John Paul Jones, a New “Pattern” for America

In September of 1776, the Continental Navy became the first American military branch to designate an official uniform. In March of 1777 it became the first to alter it. The change originated from John Paul Jones and a small group of naval officers dissatisfied with the mandated ensemble consisting of a red-lapelled blue coat, a gold-laced waistcoat, and blue breeches. An unofficial agreement allowed American naval men to substitute a white-lined, red-lapelled blue coat and white waistcoat for the official model, and to forego blue breeches for white. The alterations, ornamented with an epaulet inscribed with a rattlesnake and “Don’t Tread on me,” Samuel Eliot Morison observes, resulted in “a much smarter uniform than the blue and red.” Perhaps the “smartest” quality of the new uniform, however, derived from the confusion it caused during engagements with the enemy. From a distance, ships populated by officers dressed in the new uniform resembled captains of the British fleet, leading John Adams to describe the uniform as “English.” Lowering the ensign, at least temporarily, added to the deception. This masquerade, embraced by Captain Jones, created a tactical advantage while at sea: the enemy saw the unmarked ship as familiar and relaxed its defenses, only to find itself unexpectedly engaged, and quite often over-matched, by a smaller, scrappier opponent.

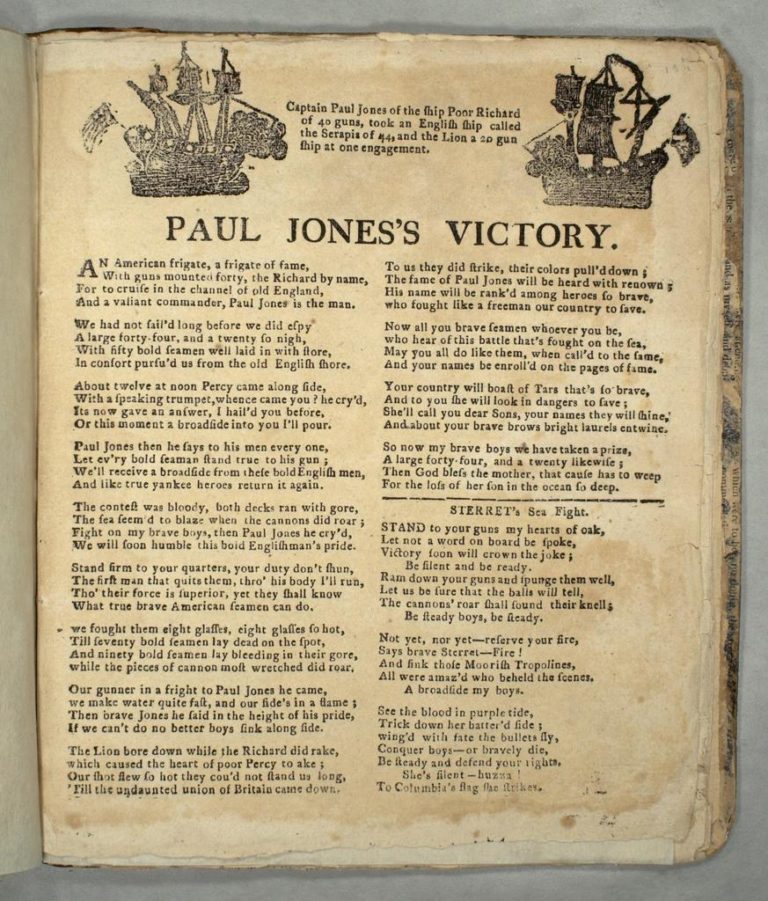

John Paul Jones was a figure who would have been familiar to most American readers in the first half of the nineteenth century as the greatest naval hero of the Revolutionary War. Lauded as the first officer to raise the Grand Union flag aboard an American warship (the Alfred, in 1775), the victor of ferocious sea battles against the British frigate Serapis and the man-of-war Drake, Jones is best known today as the originator of the oft-quoted American mantra “I have not yet begun to fight.” John Paul Jones enjoyed popular acclaim throughout the nineteenth century. No fewer than twenty-three biographies featured Jones as the subject; three editions of his writings and letters became available to the public; and fiction writers, poets, and dramatists on both sides of the Atlantic claimed Jones as their title character. In iconography Jones cut his most dashing figure—a figure he personally constructed and adorned with that costume he himself had carefully designed in 1776. After Charles Willson Peale painted his portrait four years later, and Jean-Antoine Houdon sculpted his bust in 1780-1, these depictions set the pattern for pictures of Jones for at least seventy years thereafter—with precisely the kind of commanding appearance he favored for himself. But the duplicity he had stitched into the navy’s uniform—what you saw was not what you actually got—became a motif that worked its way into an entire series of representations of Jones after his death in 1792.

Was the hero actually a bloodthirsty pirate? A rake and seducer of ladies? Indeed, a robber, a murderer, a political opportunist?

Of course, in patriotic histories of the Revolution Jones stood in for the courageous patriot, the tireless warrior in the battle for Independence. Still, Jones had lived a highly eventful life before (and after) joining the American cause, and his nineteenth-century commentators seized upon those adventures to depict certain unsavory aspects of the hero’s character. Although crewman Nathaniel Fanning understood Jones to be “a great lover of the ladies” for his practice of “carrying off” women, many nineteenth-century authors indicted Jones as a “libertine” and a “rapist,” even while they commended his patriotic service to their audience of young men. George Sinclair, as early as 1807, published a biography of Jones modeled after the 1803 London-based original with the omnibus title: The Interesting Life, Travels, Voyages, and Daring Engagements of the Celebrated and Justly Notorious Pirate, Paul Jones: Containing Numerous Anecdotes of Undaunted Courage, in the Prosecution of his Nefarious Undertakings. So was the hero actually a bloodthirsty pirate? A rake and seducer of ladies? Indeed, a robber, a murderer, a political opportunist?

For many readers (and publishers), it may have been so much the better that tales of John Paul Jones presented him as a ruthless pirate. In much of popular literature, the pirate was the “romantic outlier” rather than the feared terrorist plundering ships and port cities. Versions of pirates attractive to popular audiences emerged through such works as Byron’sCorsair; numerous popular ballads about Captain Kidd, notably, “The Dying Words of Captain Robert Kidd”; Alexandre Exquemelin’s popular history The History of the Bucaniers of America(first published in Dutch in 1678, this book offered influential accounts of the lives of seventeenth-century pirates); Charles Ellms’ frequently reprinted collection of pirate biographies, The Pirates Own Book (1837); and numerous popular songs about the piratical life.From a political standpoint, in some quarters piracy even became synonymous not with greedy banditry but with independence and the struggle against injustice. American pirate-types, like those characterized in The Florida Pirate (1823) and later in Herman Melville’s novella “Benito Cereno,” often flew the skull and crossbones only after being “denied the general consent of nations.” Moreover, in early nineteenth-century British and American novels, John Paul Jones (or men based upon the late captain) frequently dropped in on tales of mismatched love, maritime adventure, and epic romance. Among the best known examples are James Fenimore Cooper’s The Pilot, Walter Scott’s The Pirate, and Alexandre Dumas’s Captain Paul. For the inheritors of the Revolution, to use Joyce Appleby’s phrase, at least to the book-buying public, the static portrait of the stalwart patriot was often shelved in favor of the excitement of the rakish marauder.

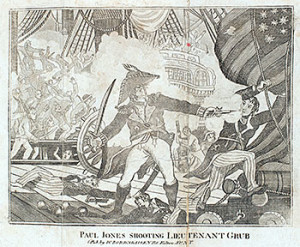

When William Borradaile reissued Sinclair’s edition of Life and Remarkable Adventures … of John Paul Jones twenty years after its first publication, he included a frontispiece illustration of Jones shooting one of his officers point-blank, even as he advertised Jones as the “celebrated” hero rather than the “celebrated and justly notorious pirate” as originally promoted by Sinclair’s title. “Paul Jones Shooting Lieutenant Grub”, Borradaile’s choice for his edition’s frontispiece, echoes the spirit of the image titled “Paul Jones shooting a sailor who had attempted to strike his colors in an engagement” (1779) found in the British original and, as a result, raised old concerns over the increasingly storied figure. While “Paul Jones Shooting Lieutenant Grub” cloaks the captain in national legitimacy as Jones and his combatants announce their shared cause through their similar uniforms, the illustration exposes the captain’s barbarism in his actions. The print not only indicts Jones of summarily executing one of his crew, but the range of the shot and the bodies below it also suggest the action to be both murderous and habitual. Jones may be remembered for raising the American colors aboard the Alfred and refusing quarter with “I have not yet begun to fight”; however, the Grub image illustrates a dark side of Jones’s fiery will and the bloodshed that sometimes ensued, in the process questioning his legitimacy as a hero.

This frontispiece illustration therefore revealed the flexibility of cultural memory and encouraged some writers to try to rehabilitate Jones’s reputation by publishing official accounts of his life authorized by the Jones estate. For although The Life and Remarkable Adventures… was sold as a sensational novel, the impression of Jones as a piratical murderer made the leap from fictional illustration to widely accepted fact, according to newspaper articles and biographical accounts, and Jones’s family wanted to “correct” that image. Historian Robert Sands, armed with a more complete set of Jones’s papers and determined to “circulate an unvarnished and full account of the rear admiral’s life,” credits the ubiquity of both the Grub print and the false testimony incited by it as his motivation for publishing the corrective Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones (1830). Sands, dissatisfied with the ever-evolving “juvenile” version of Jones’s story, producedLife and Correspondence to tidy the chronological disorder of the captain’s life found in previously circulated versions, what he calls the “inextricable confusion” created by some “capricious demon”; rectify the “fabulous” and “monstrous legends” encouraged by the popular press; and correct the biographical misrepresentation constructed by a “decidedly” British gloss.

The protagonists that emerge through the pages of antebellum fiction, however, illustrate the public’s appetite for the “active and enterprising” miscreant rather than the cleaner and perhaps more accurate version of the American hero provided by authorized biographies like Sands’. American authors working in the genre of popular romance in this period often disguised their heroes as misunderstood beggars, thieves, and pirates in order to muddle the distinction between hero and villain. Herman Melville further complicates the distinction by characterizing Jones as the “model rogue” in his novel Israel Potter, the lone “crimson thread” flitting through the “blue-jean” travails of Israel R. Potter.

Serialized in 1854-55, Israel Potter is loosely based on a pamphlet autobiography written by a Rhode Island-born veteran of the Revolutionary War who had been taken prisoner by the British and lived much of his life in exile in England. The novel appears, at first glance, to be a bad-luck story of an American boy always caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Although Israel Potter shares the field-to-battle story popularized by Israel Putnam, Potter’s Bunker Hill experience leads to capture rather than to celebrity and sends him to England in chains. Melville recounts the clumsy happenings described in the original autobiography, including Potter’s chance meetings with King George III and Benjamin Franklin (in his role as the American ambassador to France), yet the novel eventually veers away from authenticity, in both style and content, and links the fate of Potter to the various enterprises of John Paul Jones. Melville, for example, positions Israel within earshot of Jones’s famous “I have not yet begun to fight” speech, and credits him with sparking Jones’s fiery retaliation upon the port of Whitehaven, the city the captain first sailed from at age twelve. Yet Israel’s fame is short lived. His fictional service to Jones—much like his “real” life—eventually lands him aboard another British ship and keeps him on the wrong side of the Atlantic for the better part of fifty years.

Melville advertised his Revolutionary tale as an “adventure” in a letter to his editors at Putnam’s, yet the intention of the autobiographical pamphlet Life and remarkable adventures of Israel R. Potter (1824) was to secure remuneration for Potter’s military service rather than to spin a thrilling tale of intrigue. In his motley characterization, however, Melville does more than transform Potter’s story from one of hapless exile to one of unlikely celebrity as it riffs on autobiography to produce fiction. Israel Potter presents Jones, as well as the country he serves, as more rogue than Revolutionary. Melville’s Jones looks like the pirates in Exquemelin’s Bucaniers of America,dresses like the pirate suggested by the lurid frontispieces of sensational novels, and acts like the pirates cum revolutionaries of nineteenth-century American fiction, all the while advertised as the emblem of a maturing nation—as Melville writes, “America is, or may yet be, the Paul Jones of nations.” Like the confusion Jones fashioned at sea, the narrative portrait offered in Israel Potteralternates between patriot and pirate, and therefore refuses to advance a single version of the nation’s complicated history.

Of course, Melville allows neither his narrator nor Israel to actually call Jones a pirate. Israel may describe Jones’s “jaunty barbarism” and “savage” markings under his European finery, but he never truly interprets what he sees. Assumptions and hearsay, however, provoke incidental characters to associate Jones with piracy. An oddly placed maritime “quack-doctress” calls Jones a “reprobate pirate”; English sailors assume the Ranger to be “some bloodthirsty pirate” when they fail to recognize her nationality; and a British ship unknowingly solicits information from Jones about “that bloody pirate, Paul Jones.” In the last instance, Melville shows Jones, when confronted by his reputation, as a light-hearted Robin Hood rather than a despotic Captain Kidd. He encourages his enemies to arm themselves with money rather than ammunition: “So, away with ye; ye don’t want any powder and ball to give him. He wants contributions of silver, not lead. Prepare yourselves with silver, I say”—and offers a keg of pickles rather than one of powder demanded by his enemies.

Melville’s use of the term “pirate” as a charge leveled at Jones only by his enemies did revive this earlier cultural mythology of Jones in the 1850s, as most subtitles of American publications about Jones by this point had stopped using the word “pirate,” and most accounts had done away with inflammatory frontispiece illustrations. Yet not all Americans succumbed to the intoxicating memory of Paul Jones. The 1846 edition of Life and Adventures of John Paul Jones may lack a frontispiece illustration, but its preface decries the character of Jones and other revolutionary leaders even as it reprints the partially disreputable version of Jones within, announcing that “the whole race of magnificent barbarians, gorgeous tyrants, unparalleled cutthroats, and gigantic robbers … have never been able to fix our devotion.”

Melville reinforces the roguish designation of Jones as “outlaw,” as well as Israel’s initial impression of the captain, by fashioning him as more Continental aristocrat than stalwart George Washington, while at the same time marking him as recklessly uncivilized. Never does the reader of Israel Potter see the Jones of Peale’s 1781 portrait, nor do we witness the proud dignity illustrated by the many Jones prints and publications of the nineteenth century. Instead, we are given “pagan” tattoos covered by a “laced coat sleeve” and hands covered in rings and “muffled in ruffles.” The novel’s references to clothing and appearance, rather than offering a sense of period authenticity, reinforce Melville’s editorial position suggested by his tongue-in-cheek introduction, contradict the popular understanding of “homespun” through uncomplimentary characterizations of Potter and Benjamin Franklin, and certainly complicate the understanding of Jones in the nineteenth-century imagination.

Jones as the emblem of America as created though Melville’s paradoxical layering (“à-la-mode [but not] altogether civilized…”) criticizes the American practice of myth-making even as it creates a maritime frontiersman as its “Representative Man,” to use Emerson’s term. Although Melville’s Jones resembles the lonely backwoodsman of much of the frontier literature of the period, the Jones of Israel Potter appears as Indian rather than as an “Indian-fighter” like other frontiersmen. Of course, Melville’s representative American displaces Native Americans even as he assumes so-called “Indian” characteristics. By comparing Jones’s manner to “a look as of a parading Sioux demanding homage to his gewgaws” and determining the captain’s seated posture to be “like an Iroquois,” Melville prompts the reader to rely on stereotypical “stock” poses for Native Americans created by literature and then directs the reader to assign these characteristics to Paul Jones. These descriptions co-opt familiar notions of indigenous peoples to disguise the Scottish Jones in “native” legitimacy while dressed as the very English enemy he sought to destroy.

Coupled with the cultural resurrection of colonial homespun fabric, evidenced through the emergence of spinning wheels as parlor ornaments and historical decor at public events—such as Fourth of July celebrations—in the mid-nineteenth century, initiated in part by Horace Bushnell’s 1851 tribute to the “simply worthy” men and women of America’s pre-Revolutionary “Age of Homespun,” it would seem that Melville might have wanted the lasting image of Jones that readers took from his novel to emphasize Jones’s humbler attributes rather than his interest in fashionable apparel. Yet, clothing—and Jones’s interest in it—is a frequent topic of conversation. Upon their reunion aboard theRanger, Potter and Jones almost immediately digress into discussions of apparel. Paul Jones even solicits Israel’s opinion of his hat—”What do you think of my Scotch bonnet?”—overtly calling attention to Jones’s national origin, but also signaling the captain’s concern for his appearance and his alteration of the naval uniform. The sartorial packaging of Jones in Israel Potter begs the question of authorial intent. Namely, why did Melville clothe his self-professed national emblem—”the Paul Jones of nations”—in European fashion rather than joining his contemporaries and idealizing the homespun and “linsey-woolsey” of the heroes that fought the Revolution?

Melville, it would seem, uses clothing to critique the United States’ emerging national mythology through the “homespun” of Israel and the “linsey-woolsey” of Franklin, and punctuates the argument through the fashionable “savagery” of John Paul Jones. The raw portrait of the swarthy, daring Jones, therefore, becomes an ideal rather than an embarrassment for Melville’s America, a model of transparency and honesty. In Israel Potter Jones can no sooner hide his “savage” tattoos than camouflage the absence of rings from his hand. Try as he might, Melville’s Jones can never transcend his true identity by dressing in European finery. In spite of his sartorial extravagance, or rather because of it, Jones becomes the icon of America which—like Jones, Melville insists—must admit its failings despite the prevailing trends in national mythology. America in the mid-nineteenth century may have been trying to fashion an identity for itself based on the Yankee ideal popularized by Benjamin Franklin, and to identify itself as a pioneering nation rooted in characters ranging from Cooper’s frontiersman Natty Bumppo to the 1856 Whig candidate for president John C. Frémont, whose campaign identified him as “The Pathfinder.” From Melville’s more jaundiced perspective, however, such posturing in the 1850s was a ruse, and America (having just seized California and much of the Southwest from Mexico) was more a pirate than a pioneer.

John Paul Jones duped the British by disguising his identity in enemy colors. Melville’s counterfeit deceives the “skimmer of pages” who, in trusting the authenticity of the historical reprint, believes the character of Jones created in Israel Potter to be a “true blue” copy of the man lionized by American memory. It is not. The alternate “crimson thread” spun by Melville challenges the portrait of Captain Jones and, by extension, American identity. America in Israel Potter is no different from the gardener’s son who surreptitiously finds himself leading a navy. Rather than American Exceptionalism and the “city upon the hill” motif put forward by John Winthrop aboard the Arbella, Melville emphasizes the reliance upon chance for the nation’s success, and he refashions the accepted standard of the “pattern American” through his endorsement of the “unprincipled” and “reckless” John Paul Jones. Melville’s challenge to popular memory probably went unnoticed by the early readers of Israel Potter who, even when being complimentary, saw little in the text beyond a pleasurable diversion. Yet Melville’s single book-length offering of historical fiction, dedicated “TO HIS HIGHNESS THE Bunker-Hill Monument” topples gilded memorials to the past and American nostalgia with his collage of the pirate-patriot-indigenous-foppish John Paul Jones. In lieu of monuments, Melville—against the grain of most of his contemporaries—leaves a democratic marker more fitting to the ideology and cultural fabric of the antebellum United States at mid-century; a marker that prophetically foreshadows a civil war that would tear the fabric of the nation to shreds.

Further reading:

For information on John Paul Jones, see Samuel Eliot Morison’s John Paul Jones: A Sailor‘s Biography (Boston, 1959) and the more recent Evan Thomas, John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, and Father of the American Navy (New York, 2003). For information on American identity and national mythology, see D.H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (New York, 1923); Richard Slotkin, Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860 (Middletown, Conn., 1973.) For information on homespun and its connection to the national imagination of the nineteenth century, see Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York, 2001).

For the primary sources quoted here, see Henry Brooke, Book of Pirates. (Philadelphia, 1841); Carrington Bowles, Paul Jones shooting a sailor who had attempted to strike his colours in an engagement (1779); Nathaniel Fanning, Narrative of the adventures of an American navy officer, who served during part of the American Revolution under the command of Com. John Paul Jones, Esq. (New-York, 1806); Florida pirate, or, An account of a cruise in the schooner Esparanza(New York, 1823); John Paul Jones, The interesting life, travels, voyages, and daring engagements, of that celebrated and justly renowned commander, Paul Jones. : Containing numerous anecdotes of undaunted courage, in the prosecution of his various enterprises. / Written by himself (Philadelphia, 1817); Life and Adventures of John Paul Jones (New York, 1846); Herman Melville, The Confidence Man: His Masquerade (1857) and Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1855); Charles Willson Peale, John Paul Jones, oil on canvas (1781); Israel R. Potter,Life and remarkable adventures of Israel R. Potter (Providence, 1824); Robert Sands, Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones (New York, 1830); “The Sea Captain, or Tit for Tat” (Boston, 1811).

This article originally appeared in issue 14.4 (Summer, 2014).

Anne Roth-Reinhardt is a lecturer at the University of Minnesota and a former Jay T. Last Fellow (2010) at the American Antiquarian Society.