If the British Won …

Living as I do in Williamsburg, Virginia, I am surrounded by the American Revolution. Here are the buildings where the Revolution was to some considerable extent conceived and here through the programs of Colonial Williamsburg it is reenacted every day. This may explain why I found myself wondering about a world without an American Revolution and why I took it upon myself to read alternate histories (or counterfactuals, as historians tend to call them) in which that was the case.

This was not nearly as formidable as taking on alternate histories in which the South won the Civil War. Those fill many more shelves, and it’s easy to see why. There are still plenty of people who find the Confederacy’s Lost Cause a romantic one and who relish the idea of a triumphant Robert E. Lee. Alternate histories of World War II also abound, presumably not because a Nazi-ruled America is appealing but because it’s irresistibly scary. A British America, in contrast, conjures up little more than a visit from Queen Elizabeth II: a bit of pomp, comfortably familiar and not very exciting.

Historians generally have held this kind of “what-if” history in disdain. In 1961, E. H. Carr called it a “parlor game” and insisted “history is … a record of what people did, not of what they failed to do.” Since then, it’s become a bit more respectable. Historian Gavriel Rosenfeld lists among the reasons the rise of postmodernism in the humanities, with its blurring of the line between fact and fiction; of chaos theory in the sciences, with its emphasis on how small changes can have big results; and of online virtual realities, making historians, like everyone else, more comfortable with the idea of alternate outcomes. And the decline of ideologies such as Marxism, which saw historical trends as predetermined and inevitable, has led to a greater appreciation of how the decisions and actions of individuals, and how sometimes pure chance, can change the course of history.

Still, though historians have played with the genre, alternate history is more often the work of science fiction writers. The genre has also appealed to some mainstream and literary novelists, like Stephen King and Michael Chabon and Philip Roth, and to plenty of readers. The website uchronia.net lists more than 2,000 printed works in the genre. The discussion forum at alternatehistory.comhas more than seven million posts. General anthologies of alternate history, such as Robert Cowley’s What If? series, have been bestsellers.

As for alternate histories of the Revolution, they held enough surprises to keep me reading.

How the British won

Judging from many works in the genre, the easiest way for the British to have won the Revolution would have been never to have fought. A bit more farsightedness on the part of the king’s ministers might have averted the whole nasty business. Roger Thompson’s story, “If I Had Been the Earl of Shelburne,” plays out this scenario. Shelburne’s plan here is simple: take away the colonists’ rallying cry—No taxation without representation—by not taxing them and by giving them seats in Parliament. Among the colonists, too, moderates might have prevailed, as in Edmond Wright’s story, “If I Had Been Benjamin Franklin in the Early 1770s.” Wright’s Franklin mollifies the British by promising Congress will pay for the tea dumped in Boston’s harbor.

Unlike most of the other writers whose work this essay surveys, Thompson and Wright are both historians. This perhaps accounts for their focus on the moments when history might have changed rather than on the long-term results of those changes. Both teach American history in England, which perhaps accounts for their eagerness to see the American “problem” handled, as Wright puts it, “with more delicacy and discretion.”

Once begun, the Revolution’s success was anything but inevitable. Indeed, this is a war that cries out for alternate histories. The actual military history is simply too improbable: an undermanned, underarmed, underfed rabble defeating the world’s most powerful empire. The patriot cause, historian Thomas Fleming wrote, experienced “almost too many moments … on the brink of disaster,” again and again “to be retrieved by the most unlikely accidents or coincidences or choices made by harried men in the heat of conflict.”

Disaster certainly seemed imminent in September 1775. General William Howe’s troops, having defeated Washington’s on Long Island, crossed the East River to Kip’s Bay on Manhattan’s east side, and again routed the Americans. Fortunately for Washington, Howe was satisfied to have secured New York City, and Washington and his army escaped to the north.

In Paul Seabury’s story, “What If George Washington Had Been Captured by General Howe?” Howe gets his man, though he deserves no credit. Seabury presents us with the diary of a Mrs. Murray, who owns an orchard on Murray Hill, not far from Kip’s Bay. Mrs. Murray is mostly worried about the troops ruining her crops. She sees both Washington and Howe on her hill. The latter is more interested in having a drink, but Mrs. Murray takes charge, refusing Howe even a cup of water until he brings back Washington—which, as a result of her prodding, he finally does.

Seabury concludes his story with Howe’s biographer reading the diary, then dismissing Mrs. Murray as a washerwoman and a strumpet and offering to buy the diary, clearly intending to keep its contents secret. This may not qualify Seabury, a political scientist, as a champion of women’s history, and alternate historians of the Revolution have focused on dead white men no less than actual historians—witness the centrality to so many stories of Washington being captured or killed. But Seabury certainly enjoys poking fun at historians who glorify the great men of history, be they Howe or Washington.

Washington is again captured in New York in Gary Blackwood’s novel for teens, Year of the Hangman. The novel’s plot turns on the efforts of its fifteen-year-old hero to save Washington from being hanged. It does not bode well that it is set largely in 1777, a year that began with the hanging of various rebel leaders and in which the three 7s, as Blackwood notes, have shapes distressingly similar to that of gallows.

Washington is also captured in “Washington Shall Hang,” a play that is an alternate history of the Revolution. In Robert Wallace Russell’s story, Washington is put on trial for treason and defended, improbably, by the British colonel, Banastre Tarleton, best known for his bloody cavalry raids and his defeat at the Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina. Here Tarleton redeems himself by outwitting the prosecutors, who have to resort to perjury (from Benedict’s wife, Peggy Arnold) to make sure Washington is found guilty.

Washington’s capture or death is so common in alternate histories of the Revolution that you might wonder why so many writers found it necessary to get rid of Washington in order for the British to prevail. After all, Washington’s successes depended heavily on the flaws of British generals, such as Howe’s hesitation. Washington was no military genius. He was, however, opportunistic, dogged, and inspiring. For a revolution that depended less on defeating the British than on persuading them that America wasn’t worth the trouble of a continuing war, what Washington had to offer was just what was needed. He kept going and he kept his troops going when others would have despaired. He was, as Henry Lee said after Washington’s actual death in 1799, “first in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Had the Revolution been lost, how would the world be different?

For starters, Indians would have been a lot better off. In The Two Georges, a novel by Harry Turtledove and Richard Dreyfuss, the union between Britain and her colonies has lasted into the late twentieth century in which the novel is set, and a few independent Indian nations remain intact in parts of North America.

Native Americans’ fate is more ambiguous in Marc Laidlaw’s short story, “His Powder’d Wig, His Crown of Thornes.” The story appears in an anthology devoted to the question of whether individuals, even “great men,” can truly change the course of history. Here Washington’s death (after being betrayed by Benedict Arnold) leads to the demise of the Revolution, but also to the rise of a secret Indian religion. Grant Innes, a modern-day British trader in Native art, stumbles upon a figure of Washington on the cross. Tracking it through the literally underground world of the American capital (Arnoldsburg, District of Cornwallis), Innes finds a painting much like da Vinci’s Last Supper but with Washington as Christ and his various generals—Knox, Greene, Lee, Lafayette, Rochambeau—as disciples. In the place of Judas is, of course, Arnold.

Innes learns that the Indians blame themselves for Washington’s death and for the world’s subsequent imbalance. As British allies, they scalped his wig and pierced his body with thorns. This, they believe, led to an America that bore factories instead of fruit. “Let no man forget His death,” one of their biblical-sounding books reads. “Forget not his sacrifice, His powder’d wig, His crown of thornes.”

Powerful though the Indians’ faith is in Laidlaw’s story, it seems misplaced. Given the actual history of Native Americans under Washington’s successors, it seems likely that, had the Revolution failed, Indians would generally have been better off.

Blacks, too, would have been better off without the Revolution, at least as portrayed in alternate histories. Turtledove and Dreyfuss assume the abolition of slavery in America would have followed logically from its abolition elsewhere in the British Empire during the 1830s. In the North American Union of The Two Georges, where civil rights were established well before the 1950s and 1960s, the governor general is Sir Martin Luther King.

The fate of blacks is less clear in Charles Coleman Finlay’s story, “We Come Not to Praise Washington.” Finlay’s stories range from alternate history to Arthuriana, sword and sorcery, and horror. Here Washington died in 1793 and the military, led by Alexander Hamilton, has taken over. The cause of freedom for blacks and whites ends up in the hands of an escaped slave named Gabriel, who in actual history organized a failed slave rebellion in 1800.

Overall, alternate historians seem confident the world—and not just Native Americans and African Americans—would have been better off under the British. The combined American and British forces are, for example, unbeatable in “The Charge of Lee’s Brigade,” a story by S. M. Stirling, author of numerous works of alternate history. It’s no coincidence that Stirling’s title conjures up that of Tennyson’s poem, “Charge of the Light Brigade.” In 1854 Brigadier General Lee of the Royal North American Army finds himself fighting for the British in the Crimean War and ordered to lead what seemed likely to be a suicidal charge on the Russian position. Is there a way to seize the Russian guns without condemning half the brigade? If anyone can figure out how to do it, it is Lee, for in a world without a Revolution and thus without a Civil War, this is none other than Robert E. Lee. Students of military history will find this story especially intriguing.

One of the most fully drawn portraits of a modern world in which America is still part of the British Empire is The Two Georges (which must be the only book ever co-authored by a Hugo winner and an Oscar winner). The world Turtledove and Dreyfuss imagine is, however, not fully modern: absent American independence and inventiveness, its steampunk technology is behind ours, with slow-moving though luxurious whale-shaped airships instead of planes and long-distance calls that require operators and patience.

There is much to be said for this world. With the British in control, the world is at peace, despite threats from the Russians and a combined French and Spanish empire. America, too, is a more peaceful place: it’s rare that a member of the Royal American Mounted Police encounters an armed criminal. When a painting is stolen prior to the opening of its tour in Los Angeles—oops, New Liverpool—it is up to Colonel Thomas Bushell of the Mounties to get it back. The painting, which is called “The Two Georges,” portrays George Washington bowing before George III, and it is a symbol of the continuing union between Britain and America. The prime suspects are the Sons of Liberty, extremists who want a free America. These semi-fascist Sons would also like to free the continent of Negroes and Indians.

Dreyfuss and Turtledove draw heavily on and acknowledge the influence of Harry Harrison’s Tunnel Through the Deeps (published in England and in some later American editions as A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!), In Harrison’s novel, the failure of the American Revolution has again resulted in a modern world that’s vaguely Victorian in its technology and manners. This world, too, is somewhat more civilized than our own, a pleasant Tory fantasy of luxury airships and class distinctions. The book will, as the flap copy on the British edition proclaims, “warm the heart of every Englishman … on whom the sun has ever set.”

A few refreshing dystopias

All these worlds where everything works out seem a harsh verdict on a Revolution dedicated to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Granted, the words of the Declaration of Independence obviously did not apply to blacks and Indians—or women, for that matter. Still, would we really want July 4 to be just another day on our British calendars?

For a refreshingly dystopian change, there is S. M. Stirling’s three-volume series, The Domination. In Stirling’s history, Americans win the Revolution but belatedly and with much more bitterness on the part of those loyal to England. Instead of going to Canada, as many loyalists actually did, they settle in South Africa and found the colony of Drakia (named after Francis Drake). Later joined by European aristocrats and Southern Confederates, these losers of our history hold a grudge. They turn Drakia into an empire known as the Domination of the Draka, an empire that fulfilled the dreams of apartheid’s most avid supporters. A common greeting: “Glory to the Race.” The Draka are not only racist but also extraordinarily violent, turning conquered peoples into serfs and soldiers to fuel further conquests.

The first of the trilogy, Marching Through Georgia, is set during World War II, or as it was known in Stirling’s world, the Eurasian War. Having already seized Africa and Asia, the Draka roll over the Nazis and then Western Europe. The second book, Under the Yoke, chronicles the early years of a Cold War between America and the Domination. The third book, The Stone Dogs, carries the Cold War into space, giving the Draka control of earth and exiling the remnants of America to distant corners of the universe.

Stirling provides a great deal of military detail, and the first two parts appeal in particular to fans of military history. By the third book, he has moved into a world that is more fully science fiction, i.e. the focus is on fictionalized science rather than fictionalized history.

Much of the trilogy is written from the perspective of Draka characters, but this in no ways blinds us to the fact that this was a world that would have been better off with our version of the American Revolution. Only a white supremacist would choose the Domination over America. Stirling, however, ought not to be thought of as entirely uncritical of America; after all, the Domination was founded and built by loyalists from the Revolution and Confederates from the Civil War—Americans all. In any case, The Domination is actually less a commentary on the American Revolution than on the Cold War. The question Stirling’s work raises is the one faced by Americans after World War II: How do you fight an empire that is undeniably evil but has weapons that could destroy the world?

For want of a nail

Robert Sobel’s For Want of a Nail … is a comprehensive 450-page history of North America written entirely in the style of an actual history, complete with tables and charts, economic and political analysis, footnotes, bibliography, and acknowledgments. All entirely made up.

Well, not entirely … the opening thirty pages are real history. That takes us to the Battle of Saratoga, often cited as a turning point in the war, since it was this American victory that convinced the French to lend their support. Here the American general Horatio Gates hesitates at a crucial moment, the British general Henry Clinton arrives in time with reinforcements, and the British army of General Johnny Burgoyne deals another blow to the Americans. In the absence of an American victory, the French back away from the Americans, Congress loses faith in Washington and replaces him with a nonentity named Artemas Ward, and moderates led by Pennsylvania’s John Dickinson seize control of Congress from Adams and Jefferson. Franklin opens negotiations with the British, and in 1778 the British agree to generous peace terms. Most rebels are granted amnesty, though a few of the most radical leaders are executed, among them John and Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, and Tom Paine. Washington is sentenced to life in prison.

Next, the British create the Confederation of North America, making the capital Fort Pitt, which in our world became Pittsburgh, and renaming it Burgoyne. Some of the remaining rebels are unwilling to submit to any form of British rule. Led by, among others, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Benedict Arnold, they head west on what comes to be called “the Wilderness Walk.” In Spanish territory, they found the city of Jefferson, which eventually becomes the capital of a new nation, also known as Jefferson.

The nation of Jefferson pushes south and west in its version of manifest destiny (which Jeffersonians call continental destiny). Taking advantage of Spain’s problems in Europe, Andrew Jackson leads a Jefferson army on a conquest of Mexico. Jackson becomes president of what comes to be called the United States of Mexico, which eventually stretches through Arizona and California.

All this is sort of familiar, or at least figures like Jefferson and Jackson act much like themselves, albeit in different circumstances. As Sobel pushes further into the nineteenth century, however, the story focuses on entirely fictional characters. Unlike science fiction writers whose main interest is to portray some alternate world whose history is generally given in flashbacks and often just in passing, Sobel gives us detailed portraits of Jackson’s successors as president of the USM, of the series of wars between the USM and the Confederation, of various depressions and elections, inventions, riots, scandals, genocides, and everything else you’d expect in a history.

Sobel’s adherence to the forms of historical writing extends to including a highly critical review of his work, as might be found in an academic journal. The reviewer—another fictional character—criticizes Sobel’s anti-Mexican bias and suggests as a corrective that the reader refer to various other histories, also fictional. The review makes one wonder whether Sobel’s whole point is to parody the conventions of history writing. For Want of a Nail also reminds us how easy it is for historians to sound authoritative, even if they’re making it all up.

Sobel’s work has inspired a cult following. At the website, “For All Nails,” contributors have submitted hundreds of possible extensions of Sobel’s history up to the present, and some reinterpretations of its past (though the site’s rules prohibit changing any of Sobel’s facts). In its scope, Sobel’s world can legitimately be compared to Tolkien’s or George Lucas’s.

Yet Sobel’s exhaustive approach can also be exhausting. One of the pleasures of great history and great fiction is the originality of the language, and by so fully conforming to the conventions of academic writing, Sobel denies us that. Reading Sobel is like reading a textbook. You can admire it, but you’re not likely to be swept away by it.

In contrast, the best alternate histories make for entertaining reading. You should not expect literary masterpieces, nor should you expect a radically new understanding of the Revolution. You will not learn what the founders really believed about guns or God. But the masters of the genre—and these include Turtledove and Stirling and Harrison—portray vivid and plausible worlds, all emerging from a change of course somewhere in the past.

Like any alternate history, For Want of a Nail demonstrates the power of contingency: a seemingly small tweak, in this case Gates hesitating at Saratoga, changes the course of history. Sobel’s title refers to another such moment: Richard III’s unhorsing at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. This is the moment at which Shakespeare’s Richard offers “my kingdom for a horse.” It is also the moment commemorated in a seventeenth-century poem most often attributed to George Herbert:

For want of a nail the shoe is lost,

For want of a shoe the horse is lost,

For want of a horse the rider is lost,

For want of a rider the message is lost,

For want of a message the battle is lost,

For want of the battle the war is lost,

For want of the war the nation is lost,

All for the want of a horseshoe nail.

Further Reading

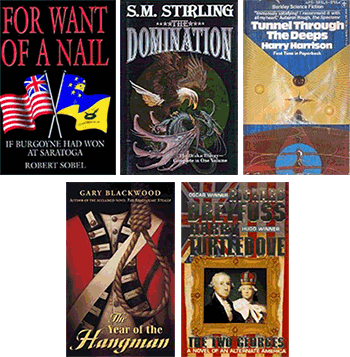

The alternative histories of the Revolution that I have referred to in this essay are the following:

Gary Blackwood, The Year of the Hangman (New York, 2002); Richard Dreyfuss and Harry Turtledove, The Two Georges (New York, 1996); Harry Harrison, Tunnel Through the Deeps (New York, 1972); Charles Coleman Finlay, “We Come Not to Praise Washington,” Wild Things (Burton, Mich., 2005); Marc Laidlaw, “His Powder’d Wig, His Crown of Thornes,” What Might Have Been, Vol. 2, eds. Gregory Benford and Martin H. Greenberg (New York, 1989); Robert Wallace Russell, Washington Shall Hang (New York, 1976); Paul Seabury, “What If George Washington Had Been Captured by General Howe? Mrs. Murray’s War,” What If? Explorations in Social Science Fiction, ed. Nelson W. Polsby (Lexington, Mass., 1982); Robert Sobel, For Want of a Nail: If Burgoyne Had Won at Saratoga (New York, 1973); S. M. Stirling, “The Charge of Lee’s Brigade” Ice, Iron and Gold (San Francisco, 2007); S. M. Stirling, The Domination (Riverdale, N.Y., 1999); Roger Thompson, “If I had been the Earl of Shelburne in 1762-5,” If I Had Been … ed. Daniel Snowman (Totowa, N.J., 1979); Edmond Wright, “If I had been Benjamin Franklin in the Early 1770s,” If I Had Been … ed. Daniel Snowman (Totowa, N.J., 1979).

Portions of this essay first appeared in Colonial Williamsburg: The Journal of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

This article originally appeared in Spring 2014.