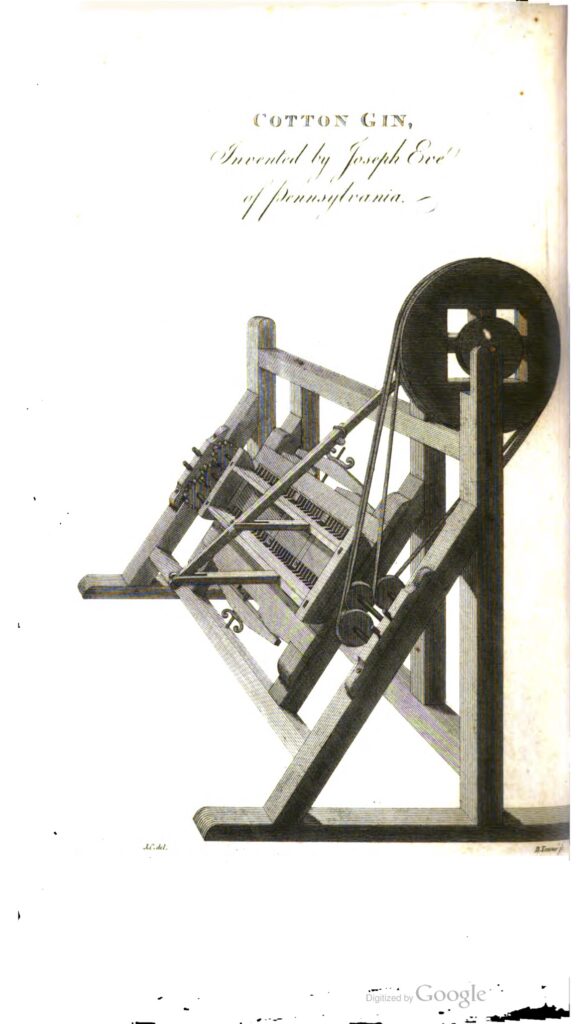

It was in the patent suit that much of the Whitney legend was born. To negate the saw tooth design patent that another gin maker had received, Miller argued that Whitney had already included that idea in his original patent filing. (The inclusion was said to be implicit, because Whitney did not, in fact, mention it at all.) To generate sympathy for Whitney, Miller argued publicly and in court that had it not been for Whitney’s invention, cotton could never have succeeded in much of the South. In other words, Miller presented Whitney as the savior of a declining southern economy, who was pressing his suit only to recover a measure of the recompense he so plainly deserved. The judge largely bought this reasoning and repeated it in his decision. He thereby established the part of the legend by which Whitney’s gin rescued the South from economic stagnation and breathed new life into slavery.

Yet as we have seen, ginning was not a critical barrier to cotton production and improved roller gin designs continued in use for decades after Whitney came along. Moreover, Whitney himself was ultimately only one of many gin makers who improved the gin’s performance. We—meaning people generally in the modern world, but Americans in particular—tend to focus on lone inventor geniuses. But this is rarely how significant innovation actually happens. The case of interchangeable parts shows this even more clearly, so let’s turn our attention to that facet of the Whitney legend.

What Actually Happened, Part 2: Interchangeable Parts

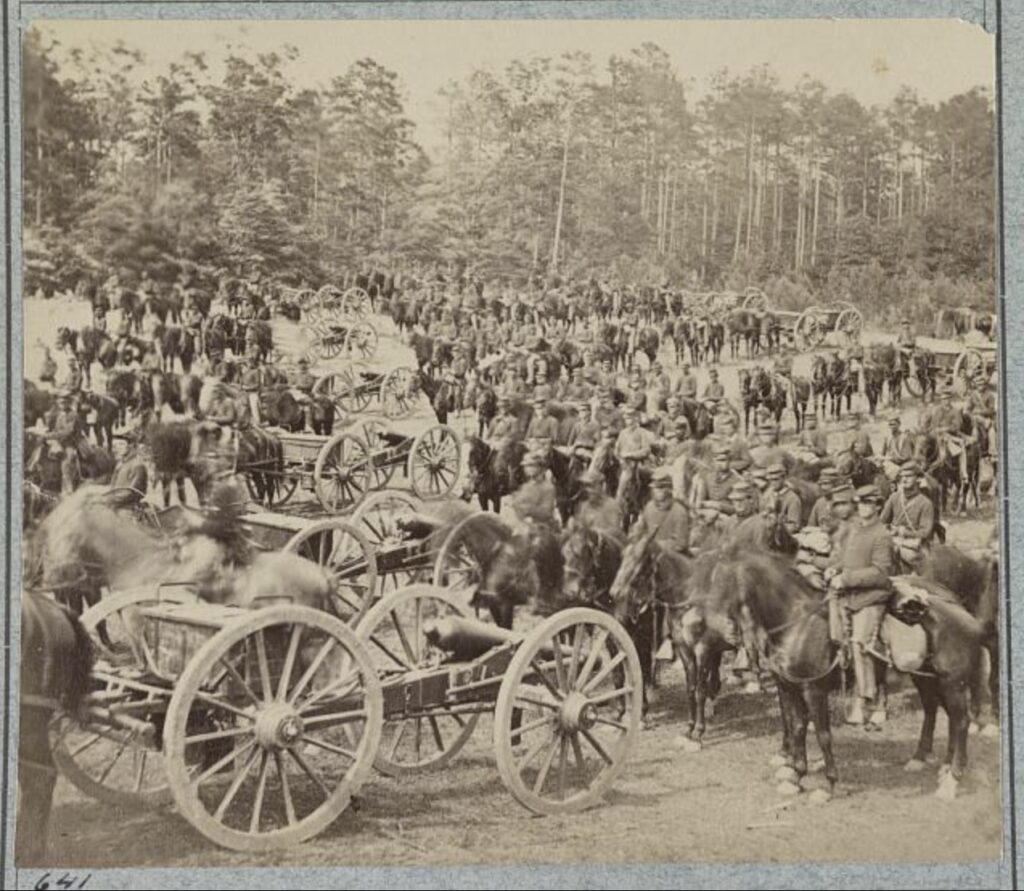

Facing bankruptcy and desperate for credit, Whitney used his elite connections and the fame he had won from his gin design and patent suit, to secure a government contract to manufacture 10,000 muskets in two years. There is no evidence for the story of the reassembled guns that supposedly astonished government officials. Instead, Whitney’s need for money fortuitously coincided with the federal government’s need to appear to be doing something about the possibility of war with France. What better way to seem to be preparing than to make a deal with America’s most famous inventor? The federal government agreed to fund the construction of Whitney’s factory, which was to include advanced machinery that would supersede the need for craft skill.

Whitney ultimately produced the 10,000 guns, but it took him eight years and reams of excuses to do so. He never achieved anything like interchangeability in his lifetime. He did stick with the gun-making business and gradually improved his factory’s performance, which was further improved and modernized by his son in subsequent years. Evidence from Whitney’s factory shows that his gun pieces remained too variable for true interchangeability. Moreover, most of the work was done by hand filing rather than machine milling. During Whitney’s lifetime, the most important approach to machine-based mass production of interchangeable parts was happening in the federal government’s armory at Harper’s Ferry, in what was then still Virginia, under the direction of John Hall.