John James Audubon, the American “Hunter-Naturalist”: A New Species of Scientist for the New Nation

When John James Audubon died, in 1851, he had many admirers, but probably none more ardent than a Kentucky-born adventurer and author named Charles Wilkins Webber. Soon after Audubon’s death, Webber published a decidedly energetic description about first encountering Audubon on a canal boat in late 1843, when the aging naturalist was returning from a trip out West to study wildlife. As soon as Webber boarded the boat, he “heard above the buzz the name of Audubon spoken.” Apparently already familiar with Audubon’s reputation, Webber wrote that “there was one NAME that had so filled my life, that it alone would have been sufficient to inspire me.”

Audubon! Audubon! Delightful name! Ah, do I not remember well the hold it took upon my young imagination when I heard the fragmented rumor from afar, that there was a strange man aboard then, who lived in the wilderness with only his dog and gun, and did nothing by day, but follow up the birds; watching every thing they might do; keeping in sight of them all the time, wherever they went, while light lasted; then sleeping beneath the tree where they perched, to be up again to follow them again with the dawn, until he knew every habit and way that belonged to them.

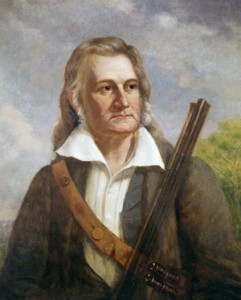

And so Webber went on for a dozen exuberant pages, describing Audubon’s “fine, classic head” and “patriarchal beard” and “hawk-like eyes,” asserting that “the very hem of his garments—of that rusty and faded green blanket, ought to be sacred to all devotees of science.” Webber finally concluding in almost breathless satisfaction, “Thus it was I came first to meet him, laurelled and grey, my highest ideal of the Hunter-Naturalist,—the old Audubon!” (fig. 2)

To a modern reader, Webber’s passionate praise might seem like a bit of excessive adulation for a man whose fame came, after all, from studying and painting birds: on the scale of outdoor activities, ornithology is not normally ranked as an especially dangerous endeavor, nor are artists typically depicted as rugged adventurers. But Webber’s eulogy reflected its context—the American West in the middle of the nineteenth century—which, for Webber, could hardly have been an unconscious or coincidental choice. Writing at a time when talk of Manifest Destiny filled the political air—when the United States had just been pushing against the Oregon border in a battle of menacing words with Great Britain and had just taken a vast expanse of land, from Texas to California, in a true shooting war with Mexico—Webber depicted Audubon as a man of the West, returning from a trip up the Missouri River after retracing part of the path of Lewis and Clark. Like those two explorers four decades earlier, Audubon expressed the expansionist reach of American science. Much more than a master of ornithology or avian art, he embodied the “hero of the ideal,” an unapologetically masculine embodiment of the “pioneer” American naturalist. In Webber’s wide-eyed assessment, Audubon became the living image of the connection between natural history and national history.

But Webber did not stop simply with this strenuous celebration of Audubon. In creating this image of the “Hunter-Naturalist,” Webber set Audubon against another sort of scientist, what he derided as the formulaic, effete, and implicitly feminine European naturalists, who, as Susan Branson has shown elsewhere in this issue of Common-place, had long been mocked as “Macaroni” (fig. 3). Too many “scientific pedants in silk stockings” and “pur-blind Professors,” Webber complained, had “technicalised” the study of nature “into what may almost be called a perfect whalebone state of sapless system … so heavily overlaid by the dry bones of Linnaean nomenclature as to become a veritable Golgotha of Science.” Given the taxonomic complexity those “pedants in silk stockings” had imposed on nature, he insisted, ordinary people had become isolated from science, “repulsed, in dismay of its formidable hieroglyphics, from what is to them as a sealed book.” By contrast, “Our glorious Audubon,” the Hunter-Naturalist of the new nation, “lived and wrote like one of the people,” and he thus represented a distinctly American—and masculine—approach to natural history, a two-way relationship between the rugged naturalist of the still-wild American landscape and the ordinary folk of the new nation. Therefore, Webber declared, “we love and venerate him passed away.”

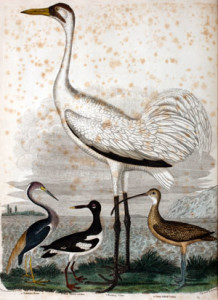

Long before Webber’s energetic eulogy, of course, Audubon had already become the early republic’s first true celebrity scientist, a self-promoting showman, perhaps, but also a remarkably skilled ornithologist and artist, a man whose work could be both scientifically accurate and emotionally engaging at the same time. He is most famous, of course, for his monumental (and now exceedingly valuable) mega-book, the four-volume compendium of 435 engraved plates, The Birds of America (1827-1838). He is a little less known for the companion book, the five-volume Ornithological Biography (1831-1839),a series of essays about ornithology, to be sure, but also about American places and people and, quite often, about Audubon himself. In fact, those self-portraits in prose can be as evocative as the several portraits of Audubon in paint; taken together, as we shall see, they reveal a pattern of personal self-fashioning that had been evident in Audubon’s life long before Charles Wilkins Webber ever met him.

As a twenty-first-century historian, I can’t allow myself to “love and venerate” Audubon as openly as Webber did, but I do find him an elusive but illustrative figure, frustrating but always fascinating. For the sake of this essay, I think Audubon bears investigation on two interrelated levels. First, because he was so self-consciously someone who defined himself by his achievements in science as much as art, he gives us a good focus for looking at an emerging American approach to natural history in his era. In Audubon’s America—essentially the first half of the nineteenth century—ornithology and other branches of natural history lay embedded in a trans-Atlantic scientific discourse that had long engaged students on both sides of the ocean. No matter how much natural historians in the early American republic might have tried to declare their scientific independence from their European predecessors, sometimes engaging in competitive and petty disparagement of those whom Webber would call the “scientific pedants in silk stockings,” the Americans’ very ability to work as nineteenth-century naturalists rested on the foundations that had been in place for at least two centuries. Indeed, Audubon worked (and frequently quarreled) with gentlemen of science of the both sides of the ocean, and he put great stock in his status in the scientific community: the engraved images in The Birds of America always carried the initials FRS and FLS—Fellow of the Royal Society, Fellow of the Linnaean Society—right after his name.

But beyond establishing his personal credentials, Audubon played a critical role in helping establish those of American science. As much as he drew attention to himself as an artist and man of science—and he did so ceaselessly and shamelessly—he also drew the attention of the American people to the richness and diversity of nature in America, helping them see it in national as well as environmental terms. Much like Thomas Jefferson a generation earlier, Audubon sought to declare America’s scientific independence from the Buffonian insistence on the inferiority of American species. In The Birds of America, Audubon offered a dramatic celebration of the new nation’s avian species, and in doing so he engaged in an act of scientific possession. He did not simply present his birds as stiff specimens for close ornithological examination; he gave them life and location, creating engaging images embedded in the American landscape. “The Birds of America” implicitly meant “The Birds of the United States.” Audubon never used the term “Manifest Destiny”—a term that entered the American political lexicon in 1845, when Audubon was well past his writing prime—but he stood squarely at the intersection of art and science at a time when natural history became entwined with national history. He was much more than a passive spectator in that process: in the first half of the nineteenth century, no one in the world of American art or science did more to stimulate a national conversation about nature in the United States.

In that regard, Audubon also embodied another important notion: that the American scientific community was by no means an entirely enclosed community, nor could it claim isolation from the rest of society. In Audubon’s America, science had not yet become subdivided into academic disciplines and institutionalized in university departments. Indeed, the study of natural history in academic repositories seemed only a far-distant second to the dramatic discoveries still available in a largely uncatalogued continent. Thomas Nuttall, Audubon’s fellow natural historian and eventual ornithological ally, perhaps best expressed the contrast. He fidgeted with frustration while holding position of curator of the botanic garden at Harvard, describing his experience there as “vegetating” among the plant collections. As soon as he had a chance, he headed west with the Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth expedition of 1834, going all the way to the Pacific Northwest and then on to Hawai’i, collecting specimens all the way. In fact, he became memorialized in Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast as “Old Curious,” the naturalist who walked along the beach “in a sailors’ pea jacket, with a wide straw hat, and barefooted, with his trousers rolled up to his knees, picking up stones and shells.” The real sailors considered him eccentric in his commitment to collecting, but in his appearance, if not his behavior, he blended in among them.

What Nuttall did implicitly, Audubon did much more explicitly, making clear the connections between the American natural historian and ordinary people and, above all, their reciprocal relationship in exchanging knowledge about the natural world. In Audubon’s America, the study of natural history remained within the reach of almost everyone, and Audubon acknowledged that as he addressed his reader in the opening pages of Ornithological Biography: “I am convinced that you love nature—that you admire and study her. Every individual, possessed of a sound heart, listens with delight to the love-notes of the woodland warblers. He never casts a glance upon their lovely forms without proposing to himself questions respecting them.” Studying nature and proposing questions about what one sees, of course, form the basic tasks of the natural historian. Particularly in the era of the early republic, at a time when the answers to many questions of natural history still remained unanswered and when many parts of the continent still remained relatively unexamined by naturalists, Audubon recognized that the observant amateur could see just as much as he could. To get answers to various questions about bird identification, migration, and such, he invited his reader to take part in the investigation, and the questions recur frequently throughout Audubon’s writings—”Can you, reader, solve the question?”; “Reader, is this instinct or reason?”; “Reader, can you assist me?” By the same token, Audubon created a bond of imagined companionship in the wild—”Reader, many times have I wished that you and I were in it”—and called to the reader to “make up your mind, shoulder your gun, muster all your spirits” and go into the “interesting unknown.”

Today, his occasional admissions of ornithological ignorance and his repeated reaching out to the reader for help may seem little more than an act of authorial artifice, perhaps even a disingenuous literary device for subtly asserting Audubon’s own authority by raising questions he knew most readers could not answer, or by posing challenges he knew most readers could not take. In reading Audubon, it always makes sense to take a careful, even skeptical, view of his self-conscious construction of his role as a naturalist: whenever he seems to be talking to the reader, he is most often talking about himself. But at the same time, he is talking about himself within a particular historical and cultural context. Like his counterparts in the political arena of the early republic, Audubon embraced and often celebrated his reciprocal relationship with the common people. In doing so, he popularized and enhanced the standing of natural history—and therefore his own standing—in the new nation that celebrated the image of the “common man” as a political and cultural icon. He would become a similar icon of his own sort.

Consider, for instance, the various portraits we have of Audubon in his heyday. Throughout his life, he perfected his persona as the wilderness artist, the long-haired, buckskin-clad, gun-toting naturalist, even on the far side of the Atlantic. Audubon took up temporary residence in Great Britain (first Scotland, then England) in 1826-27, beginning work on The Birds of America in earnest. Soon after he arrived in Great Britain, he sat to be painted himself, and to be painted not as an artist, but as a woodsman—or, as he would soon come to call himself, the “American Woodsman” (fig. 4).

He wrote his wife, Lucy, who was still living back in the United States, that he was “now a strange looking figure with gun, strap and buckles, and eyes that to me are more those of an enraged eagle than mine.” Being in Great Britain, in fact, made him even more aware of his American identity as a man of the woods, underscoring his “sense of recollection” of his place in the world: “[nothing] could make me relinquish the idea that in my universe of America, the deer runs free, and the Hunter as free forever.—No—America will always be my land. I never close my eyes without travelling thousands of miles along our noble steams and traversing our noble forests.” As he became increasingly well-known in artistic and scientific circles in the Atlantic world, he became increasingly committed to his embrace of America as his “universe,” and to his self-styled image of himself as the “hunter … free forever” (figs. 5, 6, 7)

Audubon was not by any means the first American to adopt an especially woodsy-looking aura when he went to the far side of the Atlantic—we think, of course, of the fur-hatted Franklin in Paris in 1784—and Audubon’s aquiline image, with gun, strap, and buckles, might be seen as only playing to type (fig. 8).

But for Audubon, costume spoke to character, even when he lived in an urban environment; the elements that became constants in his many portraits—wearing the garb of a man of the woods, displaying a gun as the critical tool of his trade, locating himself in the American outdoors—defined the self-conscious core of his artistic and scientific identity.

His approach to both art and science rested on one central premise: he drew the birds well because he knew the birds well. Knowing the birds, of course, meant tracking them in the environment they inhabited, and that meant going into many dark, dangerous, and uncharted places:

Many times, when I had laid myself down in the deepest recesses of the western forests, have I been suddenly awakened by the apparition of dismal prospects that have presented themselves to my mind. … At other times the Red Indian, erect and bold, tortured my ears with horrible yells, and threatened to put an end to my existence; or white-skinned murderers aimed their rifles at me. Snakes, loathsome and venomous, entwined my limbs, while vultures, lean and ravenous, looked on with impatience. Once, too, I dreamed, when asleep on a sand-bar on one of the Florida Keys, that a huge shark had me in his jaws, and was dragging me into the deep.

In this one passage Audubon conjures up many of the standard menacing images that recurred in the long-standard literary descriptions of the American wilderness—dark forests, deadly quicksand, howling Indians, murderous backwoodsmen, loathsome snakes, ravenous vultures, even a shark thrown in for special effect—that modern readers might now consider a cliché. But he created this compendium of wilderness terrors not so much to evoke a nightmarish vision of nature. Rather, he listed the rigors of the naturalist’s life to impress upon the reader that there could be no other scientifically legitimate way to know nature: “[H]ow difficult must it be,” Audubon wrote, “for a ‘closet naturalist’ to ascertain the true distinctions of these birds, when, having no better samples of the species than some dried skins, perhaps mangled, and certainly distorted, with shriveled bills and withered feet.” Whatever the distinction between birds themselves, the distinction between students of birds seemed clear: relying on the dried and withered specimens of fellow collectors, the “closet naturalist” would never come close to the fresh specimens an outdoor ornithologist could have at hand. Audubon always took care to assure us that he, Audubon the ornithologist, Audubon the artist, would pursue his calling with courage and face nature in its wildest form.

In that regard, Audubon was by no means altogether unique. Throughout the early years of the nineteenth century, the work of the American naturalist had become increasingly associated with the image of risk-taking manliness that Audubon eventually embodied. The image began perhaps most explicitly with Alexander Wilson (1766-1813), the man who gained the coveted, albeit occasionally disputed, title of “Father of American Ornithology” some years before Audubon became famous. Beginning in 1808, Wilson published the first volumes of American Ornithology (1808-1814), the nine-volume collection of bird paintings and descriptions that defined the field until Audubon began producing The Birds of America over two decades later.

Wilson and Audubon famously, perhaps predictably, came to be cast as scientific rivals, but their parallel approaches to describing their work are of more immediate concern here. Wilson was, like Audubon, an immigrant to the United States, having arrived in 1794 from his native Scotland, where he had worked as a weaver and then as a political activist and commercially unsuccessful poet. Soon after coming to America, Wilson made the pursuit of birds his passion for almost twenty years, and as Audubon did later, he tended to describe the American naturalist’s work in rugged-sounding terms, portraying himself as man of science struggling against the physical rigors required in research. He wrote about it to his brother in 1810: “Since February, I have slept for several weeks in the wilderness alone, in an Indian country, with my guns and my pistols in my bosom, and have found myself so reduced by sickness, as to be scarcely able to stand.”

Wilson also described almost losing his life in the pursuit of a bird, a pied oyster-catcher, when he took to the water in pursuit of it at Cape May, New Jersey (fig 9).

He had wounded the bird with his gun, and as the bird tried to escape into the ocean, he plunged in after it—only to remember, too late, that he was still “encumbered with a gun and all my shooting apparatus.” As the ebb tide started carrying him farther away from the shore, Wilson had to choose between his own survival or his escaped specimen, and, almost reluctantly, he made his way back to the beach “with considerable mortification, and the total destruction of my powder-horn.” As if to mock him, the wounded oyster-catcher rose to the surface “and swam with great buoyancy out among the breakers.” Oyster-catchers are not especially menacing birds (except to oysters), but for Wilson, it was the pursuit of the bird, the pursuit of science, that mattered, and living in the woods or diving into the ocean was the only way Wilson would have it.

In language that Charles Wilkins Webber could well appreciate decades later, Wilson also complained of the tendency among naturalists to become too technical, to spend so much time separating birds into so many “Classes, Orders, Genera, Species, and Varieties” that the resulting complexity and disagreement had “proved a source of great perplexity” to ordinary people. One of the main reasons for this confusion, Wilson continued, was the failure, or perhaps refusal, of other naturalists to observe personally “the manners of the living birds, in their unconfined state, and in their native countries.” The naturalist had to get out into nature, into the woods or even the ocean, to see the birds and do good work.

Doing good work turned into bad health for Wilson, who suffered from stress and sickness, finally dying of dysentery in 1813. In death, he received a rugged-sounding eulogy from his Philadelphia friend and ally, George Ord, that would anticipate elements of Charles Wilkins Webber’s later celebration of Audubon as the Hunter-Naturalist. Ord described Wilson as an outdoor ornithologist, certainly “no closet philosopher—exchanging the frock of activity for the night-gown and slippers.” Wilson’s knowledge, Ord explained, came not from reading books about nature, “which err,” but from engaging nature itself, “which is infallible.” Though hardly as excessively strident or as aggressively masculine as Webber’s later praise for Audubon, Ord’s celebration of Wilson drew on some of the same elements—in this case, the contrast between the woodsman’s “frock of activity” and the more effeminate-sounding “night-gown and slippers,” between knowledge derived from the “unwearied research amongst forests, swamps, and morasses,” and the precious little one could learn in the library. Ord never devised a phrase quite as evocative as Webber’s “Hunter-Naturalist,” but it would have fit his depiction of Wilson quite well. As it was, Ord shared with Audubon a dismissive term for the other sort of naturalist, the much-despised “closet philosopher” or “closet-naturalist.”

No one pursued birds or science or, above all, the image of the manly naturalist more effectively or aggressively than Audubon himself. Never to be outdone by his ornithological rival Wilson, he told his own tale about pursuing a great horned owl so far into a swamp that he got “sunk in quicksand up to my armpits,” only to be rescued at the last minute by his companions. The story may or may not have been exactly accurate—many of his tales tended to be self-serving embellishments on the truth—but it had a purpose: “I have related this occurrence to you, kind reader,—and it is only one out of many—to shew you that every student of nature must encounter some difficulties in obtaining the objects of his research, although these difficulties are little thought of when he has succeeded.”

Audubon defined ornithology as manly work, and he liked to locate himself in the world of men, particularly the rugged hunters of the American frontier. Indeed, Audubon had his own story about how he once “happened to spend a night … under the same roof” with that true icon of frontier masculinity, Daniel Boone. “We had returned from a shooting excursion,” Audubon began, rather casually putting himself in company with Boone in the outdoors. Like a star-struck fan of a famous athlete, Audubon gushed not only about his hero’s skills with a gun, but about his physique: “The stature and general appearance of this wanderer of the western forests approached the gigantic. His chest was broad and prominent; his muscular powers displayed themselves in every limb; his countenance gave indication of his great courage, enterprise, and perseverance.” Boone declined to sleep in a bed, Audubon said, but “merely took off his hunting shirt, and arranged a few folds of blankets on the floor, choosing to lie there than on the softest bed.” And so the two men bedded down for the night—Audubon presumably in a bed, but Boone shirtless and on the floor—before resuming the hunt the following day.

Audubon’s Boone story was a good one, to be sure, but it was also a complete fiction: it never happened. Audubon did once write to Boone and ask to go hunting with him, in 1813, but Boone turned him down. Audubon was in his late twenties then, but Boone was almost eighty, and almost blind. They did not have a hunting date, but that never stopped Audubon from writing about one. And that underscores an important point: to read Audubon for the absolute truth is to miss his larger meaning. Audubon’s agenda, rather, was to create an effect—or an affectation—the image of the naturalist as a “wanderer of the western forests,” just as bold as Daniel Boone. If going shooting with Daniel Boone would make the point in print, then the story would work well enough.

Audubon tells one equally evocative tale in paint, in this case the Golden Eagle (fig. 10). We can deconstruct the image easily enough: the eagle rising into the sky above a rugged, mountainous landscape, crying out as it clutches a bloodied rabbit in its talons, the powerful predator with its now-deceased prey. And below, down on the log over the precipice, creeping along with a hatchet, a gun and a bird (probably a golden eagle) strapped to his back, we see the hunter-naturalist (probably a self-portrait of Audubon himself), vulnerable but brave, taking a risk in the wilderness, giving his all for ornithology (fig. 11).

The true story, however, is that Audubon didn’t capture the eagle in the wild, didn’t crawl over the precipice with his specimen. He bought it from a friend in Boston, a bird in a cage that cost fourteen dollars. Then he took it back to his hotel room, kept it in the cage for three days, and tried to kill it by covering the cage closely with a blanket, putting a pan of burning charcoal in the room, closing the door and windows tightly, and waiting for the eagle to die. It didn’t work. After a few hours, Audubon writes, he “opened the door, raised the blankets, and peeped under them amidst a mass of suffocating fumes.” There the eagle still stood, Audubon continues, “with his bright unflinching eye turned towards me, and as lively and vigorous as ever!” The next morning, to make the fumes even more toxic, Audubon added some sulfur to the smoldering charcoal, making the indoor environment a small-scale version of Hell itself, but again “the noble bird continued to stand erect, and to look defiance at us whenever we approached his post of martyrdom.” Finally, to finish off the defiant bird and to make the martyrdom complete, Audubon “thrust a long pointed piece of steel through his heart, when my proud prisoner instantly fell dead, without even ruffling a feather.”

It’s a bizarre story, something Poe might write if he were to venture into ornithological Gothic. But again, it’s not so much the accuracy of the written narrative that matters, at least not to Audubon. It’s the accuracy of the art and the accuracy of the science that matter, and the embellishments of the painting serve another purpose: to underscore the rigors of scientific research, the manly work of the American Woodsman.

In that regard, I want to close by trying to be fair to Audubon. No matter how often he might have stretched the truth about his own exploits and pulled the reader’s leg, either in print or in paint—and he did that much of the time—he came much closer to the truth when he turned to birds. He valued his status as a naturalist, and he craved credibility in the scientific community. Although his descriptions of birds could contain lively stories that a modern ornithologist might dismiss as unscientific fluff, he also took care to provide the kind of close observations about physical characteristics, habits, and habitat that still bear scientific scrutiny. The proof, of course, lay ultimately in the painting, where his detailed knowledge of birds became most evident. And no matter how he got the golden eagle, that’s a good and accurate painting of the bird.

And what about his picture of himself? Audubon was, like Alexander Wilson and Thomas Nuttall, an immigrant to the United States, and he may have posed, both in his paintings and in his own prose, as a rugged, outdoors naturalist in order to define his American-ness and underscore his sense of distance from his trans-Atlantic background. Still, it was not all pose alone. Even when taken at a discount for all their rhetorical excess, Audubon’s many tales of the rigors of art and science in America contained an element of truth, and they certainly had a larger rhetorical point: the alternative to taking risks in the name of nature, he warned, would be to risk becoming that most sedentary sort of scientist, the effete European “closet-naturalist.” It might be easy enough to rest in one’s armchair and read from a text and take the word of others, right or wrong; nothing, however, could take the place of “personal observation when it can be obtained,” of actually seeing the birds and counting the eggs, no matter what the personal challenges. To be anAmerican naturalist, then, meant taking a decidedly risky, even defiantly manly approach to the pursuit of science.

On that point, Audubon himself had unmistakably made his choice, both for his primary activity as a naturalist and for his personal identity as the “American Woodsman.” Anyone curious and courageous enough to study nature, he implied, could do the same. Perhaps more like an avuncular invitation than a chest-thumping challenge, Audubon’s direct call to the reader to get out of the chair and take to the forest still drew a clear distinction between those who would encounter nature out of doors or those would continue to sit inside and merely read about it. Facing dangers and dismal prospects of the “deepest recesses of the western forests”—hostile Indians, white-skinned murderers, snakes, vultures, and other menaces, real or imagined—defined the crucible of scientific credibility. “It is,” Audubon assured his reader, “the ‘American Woodsman’ that tells you so.”

Further reading

Audubon has always been good for the biography business. At least six Audubon biographies appeared in print in the twentieth century, the best of the lot being Francis Hobart Herrick, Audubon the Naturalist: A History of His Life and Time, 2 vols. (New York, 1917); and Alice Ford, John James Audubon: A Biography (Norman, Oklahoma, 1964; 2nd ed., New York, 1988). Earlier in this current century, three new Audubon biographies came into print: Duff Hart-Davis, Audubon’s Elephant: America’s Greatest Naturalist and the Making of The Birds of America (New York, 2004); William Souder, Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America (New York, 2004); and Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon: The Making of an American (New York, 2004). While I generally respect the research and the basic narrative of all these works, I think they sometimes become so concerned with the day-to-day developments in Audubon’s individual case that they fail to see many of the larger issues at stake. Too often, the authors go from looking at him to seeing the world through him, adopting his personal perspective and therefore losing a broader focus on the larger world he inhabited.

The history of American natural history seems to be on the rise of late. A generation or so ago, George H. Daniels’s American Science in the Age of Jackson (New York, 1968) did not even mention Audubon or Alexander Wilson, and Thomas Nuttall got only a brief biographical blurb. Thirty years later, however, an issue of the Huntington Library Quarterly, 59: 2, 3 (1998), edited by Amy R. W. Meyers and devoted to “Art and Science in America: Issues of Representation,” brought together a collection of essays on the visual presentation of American natural history, most of them based on book-length studies then in progress. Similarly, Stuffing Birds, Pressing Plants, Shaping Knowledge: Natural History in North America, 1730-1860, edited by Sue Ann Prince (Philadelphia, 2003), offered a brief but useful introduction into the field. Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2006), has quickly become a standard work for the eighteenth century, and Andrew Lewis, A Democracy of Facts: Natural History in the early republic (Philadelphia, 2011) carries the investigation into the nineteenth century. Christopher Iannini’s forthcoming Fatal Revolutions: Natural History, West Indian Slavery, and the Routes of American Literature (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2011) promises to be an important addition to the field.

This article originally appeared in issue 12.2 (January, 2012).

Gregory Nobles is a decent birder who is also professor of history at Georgia Tech, where he directs the university’s Honors Program. This essay was first presented at meetings of the British Group in Early American History (2010) and the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic (2011), and it will later be incorporated into a book, The Art and Science of John James Audubon: Bringing Nature to the Nation.