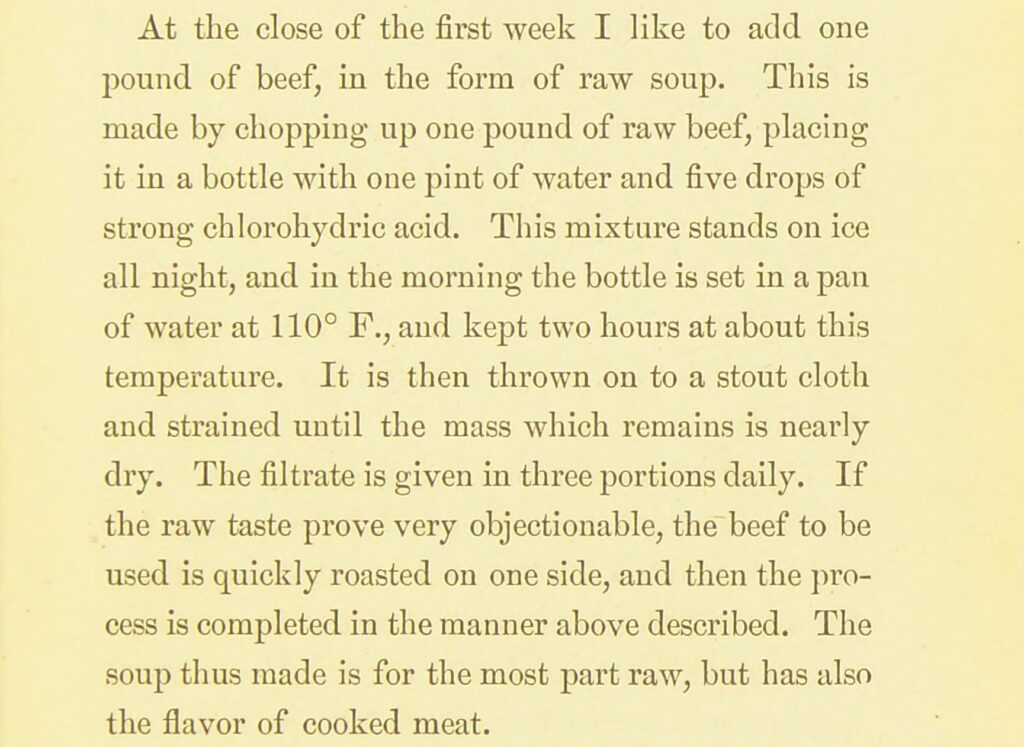

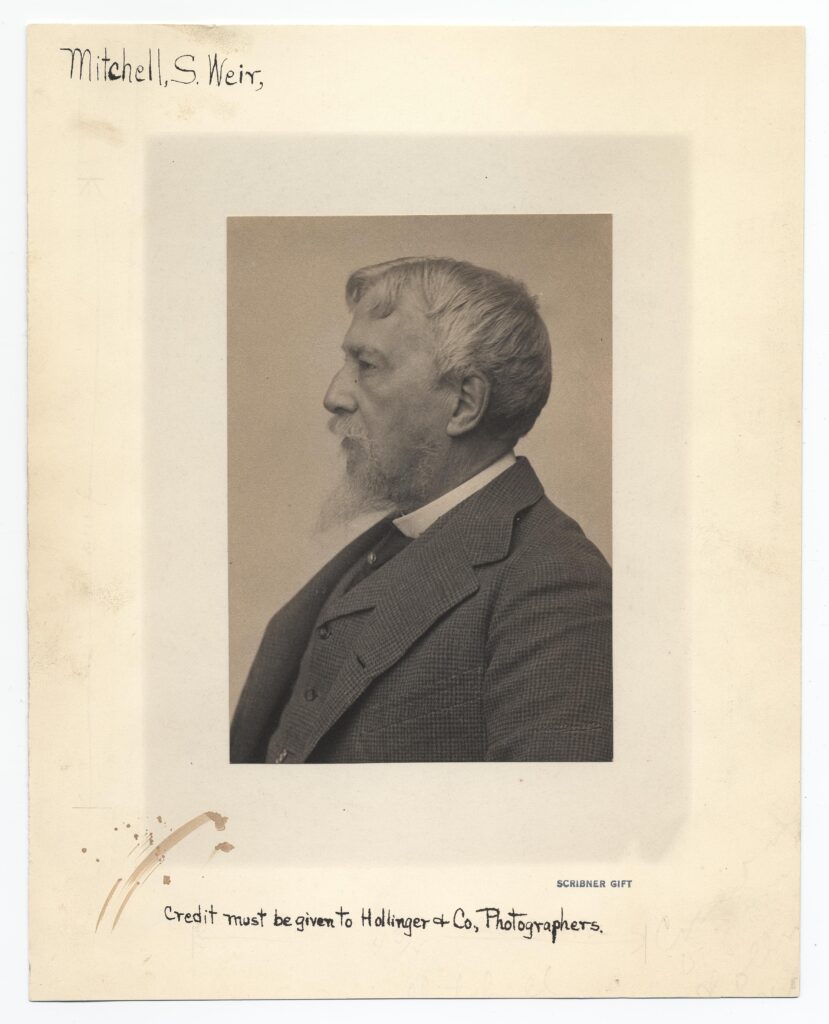

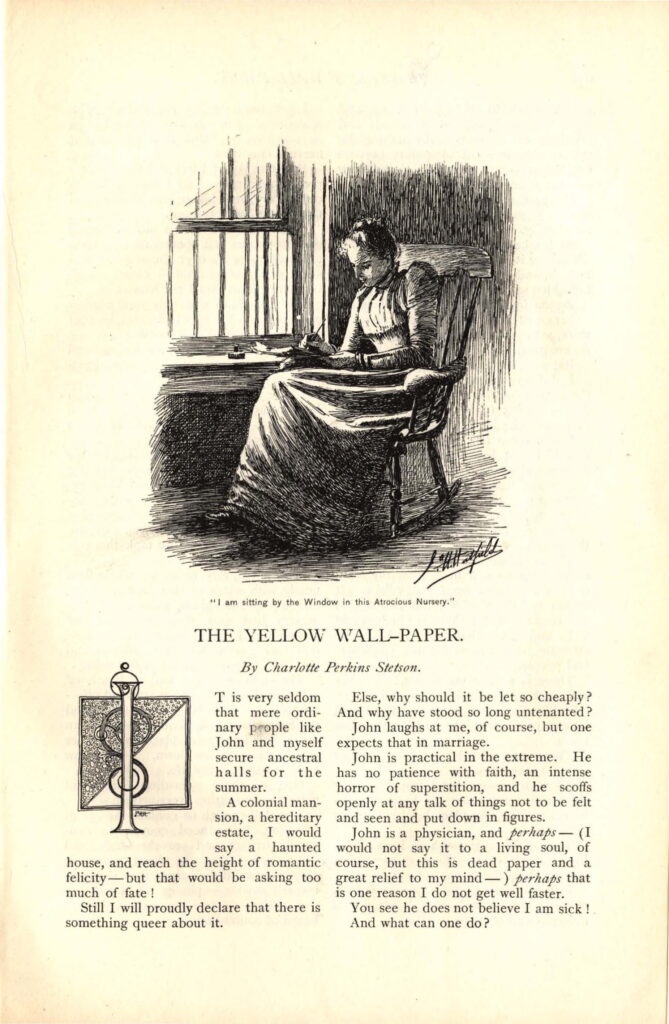

Gilman depicts this uneven power dynamic in the husband/doctor’s insistence that he knows best despite the narrator’s attempt to share her thoughts about her own illness, that she fears she is better in body but not in mind. In response, he insists she really is getting better and pleads, “Can you not trust me as a physician when I tell you so?” (Gilman, 652). I hope readers of my essay recognize by now just how highly ironic this request is, considering deceit and manipulation are baked into the rest cure, as far as Mitchell is concerned. In sum, Mitchell’s rest cure relies on violent governance of bodies. For this reason, the diet component of the rest cure is an integral, if not the primary, method of conquering the patient and as such, diet is a necessary context for future readings of “The Yellow Wall-Paper’s” examination of the patriarchal, exploitative doctor-patient dynamic.

Further Reading:

Page numbers in text refer to Mitchell’s Fat and Blood unless otherwise specified from “The Yellow Wall-Paper.”

Elizabeth Ammons, Conflicting Stories: American Women Writers at the Turn into the Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press, 1991), 35.

Nick Cullather, “The Foreign Policy of the Calorie,” The American Historical Review 112, no. 2, (April, 2007), 337-364.

Cara New Daggett, The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics, and the Politics of Work (Duke University Press, 2019), 4.

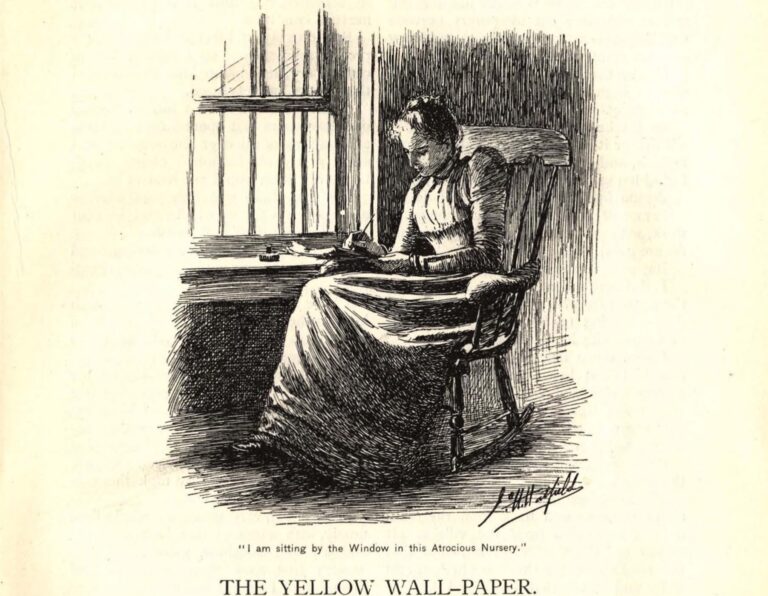

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” New England Magazine 18 (1892), 647-656.

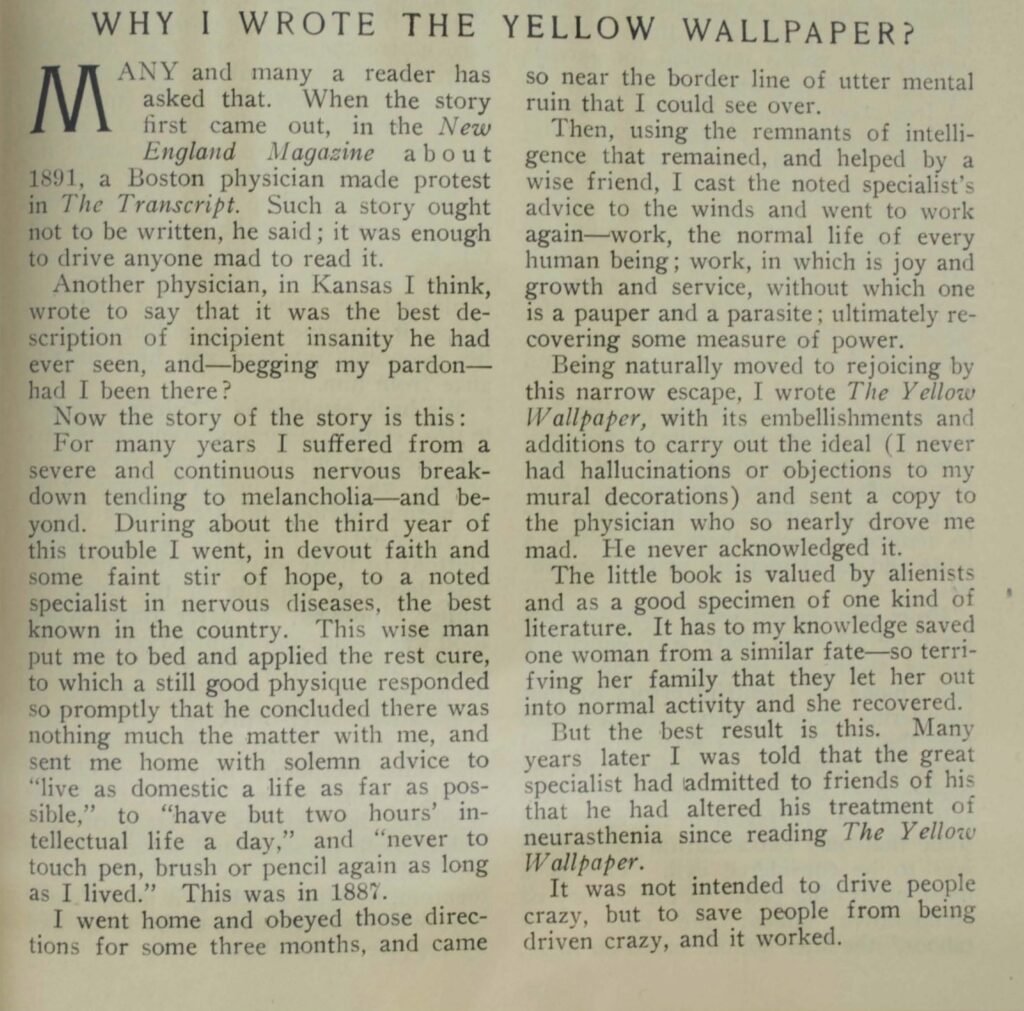

—.“Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper?” The Forerunner 4 (October, 1913), 271.

Edward Harris Goodman, “The Use of the ‘Karell Cure’ in the Treatment of Cardiac, Renal and Hepatic Dropsies,” Archives of Internal Medicine 17, no. 1, (1916), 810.

Philip Karell, “On the Milk Cure,” Edinburgh Medical Journal 12, no. 2, (1866), 97-122. (Quotes from 101 and 102)

Jennifer Lunden, American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman who Brought Me Back to Life (Harper Wave, 2023), 67.

Tom Lutz, American Nervousness, 1903 (Cornell University Press, 1991), 6 and 24.

David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, Narrative Prothesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse (University of Michigan Press, 2000), 205.

Silas Weir Mitchell, Fat and Blood: An Essay on the Treatment of Certain Forms of Neurasthenia and Hysteria 1877, 8th ed. (J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1911).

Fred M. Smith, R. B. Gibson, and Nelda G. Ross, “The Diet in the Treatment of Cardiac Failure” JAMA 88, no. 25, (1927), 1943-1947.

This article originally appeared in February 2025.

Alexis Schmidt is a PhD candidate of English at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She studies work, energy, and exhaustion in turn-of-the-century US literature, primarily written by or about women. Her dissertation is tentatively titled “American Exhaustion: Energy, Bodies, and Literature in the Progressive Era.” Her scholarship has appeared in the Edith Wharton Review and Edge Effects and is also forthcoming in Studies in American Naturalism.