Ken Kesey Meets Lewis and Clark

The salmon fisheries of Celilo Falls

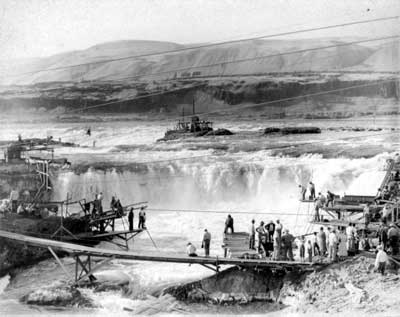

The area surrounding Celilo (pronounced “sea-lie-low”) Falls on the Columbia River is arguably the longest continually occupied place in North America. This is owing to one simple fact: Celilo Falls was once the greatest fishing site on planet Earth. The annual fish runs of the Columbia River, estimated at fifteen to twenty million salmon, had supported an essential human industry long pre-dating the arrival of Columbus in the Western Hemisphere.

All of this is now gone. One Sunday afternoon in March 1957 Celilo Falls and the ancient traditions of its fishing culture were drowned—smothered under the backwaters of The Dalles Dam.

Celilo Falls, its destruction, and the aftermath are among the most important and under-appreciated subtexts of Ken Kesey’s classic 1962 novel One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. Kesey was a native Oregonian. He planned and wrote the novel that defined the ’60s as this historic drama at Celilo Falls played out.

The narrator of Kesey’s novel is Chief Bromden. The mute giant, “Chief Broom” as he’s sometimes called, serves as a haunting embodiment of the shell-shocked Native peoples of the Columbia Plateau who had just lost the center of their ancient salmon-based culture. Celilo Falls had just been ripped from their heart; they were somewhat like Catholics who had just seen the Vatican bulldozed off the face of the earth. This important theme is completely missing in the film version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, starring Jack Nicholson. That is perhaps why so few Americans appreciate the historical significance of Chief Bromden.

I first got interested in this lost world of Celilo Falls in 1976 when my wife and I bought a cattle ranch on the breaks of the Klickitat River, in south-central Washington State. Our ranch sits where the timber meets the desert in the Pacific Northwest, a peninsula of land surrounded on three sides by one-thousand-foot-deep canyons, sixteen miles upstream from the Columbia River.

On my first trip to the Klickitat County Courthouse, I was waiting to purchase license tabs for my pickup truck when I noticed a huge black-and-white framed photo of Indians standing before a huge waterfall pulling mounds of salmon from the frothing river. They used large hoop nets mounted on handles fifteen to twenty feet long. “Where’s that?” I asked, pointing to the picture. “That was Celilo Falls…” the lady behind the counter answered in a voice of infinite sadness. This was for me the beginning of a thirty-year fascination with an enigma, Celilo Falls.

Celilo Falls was the economic and spiritual center of the Indian world in the Pacific Northwest. At Celilo, the churning waters of the Columbia slowed, confused, and blinded the migrating salmon so that the River People might easily catch them. The hot, parching summer winds at Celilo were perfect for drying and preserving a portion of the river’s bounty for the coming winter. This dried salmon, known as ch-lai, was pounded into a fine powder and tightly packed into baskets. It served as a kind of currency in a vast region of the West, stretching from Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming to northern California and Vancouver Island. In its final years, after many decades of declining fish runs, Celilo still produced two and a half million pounds of salmon annually. The salmon runs drew Native Americans from all across the West to help with the fishing at the falls.

Before it was eclipsed by the Hudson Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver in 1824, Celilo Falls was the hub of trade for the entire Pacific Northwest region. Natives came there to trade for many things other than salmon, including seashells, buffalo robes, obsidian, and slaves. They also gambled incessantly there, throwing the bones in the wildly popular “stick game” that had been played at the falls for thousands of years.

The Columbia carries more water to the Pacific than all the other rivers in Washington, Oregon, and California combined. Its maximum recorded flow was 1.25 million cubic feet per second. This occurred during the devastating flood of 1894. But that was a mere trickle compared to any of the Ice Age Bretz Floods that came roaring down the Columbia Gorge at ninety miles per hour and were over one thousand feet deep. Fifteen to twenty-five thousand years ago, a series of massive ice dams impounded much of the river’s enormous run-off east of the Rocky Mountains, turning most of eastern Montana into a lake. The geologic evidence shows that those ice dams broke repeatedly, releasing vast walls of water into the open flatlands of eastern Washington. From the saturated plains, the floodwaters traveled down to the Columbia Gorge, which they filled with a vast west-rushing torrent. From the Columbia’s headwaters to the Pacific, the floods erased all living things in their path. The archeological evidence found in the vicinity of Celilo during the “hurry-up” excavation that preceded the damming of the river, showed that human occupation at Celilo Falls went back in an unbroken string to that very last Ice Age flood, nearly eleven thousand years ago.

Economics were the central reason for those ten-thousand-plus years of occupation. The falls was one of the most productive food-gathering sites on the planet. Every year, as many as twenty million salmon (some researchers say even more) were drawn inexorably up the Columbia River to spawn and die in the gravel bars of their birth. On October 17, 1805, Meriwether Lewis’s co-commander William Clark observed that “the number of dead Salmon on the Shores & floating in the river is incrediable to Say…The Waters of this river is Clear, and a Salmon may be Seen at the deabth of 15 or 20 feet.”

The peoples of the Columbia steadfastly believed that these returning fish were gifts from the Creator, gifts of the earth, gifts that should be treated with both reverence and respect. For, in coming back to spawn, those fish had also come home to feed the River People; the salmon returned each year to Chi wana (the big river) so that the People might live.

The biggest of the Columbia River salmon, the “June hog”, weighed in at over fifty pounds. It had evolved to make a nearly one-thousand-mile, upriver journey from the ocean to the mountain streams of the Canadian Rockies. The June hogs disappeared from the face of the earth after the Grand Coulee Dam was constructed in the late 1930s. The dam lacked a fish ladder that would have allowed them to continue their millennia-old migration upriver. Today, along with the fourteen large hydroelectric dams on the main stem of the Columbia, there are 250 other dams at various sites throughout the drainage system. Half of the salmon’s historic range has been permanently blocked by dams.

The drowning of Celilo Falls in 1957 was simply the most recent and decisive conflict the Columbia River Indians have had with the whites. Their contact with European-based societies began about fifteen years prior to Captain Robert Gray’s 1792 discovery of the Columbia. Around 1775, smallpox from Russian sealers and fur traders had worked its way from Vancouver Island down the Pacific coast—long before the first physical contact—decimating native populations on the coast and up the river. This Old World plague came a full thirty years before the appearance of Lewis and Clark, whose arrival the River People had long prophesied.

In late October of 1805, when Lewis and Clark stopped to portage around Celilo Falls to the Long Narrows just below them, they found the salmon fishery recently finished for the year and emptied of most of its native residents. Left behind were countless vermin, living in the waste left from the manufacture of pounded dried salmon. According to Captain William Clark, by the time the Corps of Discovery landed below the falls, the party was “covered with flees which were So thick amoungst the Straw and fish Skins at the upper part of the portage at which place the natives had Camped not long Since; that every man of the party was obliged to Strip naked dureing the time of takeing over the canoes, that they might have the opportunity of brushing the flees of their legs and bodies.” In just one stack, Lewis and Clark counted 107 finely woven baskets containing thousands of pounds of dried, powdered fish. The cache had been left unattended while most of the people of the falls were off on their annual autumn trip to the huckleberry fields in the nearby mountains.

The journals of Lewis and Clark describe in close detail the Native fishing at Celilo Falls:

“Oct 22 1805…the waters [of the falls] is divided into several narrow chanels which pass through a hard black rock forming Islands of rocks at this Stage of the water, on those Islands of rocks as well as at and about their Lodges I observe great numbers of Stacks of pounded Salmon (butifully) neetly preserved in the following manner, ie after Suffiently Dried it is pounded between two Stones fine, and put into a speces of basket neatly made of grass and rushes of better than two feet long and one foot in Diamiter, which basket is lined with the Skins of Salmon Stretched and dried for this purpose, in this it is pressed down as hard as is possible, when full they Secure the open part with fish Skins across which they fasten tho’ the loops of the basket that part very Securely, and then on a Dry Situation they Set those baskets the Corded part up, their common Custom is to Set 7 as close as they can Stand and 5 on top of them, and secure them with mats which is raped around them and made fast with cords and Covered also with mats, those 12 baskets of from 90 to 100 w. each (basket) form a stack. thus preserved those fish may be kept Sound and Sweet Several years, as those people inform me, Great quantities as they inform us are Sold to the whites people who visit the mouth of this river as well as to the nativs below.”

The numerous baskets of ch-lai that Lewis and Clark saw represented only a portion of what was produced during the six-month fishing season, which began in April and ended in October. How many more tons of dried fish had already been traded away and carried into the hinterlands no one knows.

On their return journey the following spring, Lewis and Clark again passed by Celilo Falls. The fishing season had barely begun. Clark observed “all of those articles [the River People] precure from other nations who visit them for the purpose of exchanging those articles for their pounded fish of which they prepare great quantities. This is the Great Mart of all this Country.”

The modern Indian Nations on the Columbia Plateau—the Yakamas, the Warm Springs, the Nez Perce, and the Umatillas—are comprised of descendents of the far more numerous bands who once inhabited the Columbia Plateau. Epidemics, tens of thousands of settlers pouring over the Oregon Trail, and U.S. government policies did their best to shatter the Native peoples’ traditional ways of life. In the Treaty of 1854, signed at Port Elliot in Puget Sound, and then the Treaty of 1855, signed at Walla Walla, the Territorial governments set out to extinguish most Native land claims west of the Cascades and to cede to the Indians large reservations in the dry and almost worthless interior.

Many of the River Indians refused to leave for the reservations. The WyAm people of Celilo Falls were among the most steadfast of them. Chief Tommy Thompson, the last salmon chief at Celilo Village, always kept with him in a beaded deerskin pouch the treaty, which had been signed by his uncle Stocketly, granting the WyAms uncontested rights to fish at Celilo. Even though their treaty created a large new reservation, Warm Springs in central Oregon, the WyAms stayed on the river and continued to fish in the old way, even as the Army Corps of Engineers built The Dalles Dam.

In Ken Kesey’s version of the loss of Celilo Falls, Chief Bromden is the son of the chief who sold out the falls, a man who—in Kesey’s fictional rendering—becomes smaller and smaller as his white wife grows bigger and bigger.

About two-thirds of the way into the novel, Bromden’s friend, the defiant Randal McMurphy, asks Chief Bromden about his father and about the monumental forces working to make him little:

“…they beat him up in the alleys, and I told him that they wanted to make him see what he had in store for him only worse if he didn’t sign the papers giving everything to the government.”

“What did they want him to give to the government?”

“Everything. The tribe, the village, the falls…”

“Now I remember; you’re talking about the falls where the Indians used to spear salmon—long time ago. Yeah. But the way I remember it the tribe got paid some huge amount.”

“That’s what I said to him. He said, What can you pay for the way a man lives? He said, What can you pay for what a man is? They didn’t understand. Not even the tribe. They stood out in front of our door all holding those checks and they wanted him to tell them what to do now. They kept asking him to invest for them, or tell them where to go, or to buy a farm. But he was too little anymore. And he was too drunk, too. The Combine had whipped him. It beats everybody. It’ll beat you, too.”

Ken Kesey got many, many things right in this defining novel of the ’60s, but the Chief of the Falls selling out to the government definitely was not one of them. Yes, the government paid twenty-six million dollars for Celilo Falls. This was the amount its actuarial accountants calculated the fishing resources’ amortized value to be, figuring salmon at five cents per pound. And it was a huge fortune at the time. But the money did not go to Chief Tommy Thompson of the WyAm people, the keeper of Celilo Falls. It went instead to the reservation tribes who still came annually to the falls for the fishing but had left the life on the river years earlier.

Chief Thompson had refused to sell. For years before the dam was built, the Army Corps of Engineers would approach him, and every year he refused to take their money. He said, time and again, further negotiations were useless. But in the end, the government went around him. They used the power of eminent domain, condemning the falls in the courts. The government went ahead and built its dam anyway.

Even after The Dalles Dam was built, Chief Thompson still refused to take any money for Celilo. In addition, unlike the fictional character, Chief Tommy was not married to a white woman, and he didn’t drink himself into oblivion, either. The real Chief Tommy Thompson was a most exceptional human being, a cross between Jim Thorpe and the Pope. Tall, handsome, and athletic, a famed swimmer and boatman in his youth, he was married to as many as seven women at one time but never to a white woman; it would have been unthinkable. Chief Tommy Thompson was a holy man. His ancient religion was that of the Waashat, the drums.

Chief Tommy was 102 years old when the falls were drowned. He had begun serving as salmon chief at Celilo Village in 1875, when he was but twenty, after the death of the previous chief, his uncle Stocketly, who had been killed by friendly fire while serving as a scout for the U.S. Army. Tommy was salmon chief of Celilo Falls for the next eighty-five years, making him, without much question, the longest-serving public official in American history. Chief Tommy Thompson was also the most revered man on the river, the last true chief.

The death of Celilo Falls in 1957 foreshadowed the death of Chief Thompson two years later, at age 104. The River People believe he died of a broken heart.

Slipping now from memory, as the people who fished at Celilo Falls pass from this life, the history of the falls is in danger of disappearing. Celilo Falls and the deep well of culture there is so far below the radar screen of the dominant white society that a search of two popular encyclopedias—The On-line Columbia Encyclopedia and the last print edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica—reveals no entry under the heading of “Celilo Falls”. A trip to Google, thankfully, is far more productive.

With our modern engineering skills in the 1950s, we certainly could have done something very different. We could have improved the ship canal that had been built around the falls in the early 1900s, and we could have saved Celilo Falls and the rich life that went with it. If only we had put our minds to it.

This article originally appeared in issue 6.2 (January, 2006).

George Rohrbacher is a cattle rancher and an amateur historian. He lives near Centerville, Washington, three miles from his next-door neighbor. George is the inventor of The Farming Game, an award-winning educational board game, and is author of the memoir/love story, Zen Ranching. A former commissioner of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, he also served in the Washington State Senate. This article is adapted from George’s first novel, Celilo Falls … the story of a murder, which will be published in late spring 2006.