“Like standing on the edge of the world and looking away into heaven”

Picturing Chinese labor and industrial velocity in the Gilded Age

In late 1869, just months after the transcontinental railroad linkage was completed at Promontory Point, Utah, a young illustrator for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was ordered by his publisher to make a trip across the nation on a railway sketching tour. As Joseph Becker, who would later serve as head of the periodical’s art department, remembered in a 1905 interview, the illustrated “Across the Continent” series that came out of his journey turned out to be a celebrated media event. For the first time, it was possible to traverse the entire country in one fluid, industrial sweep, and the “special artist” was there to experience and transmit this watershed event on behalf of his paper.

Using the railroad to move with due speed across the vast nation, Becker was able to send back to his editors illustrations of far-flung places. Among the subjects he was told to illustrate were the Chinese immigrants who labored on the railroad. Actually, as he revealed in his interview, this was the principal purpose of his trip:

Mr. Leslie commissioned me to go to California to portray the Chinese who had come over in large numbers to build the Union Pacific Railway. These people were then a novel addition to our population, and Mr. Leslie planned a “scoop” on our competitors. My destination was kept a secret. I reached California in due time, [and] spent many weeks among the celestials, making drawings.

In addition to scooping other periodicals with novel subject matter, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper wanted to be the first major periodical to use the transcontinental railroad to bring news to Americans on the East Coast. Indeed, nearly forty years after his sketching voyage, Becker still bragged that he had “scored ‘beats’” for having portrayed the Chinese. That is, using the new transcontinental railroad, he brought those illustrations to press before anyone else did.

In a Becker illustration bearing the caption “Across the Continent—In the Sierra Nevada, on the Line of the Pacific Railroad,” from the March 5, 1870, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, small figures pose on and beside the train tracks, which have wended their way through towering mountains in the background (fig. 1). In many ways, the image is typical of those the artist’s publisher likely expected him to create. By drawing the viewer’s eyes along the railroad tracks, it unites grand vistas with exoticism and technological prowess. As Thomas Knox, the journalist traveling with Becker, described the scene, it is one in which “mountains rise abruptly and in front on either hand, while immediately before us is the road and the river . . . and the huts of Chinese laborers.”

If Becker was the first pictorial journalist to make a cross-country exploration—one in which he kept a vigilant eye out for any Chinese immigrants—he was hardly the last. Throughout the 1870s, such expeditions constituted an entire genre of travel writing. Writers as popular as Robert Louis Stevenson and Charles Nordhoff and other periodicals as widely read as Harper’s Weekly also turned out first-person accounts of rail travel from coast to coast. Indeed, in 1877 Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was still sticking by the transcontinental article series. It was doing so, in fact, in the most high-profile fashion. In addition to Becker’s 1869 voyage, the popular newspaper revisited the transcontinental series in 1877 when publisher Frank Leslie himself undertook a tour, even repeating part of the original title: “Across the Continent—The Frank Leslie Transcontinental Excursion.” This series featured the work of staff artists Harry Ogden and Walter Yaeger. Among the many such accounts produced, these two series were especially prominent for the lengths of time they ran, the geographical territory they covered, the number of illustrations they produced, and the large readership they likely commanded. This last, because both were published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, which was, together with Harper’s Weekly, the leading illustrated weekly of the day.

The scenes created during both of these cross-country assignments revealed the vastness of the national landscape, the means by which industrial achievement allowed Americans to traverse the nation with great speed, and the ways representations of Chinese workers were essential to that formula. These illustrated transcontinental tours were self-conscious, stylized productions, heralding the railroad as the preeminent icon of modernity. To that end, illustrators repeatedly turned to the figure of the Chinese immigrant in portraying the railroad as an unprecedented invention that could race across national space. Relying on such a juxtaposition, Joseph Becker’s “The Snowsheds on the Central Pacific Railroad in the Sierra Nevada Mountains,” which appeared as an engraved double-page supplement to the February 5, 1870, edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, showed Chinese workers returning salutations from occupants on a passing train.

Becker’s placement of the railroad laborers gave readers the opportunity to linger over the “exotic” nature of the workers’ appearance—the fall of dark queues down shoulders and backs draped in loose-fitting shirts or the wide, round brims of straw hats. At the same time, the stationary positions of the workers served as a counterpoint to the forward momentum of the train. Moreover, as they salute the train, their bodies resting on lowered shovels, the train’s movement through the landscape is emphasized by several pictorial details. Trailing wisps of smoke from the engine, the successive progression of cars, and that long fragment of track extending from a distant background through the left foreground where a snowshed ensures the train’s continued passage—all of these elements demonstrate the consistent speed of the train as it passes its ardent yet inert observers.

Text accompanying the illustration describes passengers experiencing the railroad in the Sierras as it “hangs over deep valleys, that make the brain whirl when the eye is turned into their depths; and again it passes along high embankments, and shoots suddenly into tunnels that pierce solid rock, and save a high ascent to the skies.” These lines reveal an acute awareness of the rushing landscape. Here a sense of speed is conveyed with a vertigo-inspired intensity. In this illustrated article, the velocity of the train provides for a new kind of “panoramic” vision in which elements of the landscape—such as mountains, valleys, and rivers—acquire a new connection to one another. In this context, Chinese immigrants become one feature on—but not necessarily “of”—this novel, passing scene. Mesmerized and physically “sidelined” by the train, they linger somewhere between the landscape all around them and the speeding railroad cars before them.

What is happening here, in relation to the sidelined workers, is a kind of visual transference. One of the attributes of mechanical speed, as cultural historians have explained, is its ability to become a new space upon the plane of a constantly receding picturesque landscape. It was not simply the case that traveling at speed inspired new sensations. Additionally, and far more radically, mechanical velocity created a new realm of sensation—one that was experienced as wholly separate from and intrinsically different from its surroundings. Becker’s illustration reveals that this transformation of mechanical speed into a new form of space, one of the most basic experiences of industrial modernity, was also marked by considerations of the racialized, laboring immigrant presence that made such a shift possible—and particularly in relation to an ambivalent awareness of Chinese presence. In this image, then, Chinese workers are depicted less as the creators of that industrial space and more as its visualized parameters. Like sentinels of industrial change posted between the locomotive and the natural landscape, they witness and react to the mechanical velocity of the railroad, even as it leaves them behind.

If Chinese figures helped reinforce the notion of industrial speed as its own new kind of space, what sort of meaning was that space imbued with in relation to their watchful forms? How did the returned gaze of Chinese laborers function in relation to envisioned awareness of industrial speed? In anotherillustration, published in 1878, railroad laborers are again depicted pausing in their work (something they probably did far more within the pages of the periodical than in real life) in order to stare at a passing train (fig. 2).As the engine passes them on a tight curve, the workers are hemmed in on one side by its shiny mass. A rider near the conductor’s compartment regards them while various other figures atop the trailing cars mimic his pose. Meanwhile, on the other side of the seated workers, the approach of another figure, probably a foreman, is made ominous by the gun he carries and the dog he leads. Here again, the static and liminal pose of the observing Chinese laborers is pronounced. It is actually even more emphatic than it was in Becker’s earlier sketch because its composition is more constricted. The workers’ pose is enforced not only by the steeply angled mountain landscape but also by the imposing presence of both the train and the gun-toting figure.

And, again, the matrix of locomotive speed and natural grandeur is highlighted in juxtaposition to the stationary laborers. Establishing the contrast to the workers’ stillness, the text announces, “we have reached Cape Horn, the steep jutting promontory which frowns at the head of the Great American Canon [sic], and the train swings round it on a dizzily narrow grade, a wall of rock towering above, and the almost vertical side of the abyss sweeping down below.” “[I]t is like standing,” the reporter concluded, “on the edge of the world and looking away into heaven—a heaven where verily ‘God hath made all things new.’”

Constrained as they are by the power of the speeding locomotive and the authority of the approaching foreman, the workers are unable to share in this sublime moment. Yet, if there is a temptation to see them only as a “captive audience,” we must account for the waving figure among them as well as the sense that their interest was genuine. Indeed, in both of these illustrations, the seriousness with which the workers view the train is too obvious to be incidental. Further, these illustrations feature more than Chinese simply looking in wonder. They also depict railroad passengers aware that they are being observed by a stationary audience as they themselves traverse the land with industrial swiftness and ease. The sense of industrial movement is thus underscored by the gaze of Chinese laborers. The latter’s static and observant presence helps to characterize the pictorial representation as admirable, enviable, even marvelous.

Unsurprisingly, if a “sidelined” Chinese presence evokes remarkable industrial space, the effect of such positioning on the laboring figures themselves is hardly celebratory. Instead, the individual laborers and the nature of their work are obscured. In another two illustrations, for instance—”Wood Shoots in the Sierra Nevada” and “The Truckee, The Great River in the Sierra Nevada, Near the Pacific Railroad” (figs. 3 and 4)—the trackside figures are actually doing something more than admiring a passing train. In the first illustration, they stack railroad ties. In the second, they pass to and fro over the tracks while working. However, within the context of both the illustrated articles, even these obvious activities are obscured.

In “Wood Shoots in the Sierra Nevada,” laborers are positioned at the base of the wood shoots, which fall in descending lines from the top corners of the frame to meet with the railroad tracks. The men are enclosed on all sides by the narrow verticality of the natural environment, and also by the built structures of industrial progress. The only rationale for the presence of these figures is their work. Yet, details of its exact nature are sacrificed to the panoramic view of tracks sliding through the landscape. If, in relation to the train, workers are static, in relation to the natural environment they become minute and even crudely drawn.

“The Truckee,” the second image, also obscures laborers’ actions by again maintaining the contrast between these figures and their surroundings. Their role is not centered on the train tracks; rather, their importance is determined, like the “Great River” itself, by proximity to what is truly significant. Both are understood, as the caption declares, to be “near the Pacific Railroad” and not the other way around. That is, it is their presence that is defined in relation to the newly existing railroad. Or, as the article announces, “One of the surveyors of the Central Pacific Railway declared, after the route for the iron horse was finished, that the Truckee River was especially designed by nature for the accommodation of the company.” In this illustration, Chinese figures are actually rendered part of the landscape by the railroad—like rocks, trees, and rivers, it naturalizes them as a feature of the passing panoramic scenery. Perhaps even more than that, and this applies to figures in both engravings, these workers are also diminished by the unseen presence of the train. As the tracks extend out of the frame and toward the viewer, the illustrations maintain the sense that these figures are receding into the land and falling away from the train.

Ultimately, the Chinese are marked in invidious comparison to the velocity of passing trains. Their positioning both subjugates them to and holds them at a remove from the pivotal point of modern industrial activity. “Sidelined” by the railroad, connected to it while distanced from it, these workers appear as a visual contrast to the rushing mass of the train. In contrast, when white figures made an appearance in the Leslie’s article series, as they do in an 1877 station scene bearing the caption “The View of the Town of Sydney, the Nearest Railroad Station to the Black Hills,” they were aligned with the approach of civilization in a way that the Chinese were not (fig. 5).< The white figures in this engraving are thus posed against the outlines of a growing commercial town. The passing trains have little effect upon them. Other groups in other illustrations also escaped Chinese labor’s thrall to a fast-paced train. For example, European immigrants were generally characterized in ways similar to “generically” white Americans whose ethnicity, as is the case in the station scene, receives no obvious visual elaboration. And as for Native Americans, they were often portrayed fleeing the train—unless of course they were attacking it.

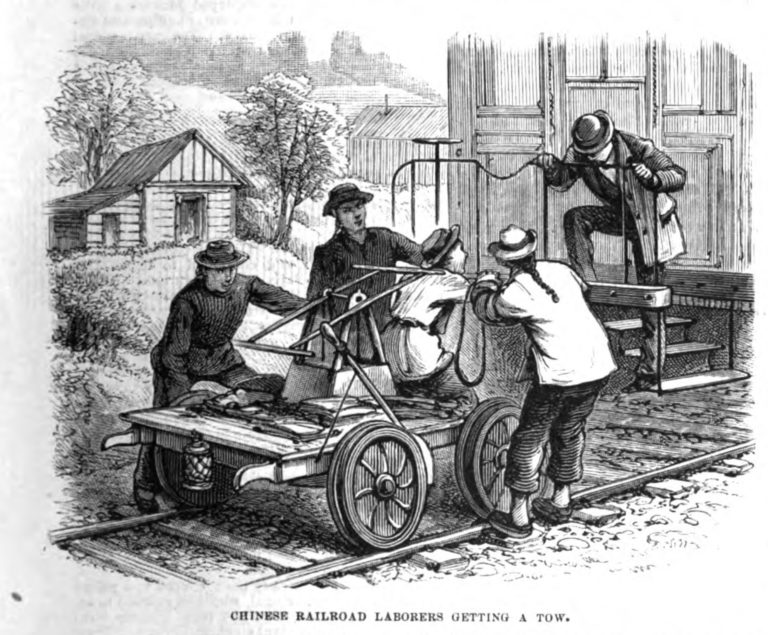

What the distinctive visual treatment of the Chinese suggests is that a racialized sense of industrial superiority is being worked out through the illustrated media. The work of both the “Special Artist” and the reporter in one 1877 illustrated article makes the point (fig. 6). In “Chinese Railroad Laborers Getting a Tow,” a male passenger hauls himself up onto the rear platform of a passenger car so that he may observe four workers attaching their handcart to the back of the train. His action carries some symbolic weight, as the journalist’s supporting comments underscore: “Among the ‘side-scene’ sketches which our artists scratch down by the way, the Chinese road-menders come in . . . [W]e, on the rear platform, find an ever-fresh delight in looking down upon them.”

Taking into account the longer visual record of these workers raises questions about their putative antithetical position to industrial speed. Indeed, the Leslie illustrations obscure an important quality once associated with Chinese labor. That quality was speed.

When the owners of the Central Pacific Railroad took on Chinese workers in 1865 (by 1869 they employed roughly eleven thousand Chinese workers—about 90 percent of their workforce), they gained a fighting chance against the Union Pacific, their rival in competition for track mileage. Prior to bringing on the Chinese, the company lacked sufficient and affordable manpower. Hiring Chinese immigrants filled that labor gap and allowed the railroad to dramatically increase the pace of construction. The Central Pacific was to build eastward from Sacramento while the Union Pacific built westward from along the Missouri River. Gaining track mileage mattered because the first Pacific Railroad Bill passed by Congress in 1862 determined that government bonds would be paid out and land grants assigned per mile of track laid. Further heating up the “race” to lay track was the fact that no officially fixed meeting point for the two lines had been set. Hence, in a situation in which time was both money and space, speed of labor meant increased track mileage laid and greater profits. In the spring of 1866 this was a losing equation for the Central Pacific: the company was still being outpaced by the Union Pacific. Recourse to Chinese workers changed that.

Employing this labor force allowed the Central Pacific to extend track over the Sierra Nevada Mountains far more quickly than the company’s owners had originally thought possible (about seven years faster, according to the estimates of owner James Strobridge). When the railhead moved out onto the Nevada and Utah plains in September of 1868, flat expanses permitted greater lengths of track to be laid down at a highly accelerated pace. Indeed, at this point the race for mileage between the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific became something of a media sensation. And attention soon turned to the Chinese laborers who were pitted against the largely Irish workforce of the Union Pacific. Crews from the two companies “volleyed” back and forth in their efforts to speed construction along greater distances in decreasing amounts of time. First the Union Pacific’s Irish crew laid down six miles of track in a day, only to be topped by the Chinese with seven miles. The Irish rallied with seven and a half miles but were ultimately outdone by the largely Chinese crew of the Central Pacific. In the end, Chinese workers won the competition for covering the greatest distance in the least amount of time by laying down over ten miles of track within a twelve-hour period on August 28, 1869.

“If we found that we were in a hurry for a job of work,” Central Pacific owner Charles Crocker later testified before Congress, “it was better to put on Chinese at once.” Such stiff-jawed praise appears to have held firm among the owners of the railroad company. Leland Stanford concurred, writing as early as 1865, “Without them, it would be impossible to complete the western portion of this great National highway in the time required by the acts of congress.” From the outset of their involvement in the construction project and through its dramatic conclusion at Promontory Point, Utah, Chinese railroad labor was thus valued for speeding the railroad’s construction. This fact is obscured in the “Across the Continent” illustrations.

The transcontinental series featured in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper celebrated the new and immense power of the railroad, which could, in a popular phrase of the era, bring about “the annihilation of space and time.” Illustrations of Chinese labor display a shifted awareness of industrial speed. Formerly valued in Chinese workers by their employers, appreciation of speed was transferred within the two series to the mechanical creation itself. With this transference, speed was annexed—by illustrators, by writers, and by publishers—as a quality of experience associated with traversing the breadth of the nation. It is an ironic twist of fate that the Chinese workers who were a cause of this industrial achievement came to be seen very much as its antithesis.

Further Reading:

For a very precise discussion of several transcontinental series appearing in illustrated periodicals of the late nineteenth century, see the sixth and seventh chapters of Robert Taft, Artists and Illustrators of the Old West, 1850-1900 (New York, 1953). On the topic of western tourism in the era more broadly, see Patricia Nelson Limerick, “Seeing and Being Seen: Tourism and the American West” in Valerie J. Matsumoto and Blake Allmendinger, eds., Over the Edge: Remapping the American West (Berkeley, 2001). Furthermore, there are several studies that comment on the railroad and new configurations of industrialized space in the nineteenth century. Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century (Berkeley, 1977) considers the “panoramic view” of the landscape from the windows of moving train cars. See also, Barbara Young Welke, Recasting American Liberty: Gender, Race, Law and the Railroad Revolution, 1865-1920 (London, 2001). In terms of the labor history behind the building of the transcontinental railroad, see Alexander Saxton’s classic The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Berkeley, 1971). On Chinese railroad workers, see Paul Ong, “The Central Pacific Railroad and Exploitation of Chinese Labor,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 13:2 (Summer 1985). On the racialization of this workforce, see David L. Eng, Racial Castration: Managing Masculinity in Asian America (Durham, N.C., 2001).

Currently, there are a number of especially useful studies of late-nineteenth century-representations of Chinese immigrants. Earliest among these is Stuart Creighton Miller, The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the Chinese, 1785-1882 (Berkeley, 1969). More recently, see John Kuo Wei Tchen, New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776-1882 (Baltimore, 1999); Robert Lee, Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture (Philadelphia, 1999); and Anthony Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley, 2001).

Finally, there are several important studies of Frank Leslie and his publishing empire. Among the earliest of these is Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, 1850-1865 (Cambridge, Mass., 1938). Bud Leslie Gambee’s well-researched dissertation also deserves mention for its treatment of both the publication and the biographical information it offers on Leslie the publisher: “Frank Leslie and his Illustrated Newspaper, 1855-1860: Artistic and Technical Operations of a Pioneer News Weekly in America” (Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1963). On the preeminence of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, in terms of illustrated reporting, see Andrea Pearson, “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly: Innovation and Imitation in Nineteenth-Century American Pictorial Reporting,” Journal of Popular Culture 23:4 (Spring 1990): 81-111. Most recent and most thoroughly researched among these works is Joshua Brown’s study of illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley, 2001).

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Deirdre Murphy received her Ph.D. in American studies from the University of Minnesota. She teaches history in the bachelors’ program of the Culinary Institute of America.