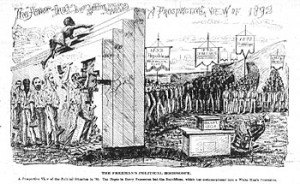

The Freeman’sinception more or less coincided with Cooper’s participation in a “black bolt” from the Republican Party and a black endorsement of the Democratic incumbent, President Grover Cleveland. “Not a colored man from Indiana had a voice in the last National Republican Convention,” said Cooper in an early issue of the Freeman. Shortly afterward, he proclaimed that the Republican Party had “willfully abandoned its first principles for the gold and silver of the country; best known as trusts, monopoly, syndicates and combinations . . . A few men, like hungry vampires are sucking the life blood from the honest labor of the country.” Cooper endorsed the Democratic slate for all offices on the national, state, and local levels.

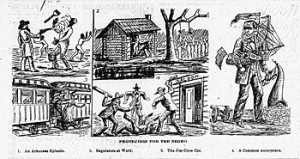

When Republican Benjamin Harrison was elected president, Cooper responded by transforming the rather conservative-looking, sparsely-illustrated Freeman into a “National Illustrated Colored Newspaper,” which he billed as “the Harper’s Weekly of the Colored Race.” He used the new national paper as a platform for his intensifying attack on the turncoat Republicans. The January 5, 1889, issue featured a new engraved masthead laden with symbolic illustrations, including Abraham Lincoln loosening the shackles of a slave. The issue also included a cartoon by someone named Beck, showing an “intelligent colored man” being refused admission to a theater, while a “seedy Irishman” was welcomed. This cartoon was more social than political, so Lewis’s status as the first explicitly and predominantly political black cartoonist remains intact.

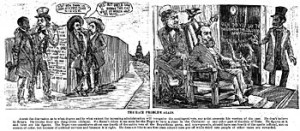

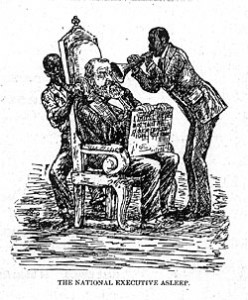

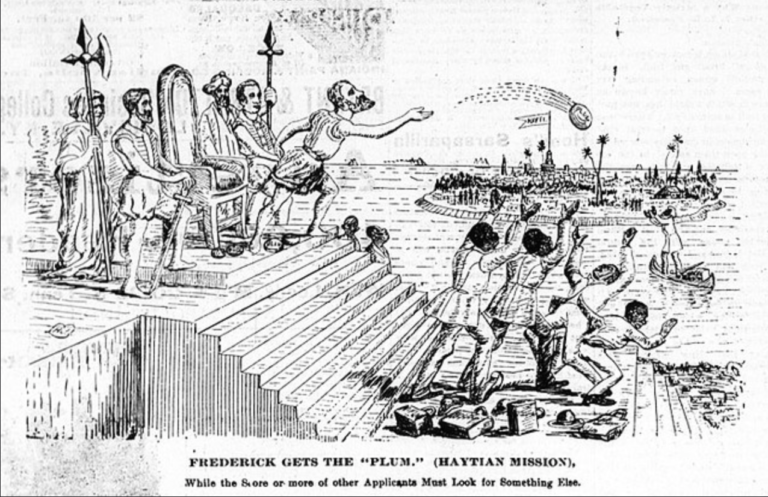

The next surviving issue of the Freeman, for February 2, 1889, includes Lewis’s earliest known work for the paper: a two-panel cartoon entitled “The Race Problem Again” (fig. 2). The cartoon addressed the recurring issue of federal appointments for blacks and introduced figures that became essentially “stock characters” in Lewis’s later work. One was Uncle Sam, generally represented as benevolently inclined toward blacks and a sort of conscience for white leaders. Another was Benjamin Harrison himself, depicted upon a throne-like chair and having the power and obligation to help blacks but somehow lacking the motivation or fortitude to act. More ominously, a southern planter type exerts his baleful influence upon the president. Along with these figures, Lewis included a black cherub, pointing to a wall clock whose hands approached twelve o’clock. Referring to the clock, the cherub says, “Ben did you say [’tis?] too soon for the colored man?—This is the hour—the XIth NOW.”

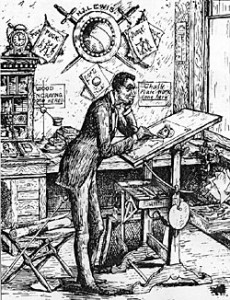

The cartoon’s crude and sometimes reversed or inverted lettering suggests that Lewis was still learning the art of woodblock engraving. But his style and lettering would rapidly improve thanks to a new, and for Lewis, more congenial reproductive technique. In a later editorial, Cooper proudly mentioned the paper’s “chalk plates made in two hours by the best Afro-American artist in the country,” and a self-caricature of Lewis at his drawing board (now in the collection of the Du Sable Museum of African American History in Chicago) included a sign reading, “Chalk Plates done here” (fig. 3).