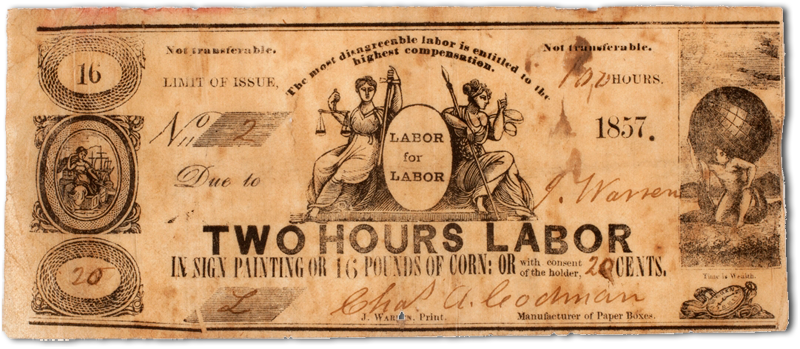

Josiah Warren’s Labor Notes

This labor note was created for Modern Times, a planned community founded in 1851 by Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrew, based on the idea of individual sovereignty. Like other utopian communities founded by Warren, the settlement used labor notes that enabled residents to trade their labor for the labor of their neighbors in a regulated system or through a time store, a shop run by Warren himself. The project sought to replace other forms of currency as part of Modern Times’ remaking of interpersonal economic relations. The community was located on ninety acres of land on Long Island about forty miles from New York City and its population had nearly peaked at about 150 people when this note was printed in 1857. Modern Times struggled through the Civil War years and eventually disbanded as a planned settlement, reincorporating as the town of Brentwood in 1864.

.

[Top text “Not Transferable”] It was important to Josiah Warren that labor notes not just function as replacement bank notes, but rather tie each individual’s labor to the exchange. He wanted to ensure that unintended parties could not get possession of the note to exploit someone else’s labor and what he called their “right of sovereignty.” Warren also wrote that making the notes useful only to the person trading their labor was one way of getting the parties involved to contemplate their own labor decisions and their value. This was why he printed notes unsigned and only filled them in at the time of exchange. Warren specifically wanted to make sure that only those individuals would receive notes who “understand and appreciate them.” Recognizing that there would be objections to the labor note project, Warren observed that during the initial stages of circulation in any of the time stores he founded that making the notes not transferable would prevent someone from obtaining a note to merely “make trouble and embarrass the operations.” There was a good legal reason for including such a disclaimer; it preempted the argument that Warren was circulating the labor notes as unregulated, illegal shinplasters—private, small denomination currency issues banned in several states. Another strategic decision in the design of the note might have been to place their endorsements on the face, rather than on the reverse, like most bank notes of the time. Labor notes promise of transparency meant that all relevant information; text, imagery, and signatures all appeared up front, while the back of the note was blank.

[Top Text “Limit of Issue 100 Hours”] Each individual that issued labor notes at Modern Times was meant to have total control over his or her labor and therefore total control over the amount of their labor that they were willing to assign to the labor notes. Most participants limited their issues to 100 hours, but the space was left blank to be filled in by hand, so that individuals could choose a limit. Such control over one’s own labor was an important part of the community’s version of individualistic utopia. Moncure Daniel Conway, who visited Modern Times in the 1850s, was told that it was founded “on the principle that each person shall mind his or her own business.” This seemed to be true for both spatial and commercial senses of the phrase “business”. Warren added that the community principle was to leave “every individual at all times at liberty to dispose of his or her person, time, and property in any manner in which his or her own feelings or judgment may dictate.” The idea of retaining personal authority over business and labor decisions also informed a contemporary English analysis of Warren’s magnum opus, Equitable Commerce that argued that one of the unique features of the labor note system is that “being based on individual credit it makes every man his own banker.” While it is hard to imagine Josiah Warren approving of being labeled a banker, given his distrust of banks and his belief that they prized making money from shuffling paper over earning money through productive labor, he would have appreciated the notion of each labor note recipient as master of their own economy.

[Text “1857”] Modern Times was founded in 1851 by Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrew as a planned community based on the idea of individual sovereignty. It was located on ninety acres of land on Long Island about 40 miles from New York City and had a population of about 150 people in 1857, near its peak. The community struggled through the Civil War years and eventually disbanded as a planned settlement, reincorporating as the town of Brentwood in 1864.

[Note made out to J. Warren for Two Hours Labor in Sign Painting or 16 Pounds of Corn: Or with the consent of the holder 20 cents] Modern Times was not self-sufficient and needed to obtain goods from the outside world to sell in the community’s time store (Warren’s shop based on labor for labor pricing), so residents had to calculate prices and pay for goods with a hybrid currency. While bank notes or specie paid for the price of an item, labor notes covered the payment of the surcharge to the store proprietor for their time making the sale. Away from the time store, Modern Times inhabitants wrote and traded labor for labor notes for any goods or services they wanted just as they would have any other paper money (with the exception of its being backed by labor or corn and not specie). However, the notes did not seem to have any life outside of the community and functioned only because residents that had already bought into the idea of living at Modern Times had confidence in the equitable commerce idea and the promise of each other’s future labor. Warren wanted to make sure that everyone could compare the price of their labor to everyone else’s labor and explained that corn worked extremely well as “the basis of a circulating medium” because “everybody who has land can raise it,” “it will keep, of uniform quality, from year to year,” and “it is too bulky to be stolen or secretly embezzeled (sic).” The inclusion, albeit in small print, of a cash option for the labor note spoke both to Warren’s desire for people to have options when accepting a labor note and to the realities of life at Modern Times. More options were also needed in the area, because even bank notes did not always trade easily in that part of Long Island. Especially during the years surrounding the banking problems associated with the financial Panic of 1857, bank notes did not circulate at face value in the area and only traded at a discount when they traded at all. Such flexibility was anticipated by William Pare in his 1856 review of Modern Times. He wrote that one of the advantages of the way that that labor notes presented their value was that it “represents an ascertained and definite amount of labour or property, which ordinary money does not.”

[Note signed by Charles A. Codman, Manufacturer of Paper Boxes for Two hours of sign painting] Charles A. Codman worked at “sign and decorative painting,” before moving to Modern Times with his wife Ada in 1857 and spending the next fifty four years as a resident. In the 1860 census Codman and cabinetmaker William U. Dame appear as paper boxmakers, but it is unclear how much work they ever accomplished in this area. No large-scale factory existed at Modern Times; the plans for one to make boxes may have been curtailed by the financial Panic of 1857.

[Note printed by J. Warren] In addition to other roles that Josiah Warren performed as one of the founders of Modern Times, he spent much of his time writing and printing commentary about the equity movement and his theories on labor for labor. From Long Island, he published Periodical Letter on the Principles and Progress of the Equity Movement between 1854-1858, as well as short pamphlets on “Positions Defined” and “Modern Education.” Warren also appears in the 1860 census as a lithographer.

[Top Center quote “The most disagreeable labor is entitled to the highest compensation”] This quote was not included on the earliest versions of Josiah Warren’s labor notes and reflected the addition of a Fourierist component to Warren’s figuring of transparent labor exchange value by ensuring a more favorable rate for harder or dirtier work. French philosopher Charles Fourier’s plans called for reorganizing society to eliminate poverty by creating independent, self-contained utopian “phalanxes” (ideally of exactly 1620 inhabitants each) where workers would labor according to their interests and be rewarded for their contributions to the community. Warren assimilated some Fourierist notions of compensation from the writings of Albert Brisbane, Fourierism most outspoken messenger in America after Fourier’s death in 1837. Brisbane’s utopian communal plan included a system for inversely rewarding dividends for labor based on three classes of industry: Necessity, Usefulness, and Attractiveness. Warren also later published a short pamphlet with the title The Principle of Equivalents. The Most Disagreeable Labor Entitled to the Highest Compensation in 1865. The pamphlet was even adapted for a foreign audience a few years later by A.C. Cudden, one of Warren’s English followers. Interestingly, the Fourierist North American Phalanx in New Jersey (1843-1855) and the Brook Farm community in Massachusetts during their phalanx phase (1844-1846), both printed small denomination paper money for internal use, so like at Warren’s utopian communities, the desire to break away from the industrializing American economy did not seem to come with a full reject of all of the conventions of trade and currency.

[Lower Right Corner Clock Image] Warren wrote in his private journal about clocks, using an extended metaphor to declare that “Society is the clock; individual liberty is the pendulum.” He explained this relationship by noting: “we must have the pendulum, and that pendulum must be in proportion to the other parts, or else although the machine would go, it would not be a clock. It would not measure time, and although a little variation in its length from the true proportion would be to surrender ‘only a portion’ of right, yet at the end of the year the machine for all purposes intended, would be worse than no clock.” Nineteenth century utopian thinkers confronted the delicate balance between the needs of the individual and the needs of the society and responded with a variety of answers. Warren’s program as enacted at Modern Times and his other communities shifted that balance as far as they could toward individual liberty and authority. While he acknowledged in his clock metaphor the clear link between society and the individual, he believed that it was the individual (as pendulum) that regulated the progress of society (the clock) and not the other way around. It also demonstrates that even for utopian communalists like Warren, the attempt to break free of the growing interconnected nature of industrial America’s market relations was not a simple project. It should be noted that the relationship of time to money was certainly not new to Warren; while few antebellum bank notes contained images of clocks, the Fugio cent, supposedly designed by Benjamin Franklin for the Continental Congress in 1787 featured an image of a sun over a sundial with the caption “Fugio,” Latin for I flee or hasten. Below the sundial were the words, “Mind Your Business.” Whether or not Warren was aware of the older coin, given Modern Times’ slogan of championing individual liberty and explicit call for everyone to mind their own business, the clock imagery seemed fitting.

[Left side top number 16 and left side bottom number 20] The numbers, mirroring the numerical values on a standard bank note of the era, showed exactly how much corn or potential cash the labor note was worth (other notes featured smaller amounts). For Warren it was necessary to have the numbers clearly printed on the note, so all of the parties involved in the transactions could be clear about the terms of the negotiation from the outset. He wrote that “all Labour is valued by the Time employed in it,”but was also insistent that assigning values for such labor was transparent, so that there were no questions of manipulation or fraud in the system. He noted that the “estimates of time cost, of articles having been obtained from those whose business it is to produce them, are always exposed to view, so that it may be readily ascertained, at what rate any article will be given and received.” Within this system of fair labor exchange, Warren believed, paper money was particularly useful because if a person deposited an item for sale, but did not want to make an equal withdrawal at the same time, they could receive “a Labour Note for the amount; with this note he will draw out articles, or obtain the labour of the keeper [of the store], whenever he may wish to do so.” This also helped facilitate trade with those who wanted to patronize the store at Modern Times, but did not have any labor to deposit for sale. Like every other transparent step in the process, Warren declared that “the keeper exhibits the bills of all his purchasers to public view so that the cost of every article may be known to all.”

[Left side Commerce Image] The vignette features a woman sitting on pile of crates and barrels with a transport ship in the distance and is meant to represent Commerce. The issue of rationalizing commerce and making it just preoccupied Josiah Warren, who wrote extensively on the subject in newspapers, pamphlets, and most notably the book seen as the main text on his political philosophy: Equitable Commerce: A New Development of Principles as Substitutes for Laws and Governments, for the Harmonious Adjustment and Regulation of the Pecuniary, Intellectual, and Moral Intercourse of Mankind Proposed as Elements of New Society. The first edition was published in 1846, with others following in 1849, 1852, 1869, and 1875. Warren’s notion of Equitable Commerce simply meant that labor should be properly respected and goods and services in the community should be traded at cost, eliminating any of the problems that arise from profit seeking, speculation, usury, or greed. Labor notes played a vital role in this plan because of their potential to replace money and make transactions more transparent and fair.

[Upper Right Atlas Image] While the vignette of Atlas holding the globe often symbolizes strength, constancy, and justice, another meaning of the image is related to production. Related to the burden that Atlas endures, he can be seen as a metaphor for the most productive segments of the population. It is also interesting here to think about the visual evolution of Warren’s notes from his initial attempts at labor for labor currency in Cincinnati in 1827 to this example from Modern Times thirty years later. The very first notes seem to be all text, while examples from the 1840s added a vignette of a blindfolded female statue holding scales and labeled “Justice.” The inclusion of the Atlas vignette and the one of Commerce on left side of the 1857 Modern Times note shows both a growing visual sophistication and more acceptance of the contemporary bank note style which usually featured vignettes and numbers on either side with text and a central vignette in the middle.

Further Reading:

The best modern treatment of Modern Times is Roger Wunderlich’s Low Living and High Thinking at Modern Times, New York (Syracuse, 1992); on Warren himself, see William Bailie’s Josiah Warren, the First American Anarchist (Boston, 1906). Albert Brisbane’s Association: or, A Concise Exposition of the Practical Part of Fourier’s Social Science (New York, 1843) provides a window to nineteenth-century communitarian thought. Warren laid out his own ideas in Equitable Commerce: A New Development of Principles as Substitutes for Laws and Governments, for the Harmonious Adjustment and Regulation of the Pecuniary, Intellectual, and Moral Intercourse of Mankind Proposed as Elements of New Society (New York, 1852) and True Civilization an Immediate Necessity, and the Last Ground of Hope for Mankind (Boston, 1863).

nb: In its original incarnation, this article featured an image of the note with roll-over textual explanations supported by qtip2 and jquery.maphilight.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.1 (October, 2012).

Joshua R. Greenberg is associate professor of history at Bridgewater State University. He is the author of Advocating the Man: Masculinity, Organized Labor, and the Household in New York, 1800-1840 (2009). His current work examines how early nineteenth-century Americans understood and used paper money.