Impressions of Tar and Feathers: The “New American Suit” in Mezzotint, 1774-84

On a frigid Boston night in January 1774, a crowd of American colonials tarred and feathered a hated customs official. Nine months later, after this news had crossed the Atlantic Ocean, London publishers Robert Sayer (1725-1794) and John Bennett (c. 1745-1787) issued an imagined depiction of the event (fig. 1). The scene takes place beneath the broad branches of the Liberty Tree, onto which a copy of the 1765 Stamp Act has been tacked, upside down, as a reminder of the Americans’ triumph in their most recent conflict with Parliament. A tar brush and bucket sit in the foreground, while a noose hangs menacingly from a branch overhead. Five Bostonians pour tea into the mouth of the tarred-and-feathered figure, who appears to be more bird than man, an almost bestial creature with horns led by a rope around his neck. In the background, five men empty chests of tea from the deck of a ship into the water below in one of the earliest depictions of the so-called Boston Tea Party.

This print has become one of the most widely reproduced emblems of the American Revolution.

Titled Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man, or Tarring & Feathering, this print has become one of the most widely reproduced emblems of the American Revolution. In the centuries following its initial appearance, the design was repeatedly remade and reinterpreted, as it was drawn onto lithographic stones, engraved into blocks of wood, encased in shellwork frames to decorate domestic interiors, and included in numerous American history textbooks. Through a study of the print’s publication, Sayer & Bennett’s mezzotint emerges as both a fascinating historical document and as a material thing that is intimately and inseparably connected to the hands that engraved, inked, pulled, stacked, shipped, and framed it. As we track Tarring & Feathering through its earliest years, the print materially registers the tensions inherent in portraying American unification and imperial fragmentation through English eyes.

The Man in the Suit

Six weeks after chests of tea were emptied into the Boston Harbor, the customs agent John Malcom (1723-1788) struck shoemaker George Robert Twelves Hewes with his metal-tipped cane on a Boston street. In response, a crowd of Bostonians tarred and feathered Malcom, a zealous supporter of royal authority. In March 1774, the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser (London) detailed the narrative sequence of the evening’s events:

“ . . . they tore his cloaths off, and tarr’d his head and body, and feathered him, then set him in a chair in the cart, and carried him . . . into King Street, from whence they proceeded to the Liberty Tree . . . then as far as the Gallows, where they . . . threatened to hang him . . . . It is said he was near four hours in the[se] conditions, and that he was so benumbed by the coldness of the weather, and his nakedness, and bruised in such a manner that his life is despaired of.”

Contrary to this dire prediction, Malcom survived his ordeal and sailed to London three months later to petition the king for compensation for his suffering. While awaiting a reply to his request to be made a “Knight of the Tar” (or, at the very least, to be appointed to a more lucrative post within the American customs service), Malcom undertook a second campaign: he stood for election to the House of Commons, audaciously running against the controversial politician John Wilkes. As an alderman for the City of London and wildly popular “friend of freedom,” Wilkes’s agitations within the British government during the 1760s and 1770s catalyzed constitutional reform by raising questions about the rights and autonomy of the British electorate and the relationship of the legislature to the Crown.

On October 12, 1774, roughly a week before the election was to take place, designer and engraver Francis Edward Adams (1745-1777) published the first print representing Malcom’s ordeal, titled A New Method of Macarony Making, as practised at Boston (fig. 2). Might Malcom have collaborated with Adams to produce this print in conjunction with the upcoming election? If he had consciously sought out an engraver who shared his feelings about Wilkes, Adams was the right man for the job. In another print that the engraver published the same month, Polling for Members, or a Lesson for a New Parliament (fig. 3), “Lord Patriot” (that is, a supporter of Wilkes) is shown losing the election by a landslide.

Accordingly, A New Method of Macarony Making presents its subject as a sympathetic martyr. The four lines of verse beneath the print encourage its readers not only to connect the Boston Tea Party and Malcom’s treatment but to believe that one caused the other: “For the Custom House Officers landing the Tea / They Tarr’d him, and Feather’d him, just as you see.” In other words, Malcom’s treatment was caused not by his own aggressive actions in assaulting a tradesman with his cane, but because, as a loyal customs officer, he had participated in allowing the ships bearing the tea belonging to the East India Company to dock in the Boston harbor. While the atmosphere in Boston certainly crackled with tension in January 1774, as the city waited to hear how the British government would respond to their destruction of the tea, the print’s verses bear little relationship to the truth. Instead, this highly convenient spin paints Malcom in the most flattering light. Malcom’s depiction also contributes to this impression. He appears as an abject sufferer, piously clasping his hands in prayer, unquestionably worthy of sympathy. His tormentors blatantly parade their allegiance to John Wilkes through the adornments on their hats: one wears a cockade, while the double inscription of “45” references the issue of Wilkes’s periodical The North Briton that led to his arrest on charges of seditious libel for criticizing the king. As this print sought to appeal to those with loyalties to the Crown and its ministers, the Americans’ support of Wilkes is held up for ridicule, echoing Malcom’s own appeal to voters in which he characterized Wilkes as a “mock patriot” and a “hypocritical hireling.”

Despite Malcom’s strong words and active campaigning through text and images, neither he nor any other candidates appeared at the poll on voting day to challenge Wilkes, who won the election by default. But on October 31, soon after the final poll was returned from the Parliamentary election, Tarring & Feathering appeared in Sayer & Bennett’s print shop window. Located at No. 53 Fleet Street, on the major commercial byway between the City of London and the Houses of Parliament, Sayer & Bennett’s 25-year-old firm was one of the largest publishing houses in the competitive London print industry, with a robust wholesale business that sold prints, maps, and books to retailers in English and American provincial towns. Generally speaking, they took few risks in what they published and tended to purchase or commission prints after their popularity with buyers had been previously established. In this instance, Adams’s print—A New Method of Macarony Making—acted as the bellwether for the subject’s appeal on the market, where it clearly had found traction.

But Tarring & Feathering is far more than a simple recapitulation of A New Method of Macarony Making. Placed alongside one another, Adams’s print appears supportive of the British government, while Sayer’s seems to align with the opposition party—not wishing for, or even considering, a civil war that will lead to American independence, but championing a group taking a principled stand against oppressive laws. On one hand, this polarized description aligns well with what we know about Sayer’s politics. Put bluntly, Malcom’s denouncements of John Wilkes would have sounded like fighting words to the publisher, who had voted for the opposition politician in 1768 and published multiple prints in support of Wilkes shortly thereafter. As much as one can understand a person’s politics through the objects he published, Sayer seems not to have been particularly radical in either his beliefs or his publications. But London electoral records from 1768 to 1784 show that he repeatedly voted for opposition candidates who were critical of the king’s administrations.

However, let me register a cautionary note: it paints far too neat a picture to portray British opinions about Americans as polarized or cleanly divided in 1774. For example, few British politicians or members of the broader public felt positively about the Boston Tea Party, due to its destruction of property and threat to imperial accord. Even those such as Edmund Burke who would later raise their voices in Parliament to protest punitive legislation in response to the Boston Tea Party wanted not to redefine the relationship between the mother country and her colonies, but simply to attempt a conciliatory approach before turning to a military solution. Accordingly, to interpret Tarring & Feathering as portraying either an entirely supportive or an entirely critical viewpoint toward the Americans’ rebellious actions would oversimplify the many contradictions that faced the British population as they argued over how to define their empire.

Interpreting Tar and Feathers

What, then, are the fine-grained differences between these two prints of the “new American suit”? Sayer & Bennett’s mezzotint also persuaded its viewers to connect recent events in Boston, but in the service of a different message. Tarring & Feathering’s designer incorporated a second newspaper article, published in the St. James’s Chronicle three months after the first (quoted above), which made one specific moment during that January evening stand for the whole. The report described that, during a pause on Malcom’s journey through Boston, someone in the crowd handed him a “large bowl of strong tea” and told him to drink multiple toasts to the king and his family. As “the drenching Horn was put to his Mouth” for Malcom’s final toast,

“. . . he turned pale, shook his Head, and instantly filled the Bowl which he had just emptied. What, says the loyal American, are you sick of the Royal Family? No, replies Malcolmb [sic], my Stomach nauseates the Tea, it rises at it like Poison. And yet, you Rascal, returns the American, your whole Fraternity of the Custom House would drench us with this Poison, and we are to have our Throats cut if it won’t stay upon our Stomachs.”

As the satirical article implied, the Americans’ dealings with Malcom, and their particularly apt form of torture, were intended to shed light on Britain’s policies of taxation and subsequent punishment of the American colonies. This equivalence is echoed by the formal similarity between the streams of tea pouring out of their crates and the streams of liquid expelled by Malcom. In turn, the print crafts a narrative connecting the colonials’ acts of rebellion, building from the Stamp Act crisis of 1765, to the Boston Tea Party, to the increasing occurrences of tar and feathers in the 1770s.

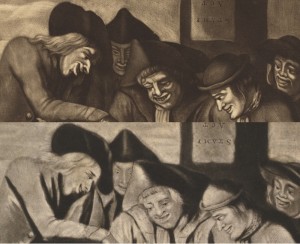

Londoners were simultaneously horrified and intrigued by tarring and feathering. A form of crowd violence adopted from medieval folk culture, the practice had become a popular and effective means of intimidation, coercion, and protest in British North America, beginning with the Stamp Act protests in the mid-1760s. The expressions on the men’s faces in both prints would have confirmed many stereotypes of Americans’ lack of civility. But the smiles worn by the Bostonians in A New Method of Macarony Making seem more mirthful than vengeful. With their showy suits of striped breeches and patterned waistcoats, the affect of these two figures decreases the legitimacy of their threat. In contrast, the Americans in Sayer & Bennett’s mezzotint appear fully capable of enacting the bodily harm they are inflicting upon their victim. Their grotesque expressions contribute to this communication of their power. Close examination of the cackles of glee contorting their faces reveals hints that the five aggressors wear masks (fig. 4). The faces of the two figures in the background appear flattened and simplified, with abstracted forms shaping their eyes, noses, and mouths. And on each of the other three figures, a line appears along their jawlines, suggesting a whitened mask resting on top of the skin beneath.

These masks help situate this scene of tarring and feathering within a long tradition of rites of reversal. Events such as the carnival, or the “world turned upside down,” had long been sanctioned as a means of limiting unrest by permitting a temporary inversion of the social order. Sayer & Bennett’s mezzotint reverberates with class as well as political differences. During the altercation that led to his tarring and feathering, Malcom reprimanded Hewes that a shoemaker “should not speak to a gentleman [that is, Malcom] in the street.” As a naval officer, Malcom saw himself as belonging to a different social group than the men of the middling and laboring classes who populate the mezzotint. At the right, a sailor is identifiable by his “slops” and spotted neckerchief, while the man at the center wears a greatcoat over what appears to be a leather apron, a common garment of artisans such as blacksmiths, carpenters, and printers. And while the man at the left wears a suit, his elbow protrudes through a tear in the sleeve.

In practice, gentlemen were nearly as apt to tar-and-feather (or at least support or condone the activity) as ordinary townspeople. But they were not the social group that British politicians feared: in early 1774, a member of Parliament described those perpetrating such acts as the “lowest, the most idle and disorderly subjects.” As historian Barry Levy argues, many British officers and politicians saw the propensity of American colonials for tarring and feathering as evidence of a “dangerous mutation” of English identity and anxiously attempted to stamp out this threatening form of “democratic despotism” before it reached the British Isles. The slippery task of determining what differentiates American from British identity is also enacted in visual terms in Sayer & Bennett’s print: while its engraver has delineated the edges of their masks at their jawlines, in other areas—such as around the eyes of the figures in the foreground—there seems to be an elision of mask and skin, exterior and interior. Are these masks that the figures wear, or do they reveal Americans’ true characters? And what if this rebellious ritual proved to be not just a temporary carnivalesque release but the harbinger of a more permanent overthrow?

Such worries filled English newspapers as 1774 drew to a close. Earlier in the year, Parliament had passed a series of five laws designed to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party. Based on the concept of collective responsibility, these Coercive Acts—which included the bill that closed Boston’s port until its colony repaid the debt for the destruction of the tea—were intended to bring the North Americans to heel. Instead, the severity of the legislation startled many colonists and spurred early efforts at colonial unification, culminating in the first meeting of the Continental Congress. Not only did serious political discourse increase in the wake of the Boston Port Bill, but so did public acts of protest carried out in American streets and homes. Between November 1774 and March 1775, Sayer & Bennett issued four additional mezzotints representing acts of American rebellion; in this series, Bostonians beg for assistance from neighboring colonies (fig. 5), barbers refuse to shave British naval officers in New York (fig. 6), merchants are coerced into signing non-importation agreements in Virginia (fig. 7), and women boycott tea in North Carolina (fig. 8). Taken together, these five prints—linked by the addition of a plate number at the lower left of each—visualized the threatening power of colonial unity.

Under Pressure

In October 1774, Tarring & Feathering had addressed itself to Parliamentary politics. But as 1775 dawned, its interpretation quickly shifted. As incidents of tarring and feathering in America increased following the Coercive Acts, Malcom’s specific history faded. Instead, the scene came to represent not a particular act of tarring and feathering, but a symbol of the practice as a whole. From a purely practical standpoint, it made good business sense to sell a print whose design was malleable enough to support a variety of interpretations, as it increased the number of potential buyers. Over the course of ten years, Tarring & Feathering was sold from London to southern England, and even Philadelphia by 1776, leading Sayer & Bennett to produce approximately 800 impressions of the print. This is an astounding figure, given that the textured surfaces of its plate were not intended for high-volume print runs.

The study of any engraving demands that we consider not just the present object—a single impression—but the more foundational absent object: the matrix (a copper plate in this case) from which the prints were pulled. Sayer & Bennett’s firm specialized in publishing mezzotints (or “half-tones”), a medium that uses variations of texture to model forms, instead of the incised lines that create etchings or engravings. To sculpt designs out of light and shadow on a sheet of highly polished copper, an engraver would begin by creating a roughened texture of small pits to catch and hold ink across its surface. Next, he or she would create degrees of tonal variation by scraping off the rough points and burnishing smooth the indentations. One advantage of mezzotints lay in their comparatively rapid production and the resulting lack of expense. However, the medium has one significant drawback: it is not suited for heavy use, as the fragile surface of its copper plate exists in a continual state of flux. As the plate is repeatedly pulled through a printing press, its rough texture gradually abrades and loses its ability to hold ink. Therefore, each impression is less crisply defined than the previous one, as all fine details fade toward a faint, irretrievable ghostliness.

An examination of an impression from the fourth state of Tarring & Feathering reveals this process in action. William Gilpin, an eighteenth-century print connoisseur, estimated that one could print 500 good impressions from an engraved plate, while an etched plate would give about 200. He then emphatically stated, “you cannot well cast off more than a hundred good impressions from a mezzotint plate. And yet by constantly repairing it, it may be made to give four or five hundred with tolerable strength” (emphasis added). Based on Gilpin’s figures, an impression of Tarring & Feathering in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art likely numbered between the 400th and 500th impression to be pulled (fig. 9). At some point in the history of the plate’s wear, an engraver used a needle to etch additional lines into the copper’s soft surface to attempt to reconstruct facial features and separate layered forms, such as dividing hat brims from faces or knees from ships (fig. 10). But when compared with the many variations of light and shadow that model the earlier state of the print, we see the image dissolving before our eyes (fig. 11). The figures of the Americans on the ship in the background have literally faded out of the picture, while the separations between masks and skin have worn away, so that the masks worn by the foreground figures in the first state have become their permanent expressions.

To juxtapose multiple impressions is, in effect, to materialize time, insofar as its passage is marked on the plate through the effects of wear and rework. But while Sayer & Bennett’s colleagues disparaged this worn impression, it provides a critically important material record both of the print’s popularity and the pressures of running a profitable publishing business. Simply put, their firm continued to print from this worn plate because consumers would purchase its impressions in spite of their poor quality. In other words, the demand for this image of tarring and feathering must have dramatically exceeded the potential supply to have encouraged this treatment of the printing plate. As Sayer & Bennett’s print linked the personal to the professional and weathered the pressures of politics and profits, the figures in Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man, or Tarring & Feathering came to represent an ongoing threat of loss and displacement for both their publisher and their viewers.