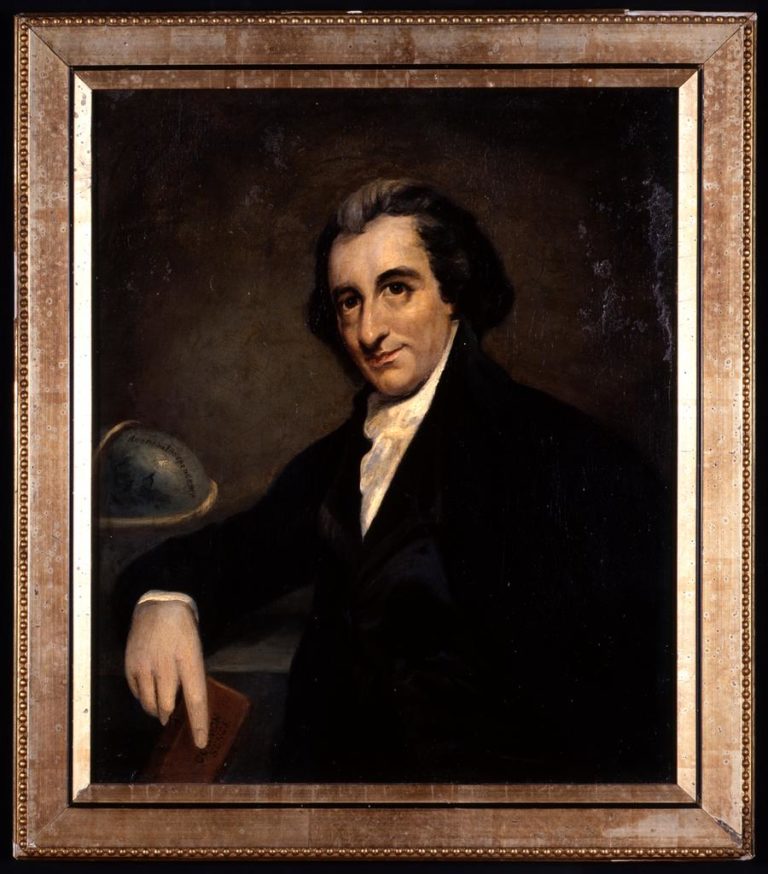

Introduction: Making Sense of Thomas Paine

Never one to shy away from controversy, Thomas Paine stood at the center of the sweeping political, social, and cultural transformations that historians have since dubbed the Age of Revolution. Although he is best known for championing American independence, he also took part in the French Revolution and supported radical political and social reform in Britain. Even a short list of Paine’s titles provides a primer on the convulsions that racked the long eighteenth century: Common Sense and the American Crisis sought to define the American Revolution as it unfolded. Rights of Man defended the egalitarian trajectory of the French Revolution. The Age of Reason challenged religious dogma and exposed clerical hypocrisy. Agrarian Justice took aim at entrenched economic inequality. But Paine was no armchair polemicist: he served in the Continental Army; campaigned for Pennsylvania’s radical constitution and for a centralized monetary policy; narrowly escaped arrest in England when he called for a constitutional convention to establish a British republic; and was elected to revolutionary France’s National Convention and then, during the Terror, imprisoned for serving in it. In fact, one of the things that set Paine apart from the United States’ other founders, who struggled to maintain the republican posture of disinterestedness, was the seamless fusion of his printed words, his public persona, and his private character.

For better or worse, Thomas Paine was indistinguishable from his distinctive, impassioned prose, at least in the eyes of the reading public. And anyone who has ever read Paine alongside his eighteenth-century contemporaries can attest that his prose was indeed distinctive. As the literary historian Edward Larkin has observed, Paine created a language of vernacular politics, an “idiom where politics could be simultaneously popular and thoroughly reasoned.” In so doing, he invited people far removed from traditional power centers into engagement and activism. To read Paine’s democratic rhetoric is to enter a “fusion of form and content writ large,” in Larkin’s terms.

That fusion of form and content may be one reason why Paine’s words have served as a lightening rod for admirers and detractors from the eighteenth century to today. But if Paine’s work continues to signify, it does not necessarily signify in the same way. Context is everything. If Common Sense has been enshrined in the American canon almost since it was published, other essays have moved in and out of American readers’ view. And if Paine’s brand of radicalism helped mark the ideological dividing line between Republicans and Federalists in the 1790s and 1800s, his words have more recently been appropriated by politicians from across the political spectrum: presidents Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Barack Obama have benefited from Paine’s ability to turn a phrase.

The three historians featured here help us understand why Paine mattered—and who he mattered to—by situating his writing in multiple historic and geographic contexts. Jason Opal rereads Common Sense with an eye toward British atrocities in eighteenth-century India. Matteo Battistini explains why Paine’s stance on monetary policy in the 1790s mattered to a Jacksonian labor radical. Finally, Nathalie Caron traces Paine’s presence in contemporary debates sparked by “the new atheism” on both sides of the Atlantic. While these essays commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of Paine’s death, they also testify to the enduring power that words—the right words—can wield.

Further Reading:

Edward Larkin’s insightful discussion of Paine’s writing can be found in his Thomas Paine and the Literature of the Revolution (Cambridge, 2005). Readers interested in tracing Americans’ varied responses to Paine should consult Harvey J. Kaye, Thomas Paine and the Promise of America (New York, 2005).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.4 (July, 2009).

Catherine E. Kelly is editor of Common-place.