Hard Times: The exhibition

“Bubbles, Panics, & Crashes: A Century of Financial Crises,” Baker Library Historical Collections. November 10, 2009-May 3, 2010, Harvard Business School, Baker Library. Curator: Dr. Caitlin E. Anderson.

The beautifully designed exhibition “Bubbles, Panics, & Crashes,” currently to be seen at Harvard Business School’s Baker Library, aims to enhance our modern-day conversation about financial crises with an assemblage of items from the library’s historical collections. The exhibition both resonates with today’s headlines while reminding us, as well, of oft-ignored experiences from the past. At the heart of a campus training the next generation’s top business executives, this space—which is usually devoted to more upbeat themes—has been given over to the darker aspects of the modern economy. Structured around four historical panics (1837, 1873, 1907, and 1929), the show covers a century of economic trauma. Without a heavy-handed interpretive framework, it nonetheless provides fascinating glimpses into the workings of American business and identifies a confluence of factors that caused each recurring collapse, among them asset overvaluation, negligent banking practices, erratic government policy, and the ebbs and flows of global capital and trade.

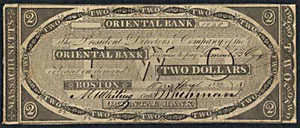

Even avid students of American history will learn new things from the exhibition’s focus on not just the central drama of these crises, but on various overshadowed affairs and subplots. The panic of 1837 is most often presented in the context of Andrew Jackson’s Bank Wars, and visitors will accordingly enjoy a display of the plethora of privately issued bank notes whose reckless proliferation, according to some accounts, precipitated the crisis. At the same time, the exhibition includes a section on the lesser-known failure of two of New England’s most eminently conservative banking institutions, a result of their misguided investments in Maine timber lands in search of better returns. The curators also attend to the collapse of numerous merchant houses around the world that was the result of the panic. We thus learn about the global reach of American commerce by reading a transoceanic correspondence between Boston merchant John Perkins Cushing to his partner, the Chinese merchant Houqua, observing that the “immense speculation in wild lands” in the American West meant “every description of property has fallen in a most alarming degree.” The partnership dissolved when Cushing shifted his resources and energy to financing railroads, a logic which guided many who were similarly prompted by the crisis to channel their money away from maritime trade and toward industrial investments.

Most textbooks cite the failure of Jay Cooke’s banking house in New York as having triggered the crisis of 1873. But “Bubbles, Panics, & Crashes” widens our perspective beyond the immediate national context by shedding light on the destabilizing role of European investment in American railroad securities. In this light, the United States appears as less of an industrial power in its own right and becomes something of a developing nation, flooded by foreign capital during a European credit bubble, and then left teetering when the money supply swiftly contracted. Thus, alongside images of the Northern Pacific Railroad cutting through vast, sparsely settled territories, the exhibition traces the web of capital to Germany, whose leading financiers helped underwrite that railroad’s construction. The hand-drafted contracts establishing Cooke’s business presence in London (a common practice for all major American financiers), and forming an all-star financial syndicate of American and English banking houses (including Cook, Morgan, Barring, and Rothschild), again highlight the global scope of business in those decades.

The sections on the later panics continue to treat the vagaries of modern business practices. Financial innovation, “much of it unregulated and poorly understood” (the curators thus echoing recent punditry), was deeply implicated in the panic of 1907. In the years leading up to the crash, life insurance executives had an almost free hand in investing some $20 billion of their policyholders’ savings. While enjoying lavish society balls that made a mockery of their presumed stewardship role for “orphans and widows,” industry leaders kept lax accounts, traded their clients’ money with little or no supervision, and were even known to purchase securities from syndicates in which they had a vested interest. Trust companies, which used aggressive investment strategies to produce high yields for much wealthier customers, were also caught “overextended” when crisis hit in October 1907, leading, most notably, to the failure of New York’s Knickerbocker Trust and the suicide of its president, Charles T. Barney. Whereas the crash of the New York Stock Exchange remains the emblematic event of 1929, the exhibition redirects our attention to smaller, regional stock exchanges, such as Boston’s, which thrived in a nonexistent regulatory environment. The urban real-estate bubble of the 1920s in cities like New York and Miami, whose foreclosures began to mount in 1926 and peaked in 1933, also receives its due attention.

If nineteenth-century crashes traditionally examined within national and local frameworks are treated here with an enhanced emphasis on their global dimensions, the approach is reversed when we move into the twentieth century. Worldwide crises like the Great Depression are perhaps counter-intuitively traced back to local causes: real-estate ventures and regional stock exchanges. The point, in both cases, is the same, namely, that the interconnectedness of the economy meant that no crisis was a contained incident. They all transcended geographical boundaries and cut across industries and economic sectors. World-encompassing flows of investment could cause devastation on the local level, just as “overvalued” real estate in particular locales could trigger instability that reverberated all over the globe. Indeed, economic panics are telling historical moments that reveal the structural complexities of the interdynamics between the global and local. The exhibition points to their usefulness for scholars who aim to broaden the frameworks of their analysis beyond the nation state.

More generally, the exhibition is most striking for how it sheds light on business “as usual.” Crises bring the architecture of the world economy into sharp relief and often signal important turning points. In this sense, massive collapses are to be found on the same continuum as the smaller ones that occur daily under the “perennial gale of creative destruction,” to use Joseph Schumpeter’s all-too-familiar phrase. The show is less illuminating when it recaps conventional wisdom about the roots of these crises, casting them as diverging from the otherwise rational workings of a stable market environment. The scholarly literature on the question leads to what seems to be an analytical dead end, alternating between the immutable (“financial crises have happened before, and … will happen again”) and the entirely contingent (“historically specific accidents under irreproducible conditions” [my emphasis]). This interpretive impasse might account for the exhibition’s many references to avarice, ignorance, and duplicity, which in themselves offer little in the way of a fully historicized explanation.

The reliance on psychological or deviant factors to explain economic crises taps into a venerable trope that is as old as the boom-bust cycle itself and is inscribed in the very terms “panic,” “speculative bubble,” and, more recently, “irrational exuberance.” The notion that human passions distort rational market behavior has only recently gained traction in the discipline of economics itself, but, as we can see in perhaps the most interesting aspect of this exhibition, it follows in the footsteps of a long line of institutions and individuals who sought to protect the market from the ruinous effects of crowd psychology. “Bubbles, Panics, & Crashes” nods to this tradition when it refers in positive fashion to institutions such as Boston’s Suffolk System, an antebellum regional central banking arrangement that “curbed the excesses of the rural banks” of Massachusetts, or Lewis Tappan’s Mercantile Agency, which in the wake of the 1837 panic began to offer credit information as an effort to systematize lending practices. It features Elizur Wright’s life insurance tables, based on mortality data, that aimed to scientifically manage the industry’s risk, and Harvard Professor James M. Landis, whose work inspired SEC financial regulation. There are many more who deserve a place in this important tradition, including the president of the Second Bank of the U.S., Nicholas Biddle, mugwump reformers Henry V. Poor and Charles Francis Adams Jr., banker J.P. Morgan and President Theodore Roosevelt, and continuing on up to today’s chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke.

Symptomatically, the involvement of Wall Street’s most respected firms in the events of the past few years—and in every historical crisis included in this exhibition—shows that ostensibly conservative private actors can hardly claim to have had a stabilizing role in the marketplace. These institutions always had access to the best information and mathematical models, so there is little reason to believe that better science would have made a difference. Even in the case of publicly appointed regulators such as former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, who at a recent hearing seemed to be at a loss for words in explaining the crisis, pinning it on a “once-in-a-century credit tsunami,” the cure can sometimes be as bad as the disease. Government oversight could be effective, to a degree, and a welcomed necessity. However, the longing for an authority capable of policing that ever elusive boundary between irresponsible speculation and legitimate business tactics will remain painfully unrequited.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.3 (April, 2010).

Noam Maggor is a Ph.D. candidate in History of American Civilization at Harvard University. He studies the history of American capitalism, and is currently writing a dissertation on urban governance in the late nineteenth century, with a particular focus on the lower middle class.