How to Party Like a President: The Dinners Behind the Dinner Records of Thomas Jefferson

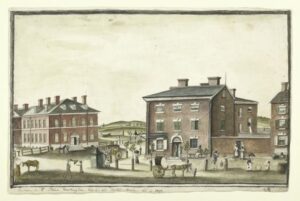

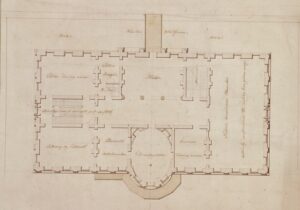

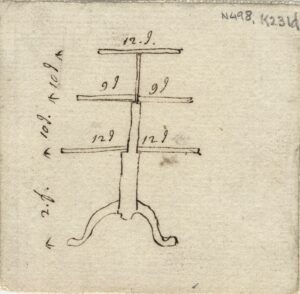

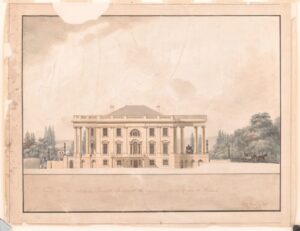

George Washington and John Adams maintained tight social schedules during their presidential administrations: a gentlemen’s levee on Tuesday, a drawing room for mixed company on Friday, and each Thursday a dinner held for deserving members of the political community. The routine gave order to each president’s day, but for members of the developing Republican Party, its forms too closely mimicked those of the British royal court and reeked of monarchism. President Thomas Jefferson immediately eliminated the levees and drawing rooms, but he continued to give dinners—hundreds and hundreds of dinners at tables set for between one and twenty-one guests, and all refashioned to meet Republican sensibilities and his own personal style.

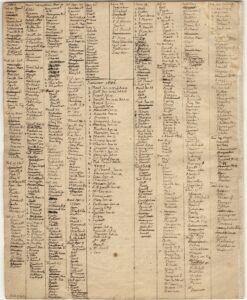

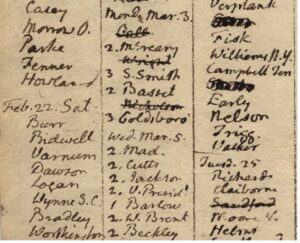

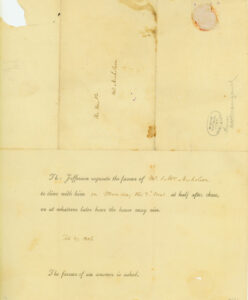

The dinners were not idle entertainment. Jefferson dined members of Congress because it built political camaraderie and helped keep him abreast of political and local affairs. He entertained the established families of Washington City because he appreciated his role in their social season. He entertained the foreign service and special guests to the city because as president of the United States he knew he represented his nation. Because these dinners were business, Jefferson began to keep meticulous records of his guests, beginning on opening day of the second session of the Eighth Congress, Nov. 5, 1804, and ending on Mar. 6, 1809, two days after the inauguration of his successor, James Madison. In all, he recorded almost four hundred dinners in the five-year span, skipping only those periods, twice a year, when he travelled to Monticello.