Just Add Sparkling Grape Juice: Toasting and the Historical Imagination in the Early Republic Classroom

“Everybody get ready—lift your glasses and sing

Everybody get ready to lift your glasses and sing

Well, I’m standin’ on the table, I’m proposing a toast to the King.”

—Bob Dylan, “Summer Days”

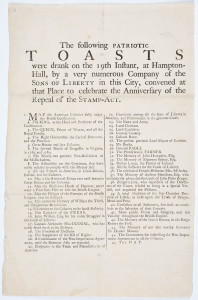

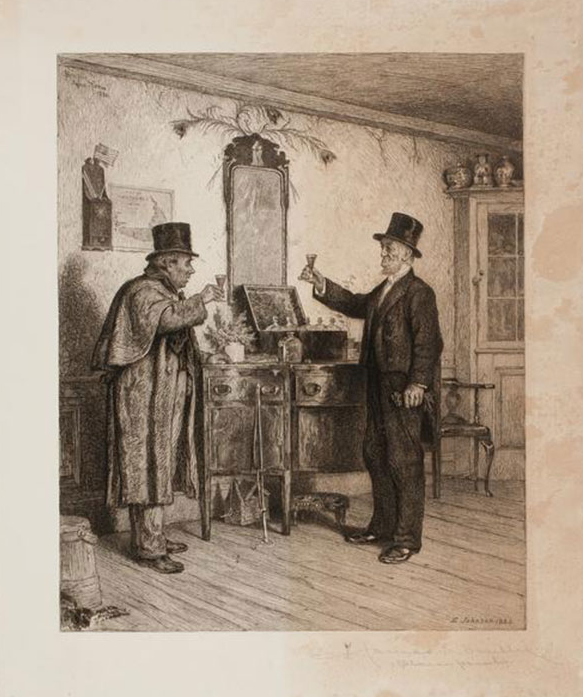

Today most people’s experience with toasting is limited to weddings. Toasts have long ceased to be a significant part of our political world, but in early America the practice of politics depended heavily on sociable drinking and toasting. At festive celebrations, men and women lifted their glasses to toast all sorts of subjects, from kings and presidents to military victories, legislation, principles, and historic events. Toasts variously praised, mocked, protested, or condemned their subjects. Their performance helped to create a convivial world of free-flowing conversation and song, food, and drink. Through toasting, individuals broadcast their political affiliations to the public. They also cemented social and political relationships, forging a sense of group belonging. By the end of the eighteenth century, toasts often appeared in newspapers, the expanding social media of the time. In this way, toasts not only reflected but potentially influenced public opinion.

To gain insight into the historical experience of toasting, students in my early republic class write and perform a series of toasts from the vantage point of the Federalists and Republicans of the 1790s. For three years, I have experimented with this activity in the classroom, and the toasting exercise has proven popular with my students. Preparing the toasts pushes them to develop their historical imaginations. Students step back into the past. As they write the toasts, they attempt to think in the language of 1790s politics. When they perform the toasts, they experience toasting as a social performance, an approximation of the historical experience of toasting in the early republic.

Historians trace the origins of toasting to the ancient world. Think of Plato’s Symposium, with participants at that famous banquet performing toasts on the subject of love. However, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, toasting achieved an unprecedented importance in European society. In eighteenth-century Britain, the practice complemented the rise of urban sociability. People ate and drank together in taverns and coffeehouses. They met in various societies with irresistibly fun names like the Kit-Cat Club, the Green Ribbon Club, the Red-Herring Club, the Easy Club of Edinburgh, the Beefsteak Club, and the Society of the Dilettanti. Clubbing was all the rage. In British North America, colonists emulated the sociability of the mother country. They established associations like the Junto in Philadelphia, the Tuesday Club of Annapolis, and the Old Colony Club of Plymouth. At these gatherings, participants shared laughter, made connections, devised self-improvement schemes, and advanced their reputations. These social occasions provided numerous opportunities to feast and toast.

During the American Revolution, toasting became highly combative. Patriots and Loyalists each tried to convince the public that their toasts represented the popular will. Americans carried forward this contentious style of politics into their new republic. Historians of the so-called “new, new political history” such as Susan Branson, Simon Newman, Jeffrey Pasley, and David Waldstreicher have reconstructed that vibrant political culture, demonstrating how ordinary men and women participated in politics by reading newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets, by organizing meetings, parades, and protests, and by attending festive dinners and other celebrations.

Toasting played a crucial role in shaping that increasingly partisan and democratic culture. Politics, Newman has emphasized, were not confined to voting on election day—and toasting rites belonged to a political world beyond the legislature in which non-elite individuals participated. Such practices enabled those who did not possess the franchise—men without property, women from all ranks, African Americans, and others—to stake their claim to the republic. Branson has demonstrated that during the partisan battles of the 1790s, women offered toasts on political subjects, even in mixed company gatherings, while the toasts offered by men sometimes appealed to women for their approval. Seth Cotlar has illustrated how artisans, mechanics, and other working men used toasting rituals to express their devotion to the French Revolution, particularly to the principles of liberty and egalitarianism associated with transatlantic radicalism. Waldstreicher has stressed that republican celebrations in opposition to the Washington administration, including the printed toasts that derived from those gatherings, contributed to the formation of a national opposition party, while Pasley has suggested that the toasts printed in newspapers actually represented an early version of a party platform.

The writing and performance of toasts was a social experience. Sometimes toasts were impromptu, but more often they were planned for maximum publicity. Before a gathering, a committee of arrangements would be charged with composing a series of toasts. Written individually or collectively, the toasts would all be reviewed and often revised by the committee before their performance. Since celebrants would never toast a sentiment with which they disagreed, such advance planning was necessary to ensure a display of unity. At these celebrations, consensus meant everything, historian Peter Thompson has argued. When performed, toasts would be followed by cheers, applause, sometimes music, and often in the case of militia companies, a ceremonial burst of artillery.

After the celebration, local newspaper editors received copies of the toasts to publish in their papers. As these newspapers circulated beyond their point of original publication, editors in other locations reprinted the toasts. Whereas few toasts from the colonial era circulated beyond the places where they had originated, toasts began being transmitted across the extended republic. When complaining to his wife about the toasts drunk at a Republican “frolic” in Philadelphia, Vice President John Adams asked Abigail: “Have you read them [?]” By the 1790s, Adams naturally anticipated that Philadelphia toasts might be reprinted in Boston. The circulation of printed toasts, along with other materials, pushed many Americans to start thinking nationally, as citizens in one location became increasingly aware of what other people across the nation were doing.

When I began teaching, I conceived of a toasting exercise as a method of conveying to students the participatory and performative nature of early republic politics. This idea was prompted by my own experience of writing and performing a series of toasts on regicide at a Summer Institute hosted by the Jack Miller Center for Teaching America’s Founding Principles and History. After performing these toasts, I gained a new understanding of the political culture that I had been reading about in books for so long. I wondered if a toasting activity could have the same intellectual impact on my students.

In the weeks preceding the assignment, students become familiar with the larger narrative of 1790s politics through lectures and readings. They learn about how Americans over the course of that decade grew divided between the Federalist supporters of the Washington administration and its Republican opponents. In class, we cover specific episodes to illustrate this polarization, from the battle over Alexander Hamilton’s financial policies to the contrasting attitudes toward the French Revolution, the controversy over Jay’s Treaty, the Alien and Sedition Acts, and the election crisis of 1800.

Students read and discuss several journal articles on popular political culture to complement this larger narrative. In past years, my syllabus has included articles by Waldstreicher on the legacy of revolutionary-era popular protests and festivities, Newman on celebrations of Washington’s leadership, Albrecht Koschnick on the Democratic-Republican Societies, and Pasley on the newspaper wars of the 1790s. These articles introduce students to the concepts of the public sphere and print culture, which enhance their understanding of the social and cultural contexts in which toasting rituals took place.

Students also analyze primary sources such as correspondence, addresses, and newspaper editorials from the period. In reading these sources, students learn about the arguments that appeared in print to justify various political positions. They further gain insight into the distinct language in which people discussed politics during the 1790s. On one occasion, a student observed that a newspaper correspondent used the word “jealous” in a way that differed from how people use the term today. While the term is largely used now as a synonym for “envious,” in the eighteenth century people used it to mean vigilant, as in the citizens jealously guarded their liberties. This observation led to a productive conversation in class about political vocabulary and how the meanings of words change over time.

Often when students first approach the partisan conflicts of the 1790s, they assume that those struggles paralleled today’s two-party political system. By reading the sources and then writing toasts, students reach a deeper, more nuanced level of historical understanding.

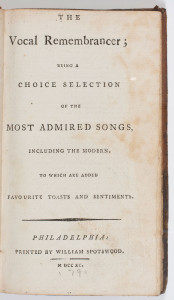

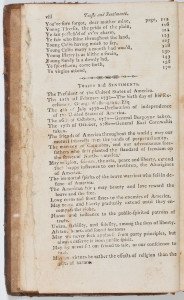

Finally, students read models of toasts culled from late eighteenth-century American newspapers. Toasts then fell into two categories. First, people drank healths to individuals like George Washington and to collective bodies like the Congress to demonstrate their admiration. Second, citizens drank sentiments to a wide variety of subjects. For example, at a joint celebration of the Democratic Society of Pennsylvania and the German-Republican Society of Philadelphia, participants drank to “the extinction of Monarchy,” adding: “May the next generation know kings only by the page of history, and wonder that such monsters were ever permitted to exist.” These examples give students a sense of the conventions of toasting that must shape their own historical toasts.

This combination of political narrative and readings in the secondary and primary sources prepares the students to work on their own toasts. For the exercise, the class divides into Federalists and Republicans. Working together, each team is charged with writing twenty toasts that reflect its politics. I advise students to begin by brainstorming the key issues of the 1790s and then figuring out their position on those subjects. Each team devises a list of topics such as the Bank of the United States or Jay’s Treaty, making sure that they adequately cover the decade’s political conflicts. The students proceed to experiment with writing their toasts, modeling them on the ones that they have read. They work together as I move around the classroom eavesdropping, advising, and reviewing their draft toasts. While I do not require students to meet outside of class to work on this assignment, the students invariably do this on their own initiative, either in person or virtually.

Typically, individual students take responsibility for writing three or four toasts. Even when they do this on their own, they interact with their peers and with me to revise their toasts. This activity encourages the writing process—brainstorming, drafting, and revising multiple times, which replicates the historical experience of writing toasts by committee. Students engage in this process in an intensive way that does not always happen when they write traditional essays. Maybe this particular assignment appeals to students who are immersed in the world of contemporary social media, like Twitter and Facebook. Perhaps also the knowledge that the students are going to perform these toasts in front of the class pushes them to perfect them. One student, for example, observed that “the pressure of sharing [the toasts] prompted me to do research beyond class notes.”

The major challenge students face in writing the toasts is putting their thoughts in apt historical language. One student quipped that “it was interesting and fun to use the lingo of the time,” but admitted that his group struggled to find the right words. After immersing themselves in the primary sources, students learn how keywords such as aristocrat and mob functioned as political insults during the 1790s. In one mock Republican sentiment, a student toasted: “To Mr. Hamilton’s Financial Plan: May the people come to see the true nature of the national debt as shackling the states to a federal aristocracy.” Another student, representing the Federalists, toasted the Democratic-Republican Societies “For showing us that the mob can be as tyrannical as the king.” Both toasts successfully employed the political vocabulary of the late eighteenth century, demonstrating that these students were thinking and writing in historical rather than contemporary terms. Often when students first approach the partisan conflicts of the 1790s, they assume that those struggles paralleled today’s two-party political system. By reading the sources and then writing toasts, students reach a deeper, more nuanced level of historical understanding. Students realize that in the early republic, Americans’ political vocabulary and assumptions about politics differed dramatically from their own, and that realization opens up a rich field for exploration.

I simulate the experience of historical toasting—and enhance the fun—by bringing plastic cups and a few bottles of sparkling grape juice, red and white, to class. A student who admitted to me that she was nervous before performing her toasts gained confidence when her team members responded to her toasts with several “Huzzas.” Through that collective cheering, students experience first-hand the social energies unleashed through toasting rituals. Ideally, if students connect their own emotions to those of the early republic’s citizens, they can make some valuable inferences about how the latter must have felt when toasting. Some students thrive on this social aspect of the assignment. The toasting exercise “helped me get to know my classmates,” commented one student, and theatre students particularly love the opportunity to connect history with performance.

Ultimately, this toasting exercise allows me and my students to bring the politics of the 1790s to life in our history classroom. Students are typically familiar with the traditional narrative of early American history, particularly the heroic representation of the founding fathers. They are less familiar with the political and cultural environment in which men like Washington, Jefferson, and Adams lived, a world that they shared with other lesser-known Americans who have not made it into the history books. In taking on the political identities of Federalists and Republicans, students imaginatively enter into that historical world. Ideally, in writing toasts, they gain insight into how people in the 1790s thought, and, in performing their toasts, they experience the social power of the early republic’s festive politics.

Further Reading

John Adams’s comments on the toasts drunk at the republican “frolic” in Philadelphia appear in Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, February 8, 1794. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive, Massachusetts Historical Society. The “extinction to monarchy” toast derived from The General Advertiser, May 3, 1793.

A good narrative of 1790s political developments can be found in James Roger Sharp, American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis (New Haven, 1995). For an overview of the “new, new political history,” see Jeffrey L. Pasley et al., Beyond the Founders: New Approaches to the Political History of the Early American Republic (Chapel Hill, 2004). On the British context of sociability, see Peter Clark, British Clubs and Societies, 1580-1800: The Origins of an Associational World (Oxford, 2000).

The last study that focused exclusively on toasting rituals appeared over sixty years ago: Richard J. Hooker, “The American Revolution Seen Through a Wine Glass,” The William and Mary Quarterly 11:1 (January 1954): 52-77. For a discussion of toasting within the larger context of alcohol consumption in early America, see Peter Thompson, “‘The Friendly Glass’: Drink and Gentility in Colonial Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 113:4 (October 1989): 549-573. Discussions of toasting also appear in the following works: Simon P. Newman, Parades and the Politics of the Street: Festive Culture in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia, 1999); Susan Branson, These Fiery Frenchified Dames: Women and Political Culture in Early National Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 2001); Seth Cotlar, Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of Transatlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic (Charlottesville, 2011); David Waldstreicher, In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776-1820 (Chapel Hill, 1997); Jeffrey L. Pasley, “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (Charlottesville, 2002).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.2 (Winter, 2016).

Michelle Orihel is an assistant professor in the Department of History, Sociology, and Anthropology at Southern Utah University. Her research focuses on politics and the print media in early American and Atlantic history. She is writing a book about the Democratic-Republican Societies and opposition politics in the trans-Appalachian West during the 1790s. She has published articles in The Historian and The New England Quarterly.