Introduction: Toward a Pacific World

Discovery, exploration, conquest. Settlers, pilgrims, natives. Colonies, plantations, empires. These are the terms we associate with the beginnings of American history. They bring to mind those early “plantations,” as the English called them: Jamestown, Plymouth Colony, the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In these fragile settlements, we are often taught, English men and women planted the seeds of what would become the United States. They discovered new lands; they explored seas and rivers and backcountry; they conquered, they settled, and then they made a nation.

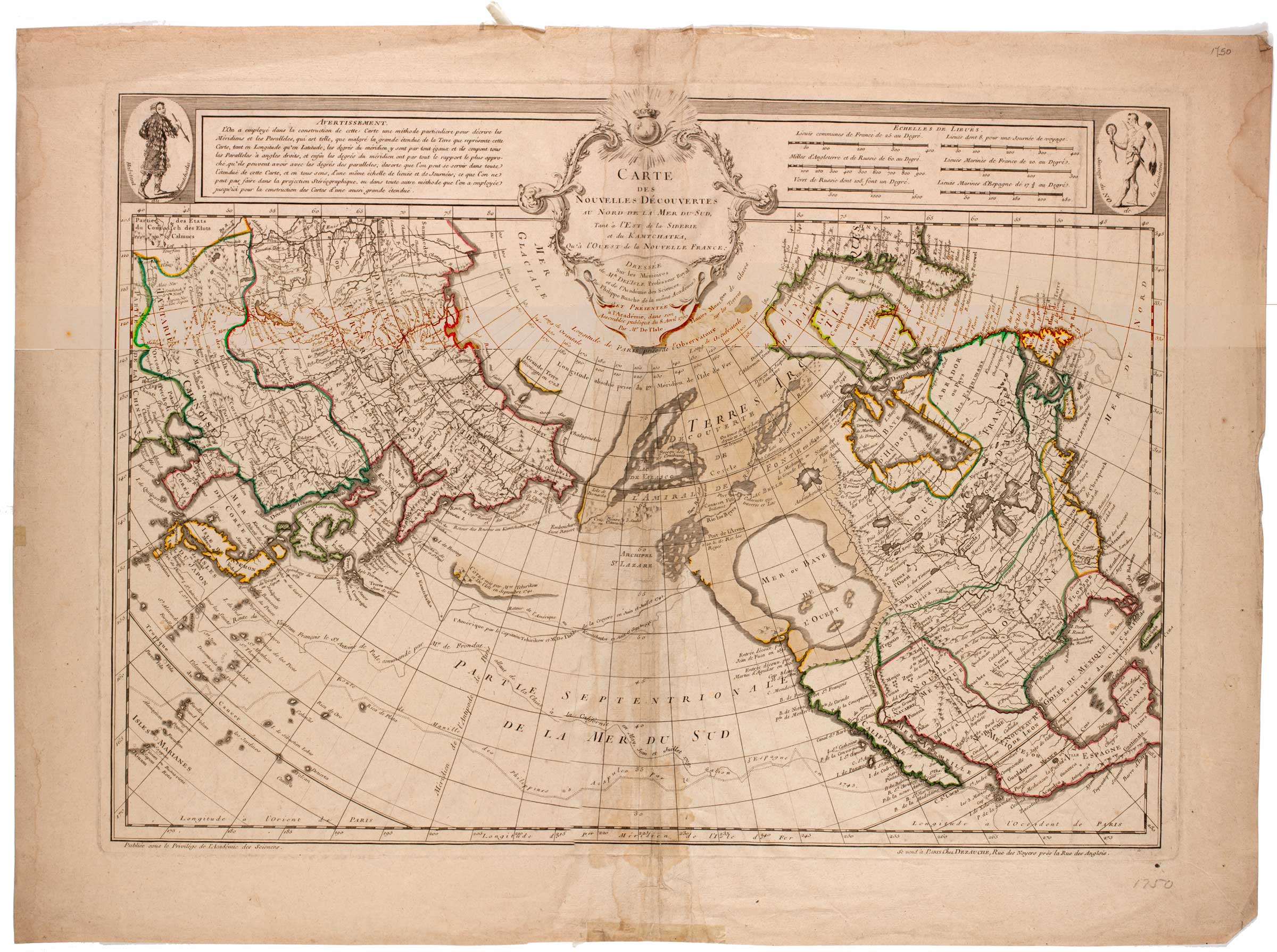

How curious it is, for those of us reared on these old maxims of U.S. history, to contemplate parts of the present-day United States—the West Coast, Hawaii, and Alaska—where the story of our national origins is much less familiar. Approached from the Pacific (which, as Mark Peterson’s essay tells us, has not always been just the Pacific), our past has an unfamiliar cast of characters. There is no clear, dominant settler population and no distinct class of mariners maintaining communication with the so-called Old World. There are no familiar Native American heroes—no Squanto or Pocahontas—and there are no harassed religious pilgrims, fleeing the corruptions of the Old World for the promise of the New. There are swashbuckling Renaissance men: Sir Francis Drake, Thomas Cavendish, Magellan, and others. But at least in the case of the Englishmen Cavendish and Drake, they tend to be better known for their Atlantic exploits than their late-sixteenth-century voyages across the Pacific.

The cast of characters who populate Pacific history includes Russian fur traders, Spanish missionaries, Japanese fishermen, French and Spanish explorers, British naval officers, American travelers, German naturalists, Tahitian translators, Aleutian hunters, Polynesian navigators, Yankee merchants, and that peculiar species of Pacific go-between, the beachcomber. Some traveled in huge treasure ships. Some rode in small seal-skin kayaks, others in grand outrigger canoes. And still others traveled overland along the coastal regions that form a massive arc from Cape Horn north to the Bering Strait and then south again toward China. Their purposes were as varied as their methods of travel. Some came seeking knowledge, others to settle new lands, some in search of game, and some to trade. Their routes were also widely varied. Some came across the vast middle of the Pacific, traveling between the Philippines and Mexico. Some traveled the Polynesian archipelago as if it was all one giant landmass. Others sailed from the Atlantic through the treacherous waters around Cape Horn. Some crossed the Bering Strait or hopscotched across the Aleutian Island chain and still others came from the Indian Ocean and the East China Sea.

These travelers did not come in one, continuous wave. Their journeys are separated by years and, in some cases, millennia. And, unlike the more familiar characters in the story of America’s beginnings, these travelers often ended their travels where they began them. How different from the Pilgrims of Plymouth or many of the young gentlemen of Jamestown.

For all these differences from the stories and characters who populate the well known ground of America’s early history, there are striking parallels. As we have learned in recent years, the history of the earliest European settlements in America can no longer be told as the history of small, isolated bands of desperate women and men, struggling against nature and themselves to survive. These European colonizers, their servants and slaves, and the Indians with whom they came into contact were in fact drawn into processes that far transcended their tiny American settlements. Those processes—including the movement of goods, of disease, of biota, of cultures, of free and unfree people—drew together a diverse array of people from throughout the Atlantic basin.

Over the previous two decades, scholars have begun to focus on this remarkable Atlantic World as a discreet area of study. And they have found that in the age of sail, oceans often did more to unite than to separate. They have also raised important questions about the tendency to divide people according to readily identified nations—with clear boundaries and distinct governments. For the people of the early Atlantic World, we now know, such divisions were often arbitrary. What those people did, where they traveled, with whom they did business, against whom they waged war—all often had little at all to do with the conventions of political geography. Who they were was as often a function of what language they spoke or how they made their living as it was of the government that ostensibly ruled them.

This sort of insight proves especially valuable when we approach Pacific history. There we find few of the nation-states that once defined European and American history. To be sure, some of the players in the Pacific sailed under European flags, but until the late eighteenth century few of them made any serious claim to territory abutting the Pacific. Relative to the Atlantic, then, the European presence there was paltry in every way. But it is precisely this fact that makes Atlantic studies so useful for understanding Pacific history. If we continue to move beyond nations and states as the defining subjects of historical understanding, turning instead to large scale processes, we can begin to see in Pacific history a vital analog to the much better known history of the Atlantic. As the essays in this issue of Common-place make clear, disease, migration, trade, and war effected the Pacific in much the way they effected the Atlantic: they drew together vast, diverse collections of human beings, whether stretching from Easter Island west to New Zealand, or from coastal California north and then west to the Kamchatka Peninsula.

For those of us interested in the early history of the United States, these Pacific communities may not be as well known or as influential as their Atlantic counterparts, but their stories still have much to teach us. At the very least, they invite us to contemplate exactly what American history is and where it began. Hence, the double entendreof this issue’s title: Pacific Routes. The stories told here deal as much with historical roots as they do the routes their subjects traveled. And we invite readers to carry this sense with them, as they make their way into the lives and stories of the Pacific.

This article originally appeared in issue 5.2 (January, 2005).

Edward G. Gray teaches early American history at Florida State University and is writing a biography of John Ledyard.

Alan Taylor teaches early American history at the University of California at Davis. He is the author of American Colonies: The Settlement of North America (New York, 2001), William Cooper’s Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic (New York, 1995), and Liberty-Men and Great Proprietors: The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier (Chapel Hill, 1990).