Imitation is the Sincerest Form of Appropriation

Scrapbooks and extra-illustration

As children, my friends and I satirized our teachers and classmates in imitation movie posters and newspapers, devoting at least as much attention to drawing Times Roman type’s thick and thin lines and the serifs on the corners of the letters as we did to our words of mockery. Our teasing seemed to gain power from the familiar, authoritative forms of print, even the ballyhooing cry of the monster-movie poster. (“Thrill to the hunt for x and y! Scream in horror as the amazing Mr. Metzler claims to measure angels!”) We learned to feel we had a stake in these forms of media and turned to them to demonstrate our cultural prowess—if not in math, at least in media.

Making a monster-movie poster or mock newspaper was a way of dressing ourselves in grown-up clothes and taking on the voices that spoke to us with such authority at the movies, in books, and in newspapers. We borrowed that authority to protest the difficulties of our studies and the impositions of our teachers. Our attention to form announced our expertise and gave us a feeling of mastery and control.

Nineteenth-century readers who made scrapbooks also borrowed and imitated the visual and physical trappings of existing, authoritative forms of media to bestow authority on what otherwise might have seemed miscellaneous selections of odds and ends from the newspaper. They turned their ragtag clipping collections into dignified books. While people of all ages, classes, and both genders made scrapbooks, another group, nearly all wealthy men, borrowed and elaborated the form of the book to house collections of prints and to demonstrate their taste and reach as collectors of engravings, etchings, mezzotints, and lithographs. These are the “extra-illustrators” who found in the process of recasting and personalizing books a means to reclaim the luxury and rarity of a printed form that, thanks to mechanized printing, had become commonplace.

Scrapbooks

Americans made scrapbooks to “preserve the good things that fly on the leaves of the winged press,” as one magazine put it. Authors, public speakers, and actors clipped records of their work; suffragists and African Americans documented their collective struggles; women and men of all classes created scrapbooks of poetry, stories, and the miscellaneous-knowledge columns later known as “fun facts.”

Accounts of scrapbook making often feature the family working together to cut apart newspapers and redistribute them into the members’ scrapbooks (fig. 1). In one such account written in 1873, young Hubert “is enamored of voyages and travels, and his big book has become almost a gazetteer. He arranges the articles alphabetically, and we often refer to them for information that we cannot find in books.” The other children in this family have their scrapbooks on housekeeping, cookery, and poetry. There’s Susie’s “Guide to Health” and Charlie’s “Horticultural Guide”; Hartley takes the mechanical and scientific items while “Libbie enjoys the pictures, and the baby glories in the wastepaper.”

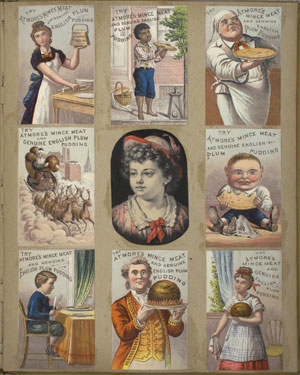

In this account, pictures are decidedly inferior objects—just one step up from wastepaper, entirely for the amusement of the preliterate child. The description accords with the evidence. It was common in the nineteenth century to make cloth scrapbooks—as durable as today’s board books—for young children and to fill them with pictures from seed catalogs, advertising cards, and other sources (fig. 2). Children and young people also made scrapbooks from the colorful and elaborate advertising cards that proliferated in the 1880s (fig. 3). But scrapbooks created to save newspaper and magazine items often used few of the pictures from those publications. Perhaps pictures undercut the seriousness of a homemade object that mimicked the look of a book or newspaper.

The form of the printed magazine or newspaper became more engaging to the nineteenth-century scrapbook makers, who then recirculated the texts among friends or saved them for later enjoyment and reference. Although scrapbook makers had far greater potential freedom in their page composition than magazine and newspaper editors who were bound by the layout restrictions of hot metal type, they rarely used that freedom, instead pasting their collections down in sober parallel columns, imitating the newspapers themselves—no cutting loose in wild diagonals, hardly anything sideways, rarely a heading straddling more than a single column (fig. 4). Indeed, student scrapbooks made in school were sometimes discussed as though they were newspapers.

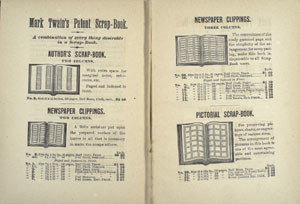

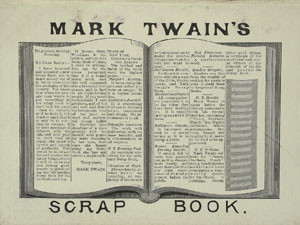

The tendency to imitate the layout of newspapers was encouraged with preformatted scrapbooks such as the one patented by Mark Twain. Twain’s scrapbook was produced in many sizes and advertised with the claim that it would forestall utterances of profanity that resulted from not finding the gluepot (figs. 5 and 6). But not many people used such books.

Densely covering the page had a special appeal for scrapbook makers who pasted their clippings over the pages of printed books, full bookkeeping ledgers, and other discarded records. They preferred to obscure the type, whether it was last year’s Patent Office reports or a book of sermons. The handsome, authoritative bindings of such books seem to have given them special appeal—and certainly such reuse implied a judgment that the original contents were not worth saving.

Margaret Lynn, in a 1914 memoir of her Missouri Valley childhood, recalled that she and her siblings fashioned scrapbooks from agricultural and horticultural reports, a box of which her family received each year. These tedious reports were not blank, but rather were empty of any meaning for Lynn; making them into scrapbooks redeemed them.

From our point of view the books were quite unreadable and almost pitifully useless . . . It didn’t seem possible that so many books should be published with absolutely nothing in them. They were full of pictures, and that was promising, for naturally one expects the presence of pictures to indicate literature of the lighter sort. But such pictures as they were when you came to look at them! Common bugs in all stages of unbeautiful growth; worms only less ugly than in life; hens, mere hens, standing up to have their pictures taken . . . You opened up a nice, shiny, infolded sheet, evidently intended in creation for a beautiful picture, and found it held only drawings of windmills or churns.

Lynn felt a passionate connection to literature, a craving for the company of “folks in books.” But standard literature seemed unconnected to the life around her. The poets she read spoke of flowers she had never seen, and she asked, “Who had ever heard of the Missouri in a novel or a poem?” At least she could collect poetry she admired in the local press and obliterate the hens and worms with it. In other words, in her scrapbook she physically replayed literature’s ability to carry her away from churns.

In one version of this creative act, the essential art lay less in the newly imposed text itself than in the formality with which it was imposed on the scrapbook. Margaret Lynn and her siblings were sometimes particularly attentive in their scrapbook making to “the nice management which brought everything out even at the bottom of the page.” Her brother Henry, who didn’t like poetry, was nonetheless eager to have it for his scrapbook, since it lent itself to book-like blocks of print. “Mary, with her customary readiness of device,” meanwhile, “filled in her inch or half-inch spaces with miscellaneous obituary notices. It didn’t matter if she didn’t know the people, she said; they were dead just the same.” Lynn’s description matches the aesthetic of many book-based scrapbooks. Their makers seem nearly as concerned with obliterating the text beneath as with creating new text.

Extra-Illustration

Commercial publishing changed enormously during the course of the nineteenth century. With the rise of such inventions as the Hoe press, not only did cheap newspapers and magazines proliferate, but so too did affordable books. From a luxury item, available only to well-off Americans, even hard cover books now became affordable and pedestrian consumer goods. To maintain the superior status of their libraries, self-described bibliophiles and “bibliomaniacs” took up book collecting and created categories of rare editions. They also took up “extra-illustrating” or “grangerizing,” turning mass-produced books into forums for displaying their own wealth, taste, and the sheer ability to appropriate the form of the book for their own collecting.

Extra-illustrators took apart existing books, inserting pictures, autographs, and other material with some relationship to the original, often having them expensively rebound. In an extra-illustrated theater history, for example, a reference to the actor “Garrick’s drama of ‘Gulliver in Lilliput'” is followed by three small pictures of Jonathan Swift (each mounted on a full page), playbills, a two-page print depicting Gulliver at Brobdingnag and a series of other tangentially related illustrations. When an extra-illustrator was done with it, a 250-page book might have been enlarged to ten volumes. Extra-illustration transformed ordinary books into a frame or armature for the compiler’s collection of visual images; sometimes the leaves of the original text are hard to find between the pages of prints.

The extra-illustration fad started in eighteenth-century England as a way for gentlemen to demonstrate their wealth and taste by essentially recreating a book with costly prints. For these extra-illustrators, there was nothing sacrosanct about either the form or market value of a book. It was, like the homes they improved, another arena in which to demonstrate ownership and taste.

In 1769, James Granger, who gave his name to the extra-illustration fad, published a two-volume Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution with the express purpose of serving extra-illustrators. As the book’s full title noted, it was adapted to a methodical catalogue of engraved British heads . . . with a preface showing the utility of a collection of engraved portraits. Print sellers eventually saw in the grangerizers an opportunity for sales. In the late 1700s they began commissioning specific sets of prints to be sold along with books that were particularly popular with extra-illustrators. Sets of illustrations for these works were sometimes keyed to the correct page number.

To ensure that the extra-illustrated book would not be mistaken for a scrapbook, one authority explained that grangerizers should add magazine and newspaper articles only if they had the paper split (literally separating its front and back faces), so that type appeared only on one side—something the average scrapbook-maker could not afford. Such an article would evidently be valued for its now specialized visual qualities and the expense of preparing it for extra-illustration, not just for its particular content.

Much like their British counterparts, American grangerizers often embellished works of historical importance. Curtis Guild (1827-1911), founder and editor of the Boston newspaper the Commercial Bulletin, included in his oeuvre an elaborately extra-illustrated life of George Washington as well as one of Ben Franklin. He defended his work against bibliophiles who condemned grangerizers for destroying valuable books by asserting that picture dealers who served grangerizers purchase “old or damaged books, odd volumes, magazines, and pamphlets containing portraits, which they carefully extract, cleanse, and prepare for sale.” Though they break up books, the extracted pictures sell for much more in the aggregate than “the stupid old volume, and the plates distributed do better service and contribute to further enrich an already interesting and valuable volume by being inserted therein.”

Guild hailed the extra-illustrator as a public servant. In illustrating Washington Irving’s Life of Washington, for example, he had gathered “autographic letters, choice old prints, plans, proclamations . . . and curious Revolutionary documents,” which by the end of the nineteenth century had become too scarce, because they had been “taken by collectors or museums, or have become lost or scattered.” Binding them into a book “in sumptuous dress” for his own private library seemed to a collector like Guild essential to “preserving” an orderly record of America’s past, even as it removed them from the public domain.

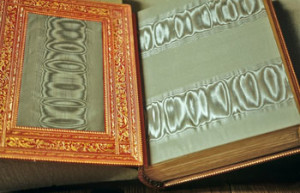

Guild’s method is perhaps best illustrated by the title of his Franklin book. The original was simply Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin,written by James Parton and published in New York in 1864. In a special title page Guild had printed for his version of the work he appended the following to the original title: Extended and Illustrated by the insertion of Portraits, Views, Engravings, Manuscripts, Curious Printed Documents, Original Autographic Letters, etc. collected from various sources in Europe and America by Curtis Guild, Boston, 1881 (figs. 7 and 8).

Among the eclectic items encompassed by this description was a page from Parton’s manuscript (actually copied by Parton from the printed version since, by the time Guild asked for the item, Parton no longer had the original) and illustrations having only the most tangential connection to the text. So, for example, where Parton notes that the word “Franklin” appears in Chaucer, Guild adds an engraving of Chaucer.

The willfully tangential quality of the illustrations, illustrating terms that even an indexer would skip, suggests that Guild was not seeking to make his copy of the text more useful, but rather was playing with the skeleton of the book, improvising far away from the melody. He thus showed his virtuoso ability to reach into odd corners of visual culture and supply references to nearly anything. And of course he demonstrated the reach of his purse. Fortunately, he underlined in pencil the word or line in the text to which the added illustrations referred. Otherwise, it would sometimes be impossible to determine the logic behind his extra-illustrating. Reading an extra-illustrated book is like going on a treasure hunt, searching for the connections the maker might have had in mind and thereby putting the work of that bibliophile, rather than the author, front and center.

In addition to books about the founders, books about famous American authors were common subjects for American grangerizers. Several extra-illustrators, for example, produced grangerized copies of prominent Boston publisher James T. Fields’s Yesterdays with Authors (1872). The book’s purpose had been to celebrate American authors by putting them on the same footing with British authors. It therefore included anecdotes about visits with Dickens side by side with vignettes celebrating the genius of Hawthorne. The book drew heavily on Fields’s correspondence, and later editions came ready-illustrated with engravings of authors and facsimile autographs. Extra-illustrators jumped in as fans, demonstrating their connections with the authors, their power to procure autographed correspondence written by them, as well as actual letters by Fields. The grangerizer, too, as any reader would see, could navigate the waters of literary celebrity.

Curtis Guild transformed his 1887 edition of Yesterdays with Authors by adding 250 portraits and views and 105 original autographs and manuscripts, so that it took up four volumes. Not content with adding visual marginalia to Fields’s book, Guild took another step and wrote a book, elaborating his work on Fields’s book. Guild’s A Chat about Celebrities, published in 1897 by Boston publishers Lee and Shepard, presents his own anecdotes about celebrities and connects them to the pictures and autographs he used to illustrate Fields’s book. It was essentially a set of verbal glosses on his visual glosses on Fields’s book, now far removed from Fields.

Friendly reviewers praised Guild for the intimacy the book offered. “Although there is not much method in such a book of chatty reminiscences,” still, they are entertainingly given. The book starts the reader with Fields’s coterie at the Old Corner Bookstore in Boston, from which “he is conducted to England’s memorial spots, and . . . shakes hands with Thackeray and Wilkie Collins,” California’s Overland Monthly noted. The origin of this admiring review hints at the attraction Guild’s book might have had for readers far from the centers of the literary universe. With such a text, the reader in distant California gains an intimate glimpse of the literary world into which this industrious grangerizer had inserted himself.

The self-consciously iconoclastic little magazine the Chap-Book, on the other hand, went straight for the economics of extra-illustration that underlay A Chat about Celebrities: “The startling fact that he owns a book on which he has spent Four Hundred Dollars constitutes the chief interest of Mr. Guild’s latest publication . . . when he is not speaking of himself or of the Three Hundred and Sixty-Four Things he bought with his Four Hundred Dollars, he is seldom at his best.” The Chap-Book understood that the extra-illustrated book is really a book about its maker and his spending power.

Prominent grangerizers like Guild and Robert Hoe, who extra-illustrated thirty different copies of the same edition of Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler, among other works, were intimately involved in the mass production of print—Guild as a newspaper publisher, Hoe as a member of the family firm responsible for the rotary presses that helped make print cheap enough for scrapbook makers to clip with abandon. They hardly needed to borrow the form of the newspaper to endow their works with grandeur, as scrapbook makers did. But their involvement in extra-illustration and in collecting rare books set them apart from scrapbook makers who used Hoe and Guild’s products.

Grangerizers were sometimes explicit about their desire to distinguish themselves from scrapbook makers. “I do not approve of haphazard commercial products made up of half-tones from magazines and fragments of documents and signatures inserted,” one collector (and autograph dealer) wrote. An extra-illustrated book, in contrast, should collect “fine impressions of scarce engravings and interesting autograph letters.” The result should exhibit the grangerizer’s “cultivated and disciplined mind.” Discipline in choosing would ensure that the extra-illustrator would not “make a picture scrap-book of [his] volumes.”

As technological change made magazine and book illustrations cheaper and more common, grangerizing fell out of fashion. What was the thrill of showing off a handsomely bound book full of pictures, when a door-to-door salesman of subscription books had a suitcase full of them? There was little point in demonstrating one’s power to lavishly illustrate if nearly everyone could not only afford richly illustrated texts but could easily obtain images from a rapidly proliferating universe of cheaply reproduced photographic images.

While extra-illustrators prized their works according to the rarity of the materials they obtained for them, scrapbook makers took the mass-produced press and created unique objects from it by selecting and organizing its contents according to their own tastes and interests. The scrapbooks they left behind offer insights into their reading and participation in the press as readers, clippers, and imitators.

Further Reading:

The 1873 visitor to a scrapbook-making family was Julia Colman, in her “Among the Scrap-books,” The Ladies’ Repository, August 1873. Margaret Lynn’s reminiscences can be found in her A Stepdaughter of the Prairie (New York, 1914) and of clipping scrapbooks in my “Scissorizing and Scrapbooks: Nineteenth Century Reading, Remaking, and Recirculating,” in Lisa Gitelman and Geoff Pingree, eds., New Media: 1740-1915 (Cambridge, Mass., 2003). A longer consideration of children’s advertising scrapbooks is in my The Adman in the Parlor: Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture, 1880s-1910s (New York, 1996). For more on other types of scrapbooks see Susan Tucker et al., eds, The Scrapbook in American Life (Philadelphia, 2006).

Curtis Guild’s comments on his grangerizing work are in A Chat About Celebrities, or The Story of a Book (Boston, 1897); the unfriendly unsigned review is in the Chap-Book (July 1, 1897); the autograph dealer Thomas Madigan made his comments in his Word Shadows of the Great: The Lure of Autograph Collecting (New York, 1930); remarks contrasting the grangerized book with the scrapbook are in Daniel Tredwell, A Monograph on Privately Illustrated Books: A Plea for Bibliomania (Long Island, N.Y., 1892). For more on the history and uses of extra-illustrated books in England, important sources include articles by Lucy Peltz, “The Pleasure of the Book: Extra-Illustration, an 18th-Century Fashion,” things 8 (Summer 1998) and “The Extra-Illustration of London: The Gendered Spaces and Practices of Antiquarianism in the Late Eighteenth Century,” in Martin Myrone and Lucy Peltz, eds., Producing the Past: Aspects of Antiquarian Culture and Practice 1700-1850 (Aldershot, Hampshire, 1999); the chapter “Illustrious Heads” in Marcia Pointon’s Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven, 1993); and Robert A. Shaddy’s “Grangerizing: One of the Unfortunate Stages of Bibliomania,” The Book Collector (Winter 2000).

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Ellen Gruber Garvey is the author of The Adman in the Parlor: Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture and is writing a book on nineteenth-century readers’ interactions with the press, Book, Paper, Scissors: Scrapbooks Remake Nineteenth Century Print Culture. She is an associate professor of English at New Jersey City University.