Kidnapped!: Tracking down a ripping good Irish-American tale

In London on St. Valentine’s Day in 1945, the aspiring young novelist Patrick O’Brian, today regarded as one of the great twentieth-century writers of historical fiction, received as a gift an early volume of the Gentleman’s Magazine. Published in 1744, it briefly recounted the sensational ordeal of an orphaned child named James Annesley. The presumptive heir to five aristocratic titles and sprawling estates in Ireland, England, and Wales, Annesley was kidnapped from Dublin in 1728 at the age of twelve and shipped by his Uncle Richard to America. Only after twelve more years, as an indentured servant in the backwoods of northern Delaware, did he successfully escape, ultimately returning to Dublin to bring his blood rival, now the earl of Anglesea, to justice in one of the epic legal struggles of the eighteenth century. “Wicked uncle, kidnapped heir, bastards, sudden death. Very gratifying,” O’Brian later recorded in his diary.

No saga of personal hardship and aristocratic skullduggery so captivated the British public in the eighteenth century as Annesley’s turbulent life. Following his return from America, it quickly became the “common conversation” of coffeehouses and sitting-rooms on both sides of the Irish Sea. With slight exaggeration, a London writer later reflected, “Starting from the low and ignominious state of a slave, he…at once engrossed the attention of the three kingdoms, more, I believe, than any private man ever did.”

This extraordinary tale inspired as many as five nineteenth-century novels. Set either in Ireland or Scotland, each revolved around the dramatic kidnapping of a young heir for the purpose not of extorting ransom but of usurping the lad’s patrimony. Sir Walter Scott’s Guy Mannering (1815) was the first to adopt this formula, but far and away the most famous novel to draw from Annesley’s life was the classic boy’s adventure, Kidnapped (1886), by Robert Louis Stevenson, which recounted the abduction of young David Balfour by his greedy Uncle Ebenezer. Like Annesley, Balfour is consigned to servitude in the American colonies, though he manages to escape after his ship wrecks off the coast of western Scotland. In the end, after a series of adventures in the Highlands, he at last succeeds in obtaining his inheritance.

Although Stevenson never evidently acknowledged his indebtedness, he was a voracious reader, especially of history, literature, and the law, and, in fact, was intimately familiar with Thomas Bayly Howell’s Complete Collection of State Trials…(London 1809-28) that included the Dublin trial of 1743 in which Annesley attempted to reclaim his birthright. Stevenson was also well-acquainted with Scott’s Guy Mannering, of which he owned a personal copy; and he also would have been familiar with Charles Reade’s popular novel, The Wandering Heir (1873), based largely on Annesley’s life.

At the time of Kidnapped’s publication, a critic wrote in the Athenaeum, London’s prominent literary magazine, “Of both ‘Guy Mannering’ and ‘Kidnapped’ the main action was suggested by the Annesley case, that marvelous romance of real life which, in ‘The Wandering Heir’, not even Charles Reade could effectually vulgarize and spoil for future use. And no doubt it may be said that in Balfour’s struggle with old Ebenezer there is nothing so improbable as the real struggle of Annesley with his wicked uncle, and that Annesley’s adventures in the plantations…surpass in wonderfulness any of the chances, escapes, and disasters that befell Balfour. More recently, the legal scholar David Luban has written of Annesley’s life, “Surely this is melodrama and not history.” The truth is that it is both, as I discovered in the course of writing a book about James Annesley with the aid of trial transcripts, newspaper accounts, and nearly 400 legal depositions located in the National Library of Ireland in Dublin and the National Archives outside London.

Certainly no historian could wish for a more dramatic tale or a more remarkable set of characters, from the king of England, George II, to a brave Dublin butcher and a wily Scottish merchant, both of whom befriended James. If his supporting cast is more credible than the dramatis personae of a novel by Defoe or Fielding, the members are every bit as colorful. A personal favorite is an elderly widow named Anstace O’Connor, who in 1742 confronted the earl of Anglesea for having kidnapped his nephew. Years earlier she had peddled oysters at Dunmain, the countryseat in County Wexford, seventy miles southwest of Dublin, where James was born in 1715. “The people are moaning because a great many here say you transported him [overseas],” protested O’Connor. Startled, Anglesea snapped, “No, you fool…hold your tongue!” After regaining his composure, the earl offered £40 if she’d swear that Annesley was the illegitimate son of a servant maid, which O’Connor adamantly refused, adding that she would not “take such an oath for all the world.”

But, of course, center stage is occupied by members of the house of Annesley, an English family who during the course of the1600s achieved wealth and fame in Ireland on a grand scale. Apart from personal tenacity and ambition, their rise owed much to Ireland’s dramatically transformed social order. Following a new wave of Elizabethan conquest in the late sixteenth century, Protestant adventurers like Capt. Robert Annesley, the younger son of a gentry family in Buckinghamshire, laid claim to confiscated estates, displacing the native Irish with English and Scottish tenants in the years preceding England’s colonization of North America. Annesley’s grant in 1589 of 2,600 acres in County Limerick was considerably smaller than Sir Walter Raleigh’s, but for an ambitious squire, it was a promising start.

The Annesleys were charter members of an Anglo-Irish upper class that historians have labeled the Protestant Ascendancy. Subsequent members of the family included Robert’s son Francis, a favorite of James I, who became vice treasurer of Ireland in 1625, and a grandson, Arthur Annesley, whom Charles II in 1682 made the earl of Anglesea, one of two English peerages that he received to accompany a pair of Irish titles. Appointed lord privy seal in 1673, the earl was a figure of considerable learning and culture, adopting the motto, from Horace, of Virtutis Amore (With Love of Virtue) for the family’s coat of arms. An acquaintance of John Locke and patron of the poet Andrew Marvell, Anglesea boasted the largest private library in Britain, not to mention vast estates in Ireland and England by the time of his death in 1686.

By any measure—honor, wealth, power—the first generations of Annesleys laid a formidable foundation for the family’s future success. No aristocratic house at the end of the seventeenth century could have expected more from its forebears. Equally important, there was no apparent shortage of male heirs, at least, that is, until the fifth generation. High rates of infant mortality were common during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and noble houses like the Annesleys experienced their share of mourning and loss. This, in itself, did not threaten to disrupt the male line, which ordinarily would have descended to the eldest son of the fifth earl of Anglesea, a leading Tory politician who twice served as privy councilor, first to William and Mary and later to George I. But the inability of the earl and his wife to conceive children meant that the family’s honors and estates, rather than descending directly on the main stem, would instead fork sideways, upon his death, to a remote bough of the genealogical tree inhabited by a younger cousin, Arthur Lord Altham, an impoverished baron and the future father of James Annesley.

In 1708, at nineteen years of age, Altham had abandoned his wife, Mary, in London and absconded to Ireland, where he owned land in Wexford, including much of the town of New Ross. Politics was not his passion as it had been for earlier generations of the family. A short, homely man of slight build with gray eyes and black eyebrows, he delighted in low pleasures, best expressed perhaps upon offering a servant employment. “If you come to live with me,” promised the baron, “you shall never want a shilling in your pocket, a gun to fowl, a horse to ride, or a whore” (the offer was accepted).

In time, Altham reconciled with his wife, long enough, at least, to guarantee the birth of a male heir, James, in 1715. Less than three years later, the baron falsely charged Mary with consorting in their bedchamber at Dunmain with a young country squire. “It’s true she bore him [James], and that’s all the pleasure she shall have of him,” he later stormed, having sent her off in a coach, never again to return. After which, on taking a commoner named Sally Gregory for a mistress, the baron became deeply indebted to her among numerous other creditors. Not only was Altham shortly charged with corruption by the Irish House of Lords, but he turned James out at eight years of age to fend for himself in the streets of Dublin, which the youth successfully did for three years as a shoeblack and errand boy. When taken to task for abandoning his son, the baron blamed Miss Gregory: “That bitch,” he protested, “will not suffer me to do any thing for him.” Despite Altham’s sudden death in 1727 at age thirty-eight, no one felt sufficiently concerned to investigate the circumstances. No coroner’s jury convened, and no autopsy was performed on the corpse before it was interred on the night of his passing in Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral.

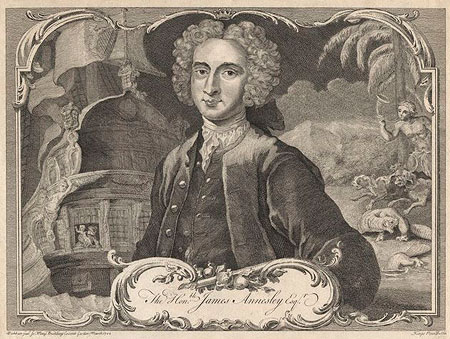

![It is not known whether Annesley posed for this portrait, which originally appeared in one of the published Court of Exchequer trial transcripts. Note the ship to the left, with an infant [Annesley was actually twelve at the time] held aloft in a stern window, and to the right an American scene replete with a palm tree, a half-naked youth with a horn, a pack of hounds, and a pair of beavers. James Annesley by George Bickham the Younger, after Kings line engraving (1744). Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London, England.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/49-300x226.jpg)

The protagonists of the saga, of course, are James, the orphaned son, and his Uncle Richard, Lord Altham’s estranged brother, who in addition to being a serial bigamist was if anything more rapacious, the consequence perhaps of being a younger son with neither rank nor financial security. As the brother of a lowly baron, he was not even permitted to use the coveted title of “Lord.” By one account, Richard was of middling height and had the “clumsy manner of a country farmer.” Unfortunately, no known portrait has survived, nor was he the sort to sit for one. Owing to both his appearance and character, a female acquaintance later volunteered, “I would not have had him if I was young, no, not [even] to be a countess.”

Just three weeks before Baron Altham’s death, Richard had paid James, or Jemmy as he was still called, a visit at the home of John Purcell, a warm-hearted butcher who, together with his wife, had taken the boy into their home just north of the River Liffey that bisected Dublin. Do you, Richard asked the butcher, have a boy in the house named James Annesley? Yes, replied Purcell, calling the lad, hesitantly, from the fireside, once and then a second time. Stricken with fright, his eyes beginning to moisten, Jemmy whispered to “Mammy,” Purcell’s wife, “That is my Uncle Dick.”

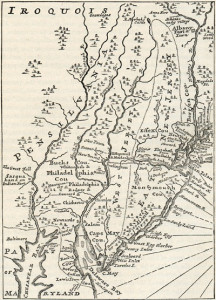

The boy’s fear was well founded. Following his mother’s banishment ten years earlier from Dunmain, Richard had cursed Altham for not turning out the boy as well. “Damn my blood,” he’d railed, “I would have let her have him, and she might carry him to the devil, for I would keep none of the breed of her.” Circumstantial evidence, in fact, strongly suggests that Richard had his brother poisoned, thereby leaving James as the final obstacle to Altham’s barony along with four more peerages that his nephew stood to inherit. On April 30, 1728, James was grabbed in Dublin’s Ormond Market, bundled into a coach, transported to George’s Quay alongside the Liffey, and carried aboard a vessel, brimming with servants, that was bound for Newcastle, Delaware. Unlike Balfour’s escape in Kidnapped, Annesley was less fortunate, ultimately being forced to toil for twelve years after being sold to a merchant-farmer in Newcastle County named Duncan Drummond.

That Annesley survived for such a length of time as an indentured servant in northern Delaware was a testament to his resilience. In contrast to immigrants who sought to make new lives in the colonies, he held fast to his identity. Not only did he proclaim his rightful origins in hopes of finding a sympathetic ear, but he was said to shun the company of other servants. During the boy’s early years, there had been flashes of pride in his lineage, even as a street waif in Dublin. At the same time, he had an outward ability to adapt to different settings and new hardships. Instability had long been a way of life for him; if anything, it may have eased his adjustment to the life of a servant, however punishing the ordeal or wrenching his separation from Ireland.

Upon James’s flight in 1740—successfully absconding on his third attempt to run away—first to Philadelphia, then to Jamaica, to London, and finally to Ireland, his Uncle Richard, now the sixth Earl of Anglesea, repeatedly tried to have him killed. In November 1743, the two commenced a titanic struggle at the Court of Exchequer in Dublin in what newspapers later declared the longest trial (nearly two weeks) ever heard by a British jury. A total of twenty-eight barristers participated. Never before had five peerages and such an immense estate been at the disposal of the legal system. By one account, the property was worth at least £50,000 a year.

No less momentous in the public mind at the time of the trial were allegations of aristocratic wrongdoing, which, for James’s following, had robbed a peer of the realm of his birthright and broken the chain of succession within the house of Annesley. Richard’s circle, by contrast, bewailed the prospect of elevating a false claimant to the family’s hereditary honors, not unlike Jacobite efforts to place a Stuart heir on the throne. Opponents commonly derided James as a “pretender,” the slur attached to successive generations of Jacobite claimants. Annesley’s contest, claimed Viscount Perceval in a letter to his father, was “perhaps of greater importance than any tryall ever known in this or any other kingdom.”

The jury found in Annesley’s favor, but his uncle’s appeal set the verdict aside for eight years, as yet new fronts opened in and out of court on both sides of the Irish Sea. As to whether the young claimant finally achieved justice, it is a tale full of unforeseen twists and turns that persisted well after the deaths of both James and his uncle in the early 1760s. “Revenge,” as the saying goes, “is a dish that is best served cold”—even, as events turned out, from the grave.

Although it might seem odd that historians have largely ignored the tribulations of James Annesley, reasons for scholarly indifference are not difficult to find. To begin with, the best-known source associated with Annesley’s abduction is a volume, first published in 1743, titled Memoirs of an Unfortunate Young Nobleman, Return’d from a Thirteen Years Slavery in America, ‘Where he had been sent by the Wicked Contrivances of his Cruel Uncle. Reprinted innumerable times, it is easily dismissed as sentimental fiction, written at a time when overblown stories of high adventure were a popular literary genre. Were the protagonist, modeled loosely after Annesley, of humble origins and a roguish bent, the style might be labeled picaresque, similar to that of Moll Flanders (1722) and Tom Jones (1749).

I first encountered Annesley’s purported memoirs nearly thirty years ago when researching a book, Bound for America (1987), about the banishment of British convicts to North America during the 1700s. My instinctive reaction was much the same, I suspect, as that of most others: to dismiss the volume out of hand as fiction, and bad fiction at that. In 1975, in fact, a reprint had been put out as part of Garland Publishing’s “Flowering of the Novel” series.

In retrospect, like other eighteenth-century narratives set in British North America such as The Infortunate, written by the former servant William Moraley (1743), it is now clear that the Memoirs blended fact with fiction. Although Annesley himself was not the writer (the book’s florid style alone discounts that possibility), only he could have been the author’s principal source of information. Once stripped of their romantic hyperbole, events in the Memoirs for the most part ring true, and references to names and places usually prove accurate.

That James Annesley’s story has gone untold cannot, however, be attributed solely to the false scent left by a Georgian narrative—especially if we consider, beginning in the 1960s, the publication in academic journals of several short articles devoted to different aspects of Annesley’s life by the late Lillian de la Torre, a prolific mystery writer. Those articles notwithstanding, the larger story of James Annesley has invariably failed to draw scholarly attention.

A second explanation lies, perhaps, in the problematic nature of the legal evidence, particularly a transcript of the climactic trial in Dublin between James and his uncle that was published with a long introduction in 1912. The principal dilemma in using this document and, for that matter, other legal sources, including depositions, was the contradictory nature of much of the testimony. Perjury, I quickly realized, whether in court or in a sworn affidavit, was a persistent problem in eighteenth-century Ireland. In the historical novel Castle Rackrent (1800), Maria Edgeworth contrasts the “Englishman who expects justice” at court with the “Irishman who hopes for partiality.” The extent of perjury during the trial in 1743 was unusually flagrant. Although disagreements between witnesses arose over dates, places, and personalities, invariably the underlying point of contention was the same: whether or not James Annesley was the legitimate son of Lord and Lady Altham and, in turn, the rightful heir to the honors and property of the house of Annesley.

How, then, best to determine the facts of the controversy? As much as possible, I tried to shed any presuppositions, despite a natural inclination to sympathize with Annesley’s plight (bastard or not, he was abducted by his uncle). Grasping heirs and bogus claimants are common enough in British history, if rarely on the scale alleged by Annesley’s enemies. And there was always the chance, I recognized, that James himself, however sincere his protestations, might not have known the true details of his birth.

In the end, my task turned out to be less tortuous than I first imagined. Despite its inconsistencies, the totality of the evidence veered strongly in Annesley’s favor. Independent sources, when available, almost always corroborated the claims of James and his followers. With few exceptions, their statements were more apt to be accurate. Testimony favoring Annesley during the course of his lawsuits typically seemed more credible than that of his opponents. If his witnesses were less artful, their responses were less contrived.

The earl, of course, alone commanded the resources and authority to suborn legal testimony, particularly in County Wexford where he resided. Not only was he the most prominent member of the county’s landed class, but his assets dwarfed those of his nephew. In stark contrast, when James returned to Ireland in 1742, he enjoyed neither personal connections nor political influence, much less the wherewithal to sway witnesses. It was, I concluded, the merits of his cause that drew such large numbers of supporters, many of whom still recalled the young lord, Jemmy Annesley.

Finally, I decided that no explanation other than a desire to deny James’s birthright could account for Richard’s relentless persecution, which his legal counsel never successfully disputed. Neither Anglesea nor his lawyers ever offered a consistent explanation for Jemmy’s disappearance in 1728. Initially, Richard reported his nephew’s death from smallpox. Afterward, to a circle of intimates, he related “in an easy manner” that the boy “was gone.” Still later, he stated to a friend that Jemmy had died in the West Indies.

These very real methodological problems help to explain scholarly inattention to the Annelsey story. But the full answer, I suspect, also lies in the predilections of academic historians. For social historians, the principal appeal of Annesley’s saga would seem restricted to the backdrop of eighteenth-century Ireland. What might this tale have to say about Irish society, especially the roles played by class, gender, religion, and ethnicity? Meanwhile, cultural historians might be drawn, if at all, to Annesley’s representation in literature and the press. The sensational events of his life would have less appeal in their own right.

More surprising perhaps is that popular historians have not been attracted to a story peopled by larger-than-life figures, complete with a plot overflowing with venality and violence. After all, the tale was sufficiently dramatic to capture the interests of Scott and Stevenson, among others. How could five novelists be wrong, not to mention the studios of Walt Disney, which employed the same formula by pitting an orphaned lion cub, Simba, against his wicked uncle, Scar, in the enormously successful movie, “The Lion King,” followed soon by an even more successful Broadway production?

Alas, for most popular historians, Annesley’s ordeal possesses two fatal flaws. Not only are the antagonists lacking in intrinsic importance, but James’s life, however extraordinary, left little lasting imprint on the historical landscape. Although his abduction by Uncle Richard represented a breathtaking act of treachery in a family drama that unfolded on two continents over seven decades—to the rapt fascination of the British public—the fate of the house of Annesley had no enduring impact upon the past, unlike the aftershocks of revolutions, battlefield heroics, and presidential elections. Nor does this story throw new light on the momentous events of the era, be they wars for empire, scientific discoveries, or the origins of the Industrial Revolution.

Following the return of young Annesley to Dublin in 1743, the Irish Parliament did pass legislation designed to impede the kidnapping of paupers, but the bill was overruled at the behest of officials in London. Kidnapping was destined to remain for many years, under the common law, a misdemeanor, whereas horse theft, a felony, was punishable by death.

Other than providing fodder for novelists, the only other tangible legacy lies in Annesley’s courtroom contests—two trials in particular established legal landmarks, one in the pioneering use of forensic evidence, whereas the other all but gutted the principle of attorney client privilege, a ruling that would dominate British courts for another half century.

Such, then, is the thin gruel that these events offer two different sets of historians—those, on the one hand, who fill the shelves of Barnes and Noble, and others of a more academic bent, prone periodically to deriding popular historians for chronicling the deeds of “dead white men on horseback,” including presumably the shenanigans of British aristocrats.

Fourteen years ago, the novelist Margaret Atwood described her goals in writing historical fiction: “Such stories are not about this or that slice of the past, or this or that political or social event, or this or that city or country or nationality, although of course all of these may enter into the picture, and often do. They are about human nature, which usually means, they are about pride, envy, avarice, lust, sloth, gluttony, and anger”—but also such qualities as love, forgiveness, and charity. Not long afterward, John Demos urged fellow scholars to set a similar task in their own studies, albeit by drawing directly upon the hard evidence of the past—in short, to compose compelling narratives, enriched by a wealth of detail, that reveal human nature in all of its complexity. The critical difference between this and fiction is that for a majority of historians, the past still enjoys the virtue of being more authentic.

In truth, the strategy favored by Atwood and Demos incorporates the strengths of both popular and academic historians. To be sure, many of today’s scholars, in their efforts to analyze patterns of human behavior, more often look at bodies of people, be they ethnic groups, voting blocs, consumers, or social classes. By contrast, Demos and Atwood, in their desire to fathom “the foundations” of “the human condition,” are more concerned with individuals, a tact that may or may not involve the writing of a biography. But this difference in approach, while important, verges on being a subtle, dare one say academic, distinction. The broader point is that Atwood and Demos share with most scholarly historians a desire to plumb the depths of humanity in whatever guise or form. If their methodology adopts, in part, the apparatus of popular authors by favoring well-told stories, replete with memorable events and individuals, their objective, still and all, is to foster a deeper level of understanding.

One of my aims in resurrecting the saga of James Annesley was to illuminate eighteenth-century Irish society, thanks largely to the vast trove of legal documents that members of the Annesley family left in their wake. The sheer density of the depositions, many containing richly detailed recollections of rural Ireland, is stunning. They speak not only of the minutiae of everyday existence—the clothing, furnishings, and customs of lords and peasants—but also of the cadences of Irish life.

But I set out primarily to write a narrative, not unlike, in purpose at least, Atwood’s novels—a story that would hopefully capture the imagination of readers, much as James Annesley’s ordeal had drawn the attention of a young Patrick O’Brian and, sixty years earlier, had inspired Robert Louis Stevenson. Although the Annesleys were scarcely the only noble house in the British Isles racked by internal discord in the eighteenth century, they fought the bulk of their battles at uncommonly close quarters. The ferocity of the family’s clashes over rank and wealth cut to its very core, pitting husband against wife, father against son, and brother against brother. James’s abduction by his Uncle Richard was only the most brazen act of treachery, neither the first nor, surely, the final breach of trust in this violent family drama. Ultimately, then, besides whatever light it sheds on eighteenth-century Ireland, the ordeal of James Anneslsey is a tale of betrayal and loss—but also, I like to think, of endurance, survival, and redemption.

Further reading

For more on the Annesley family saga, see A. Roger Ekirch’s Birthright: The True Story that Inspired “Kidnapped” (New York, 2010) and “Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Kidnapped’. . . The True Story,” The Scotsman (Edinburgh), (March 6, 2010). Originally delivered as the Bronfman Lecture in November 1996 in Ottawa, Margaret Atwood’s remarks on historical fiction (“In Search of Alias Grace: On Writing Canadian Historical Fiction”) were printed in the American Historical Review 103:5 (December 1998): 1503-1516 as was, in the same issue, John Demos’s essay, “In Search of Reasons for Historians to Read Novels” (1526-1529).

This article originally appeared in issue 11.1 (October, 2010).

A. Roger Ekirch is a professor of history at Virginia Tech.