History in the Workshop

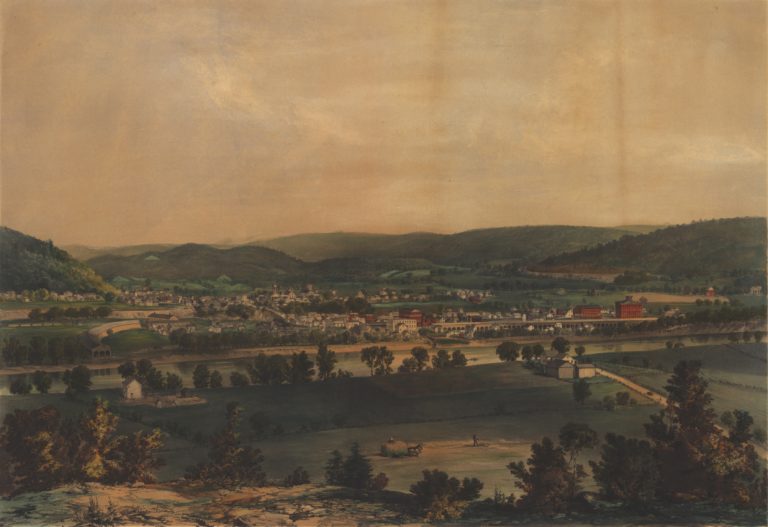

I have been working wood for as long as I can remember, although my earliest experiences on a small farm where I grew up were mostly of the crude carpentry sort. Rehabilitating and restoring three houses—one an 1885 Eastlake-style house designed by the first woman architect in Rochester, New York; the second an Andrew Jackson Downing Italianate pile in the countryside east of that city; and the third an amateurish “handmade” and somewhat crazy contraption in the New Hampshire woods—further sharpened my skills.

Eventually I had the good fortune to direct an exhibition design-and-construction operation in a medium-sized history museum in Rochester, an area rich in highly skilled graduates of the School for American Craftsmen at Rochester Institute of Technology and of Alfred University, which is also renowned for its school of the arts. Their talents and their willingness to share their knowledge and skills inspired me to think more broadly about my own experience with wood. After I moved to my present position at Northeastern University, I came to know many superb woodworkers who were members of the New Hampshire Furniture Masters and the Guild of New Hampshire Woodworkers.

When my editor at Viking suggested a book on wood’s place in history, culture, and consciousness, I jumped at the chance. Acquiring new and better skills—and new and better machines and tools—had prepared me to write Wood: Craft, Culture, History. In retrospect this was a surprising move, since I am not by nature fond of risk. And this is certainly a risky book.

Part of the risk involved is revealed by the difficulty in categorizing such a book. Academic historians and even my publisher don’t quite know where to place it on the shelves. Should it reside with books about materials, material culture, crafts, or history? Viking/Penguin lists it under “History of Technology.” Bookstores usually place it with “Crafts” and occasionally in the “History” section. It is certainly informed by cultural history and the history of technology, but it is also guided by works investigating workmanship and design (David Pye’s The Nature and Art of Workmanship [1968], Sōetsu Yanagi’s The Unknown Craftsman [1972]), architectural history (Christian Norberg-Schultz’s Existence, Space and Architecture[1971] and Nightlands [1996]), and phenomenology (Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space [1964]). This book also called for research and writing about botany and the physics of woods, though I cannot claim expertise in either botany or materials science. I do know that these attempts to understand wood have helped me in my own workshop, where I would like to think I now make fewer errors. To take one example, I now plan for wood’s expansion and contraction in the hidden joinery of my work, rather than trying to force the wood to remain static.

Writing this book also altered my work process at the bench. I have found that as much as I organize my notes and plan my arguments, there are moments as I write when a new idea or explanation simply appears. The woodworking equivalent to this is the solution to a design, shaping, or joining challenge that similarly presents itself. Whether writing a page or making a piece, these answers are no less valuable, whatever their source. Writing has taught me to let my elaborate plans and calculations ease their grip and let the tools flow. This is, however, not as easy as it sounds.

Contending with the physical characteristics of various woods and the way they respond to machines and the hand has also helped clarify how I think about history. Wood is infinitely variable and often unpredictable in the way it responds to being worked or to its environment. Good machines help us shape it with precision, but that exactitude can be ephemeral. Cutting and reshaping can relieve unseen physical stresses or tension deep inside the board or beam, turning our machined precision to mere approximation from one day to the next. This inconstancy seems to me analogous to the unpredictability, irrationality, and sheer orneriness that characterized human behavior in the past, and the historian’s paradigms, models, and methods analogous to the machines in the workshop. I suppose that explains why I am more comfortable with the humanistic side of history and with the intellectual and cultural history of my mentors, chiefly Warren Susman and Hayden White. The former directed my dissertation at Rutgers; the latter introduced me to history at the University of Rochester.

This project also had the largely unintended consequence of pushing my consideration of history in two seemingly opposite directions. On one hand, studying the history of a material that grows on or once grew on most of the world’s land mass logically meant that I had to examine wood in cultures other than that of the region I have studied for most my career—the United States. When I considered places of worship, I was drawn to what I think are the most inspiring wooden structures of religion—the stave churches of Norway and the elaborately carved marai of the Maori. My examination of wooden watercraft includes not only dugouts and bark canoes from Native Americans but also dhows, junks, and the behemoths of the “Age of Sail,” when wooden ships carried people and wooden barrels that held supplies, without which no boat could have ventured far from shore. Willow cricket bats, yew bows, and hickory-shafted golf clubs were transnational gear; some have been superseded by alloys and plastics, but some sporting equipment—such as the Irish hurley—is still made of purpose-grown native ash. I don’t know whether this book is world history or not, since that paradigm seems to me to be continually shifting. I am more comfortable thinking of it simply as cultural history.

As I cast a wider geographic and cultural net, I also began to consider more carefully the micro-view of woodworking, in particular, the history of individual artisans. Woodworking encompasses a multitude of specialized trades—coopers, wheelwrights, shipwrights, cabinetmakers, carpenters, carvers, and joiners, to name a few—and my reading and experience in the workshop turned me to examining these artisans and to thinking about their places in global history. In the aggregate, skilled woodworkers are often seen by both historians and the general public as possessing some sort of magical or mystical relationship to the material and the craft. While this might seem complimentary or positive, it in fact diminishes the artisan’s years or work, discipline, intellectual synthesis, design knowledge, and problem solving.

Studying the history of this essential material has made it clear that while wood provides the opportunity for using renewable resources, we do not seem to understand what this entails. Sustainable and managed forestry are not new concepts. In Japan and some of the German states, attempts to reforest began in the sixteenth century. For generations there have been purpose-managed forests of oak and sycamore (for the wine-barrel and stringed-instrument trades) in other parts of Europe, as well as more recent softwood tree farming in the United States and Canada for the paper and construction industries. These are exceptions to common practice. The British mowed down their oak forests to build ships and could not convince landowners to plant more trees that would take a century or more to mature. Giant redwoods and sequoias in the American West were felled as if they would magically return in less than five hundred years. The rainforests are burning as you read this. In the end, these purposes—closer consideration and appreciation of the actual work and skill of woodworking and a sense of history and urgency about what the geographer Michael Williams has called “the deforestation of the earth”—are, I hope, the chief contributions of Wood. I now try to use lumber from forests certified as harvested in an environmentally responsible manner, I save more of what I used to think of as “waste,” recycle what I can, and use wood with what once were thought of as blemishes, such as small knots and odd or unexpected colors.

Designing and building things crude and refined forced me to think about the problems, failures, and solutions that I encounter every day in the workshop. Working through a building project requires careful planning and an ordered sequence of tasks, whether that project is as small as a side table or as large as redoing a bizarrely angled room with nothing level or plumb and no right angles. It is an intellectual layering process, sometimes with only minimal chances to correct errors made early in the project. The same general method seems to me to apply to researching, conceptualizing, and writing history—the process is complex, layered, and often difficult to repair, especially those errors made at the outset.

I suspect that my learning from failure in woodworking (more than from success) has helped me slow down my work process in general. I no longer try to start new tasks late in the day or rush something to the finish when I am close to the end, since I have found that this is when most of my errors occur. I now try to do that with writing so less time is wasted “cleaning up” the mess from the previous day. In both endeavors I spend the last moments awake each night trying to figure out how I will tackle the next steps in the process.

Some woodworking is so complicated that I have to think through processes over and over again; it seems to me writing history is similarly complex, loaded with interdependencies. Mistakes are more obvious in the shop; but if they happen in the shop, they also occur when conducting research, thinking through an argument, developing explanations, and writing. This is a sobering—even fearful—thought. We usually are ignorant of what we do not know or what we missed and how we might have otherwise interpreted the information we have discovered. Did our hypothesis blind us to alternate interpretations or to seemingly irrelevant, but in fact important, evidence? Peer review, good editors, and colleagues who read our work are something of a safeguard, but none are a firewall. Lessons, experience, practice, mistakes, good books, and careful planning and execution make for better woodworking—and better history—but none ensure perfection.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.3 (April, 2008).

Harvey Green, professor of history at Northeastern University and master woodworker, is the author most recently of Wood: Craft, Culture, History (2006). Common-place asked him to reflect on the ways his craft shapes his practice as historian and vice versa.