“Ho for Salt River!”

Politics, loss, and satire

While on a short-term fellowship at the Library Company of Philadelphia beginning my dissertation research, staff in the print department drew my attention to a body of materials labeled “Salt River.” Not entirely knowing what to expect in the folders handed to me, I cautiously rifled through broadsides, invitations, tickets, handbills, and cards of varying color and form ranging in date from the 1840s to the 1870s. As I developed a working knowledge of Salt River and its significance to nineteenth-century readers as a popular symbol for the political defeat of candidates and their respective parties, I became preoccupied not just with the meaning of Salt River but how it was represented in print. Hyperbolic figures, irreverent caricatures, and crude engravings depicting a river voyage juxtaposed with verse, song, and prose paragraphs piqued my curiosity. I could not ignore the richness of a metaphor that represented loss as an experience akin to embarking on a thwarted river journey, the traveler’s equivalent of a slow, gradual death. Similarly, I could not dismiss images that were humorous to nineteenth-century Americans, so accustomed to river travel for leisure, adventure, discovery, or renewal.

Although the precise origin of the phrase “to row up Salt River” in nineteenth-century American vernacular is difficult to verify, folklore suggests some convincing possibilities. The entry in the Dictionary of American History explains that the phrase emerged during the 1832 presidential campaign, which pitted Andrew Jackson against Henry Clay. Clay reportedly hired a boatman to bring him up the Ohio River to Louisville where he was scheduled to deliver a campaign speech. As a supporter of Jackson, however, the boatman, mistakenly or perhaps deliberately, rowed Clay up Salt River, a branch of the Ohio, thus delaying his arrival in Louisville and causing him to miss his speaking appearance. Clay eventually lost the election, but whether or not the boatman’s wrong turn contributed to the loss cannot be proven. According to some scholars, the phrase emerged in an 1839 congressional speech, and by 1840 it had been adopted in campaign songs. Another version of the phrase’s origin story posits that pirates working along the Ohio River diverted vessels up Salt River to loot cargo and rob passengers. In these tales, the boatman and pirates execute their plan heroically or criminally, depending on one’s moral leanings. Whichever of these origin stories one accepts, it seems clear that the cliché “up salt river” originated in real events at a real place. It also seems clear that to Americans accustomed to river travel, the phrase carried a generic and quite humorous message.

But the phrase obviously had meaning for Americans who lived nowhere near the actual Salt River. This may have had to do with its generic content. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), a salt river is a small tidal river located away from a river’s mouth. The lithograph “A Correct Chart of Salt River” (1848) corroborates this definition and reinforces the impression that “up” Salt River implied two unreasonable acts: first, traveling the wrong way up a tributary that by definition flowed down, and second, traveling up an inferior waterway to isolated and irrelevant headwaters (fig. 1). The map projects an imagined path of the river as it branches from the Ohio and weaves around key landmarks before reaching “Lake Oblivion.” The map’s partisan labels reveal allegorical names—such as “Sub Treasury Bluffs,” “Noise and Confusion Shoals,” “Two Face Points,” and “Irish Relief Shoal”—that warn of a difficult, if not a futile journey, while parodying tenets of the Democratic Party’s platform. The OED also suggests a linguistic association of Salt River with a backwoods region inhabited by persons with an “uncultivated manner of speech.” A stock figure in nineteenth-century Kentucky humor was thus the “Salt River Roarer” or a half-horse, half-alligator frontiersman who embodies a masculine, indecorous, and hyperbolic temperament. The character’s boastful and crude humor expresses bravura, defiance, and disrespect, usually unleashed in a stunning verbal rant.

Salt River in Political Caricature

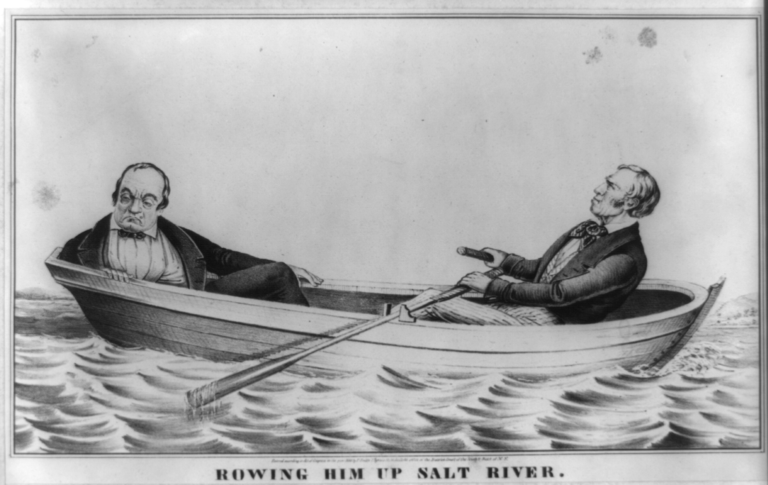

Political cartoonists during the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s employed textual and visual references of Salt River to persuade the public of the strengths and weaknesses of various candidates and to suggest an absence of true political viability. In some lithographs, Salt River holds a prominent presence as the stage upon which debate and confrontation occur. In other representations, political candidates and supporters of one party or another totter precariously above the river’s waters or struggle to stay afloat in its tempestuous swells. Other images suggest a candidate’s likely fate by showing him sitting idly in a decrepit rowboat on Salt River; sometimes a candidate’s fate is implied by a background signpost bearing the ominous words “Salt River.” In the 1840 cartoon “Matty’s Perilous Situation up Salt River” readers witness the slow death of Martin Van Buren, the Democratic candidate for president, who sinks into the water weighed down by the fiscal policies piled haphazardly on his head. Other details in the cartoon reinforce Van Buren’s imminent drowning by depicting the lack of institutional and public support: a hat laden with national newspapers floats away and in the background a building labeled “Humane Society’s Apparatus for the Recovery of Drowned Persons” stands idle. Whig party candidate William Henry Harrison, in contrast, stands confidently on a floating barrel while remarking, “It’s a pity to let the poor fellow drown; I had an idea of making him Inspector of Cabbages of Kinderhook for that’s all he’s good for; but I think he will sink.”

As the phrase “Salt River” percolated through public consciousness, its allusions encompassed more than political defeat. They also suggested the enormous barriers candidates faced. Several cartoons from the presidential campaign of 1848 show Salt River as a foreboding obstacle for all who seek the nation’s highest office. In “Fording Salt River,” the river cuts swiftly through the scene and pushes the White House far into the horizon. We glimpse the Whig candidate Henry Clay submerged head-first underwater with his legs flapping above the surface; Whig candidate Zachary Taylor and Whig supporter Horace Greeley tread neck-deep in the river, while the Democrat Martin Van Buren rides to the water’s edge on the back of his son John. In the same year, “The Modern Colossus. Eighth Wonder of the World” features a more impotent Van Buren, who attempts to straddle Salt River and bridge the two opposite banks, figuratively connecting the platforms of the abolitionist Whigs with that of the proslavery Democratic party. Arms outstretched, he exclaims, “O! I’m gone! I’m gone! I can’t stretch any farther without splitting myself asunder!” These lithographs turn politics into parody by dramatizing the ludicrous futility of establishing any middle ground between the Whig and Democratic platforms. The presence of Salt River minimizes the strength and intellect of the great compromisers; for they will be swept under water or will plunge into the river, unable to plant a foot firmly on either of its banks.

Scholars often draw attention to the abundance of sporting puns and metaphors in nineteenth-century political caricature. Boxing matches, foot races, or bull fights were commonly used to dramatize the competition between candidates and to sensationalize the political contest. Perhaps lithographers chose to filter their political opinions and preferences through such metaphors because they lent themselves to unambiguous interpretation. In sports, unlike politics, there is no moral ambiguity; the best always wins. Salt River brings to mind no such stark contrasts. It signifies a contest that does not depend on strength, bravery, perseverance, and intelligence but rather on sheer fortune. It is the lucky, not the strong or wise, who avoid Salt River. But what of those who find themselves futilely battling the river’s currents? What happens when someone falls into Salt River? If Salt River takes passengers to Lake Oblivion, what does that place look like and what do people do there? These kinds of questions give way to deeper questions: What happens to a party and its candidates after a defeat? What happens to the momentum and emotional investment of the campaign once the disappointing results are known?

Salt River in Ephemera

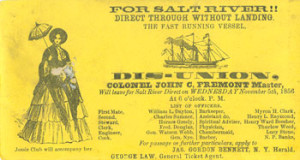

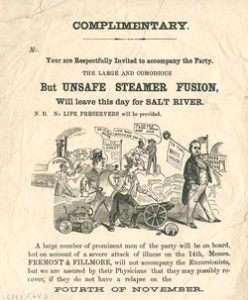

A mock riverboat ticket, for passage on the vessel “Dis-Union,” issued the evening after election day 1856, announces, “For Salt River!! Direct through without Landing” (fig. 2). Another invitation cordially invites you to “accompany the Party. The Large and Comodious But Unsafe Steamer Fusion, Will leave this day for Salt River” (fig. 3). Humor simmers in the irony of a well-equipped but dangerous steamer, which will not stop when it arrives at its destination, and boils to the surface in the elaborate collaboration of graphics and text. The Salt River invitation boldly offers the disclaimer, “N. B. No Life Preservers will be provided,” and Salt River tickets often list the crew who will be on board, casting well-known public figures—presidential and vice-presidential candidates and their advisers and supporters—to serve as captain, pilot, first mate, and steward. Sometimes the puns are not only verbal but visual, as in the example of Mr. Horace Greely and F. Douglass whose last name lends itself to pictures of a donkey (fig. 4). One imagines the tickets, invitations, handbills, and cards tucked into apron or trouser pockets or placed between the leaves of a book by friends and enemies bidding farewell to those about to embark on the campaign trail.

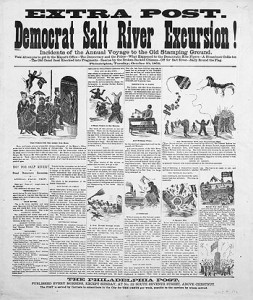

Another common form of Salt River ephemera are broadsides, composed as mock newspaper pages that lay out the narrative of a candidate and his party’s excursion up Salt River. The headline of one of these from the 1871 mayoral campaign in Philadelphia reads at once like a public announcement and a fable of political failure: “Extra Post. Democrat Salt River Excursion! Incidents of the Annual Voyage to the Old Stamping Ground. Vain Attempts to get in the Mayor’s Office—The Democracy and the Politics—What happened to the Democratic Kite Flyers—A Steamboat Collis-ion—The Old Canal Boat Knocked into Fragments—Rescue by the Broken-Backed Citizens—Off for Salt River—Rally Round the Flag” (fig 5). As a variation of the Salt River newspaper broadside, the pamphlet “Salt River Guide for Disappointed Politicians” (New York, 1872), describes the voyage of Horace Greeley and his supporters following the failure of their 1872 bid for the presidency. With Grant reelected president, Greeley, the candidate supported by the Liberal Republicans and Democrats; his running mate, Benjamin Gratz Brown; and a number of their supporters and competitors required rest after the strenuous labors of campaigning. “And what could possibly be so good,” for this purpose, “as the salt breezes of an inland river!” The pamphlet then narrates, in brisk prose and caricature, the canal boat’s voyage to Salt River. Elements of Kentucky humor and the oral tradition of tall tales find a place in the pamphlet’s visual reenactments of the journey and its mishaps. To quell the violent storm that threatens the destruction of crew and boat, Captain Greeley boldly takes command. “Seizing the barometer, he threw it overboard into the angry deep, and the storm at once subsided and they had fair weather in spite of a falling barometer.” The last page presents the reader with the graphic end of a Salt River excursion: “They followed the canal until they reached the historic river where the water is briny and runs up-hill. When once launched on these waters, they turned one against another and became mad—became political cannibals. So the places that knew them once now know them no more, and the crows of fortune pick sadly at their bones, long since washed ashore and innocent of meat.” Not only do Salt River travelers encounter a vicious death, but the river washes them from the public’s memory.

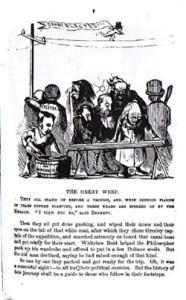

The lasting popularity of the Salt River metaphor invites more than static depictions of failure; it invites an exploration of the idea of failure and the experience of loss. Election issues during these years were contentious and complex, eliciting deep emotional investments by the candidates and their supporters. Policies regarding slavery, suffrage, Reconstruction, secession, and corruption produced impassioned opposition and controversial alternatives. When the stakes were so high and defeat so overwhelming, a difficult question presents itself: how can the excess of disbelief, disappointment, anger, uncertainty, and distrust be adequately and meaningfully contained and represented in print? A scene from the Salt River Guide suggests an answer (fig. 6). Prior to departing, “[the defeated Greeley and his party] gathered together for a last long weep—for a regular drip. Th[e] proprietor of the Herald brought them up before a trough or spout constructed out of planks which composes the Cincinnati platform. They stood up before that spout, at the end of which was a large tub, set by young Bennett to catch the flood of distilled sorrow. And there they opened the flood-gates of their hearts, and a stream of briny water flowed down that spout into the tub.” Here the Salt River image is not a crude jab at the losers but an elegiac meditation on political defeat and the uncertainty of loss in a winner-take-all democracy.

Further Reading:

I examined Salt River ephemera and political cartoons with depictions of Salt River in collections at the Library Company of Philadelphia.

The etymological origins of the phrase “to row [someone] up Salt River” and its variations in select newspapers and literary works are examined thoroughly in Hans Sperber and James N. Tidwell, “Words and Phrases in American Politics: Fact and Fiction About Salt River,” American Speech 26 (1951): 241-47 and more briefly in Lowry Charles Wimberly, “American Political Cant,” American Speech 2:3 (1926): 135-39 and Carl Scherf, “Slang, Slogan and Song in American Politics,” The Social Studies 25:8 (1934): 424-30. These latter two essays are useful for a more comprehensive examination of colloquialisms in nineteenth- and twentieth-century political jargon. An analysis of Salt River in Kentucky humor can be found in Ruel E. Foster, “Kentucky Humor: Salt River Roarer to Ol’ Dog Ring,” Mississippi Quarterly 20:4 (1967): 224-30.

For the history of political cartoons in nineteenth-century America consult Arthur Power Dudden, “The Record of Political Humor,” American Quarterly 37:1 (Spring 1985): 50-70; Stephen Hess and Milton Kaplan, The Ungentlemanly Art: A History of American Political Cartoons, revised ed. (New York, 1975); Allan Nevins and Frank Weitenkampf, A Century of Political Cartoons: Caricature in the United States from 1800 to 1900 (New York, 1944).

For an overview of the material culture of ephemera, see Todd S. Gernes, “Recasting the Culture of Ephemera,” in John Trimbur, ed., Popular Literacy: Studies in Cultural Practices and Poetics (Pittsburgh, Pa., 2001): 107-27.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Liz Hutter, a doctoral candidate in the English department at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, is writing a dissertation on the cultural importance of drowning in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American life.