How Bicycles Liberated Women in Victorian America

On August 30, 1895, May Bragdon and her friends enjoyed “a perfectly delightful day” in and around Rochester, New York. After dinner, the group mounted their bicycles and rode to Ontario Beach Park, arriving just at sunset for a performance of “Pinafore” at the pavilion, where they also relished “the stars & gorgeous moon & colored lights & flowers & sweet air!” Afterward, May and her companions returned home on their “wheels.” “After the first long hill it was simply inexpressibly fine,” May gushed in the pages of her diary that night. “The still, dewy night—the out door odors—the white smooth ro[ad]. The gorgeously bright moon & stars & the sense of freedom & exhilaration of the wheel’s motion!”

Thanks in part to the widespread adoption of the bicycle, the late nineteenth century represented a new era of “freedom & exhilaration” for American women, especially well-to-do white women like May Bragdon and her friends. Although a few intrepid athletes had experimented with the “pennyfarthing” bicycle earlier, in the late 1880s, the introduction of the “safety” bike—featuring pneumatic wheels of the same size—vastly expanded the popularity of “wheeling.” By the mid-1890s, estimates of the number of US bicyclists ranged between 2 and 4 million.

The cycling craze crisscrossed the nation, with cycling clubs and events clustered in western cities such as Denver and Phoenix as well as in eastern cities such as New York and Boston. Enthusiasm for cycling also crossed racial lines—to a point. Although affluent African Americans took up cycling in the 1890s, wheeling remained a racially segregated activity. Even so, Black women eagerly adopted cycling—and excelled at it. Boston native Katherine Towle Knox joined the League of American Wheelmen in 1893, a year before that organization officially excluded African Americans. Knox gained acclaim for her competitive racing, trick riding, and cycling costumes, and she used her unique status to challenge racial segregation. Boston also was home to Irish, Italian, and Chinese cyclists.

Whatever their race or ethnicity, only well-to-do Americans could afford to take up cycling. The high cost of bicycles in the 1890s—between $25 and $50 for a new “wheel,” the equivalent of $800 to $1600 today—was prohibitive for working-class Americans. But above all, cycling was a quintessentially feminine pursuit; indeed, the “safety” bike featured a dropped frame that accommodated women’s long skirts.

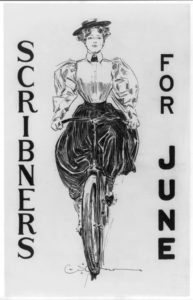

Although members of other groups certainly cycled, the prototypical cyclist in Victorian America was a well-to-do white woman. Public discussions of cycling revolved around the “New Woman,” invariably depicted as young, white, and attractive. Illustrator Charles Dana Gibson popularized the image of the turn-of-the-century’s liberated woman with his drawings of the “Gibson Girl,” who eagerly engaged in sports. Popular publications reinforced the association between women and cycling. “The typical girl of the present period is the bicycle girl,” announced Ladies’ World in 1896. That same year, Bicycling for Ladies offered both practical and fashionable tips for female cyclists.

Victorian social commentators often remarked upon the ways in which bicycles transformed women’s lives. Suffragist Susan B. Anthony proclaimed that the bicycle has “done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.” More cautiously, gynecologist Robert L. Dickinson warned against the sensual possibilities of cycling. While feminists and physicians debated the benefits of the bicycle, the diaries and photographs of one quintessential “New Woman,” May Bragdon, provide greater insight into how this social trend affected daily life.

In the mid-1890s, May and her friends—all middle-class, white, single professionals in their twenties and thirties—went “bicycle-crazy.” They eagerly purchased and compared bicycles, wholeheartedly adopted new fashions adapted to cycling, and enthusiastically supported new spectator sports featuring bicycles, such as races and expositions. But most of all, they thoroughly enjoyed the new freedoms offered by bicycles, which granted them increased mobility, offered new opportunities for outdoor recreation, and led to more spontaneous socializing in both mixed-gender and same-sex groups.

The cycling craze affected both men and women in May’s social circle, which included her brother Claude and his coworker John Constantine “Con” Hillman; her friend Helen Elizabeth “Ned” Dutcher and her fiancé, Will Orchard; sisters Alice, Emma, Mary, and Nellie MacArthur; siblings Charlotte (“Chat”), Frank, Hamilton, Helen, and Katharine (“Kate”) Davis; sisters Agnes, Florence, Mabel, and Mary Rogers; and neighbors Mary “Matie” Hawley, Edith Joiner, and Lura Davis. But it is clear from May’s diary and photographs that cycling most profoundly changed women’s lives, offering them unprecedented opportunities for physical mobility and social freedom.

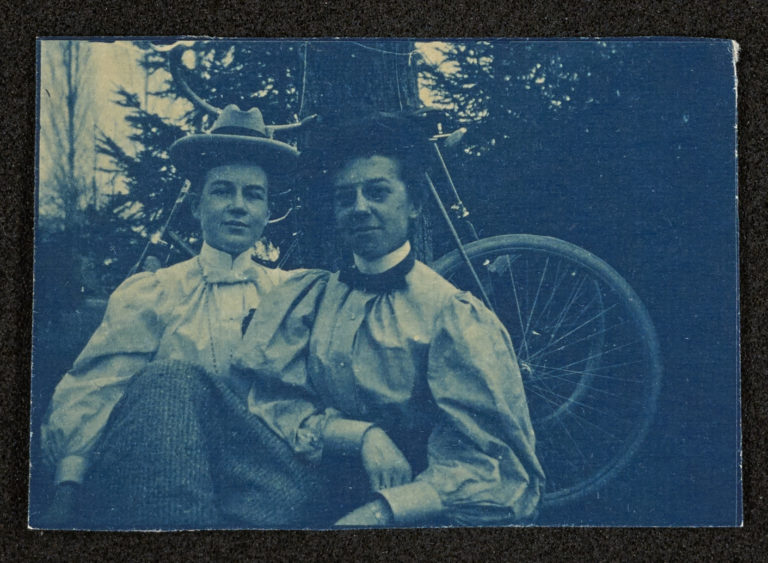

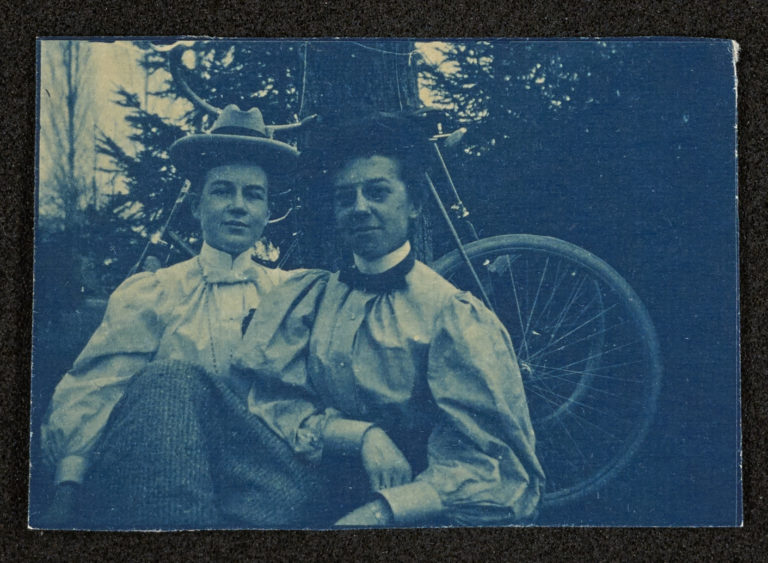

May acquired her first “wheel,” dubbed “Isabella,” in 1893, but while she enjoyed a few “lovely” rides on her own, she confessed that she rode “so seldom” that she “got pretty tired.” This changed in 1895, when her friends began to borrow, rent, and finally purchase bicycles of their own. By that time, May had a new mount, christened “Diana.” She and her friends celebrated their purchases by having May, the group’s unofficial photographer, take Kodaks of them with their steeds.

Although May initially donned “an old shirt waist & skirt” to ride, she and her friends soon saw the benefit of specialized cycling attire: “short skirts” for women and knickers for men. May and her female friends did not go so far as to adopt the loose trousers worn by “bloomer girls,” although May apparently wore bloomers beneath her skirt. Perhaps she adopted this style after a challenging ride she took with Kate Davis, who “had a good deal of trouble with a ‘floppy’ dress—against the wind.”

Instead of donning cumbersome clothing, avid cyclists “dressed for freedom.” While some enterprising young women, like the “Rainy Daisies” of New York City, adopted knee-length skirts, and some dress reformers advocated split skirts or even bloomers, May and her female friends rejected what she deemed the “funny costumes” of the “Bloomer girls.” Instead, they wore modest, but tailored, A-line skirts that stopped a few inches above the ground, just above the tops of their boots. Even so, this style offered women considerably more freedom of movement than skirts that dragged on the ground.

It is likely that May and her friends also dispensed with corsets, rendered unnecessary by the loose-fitting shirtwaist blouses that helped define the “New Woman” in turn-of-the-century America. Certainly May’s photos of herself and her friends sprawled on the ground during breaks from their rides suggest that they were relatively unencumbered by restrictive undergarments.

But for May and her friends, fashion was just as important as freedom of movement. The women each sported a “bicycle hat”—a flat-brimmed straw hat with a ribbon —and May splurged on “a new tailor made bicycle skirt & coat” made from a fine brown wool and a “new silk waist” in a brown-and-cream plaid fabric. Men were not immune to bicycle fashions. One “beautiful warm spring day,” Con Hillman arrived at May’s in “a stunning new bicycle suit—cap to shoes,” which “looked fine.” Con’s ensemble included tall boots, knickers, a turtleneck, a jacket, and a wool cap with a brim.

Fashion was important, at least according to official tastemakers, because cycling was intended as a courting activity. Certainly for some in May’s circle, this was the case. May remarked that during one cycling trip with a mixed-gender group, Helen “Ned” Dutcher and John Stull “‘jollied’ each other, as usual about ‘matrimony’ and we all ‘bon-mot’ed’ for an hour.”

On another occasion, May, Con, Ned, and Will Dutcher, Ned’s fiancé, loaded their wheels onto the train to Niagara Falls, then rode “into town by the loveliest river road,” where “Will pointed out his and Helen’s future home.” They spent the morning at Goat Island, “riding up and down beautiful woody paths and roads,” and then Horseshoe Fall, “where Con & I left Ned & Will at the top & walked down to the brink for half an hour or so of enjoyment of the glories.” In the afternoon, “Mary & Warren appeared,” and the three couples “went across Suspension Bridge & flying up the Canadian shore on a broad—flower-bordered path—Then a duck’ thro the spray—a board-walk & a nice cinder path for a mile or two or more . . . a most thrilling ride on a narrow board ‘Lover’s walk’ that turned at right angles and wound around and about a lovely isle . . . and finally across a funny little Suspension Bridge which ended in a summer house.” After admiring the views, “finally we collected ourselves and rode back again—fast—thro’ the pretty places we had seen, looked at the falls—got drinks of the water & finally reclined on the cool grass in the Park till about train time.” All told, they clocked “about 18 miles wheeling.”

But the day was not over. After arriving at the Rochester train station, the group still had a long and “very beautiful” ride home:

First the beautiful gorge and a glimpse of Lake Ontario shining under the sun and the beautiful Lewiston Valley. Then fair fields & a cool sweet breeze and lovely sunset—a clear pinky sky & few little blue clouds—and soon after a beautiful—almost full—moon which came up and sailed forth to make a night of it—and such a night!

May’s account of this excursion—which began at 7 a.m. and did not conclude until 11 p.m.—showcased beautiful scenery, outdoor exercise, and pleasant company (“We amused ourselves variously—but well,” May remarked). What it did not include was any mention of chaperonage, a staple of nineteenth-century courtship among white, well-to-do Americans. For courting couples, the cycling craze helped to usher in an era of informal socializing, a sort of transition between the restrictive courtship rituals of the Victorian era and the modern practice of dating.

Cycling culture offered individual women, as well as couples, greater freedom in daily life. Although amenable to men’s company, May also thoroughly enjoyed single-sex gatherings. One “fine day” in June 1896, May rode to the Davis house along a new cinder path. “The view is gorgeous all along Highland Ave. and the path runs under the trees very delightfully,” she thrilled. At the Davises’, May dined with Helen, Charlotte, and Frank Davis as well as with their friend Lura Baker. After dinner, Lura went home, Frank went out for the evening, and Helen “Ned” Dutcher joined the group. “Charlotte, Ned & I tried each other’s wheels and saddles &c. &c.” May explained, and the women discussed creating an all-female bicycle club, “The Little Sunbeams,” with Helen as president, Lura as pacemaker, Charlotte as “Lady,” Ned as treasurer, and May as carpenter.

The following day, May recorded another leisurely afternoon that revolved around cycling with other women. “I had a desire to ride today,” she remarked, and so at noon, she took a solo ride through Strathallen Park, then “rode home with Mary [MacArthur].” After dinner, she went back out:

I rode ‘Diana’ to Ned’s & found Edith just arriving . . . We sat around—out doors & in & upstairs & down & talked & finally Ned & I rode & walked down with Edith & I treated them to phosphate on the way. Didn’t get home till considerably after 10—15 miles today.

On yet another occasion, although too much of “a sleepy-head” to accept Mary MacArthur’s invitation to ride in the morning, May found herself unable to resist later that day.

I was just about to settle down to reading when the day was so lovely & Diana so [al]luring that I got on & rode away down to Mary’s, to find her & Alice most willing to come too . . . We rode out to beautiful Genesee Valley Park. We got off on the hill & I took the girls’ pictures under a tree. Then we sat on the grass & listened to the orchestra . . . & then rode out to Sunset seat (thro’ “Lovers’ Lane”) and there I took their pictures again . . . We were going home but I couldn’t bear to leave the beautiful sunset behind, so I suggested we go down Genesee St. . . . Then we rode around those streets & down Chili Avenue into the glorious red West.

The following year, beginning mid-afternoon, May, Helen Davis, Ned Dutcher, and Edith Joiner rode from the Davis home to Sea Breeze Park, 7.5 miles along the Culver Street trail, picking up two other acquaintances, Susan Hoyt and Grace Holmes, along the way. As usual, May enjoyed the ride immensely:

The path is much improved and is beautiful—especially the last three miles or so—one rides under the trees beside the grain fields and with whiffs of pure air from over the bay and fields of wild flowers the other side.

At the turnaround point, the group joined the YWCA’s “Bicycle Tea,” and enjoyed “sherbet and cake &c.” “The grounds overlook Ontario the Beautiful—which was calm & blue,” May described the scene.

The adventure continued:

Helen took us by winding ways thro’ beautiful places & at last emerged on a point overlooking the lake . . . [where] we lay prostrate and watched the lake . . . & told fortunes (a little) and were happy. Then we walked back by the railroad and a pretty bridge and a bit of picturesque road. Then lemonade . . . and started for home about 6:15—and it was a gorgeous ride. The sun was low enough so that the sky & clouds & fields took colors of blues & purples and rose & green—and the air was sweet and it was good to be alive. We rested again near the poplar tree and ate Ned’s sandwiches & Edith’s cookies . . . Helen Davis invited us all home with her to have ‘scrambled eggs &c.’ and Ned, Edith & I accepted . . . We sat about an hour at table (“Chat” with us) recounting our experiences and having a talk. Rode home together about nine o’clock.

In these and other accounts, May highlights the freedom that she and her friends enjoyed. They went out on their own as well as in pairs and groups, with no chaperone and no curfew. They reveled in natural beauty, fresh air, and the feeling of “flying” on their wheels. They set their own schedules, making spur-of-the-moment decisions to meet up with friends, to stop to enjoy refreshments or other entertainments, or to extend their excursion or try a new route.

May Bragdon’s diaries and photographs demonstrate how bicycles liberated well-to-do white women in Victorian America. Suffrage veteran Susan B. Anthony declared that a woman riding a bicycle was the perfect “picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” May expressed the same sentiment more succinctly: “Wheels are fun.”

This piece could not have been written without access to the digitized version of the May Bragdon Diaries, Rare Books, Special Collections & Preservation, University of Rochester River Campus Libraries. Special thanks to Andrea Reithmayr for her assistance with this collection.

For overviews of cycling in the US in the 1890s, see Margaret Guroff, The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016); Heather S. Hatch, “The Bicycle Era in Arizona,” Journal of Arizona History 13, no. 1 (Spring 1972): 33-52; David V. Herlihy, Bicycle: The History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006); Mark E. Pry, “’Everybody Talks Wheels’: The 1890s Bicycle Craze in Phoenix,” Journal of Arizona History 31, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 1-18; Robert A. Smith, A Social History of the Bicycle (New York, NY: American Heritage Press, 1972). For statistics on cycling, see Michael Taylor, “The Bicycle Boom and the Bicycle Bloc: Cycling and Politics in the 1890s,” Indiana Magazine of History 104, no. 3 (September 2008), 215.

On women and cycling, see especially Patricia Marks, Bicycles, Bangs, and Bloomers: The New Woman in the Popular Press (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990); see also Ellen Gruber Garvey, “Reframing the Bicycle: Advertising-Supported Magazines and Scorching Women,” American Quarterly 47, no. 1 (March 1995): 66-69; Sue Macy, “The Devil’s Advance Agent,” American History, October 2011, 42-45; and Lisa S. Strange and Robert S. Brown, “The Bicycle, Women’s Rights, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton,” Women’s Studies 31, no. 5 (2002): 609-626.

On Katherine Knox, see Grace Miller, “Breaking the Cycle: The Kittie Knox Story,” May 26, 2020, Unbound, https://blog.library.si.edu/blog/2020/05/26/breaking-the-cycle-the-kittie-knox-story/#.YfwryvXMIwT. On African Americans and cycling, see Andrew Ritchie, “The League of American Wheelmen, Major Taylor and the ‘Color Question’ in the United States in the 1890s,” Culture, Sport, Society 6, nos. 2-3, (2003): 13-43. For ethnic and racial diversity among cyclists, see Lorenz J. Finison, Boston’s Cycling Craze, 1880-1900: A Story of Race, Sport, and Society (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014).

On cycling and fashion, see Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2021), especially ch. 1. Quotations from Susan B. Anthony and Ladies’ World may be found on pp. 34-35. I am indebted to Dr. Rabinovitch-Fox for corresponding with me about cycling fashions.

On fears that cycling would encourage masturbation, see R. L. Dickinson, “Bicycling for Women from the Standpoint of the Gynecologist,” American Journal of Obstetrics 31, no. 1 (1895): 24-37. Many thanks to Dr. Donna Drucker for sharing her forthcoming essay on Dr. Dickinson with me. Donna J. Drucker, “Shaping the Erotic Body: Technology and Women’s Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century American Medicine,” is forthcoming in Histories of Sexology: Between Science and Politics, ed. Alain Giami and Sharman Levinson (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave, n.d.), 139–52.

On changing courtship practices among middle-class white Americans, see Beth Bailey, From Front Porch to Back Seat: Courtship in Twentieth-Century America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998); Lisa Lindquist Dorr, “Fifty Percent Moonshine and Fifty Percent Moonshine: Social Life and College Youth Culture in Alabama, 1913-1933,” in Manners and Southern History, ed. Ted Ownby (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2007); Heather Ashley Mulliner, “Between the Lines: Friendship, Love, and Marriage in the Progressive-Era Correspondence of Robert and Louise Line” (M.A. thesis, University of Montana, 2012); and Christina Simmons, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

This article originally appeared in April 2022.

Anya Jabour is Regents Professor of History and Director of the Public History Program at the University of Montana. The author, most recently, of Sophonisba Breckinridge: Championing Women’s Activism in Modern America (University of Illinois Press, 2019), she currently is writing a biography of Katharine Bement Davis (1860-1935).